The Pyramids of Egypt were already ancient by the time the Egyptian New Kingdom came into existense. Each had taken thousands of labourers to build, utilising decades of labor time. As tombs go, the Pyramids are hopeless at that task. Thousands of people involved in its construction knew its secrets, and there was simply no way of keeping its location secret, for obvious reasons.

The army of workers also had to be fed, watered, clothed and provided with sanitation and health-care, and their work had to be coordinated not only on the building site but also with mining and transport operations extending throughout the land of Egypt - a truly logistical and organisational nightmare, considering the system available at that early age.

With the New Kingdom though, a new variation came into general usage. Rock-cut tombs became popular and more practical. Their simple entrance could be sealed and hidden, so that only priests and workers would know of their existense. And the number of workers could be kept small and specialized. These workers came to be known as the Servants in the Place of Truth.

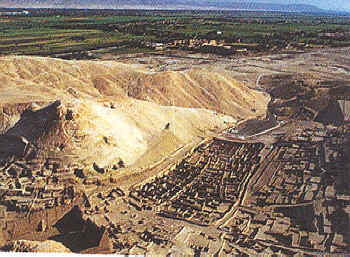

Thus the village of Deir el-Medina was built to accomodate these important class of labourers, who knew the deepest secrets of their Pharaohs, the ones that dealt with their afterlife. Unlike the other Egyptian villages which grew haphazardly along the banks of the Nile, Deir el-Medina was planned by government officials down to the last detail and built way out into the desert, far away from other villages.

It consisted of a tightly-packed camp of small, dark, stone-built terraced houses and completely surrounded by an imposing mud-brick wall. Within would live the Servants in the Place of Truth, and all their wives, children, dependants, servants, pets and livestock. Deir el-Medina would be continuously occupied by the Servants for the next five centuries, except for the two decades they spent building at Amarna for the heretical Pharaoh Akhenaten.

Within the walled village, lived approximately 120 families of maybe 1200 people. Segregated from the general populace, the villagers had to depend on the government for everything; food, clothing, raw materials and even water. Nonetheless the workers had a trump card in their favour, as had been mentioned, and the government took care to see to their every need.

The wall had gateways which were guarded by necropolis officials. Everyone and everything entering and leaving the village was inspected, and those carrying property had to account for it. This was to ensure they were not stealing from the precious burials, or from the government equipment stores, especially of copper tools.

The community of Deir el-Medina was remarkably static and highly literate; even the women could read. Fathers trained their sons to fill vacancies in the work gangs, and as the generations went by, young women in the village tended to marry only the young men of the village.

This was also a village without farming peasants, but consisted of specialized skilled workers, who also provided themselves with elaborate tombs and sold their services to other Egyptians. Many grew wealthy from pay for royal services in addition to funerary projects for affluent Egyptians.

Nonetheless, because of the very nature of living in the village, the families squashed within the walled community spent a great deal of time squabbling over petty stuff and gossiping. The local court, the kenbet, was continually kept busy with accusations of petty thefts, contractual disputes and arguments over wills and property.

Although the literate Servants in the Place of Truth knew themselves to be an elite class of workers, a cut above Egypt's other workmen, nonetheless their work was little different from the daily drudgery of despised workers in the mines or quarries. The cutting of a tomb was hot, dirty and dangerous manual work conducted under difficult conditions.

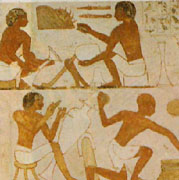

The process was a long established one. First came the religious ceremonies in which a symbolic initial cut would be made using a ritual implement. Then the workers, divided into two gangs to work the left- and right-sides of the tombs, would follow and began digging downwards. Behind them and their basket-men who carried the debris outside would come the skilled workers, the plasterers, draughtsmen, sculptors and painters, who would work on the higher levels as the initial workers excavated the lower levels.

Records showed that absenteeism was common, with workmen providing almost any kind of excuse. Those who did turn up worked eight-day long weeks and stayed in temporary camps close to the tombs. They would have a two-day weekend off, to return to the village.

Thus was how the world-famous rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Queens were made.

The army of workers also had to be fed, watered, clothed and provided with sanitation and health-care, and their work had to be coordinated not only on the building site but also with mining and transport operations extending throughout the land of Egypt - a truly logistical and organisational nightmare, considering the system available at that early age.

With the New Kingdom though, a new variation came into general usage. Rock-cut tombs became popular and more practical. Their simple entrance could be sealed and hidden, so that only priests and workers would know of their existense. And the number of workers could be kept small and specialized. These workers came to be known as the Servants in the Place of Truth.

Thus the village of Deir el-Medina was built to accomodate these important class of labourers, who knew the deepest secrets of their Pharaohs, the ones that dealt with their afterlife. Unlike the other Egyptian villages which grew haphazardly along the banks of the Nile, Deir el-Medina was planned by government officials down to the last detail and built way out into the desert, far away from other villages.

It consisted of a tightly-packed camp of small, dark, stone-built terraced houses and completely surrounded by an imposing mud-brick wall. Within would live the Servants in the Place of Truth, and all their wives, children, dependants, servants, pets and livestock. Deir el-Medina would be continuously occupied by the Servants for the next five centuries, except for the two decades they spent building at Amarna for the heretical Pharaoh Akhenaten.

Within the walled village, lived approximately 120 families of maybe 1200 people. Segregated from the general populace, the villagers had to depend on the government for everything; food, clothing, raw materials and even water. Nonetheless the workers had a trump card in their favour, as had been mentioned, and the government took care to see to their every need.

The wall had gateways which were guarded by necropolis officials. Everyone and everything entering and leaving the village was inspected, and those carrying property had to account for it. This was to ensure they were not stealing from the precious burials, or from the government equipment stores, especially of copper tools.

The community of Deir el-Medina was remarkably static and highly literate; even the women could read. Fathers trained their sons to fill vacancies in the work gangs, and as the generations went by, young women in the village tended to marry only the young men of the village.

This was also a village without farming peasants, but consisted of specialized skilled workers, who also provided themselves with elaborate tombs and sold their services to other Egyptians. Many grew wealthy from pay for royal services in addition to funerary projects for affluent Egyptians.

Nonetheless, because of the very nature of living in the village, the families squashed within the walled community spent a great deal of time squabbling over petty stuff and gossiping. The local court, the kenbet, was continually kept busy with accusations of petty thefts, contractual disputes and arguments over wills and property.

Although the literate Servants in the Place of Truth knew themselves to be an elite class of workers, a cut above Egypt's other workmen, nonetheless their work was little different from the daily drudgery of despised workers in the mines or quarries. The cutting of a tomb was hot, dirty and dangerous manual work conducted under difficult conditions.

The process was a long established one. First came the religious ceremonies in which a symbolic initial cut would be made using a ritual implement. Then the workers, divided into two gangs to work the left- and right-sides of the tombs, would follow and began digging downwards. Behind them and their basket-men who carried the debris outside would come the skilled workers, the plasterers, draughtsmen, sculptors and painters, who would work on the higher levels as the initial workers excavated the lower levels.

Records showed that absenteeism was common, with workmen providing almost any kind of excuse. Those who did turn up worked eight-day long weeks and stayed in temporary camps close to the tombs. They would have a two-day weekend off, to return to the village.

Thus was how the world-famous rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Queens were made.