Sorry for not updating this sooner guys, I've been busy, but now time to resurrect the thread!

The Retro-Innovation of Modern Armor

The slow dissemination of gun and gunpowder technology forever changed the development of armor. No longer would protection from stabs, slashes, and other melee weapons be the priority. Rather, they would need to stop lead balls

1 flying at them at immeasurable

2 speeds. Historians assume that dodging practices were first evolved to deal with this new weapon. Simply moving out of the way has been shown to be effective at least part of the time. Lead balls were notoriously finicky at actually going where one pointed them. However, dodge-ball could only work for so long, and soon historians discovered that anti-dodging devices were used, like firing more guns

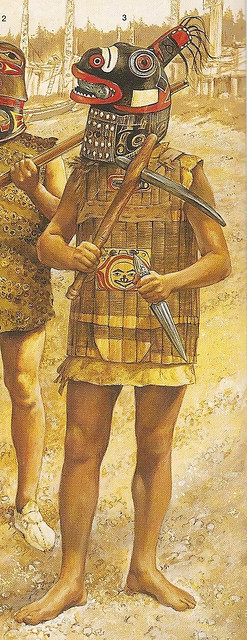

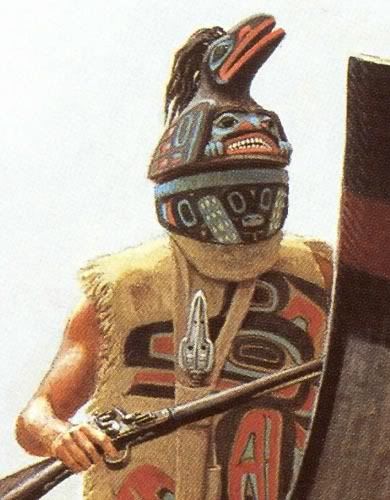

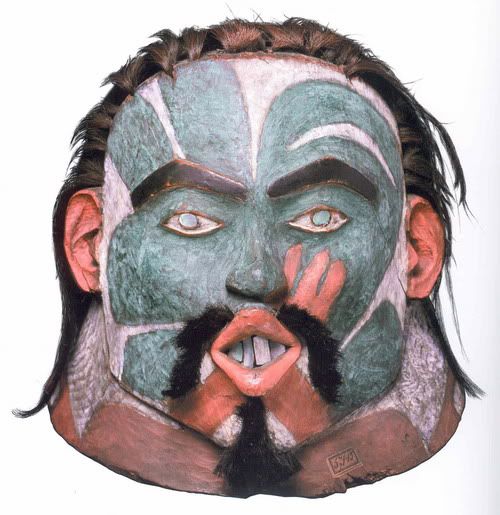

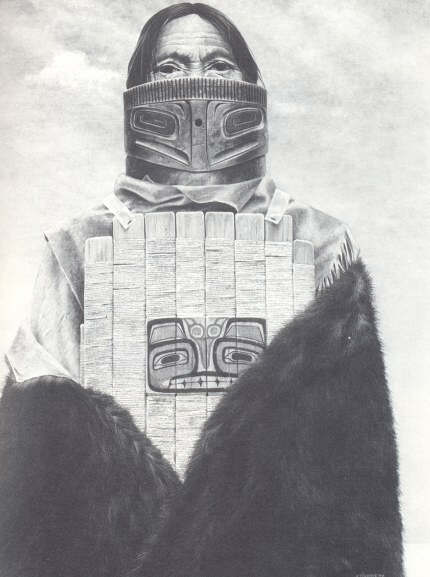

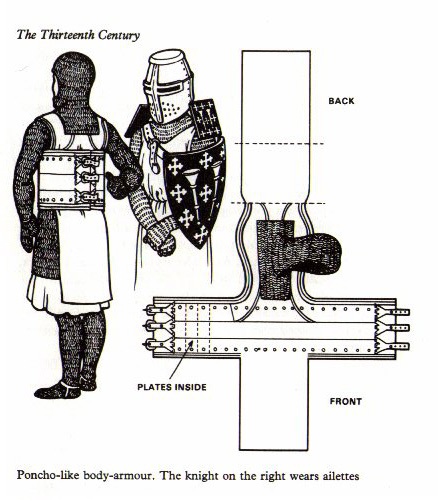

3 at once. Old-Armor declined in usage with the increasing use of the gun,

4 and looked like this once magnificent art-form was lost to the ages.

However, although the records are patchy, historians have a hunch a brilliant man was born somewhere in the greater Europian region.

5 This man is thought to have come with the theory of modern armor, which Dr. Pen of Tration University once summed up as "make armor thicker." Mythology says Europian generals and soldiers alike applauded this man for three days straight after his announcement. Whether or not one could live for three days only applauding is still out for debate.

6

With that, modern armor was born. Even though at this point in history - accurately pinpointed to between the dates of 1456 and 2037 - guns had been refined through rifling and pinpoint bullets, the new thicker armor was almost immune to it.

The trouble was, though, that this new thicker armor was very unwieldy. With current knowledge of humans, the armor we have samples of would have been impossible to carry by oneself alone.

7 Historians, working with archaeologists, have come to the conclusion that the earliest forms of modern armor involved a single armored individual, referred to in sources as a "tank,"

8 carried into battle with the help of three or four "privates."

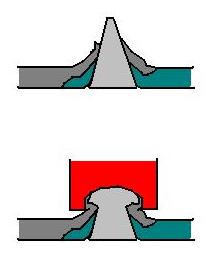

9 He would then be placed on the front-line, and allowed to fire until he ran out of ammo. He would then be removed and relieved. Problems soon arose with these early forms of modern armor, as they were prone to get stuck in mud or trenches.

10 It was assumed, due to the thickness of the modern armor, the soldier was just left to die a horrid death, a bullet to put out him out of his misery would have been deflected right off.

These problems arose at the same time counters were being developed in the "armor race."

11 How does one kill a solider wearing such thick modern armor? Developing bigger guns was the answer. Fragments have been found of rifles astoundingly huge in size, so big as to fit the person in the armor inside! To carry these into battle would have been an amazing sight. Hundreds of privates hauling it on their backs,

12 a large metal man in modern armor just behind them (himself being carried by privates). It is a mystery how the soldiers in modern armor would have picked up or fired such large rifles, the bullets if fit snugly to the barrel would have been almost half their size alone. It could only be assumed that human ingenuity or super-people were used to fire the monstrosities.

The armor race was only to spiral out of control from there. Although records get fuzzy, there are instances of "tanks" being used for centuries after the invention of the modern armored soldier. It can only be assumed that the armor got thicker and thicker, to the point where soldiers would be lost in a maze of metal, firing guns the size of contemporary houses, attempting to penetrate other soldiers in thick armor. No artifacts have been found to make sense of this claim, but considering the early re-development of armor, it is a safe assumption to make.

-

Excerpt from Firearms, Disease, and Metal: A Look into the Short and Brutish Lives of Ancient Humans by April Fools

___________________________

1 Or other "fun" substances

2 It can be measured

3 "I solve practical problems" -

unknown

4 Old-Armor hindered ones ability to run away as fast as possible at the sight of guns

5 Earth used to be divided into very small communities consisting of only tens of millions of individuals

6 Historical records of applause, occurring in moving picture clubs and enclosed athletic domes, at longest last a day

7 Super-people notwithstanding

8 An archaic word used to express ones gratitude

9 Soldier-slaves, well known for their uprisings centuries later

10 Soldiers digging their own graves on the battlefield, called "trenches" in old literature, is a well documented practice

11 Not be confused with arms races, a dangerous activity where ancient people would race upside-down

12 Or rolling it into battle on re-purposed logs, as some historians would argue