The Allegory of the Cave is in the seventh book of The Republic, a work mostly dealing with how to organise an ideal city. And while the very end of the allegory again ties back to how the so-termed Philosopher-rulers of the ideal city must behave towards the less philosophically-englightened citizens (ie by not distancing themselves from them, but instead trying to engage in dialogue about philosophy), the allegory itself is not dependent on any political message.

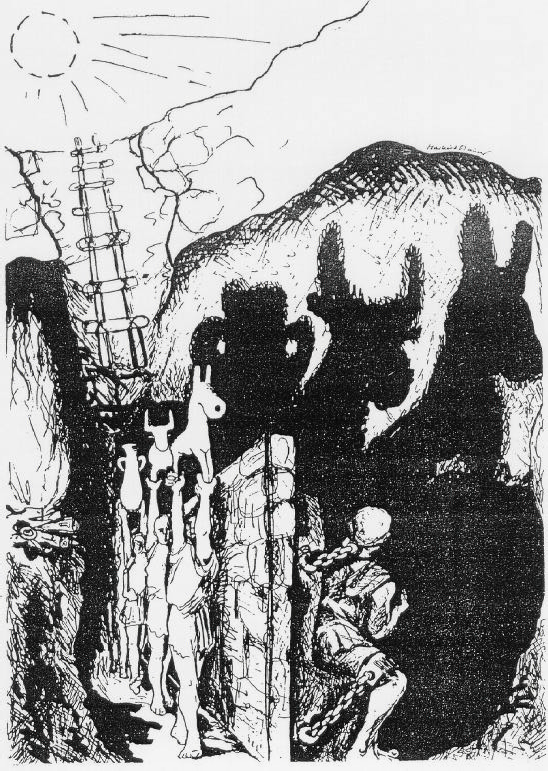

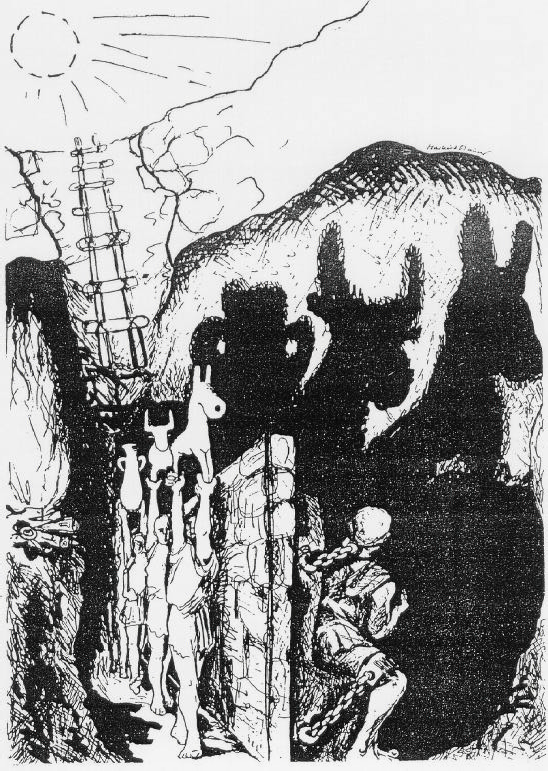

The story of the prisoners in the cave is used so as to cause a more pronounced interest on the ideas of human chains which bound to false objects, so-called phenomena (which literally means 'appearances', juxtaposed to realities). The prisoners in the bottom of the cave are bound in their feet, but also their necks (so as to be unable to move their head and see even the fellow prisoners). They can thus only observe the wall in front of them, and that is filled with moving shadows, due to people carrying idols of objects moving behind the wall a bit above the prisoners, and the fire even further up turning those objects and people into a shadow on the low wall.

Socrates goes on to note that if a prisoner would happen to be freed (it is not mentioned just how this would happen), he would then immediately notice a myriad different points of view even in the first environment he is in, the bottom of the cave. That is due to him now being able to see the wall and the shadows as not something fixed, but as a show of shadows on a plane which can be examined from different positions. This becomes even more prominent when he turns towards the other part of the cave, with the wall and those carrying the objects, and notices the difference being those objects (idols of men and animals or material) and the corresponding shadows on the wall the prisoners only see.

In the end the freed prisoner goes out of the cave, after the fire, and into the world under the powerful light of the sun. At first he cannot see clearly due to the massively more light around, and he also has to just observe the objects (and the sun) as reflections on the surface of the water. The Sun, above, can never be actually examined, but he can know that it is there, which is the final knowledge in the allegory.

* Socrates explains what the allegory meant

Socrates tells Glauco that the prisoners are humans in their state, as those around them. They only bother with phenomena, and try to examine the phenomena, in varying degrees and acuteness, but they are not aware that those are very far removed from an actual 'reality'. The cave generally stands for occupation with the objects available by the senses. The outside (with the Sun above), is the world of mental notions, ideas, archetypes (origin of forms), and finally the over-archetype of the Agathon (it means 'Benevolent'), which is symbolised by the Sun.

*

I thought of starting this thread as a means to discuss this allegory. I decided to use it as the centerpiece in the library seminars for me to more easily (and with a clear central image) compare the views of Plato/Socrates to those of the presocratics, cause the Allegory of the Cave provides a very clear difference between Socrates and the Milesians, Eleans, Abderans, Heraklitan and Pythagorian thought, which was the object of the previous part of this program...

You can discuss the allegory of the cave, its balances, the split between senses and ideas, the thesis that actual knowledge of the truth can happen with humans cause some arche above this system (The Sun/Agathon) enables it, and so on

On the other hand i want to note how much i liked the information found in Diogenes Laertios, a writer of the chronicles of ancient philosophy, according to which some person once noted to another that "I know of what you tell me even less than i know about Plato's Agathon!", to signify just how obscure the latter was as well

The story of the prisoners in the cave is used so as to cause a more pronounced interest on the ideas of human chains which bound to false objects, so-called phenomena (which literally means 'appearances', juxtaposed to realities). The prisoners in the bottom of the cave are bound in their feet, but also their necks (so as to be unable to move their head and see even the fellow prisoners). They can thus only observe the wall in front of them, and that is filled with moving shadows, due to people carrying idols of objects moving behind the wall a bit above the prisoners, and the fire even further up turning those objects and people into a shadow on the low wall.

Socrates goes on to note that if a prisoner would happen to be freed (it is not mentioned just how this would happen), he would then immediately notice a myriad different points of view even in the first environment he is in, the bottom of the cave. That is due to him now being able to see the wall and the shadows as not something fixed, but as a show of shadows on a plane which can be examined from different positions. This becomes even more prominent when he turns towards the other part of the cave, with the wall and those carrying the objects, and notices the difference being those objects (idols of men and animals or material) and the corresponding shadows on the wall the prisoners only see.

In the end the freed prisoner goes out of the cave, after the fire, and into the world under the powerful light of the sun. At first he cannot see clearly due to the massively more light around, and he also has to just observe the objects (and the sun) as reflections on the surface of the water. The Sun, above, can never be actually examined, but he can know that it is there, which is the final knowledge in the allegory.

* Socrates explains what the allegory meant

Socrates tells Glauco that the prisoners are humans in their state, as those around them. They only bother with phenomena, and try to examine the phenomena, in varying degrees and acuteness, but they are not aware that those are very far removed from an actual 'reality'. The cave generally stands for occupation with the objects available by the senses. The outside (with the Sun above), is the world of mental notions, ideas, archetypes (origin of forms), and finally the over-archetype of the Agathon (it means 'Benevolent'), which is symbolised by the Sun.

*

I thought of starting this thread as a means to discuss this allegory. I decided to use it as the centerpiece in the library seminars for me to more easily (and with a clear central image) compare the views of Plato/Socrates to those of the presocratics, cause the Allegory of the Cave provides a very clear difference between Socrates and the Milesians, Eleans, Abderans, Heraklitan and Pythagorian thought, which was the object of the previous part of this program...

You can discuss the allegory of the cave, its balances, the split between senses and ideas, the thesis that actual knowledge of the truth can happen with humans cause some arche above this system (The Sun/Agathon) enables it, and so on

On the other hand i want to note how much i liked the information found in Diogenes Laertios, a writer of the chronicles of ancient philosophy, according to which some person once noted to another that "I know of what you tell me even less than i know about Plato's Agathon!", to signify just how obscure the latter was as well