That’s not true.

A 1990 dollar had the purchasing power of what would now be $1.81, an 81% increase.

In 1990, the lowest quintile of Americans made a mean of $7,166 /yr. In 2014, that quintile made a mean of $11,676/yr, a 62% increase.

1990 second quintile mean of 18,030 versus 2014 of $31,082. A 72% increase.

1990 third, $29,781 v. 2014 $54,041, 81% increase.

1990 fourth, $44,901, 2014, $87,837, 95% increase.

1990 fifth, $87,137, 2014, $194,053, 122% increase.

The threshold income to be in the top 5% of earners in 1990 was $94,748, in 2014 it was $206,568, a 118% increase.

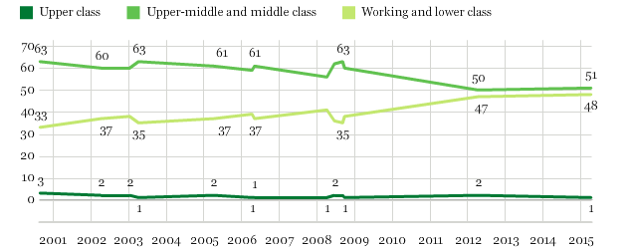

By 2014, about half the country was treading water or making less, relatively, than it was 24 years prior.

Source.