As in other times of disaster, those creatures that fed on death and decay, or on insects (which in turn fed on death and decay), were always the last ones to run out of food. Most of the simpler scavengers and insect-eaters were able to survive in some parts of the planet. The simple, hardy

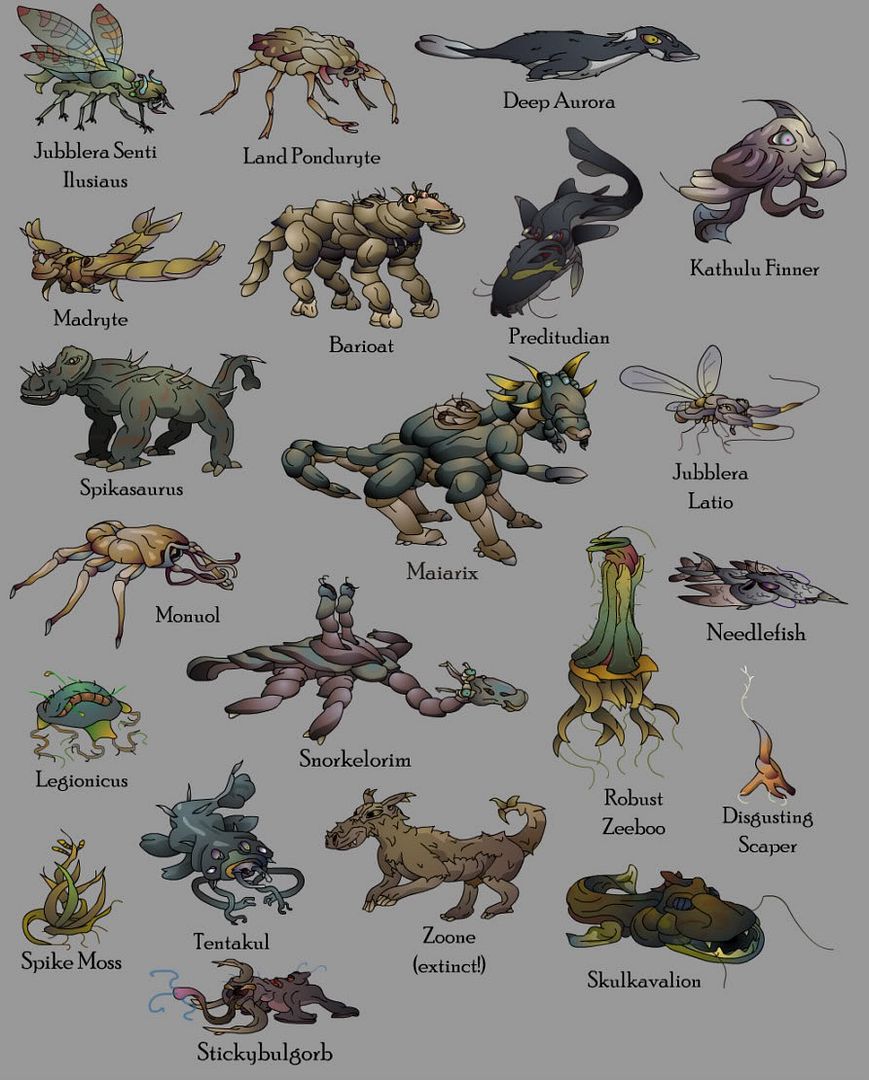

Flannelworms seem to have survived in especially large numbers. The versatile

Land Ponduryte was the latest addition to the land scavengers, and was also lucky enough to be one of the survivors.

As for the insect-eaters, the only main casualty was the

Herbaneraria, the tentacled tree-climbing rival of the

Predatory Inis. Herbanerarias had thrived during the times of lush forest and jungle, but now seemed to lose out to the mostly ground-dwelling Inis. Both species hunted using silk traps (which might not have been 'webs' as such), but it seems the reproductive cycle of the Inis was better suited to the worsening conditions. The

Videobulgorb survived alongside a newly-evolved relative the

Stickybulgorb, which may have lived as a parasite-eater (or just a parasite) on larger animals.

Plant life obviously declined during this time, but diversity had never truly recovered since the last great extinction. With less competition, few species actually went extinct. Although, crucially, some of those that did die off were the larger fruit-producing 'trees', which no longer had resources to grow. The hardy

Liandranel was actually the only real 'tree' left at the end of this era, and it hardly made any fruit at all. The forests that eventually reappeared were much poorer than the old forests and jungles had been, and so there was no big recovery in old forest and jungle dwelling species...

On the other hand, some plants actually did better than before -a landscape of decaying post-uber-tsunami debris, with unreliable sunlight and climate, seems to have worked well for the Zeeboos in particular. The most complex and slow-growing Zeeboos - the

Dome and

Burrowing species - had been largely confined to icy mountainsides since the end of the Snoscapian Era, but were now able to start growing even at the equator, and stubbornly remained there after the climate began to recover. Even older species, the

Tougher Zeeboos and

Rock Zeeboos, also did well - in fact, the Tougher Zeeboos had spawned the even-hardier

Robust Zeeboo by this time, which seems to have been most successful of all. It is possible that, for a few years at least, the only real 'forests' anywhere on the planet would have been large fields of Robust Zeeboos, growing in otherwise barren terrain. Simpler and faster-growing plants eventually began to take over again, led at first by the

Spike Moss, which had evolved from earlier Mosses to be almost as hardy as the Robust Zeeboo, and able to survive in the same dry conditions.

The Legger family, which together made up most of the land herbivores at the start of this era, was reduced to the

ChewOn-Saur,

Spikasaurus,

Tongue Legger and the unique

Mamicalon. The ChewOn was built for toughness, speed and long distance travel, combined with good eyesight and omnivorous diet. Although it didn't have the most efficient digestive organs, it had been one of the most common animals before the disasters began, and small numbers of them were able to survive in all corners of the land. Meanwhile the Spikasaurus, despite its name, was not actually related to the Saur line (the confusion dates back to mistakes made when identifying the first fossil fragments), instead it was descended from the old

Asmara Scraper, a few steps below the

Seer Stalkers which were actually the most sophisticated species of that line. Yet the Seers went extinct, while only the more primitive Spikasaurus that survived. It seems the Spikasaurus had one advantage of its own, in that it laid hardened eggs and had an instinct to guard them against opportunistic predators. Also, although its plant-digesting organs were not as good as the Seer Stalker's had been, they were still more efficient than other types of herbivores, able to gain nourishment from most kinds of plant material...

Unlike other extinction events, this time some large animals were able to survive on land: the

Megaltihavalion and the

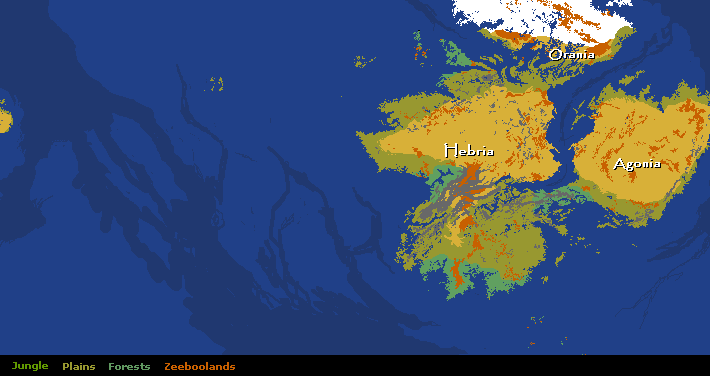

Maiarix. Megalithavalions were able to dig burrows and hibernate during the worst times, while their crushing jaws could bring down just about any animal, and their lazy ambush style of hunting worked well in certain places (lakes, watering holes and river crossings), all of which allowed a small number to survive. The Maiarix survived in even fewer numbers, mostly in the southern plains of 'Hebria' (the western half of the fragmenting supercontinent). Basically it seems the Maiarix was versatile, intelligent, efficient and tough enough to survive the hard times, without being too specialised or demanding. It survived where its relatives the

Velocirix and

Megarix did not (both those species ultimately went extinct).

The Maiarix was not the sole survivor of the Saaranix family, as there were other survivors from the Bariothorim line - the

Barioat was already adapted for life in rugged hills and mountainsides, able to navigate rocky terrain thanks to its strong hooves, and able to take good care of its young and hibernate through cold winters, while the

Snorkelorim was a smaller, stranger, more specialised version of the aquatic

Long-Necked Bariothorim (the Long-Neck itself did not survive).

The biggest animals of all, the impressive

Gigatuplers, would have been tough enough to survive the initial disasters, and their fat-storing bodies would have sustained them for a while. But ultimately they starved to death as they struggled to find enough nourishment to fuel their large bodies. However their smaller relatives, the shy

Stealtuplers, were able to survive. Stealtuplers were already adapted to live in drier conditions than most animals, and shared their desert homes (and possibly shared their own burrows) with poisonous

Toxidids.

High-level predators were always more vulnerable to mass extinctions, due to their position at the top of the food chain. In the immediate aftermath of any disaster, predators could feast on dead, injured, starving or otherwise weakened prey animals, but that wouldn't last long. Even at the start of this era, there was already a lot of competition among a variety of active-hunting predators - various species of Lupivuses, Kaklieas, Gorgaths, and others - while none of the main prey species were easy targets...

By the end of this era, only the

Lupivus Secus and

Ground Kakliea remained from the main predator species. The stealthy

Shadow Kakliea, the poisonous

Valios Toxicum, the mighty

Banded Lupivus and

Dire Lupivus, as well as all of the Gorgaths, and in fact all the descendents of the

Zunatra, all went extinct...

The Lupivus Secus was already an old species, a survivor of several ice ages and other bad times on the planet. While later Lupivus species and other lines of evolution had become stronger and more sophisticated in many ways, none of them had really surpassed the Secus as a fast and efficient hunter on the open plains. It seems the Secus itself came close to extinction, but managed to cling on thanks to its combination of traits - in particular, having just enough investment in physical strength to overpower most prey, as well as just enough social and pack hunting instincts to be able to bring down hard targets like a lone Maiarix, without being so dependent on the group system that individuals couldn't survive on their own when need be.

It may be worth mentioning that the

Eater Gorgath was very nearly one of the survivors, and was certainly the last of the Gorgaths to die out (some claim to have found fossils of the Eater dating from over a million years after the initial disasters). But while the Eater was good at conserving energy, it wasn't great at hunting in the first place - it was strong, but slow, and not well suited to hunting in the vast barren plains (Megalithavalions and

Mortytes had already filled the roles of ambush hunters in other places).

There are also signs that the

Valios Toxicum survived longer than most, but without its ideal habitat of dense forest and jungle, was ultimately out-competed by the Ground Kakleia on the surface.

The

Zoone was the very last of the Zunatra-descended hunters to evolve, and seems to have done well in the short time it had before the extinctions began. Fossils of its skull show a large nasal passages that probably gave it an unparallel sense of smell for a land animal, which would have been very useful for tracking prey across vast barren plains, although it wasn't as fast nor as resistant to the elements as the Secus, which had begun this era with a large established population.

As for the

Ground Kakliea, this had the niche of nocturnal hunter to itself (at least on the ground, and its night vision wasn't especially good). They were also fairly versatile and adaptable (actually the 'brainiest' land animals left alive), and like the Secus, seem to have been lucky enough to have the right mix of traits to be able to survive. By the end of this era they were probably more numerous than the Secus. Most of all, they owed their survival to the

Burrowing Ball, which was probably their main prey.

Burrowing Balls were themselves versatile omnivores, able to eat other small animals and insects, but probably survived by digging into the roots of Zeeboos and other plants. They weren't the most efficient animals, but since they could dig deeper tunnels than most, they were better able to avoid predators and harsh conditions on the surface. Also, their sight and hearing were still about the best of any animal, which was useful - in addition to the Ground Kaklieas, their tunnels would have often been breeched by hunting parties of Mortytes. Still, they survived to become the last living descendents of the first feathered Valions of ancient Agonia, from which the Kunatra, Zunatra and most of the now-extinct predators had also been descended.

The amphibious

LungScraper survived another mass extinction, alongside its more recent descendent the

Proto-Otterus, and also the

Mudtupler, the swamp-dwelling relative of the Seatuplers and Gigatuplers. For one thing, amphibious creatures were better able to survive massive tsunamis caused by the initial impact events, which would have drowned other land animals, and left other sea creatures stranded and helpless. They also had the freedom to move between shallow water habitat and different islands in search of any scraps of food - many new islands were rising and falling during this era, and most were accessible only to fliers and amphibians.