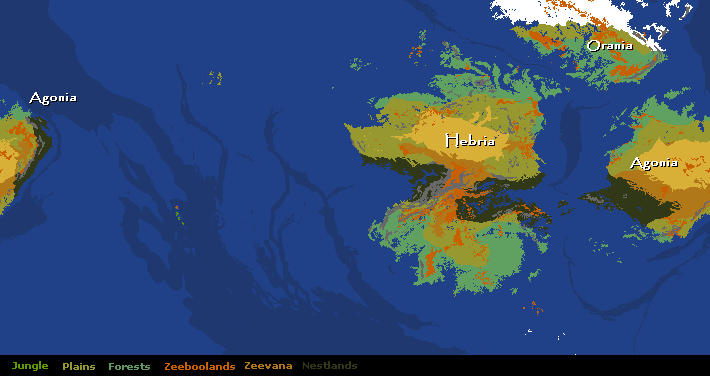

As the continents split further apart, ocean currents changed and stirred up more nutrients from the ocean floor. It is known that volcanic events in the deep ocean caused several population crashes of all kinds of ocean creatures. But the rest of the time, it seems that the amount of plankton was at its highest levels since complex life began. Overall, many species swarmed in huge numbers - especially the surviving Fish species, which provided almost limitless food for predators.

Roxorfish tended to live in coastal water and river systems,

Bathysfish were most common in deeper water and on the sea floor, while the fast

Needlefish were somewhere in the middle and the most multitudinous of all. Some Bathysfish also branched out to become

Tailfish during this era, notable for its elaborate detachable tail, designed to decoy any attackers.

The only large dedicated plankton-eater was the fearsome-looking

Scythus, relative of the Shellsters (of which the

Complexus survived) and

Tarquinia. This species flourished and led to the more sophisticated

Scarthus, which seems to have been even more successful. Vast ‘herds’ of these creatures may have wandered the oceans, with no real predators once fully grown. Remains of the scythe-talons attached to their tentacles are among the most common marine fossils from this era (and were originally thought to be the bodies of a separate species).

While

Preditudians remained the top predators of the ocean, several other kinds of predators flourished. The

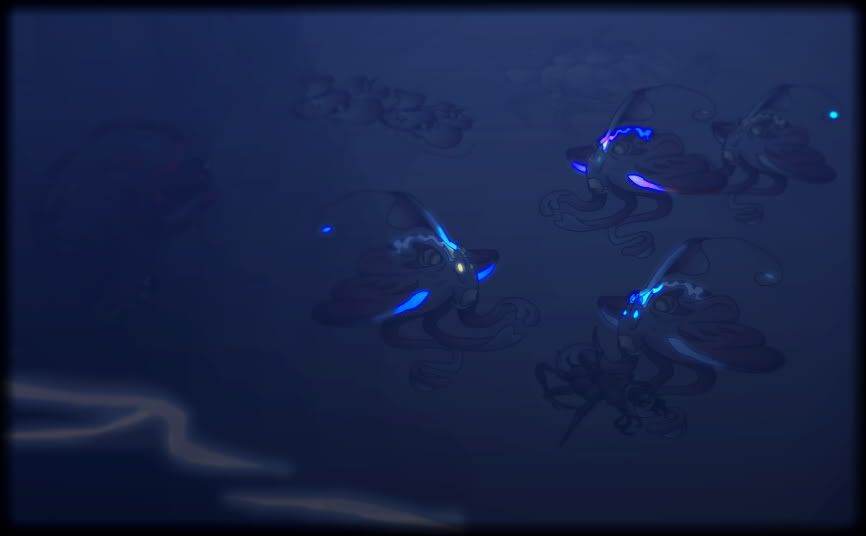

Galorex evolved from the

Phantomorex during this era – this ancient line of predators used changeable skin camouflage and electrical senses to hunt prey, but the Galorex was unusual for the (relatively) sudden appearance of long tentacles in place of its fins. One theory is that these started out as simple display objects, giving potential mates an idea of an individual’s health and strength, and were then exaggerated in size through the generations until they began to be useful for catching prey too. In any case, these creatures became slower but more cunning ambush predators, with a larger brain and sharper fangs to deal with hard-scaled Fish.

Although the

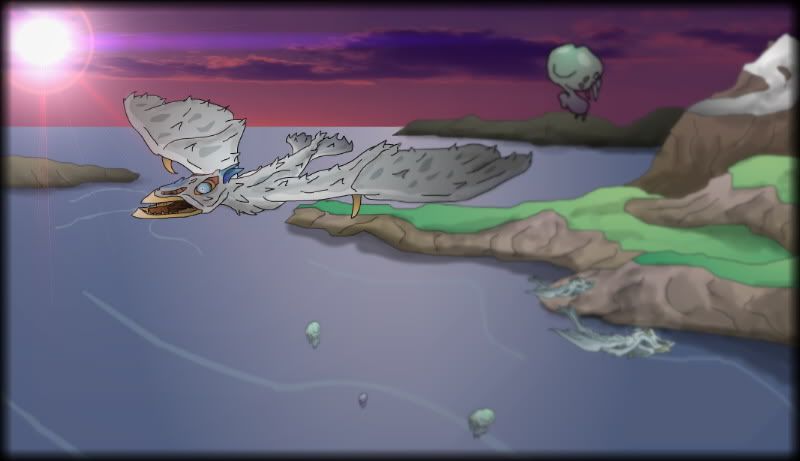

Deep Aurora is considered a borderline member of the Aurora family, the appearance of the

Aquarora is considered as the first in new line of evolution. Unlike their ancestors, Aquaroras were able to give birth and raise their young without hauling onto land (though they still breathed air), and this seemed to give them an advantage over the Deep Auroras (who might face attack from surface predators like the Lupus Argentium, or even the Great Aurora, when they came ashore to breed). Of course, the first Auroras had come from the ocean in the first place, being closely related to the ancestors of Fish species, and they seemed to easily re-adapt to life in the ocean, especially with the benefit of sharp eyesight and good direction-finding instincts inherited from their flying cousins. Aquaroras were certainly fast enough to catch any Fish species of the time, and could even chase down the tentacled Finner species. One mystery is why Aquaroras remained well-adapted for cold temperatures, when polar waters were devoid of any suitable meal-sized animals at this time – perhaps they were nibbling on blooms of

Spongita Snoscapis.

With all the Fish to be had in the oceans, some of the razor-scaled Amphibeels began to lose their ties to land and return to the ocean proper.

Hammerhead Amphibeels first appear at this time, and their strange-shaped heads are thought to have contained basic electrical senses (somewhat similar to the Rex species) and a bigger brain.

Tentakuls also prospered by hunting baby Fish and other tiny animals, especially among plants and rocks where their tentacles could be put to good use. The

Yuckius Sirenis also to be found in great numbers, stalking the boundary of deep water, luring small fish to their doom. In fact the ancient

Shy Hunter seemed to be the only aquatic predator in decline, as it no longer had a monopoly on hunting by vibration senses (Preditudians now had such senses as well as good eyesight) and was outclassed in various other ways.

The excesses of the surface waters were returned to the ocean floor in the shape of corpses, both large and small. Deep ocean scavengers thrived on this, in particular the newly-evolved

Vibravoul, descended from the

Monuol and the venerable

Ponduryte. The Vibravoul was the most sophisticated deep-sea scavenger of the time, and may have been the most numerous, even outnumbering the much-simpler Ponduryte. Large groups of Vibravoul would be seen marching along the ocean floor, following their sensitive scent-organs towards their next carcass. These creatures could also catch small live animals with its tentacles if they got a chance, and were poisonous enough to deter larger predators.

Other deep-water scavengers had mixed fortunes. As

Milipods declined in number on the ocean floor, it seems that some began to specialise in life near the volcanic vents, eventually giving rise to the heat-resistant

Ventopod. This was a relatively simple but successful creature, able to adapt itself to different roles. Although generally a scavenger, it was the only creature able to raid

Bathyfish nests built on the hot vents (apart from other Bathysfish). Being able to swim above the bottom for short distances, it could have avoided brawling groups of Vibravoul and other crawling creatures when it needed to.

The sudden spread of the

Efficient Scaper may have been a reaction to volcanic upset on the deep ocean floor. It is known that several large fissures were torn in the ocean plates as the continents slowly broke up, and these may have regularly spewed out vast amounts of poisonous volcanic sludge and debris, covering over some of the most mineral-rich areas of the deep ocean. At the same time, smaller volcanic vents were probably shorter-lived and more unpredictable. Although animals could simply move on, the slow-growing and mineral-eating ‘plants’ descended from the

Bathyscaper would have regularly lost whole portions of their population. Those adapted for the hot vents, the

Mini Bathystower and

Yellow Bathysplate, seem to have struggled especially (although some suggest that the Mini Bathystower, with its extra heat tolerance, may have colonized giant flooded geothermal caverns beneath the land continents).

Meanwhile the Efficient Scaper prospered - like the older

Disgusting Scaper, it had special chemicals giving it an especially disgusting taste, so it had a better chance to grow and colonize new areas without being nibbled on by animals. But it also seems to have survived, and even thrived in relatively mineral-poor areas where its rivals simply could not. The reason for this is thought to be a whole new range of biochemical tricks evolved by the Efficient Scaper, and possibly a more complex relationship with new kinds of chemeo-synthesising bacteria. In any case, the Efficient Scapers covered large new areas of the ocean floor, providing more sheltered habitat for various small animals of the deep.

Back in shallower waters, the mysterious

Kathulu Habilis Finner appeared, a descendent of the controversial

Kathulu Finner. The only obvious change in body shape was the strengthening of the tentacles, presumably for picking up and manipulating objects on the seabed. But it is believed they also had light-emitting cells on their skin, which either made use of special kinds of bacteria or some other biochemical trick. These cells would give out patterns of light, rather than just reflect it (as with the chromatophores of other animals) - this could be used as a form of communication, even at night or deep underwater, and could potentially send more information than vocal sounds. A group of Habilis Finners signalling to each other may have been one the of the main spectacles on the planet at this time. This ability was probably just beginning to develop, although detailed studies of Habilis skulls have hinted at complex brain structures associated with social behaviour and optical recognition.

As for how the Habilis actually behaved at this time, we only have theories to go on. Relatively-big brains had certainly allowed the older Kathulu species to survive the mass extinction - and whatever they did, the Habilis evidently did better, as its population gradually replaced that of its ancestor. Whether or not the Habilis actually used tools, they probably built complex nests of some kind and hoarded food, although they would still rely on their speed to escape from dangerous predators like the

Preditudian,

Seatupler or even the

Aquarora.

In any case it seems some Kathulu Finners had more success at a simpler life, as they ‘devolved’ into the

Mulu Finner, a more streamlined but less intelligent herbivore, almost as a replacement for the graceful Velocine Finners which had been wiped out earlier. Mulus were just as social as the Habilis, but it is believed they developed a simpler communication system, using their jaws to make rapid clicking sounds to each other.

A new kind of habitat emerged in the tropical waters, based on the

Blisstower. Although descended from the deep-sea Bathyscaper, these ‘plants’ had become better adapted for life near the surface, trapping plankton and making use of sunlight. The Blisstower species added several new tricks - firstly, they gave up on any kind of photosynthesis themselves, but developed a symbiotic relationship with

Legionicus and

Symbicus, allowing their upper surfaces (often poking above the water) to become covered with them. Its likely they harboured other aquatic plants, perhaps various kind of Algae and Urchin, or

Temperate Xeeboos and

Sea Fuzz. These ‘green’ reefs would have provided food and shelter for both swimming and flying creatures. Xeeboos protruding up from the water would have made relatively safe, isolated nest sites for fliers. Even if the more unpleasant and spiky plants dominated below the waterline, some of the hardier creatures (like scaled Fish, Amphibeels and young Amacilndasa) could still make a home there.

However, Blisstowers seem to have had another effect - Legionicus couldn’t control their buoyancy, but could attach to each other. If several Blisstowers grew close together, they could have supported a ‘carpet’ of Legionicus, gaining further support from any large algae or other plants becoming entangled in them. Another symbiotic species, the

Stinglug (related to other Slug species) appeared at this time armed with stinging trendils, and these could have grown underside of the carpets, adding further defence against any nibbling animals. Large carpets of spiky, unpleasant and stinging blobs would have covered the sea surface, blocking out sunlight (making ideal hunting grounds for predators that didn’t rely on vision), and eventually killed off sea plants on the sea floor beneath. Although, the organic debris raining down from above would have encouraged certain kinds of plankton and small scavengers, and the Legionicus would have been regularly broken up by storms and strong winds.

A final twist to the Blisstowers was the appearance of tubular ‘flowers’ as a means of reproduction – these grew above the waterline and relied on flying animals to pollinate them, offering a reward of nectar. The

Frigyte is the most likely candidate for that role, as their appearance in the ocean coincides nicely with the rise of the Blisstowers. It’s likely that some Frigyte sub-species came to rely totally on Blisstower reefs for feeding and breeding sites.

Tarquinia may have been something like mobile versions of the Blisstower reefs, complete with their own animal residents, and may have dragged similar ‘carpets’ with them. These were larger versions of earlier symbiotic creatures, which had become dependent on certain sub-species of Symbicus and Legionicus. Although still classed as animals themselves, with plankton-trapping mouthparts, Tarquinia were otherwise totally passive, spending all their time floating at the surface to get the most sunlight for their attached symbiotes. The evolution of a primitive ‘sail’ structure gave it an energy-free mode of travel, though it probably couldn’t steer itself very well, if at all. Tarquinia may have frequently become entangled in Blisstower reefs, extending the floating carpets of Legionicus even further.

Finally, for whatever reason, there seems to have been little innovation among shallow-sea plants and Spongita species. It could be that older species were still well suited for the situation – among the Spongita species in particular, the

Snoscapis seems to have been thriving like never before in cooler waters, while the

Hypernova seems to have been closely associated with the tropical Blisstower reefs. The

Fan Bubbleo is the only new sea plant species identified from this time, with leaves that could be folded away for safety – likely a response to the swarms of nibbling Fish mouths.

!

!

)

) ). I know there were some earlier but I kinda lost some, plus others weren’t relevant anymore due to things going extinct…

). I know there were some earlier but I kinda lost some, plus others weren’t relevant anymore due to things going extinct…