Chapter Three: First Contact

Remus reached the top of the hill before the rest of the scouting party. His dark brown eyes scanned the horizon. He saw movement on the plain below. A pride of lions were lounging in the shade beneath a lone, broad-branched tree, their tan hides nearly indistinguishable from the dry savannah grasses.

But Remus saw the lions. Julius had praised him, as a boy, for the sharpness of his eyes, and in the intervening years he had trained them to be even sharper. As a grown man, his eyes had probably saved his life, and those of his companions in the scouting party, on more than one occasion.

He scrutinized the pride quickly. There were three males, evident from their luxurious manes, and a dozen females. Two cubs played lazily on the grass. One of the males suddenly raised his head and snarled another male, who snarled back. Then the third male roused himself from his indolent doze, glanced over his shoulder at the other two, and roared a warning. The two malesevidently younger than the thirdslouched submissively and became silent.

Remus smiled in recognition of a familiar pattern. He silently named the two younger lions Remus and Romulus, and the leader, of course, Julius.

The leader of the pride then turned and glanced towards the hill on which Remus stood. He sniffed the air. Remus had been careful to stay downwind of the plain, however, so the lionwhich he knew relied on scent more than sightmade no further moves. For now. Remus would advise the others in his scouting party to be wary; wild animals were unpredictable, and the scouting party was lightly armedequipped for speed, not for battle.

The rest of the scouts came up behind him. Remus glanced over his shoulder at them and pointed to the lions.

Well, Antonius, a stocky young man with close-cropped brown hair and a broad but handsome face, said softly as he followed Remus gaze, I guess we wont be going that way.

Not today, Remus agreed, also speaking quietly. Lions had sharp hearing as well.

Remus turned to his left. At the base of the hill, nearly opposite from where the lions lay dozing, was a grove of trees. He weighed his options. The trees themselves could mask other unseen threats. But they also provided protection. He made his decision.

This way, he said to the party he led, and they moved down the hill and into the trees.

The group moved carefully through the sun-dappled grove. Though they took care to move as quietly as possible, the dried leaves and twigs that littered the ground made that impossible. This was not necessarily a bad thing; many animals would make themselves scarce at the sound of a large party on the move.

They kept moving and noticed that the air became cooler. Soon afterwards, they saw that the trees were dusted with a frosting of snow. They had been moving south and quickly realized that the further they went in that direction, the colder the climate became.

They emerged from the forest into a land unlike any they had encountered thus far. Under their feet, the ground changed from soft plains grasses to barren tundra. Antonius began to wonder if they should turn around, since it was doubtful that a settlement could be founded in such a harsh landscape, and that was the main purpose of their expeditionto find sites for future Roman cities.

Remus stopped suddenly. He held up his hand indicating that the scouting party should do the same.

What

Antonius began to say, but Remus, with a gesture, cut him off.

The scouting party stood, silently listening. A moment later, they detected what Remus sharp ears had heard: rustling leaves and snapping twigs. Something else was moving through a grove of trees to their east, and was coming towards them.

The lions? Antonius whispered anxiously to his leader. His fingers touched the small axe he carried in his belt, seeking reassurance in its sharp obsidian edge.

Remus waited a moment before answering, listening intently. No, he whispered back. Theyre walking on two legs. Theyre human.

Antonius stared at his leader in mild amazement and admiration. How Remus could tell that from sound alone, he had no idea. The rustlings in the forest could have been humans, wolves, bears, or even elephants for all he could tell.

A moment later, Remus was proved right. A group of about a dozen men emerged from behind the leaves and tree trunks directly in front of Remus party. They were dressed in animal skins, but carried heavy clubs, unlike the Roman scouts. Their hair was black and straight, their skin slightly golden, their eyes dark and almond-shaped. They stopped dead in their tracks when they spotted the other group of men. No doubt they were trying to assess, as Remus and his companions were doing, if they faced a threat or not.

It was not the first time Remus had encountered other humans. His group had discovered a few villages in their travels, and had, through Remus diplomacy, managed to win over the locals. They had even bestowed gifts upon them: gold, which was returned to the nascent treasury in Rome, or a map of nearby territory. One tribe near Rome itself had even shared their invaluable knowledge of farming.

But they had never encountered a group clearly scouting territory like themselves before. Nevertheless, Julius, his foresight remarkably clear as always, had prepared Remus for exactly this possibility.

Remus spread his arms wide, his empty hands indicating he offered no threat. A slight but welcoming smile appeared on his lips, and he bowed his head slightly in a gesture of respect.

He raised his head and watched for a reaction. The other men turned towards one of their group, clearly their leader. This man gathered his right hand into a fist. Remus tensed slightly, but gave no outward sign of reaction to this potentially hostile gesture.

The other groups leader then placed his fist in the open palm of his left hand. He bowed forward, then straightened. On his face was an almost exact duplicate of Remus tentative smile.

Remus let out the breath hed been holding, then slowly walked forward and spoke.

***

What do they call themselves again? Julius asked Antonius.

Japanese, Julius, the stocky young man answered. Though he was not the tallest man in Remus scouting party, he compensated for this by being the swiftest. He had thus been chosen to relay news of the encounter back to Julius. It took a while to learn each others languages, but we spent several days together and eventually managed to understand one another well enough. Remus seems to have a talent for it, he added with no small amount of pride in his groups leader.

Julius smiled and nodded. He had been correct, all those years ago, to see such potential in the young man. And Remus thinks theyre different from the small tribes inhabiting the villages youve encountered? he asked Antonius.

He does. They claim to have a permanent settlement, like Rome.

Julius smiled. No one has a permanent settlement like Rome, Antonius, he said with pride. Or at least, in a few years, we will certainly be able to say that with confidence. He glanced out of the door of the thatched hut he inhabited. He could see down the hill to the flat plains and grasslands beside the river. Rome was modest now, but he had plans, great plans

Antonius, sharing his Chiefs pride in their new settlement and nascent civilization, smiled back. Of course, Julius. Nonetheless, there are parallels. They have a growing settlement like ours, they are scouting its surrounding territory, and they have a leader they admire.

Julius smirked briefly at the subtle compliment, but gave it little regard beyond that.

And

Antonius went on, but hesitated.

And

what else? Julius prompted him.

Its just

well, they claimed their leader

Tokugawa, they call him

they say he

What? Julius asked curtly, growing impatient.

They say he was killed, Julius. In a fight with a lion. And then

then he rose from the dead!

Julius watched Antonius carefully. The Romans regarded Julius escape from death as proof that they were a chosen people, destined for greatness. Julius had let them think that; indeed, he had used that belief to his advantage, to further his agenda. He studied the young man standing before him to get an idea how his people would react to this news. That they were not alone. That there would be other civilizations forming. That they may have friends, or rivals, out there in the world.

And most importantly, Julius wondered, how would they react to the news that there were other immortals, like their own leader.

That sounds highly improbable, Julius remarked slyly. Why, Ive never heard of such a thing! Oh no, wait, I have. Antonius smiled and laughed softly, but Julius could see he was still disturbed by the story and its implications.

Julius rose from the plain wooden chair he sat upon and clasped his hands behind his back. He had long thought about how he would handle this inevitable moment, and decided to test his chosen approach on this young man, so typical of his people: strong, proud, and eager, but still lacking the confidence they would need to build a great civilization.

Let us suppose, however, that the story is true, Julius said, still watching Antonius carefully. Suppose there are others in the world like me, immortal. Suppose these other immortals are also leading and guiding their people, to a destiny they believe is theirs alone. What does that mean, then, for

our people, for

our destiny?

Antonius said nothing. He had no answer, and sensed this question was rhetorical as well, and so he remained silent. But he listened to his Chief intently.

Can we not surmise, he continued, that another tribe, settling permanently, led by an immortal, and building a civilization, would serve to make us stronger? That they are here to

urge us on to our destiny, either by assisting us or by challenging us? The meaning, once considered, is obvious. Whether in peace or in conflict, we will measure ourselves against them. And though it may take generations, we will persevere, and prosper, and

triumph.

Julius watched as Antonius drew himself up, his broad shoulders squared, his back straight, his eyes shining now with confidence and pride.

Yes, Julius thought,

the words I chose for this moment will more than sufficefor one man, and for all. This is how I will bring them this news. For though it is the first time, it will not be the last such encounter with a similar tribe and leader.

Julius knew this. He had known it for years. Thanks to the vision. There would be, he knew, other civilizations like Rome, stirring like a new-borne babe now, but growing, stretching out their hands to eagerly grasp the world. And behind them, guiding them, others like himself. Immortals.

Well. Not

completely immortal. They

could be killed, if one knew how, and again, thanks to the vision, Julius knew. He suspected the other immortals would know as well. If their experiences had been similar, they had no doubt been privy to the same vision. They would know the rules of the game. But there was no reason to share these troubling facts with anyone, not yet anyway, and perhaps not ever.

Yes, Julius. Of course! Antonius answered, his voice swelling with renewed pride in his people and their destiny. I look forward to your first meeting with Tokugawa. It will be as if two of the gods had descended from the mountaintop and come to Rome to

Julius interrupted him. Their leader is coming here? To Rome? he asked calmly, but a little archly.

Oh, Antonius said, suddenly embarrassed. Did I forget to mention that?

***

Julius briefly glanced at his clothing. He was wearing his very best cotton tunic, the cloth bleached white as bone by a combination of exposure to the sun and repeated soakings in urine. The dark brown belt about his waist contrasted with the bright purity of the tunic. From the belt hung a daggerceremonial, of course, but one could never be too carefulof bronze, much harder than obsidian, but rare. Copper, the ore from which bronze was forged, seemed more rare than gold. Julius belt also sported a gleaming golden buckle, and the tunic had several carefully-crafted gold motifs arranged upon the breast.

Julius grunted in satisfaction. Yes, he looked very much the Chief of a prosperous tribe on its way to becoming a civilization of note.

You look splendid, a female voice said, agreeing with his silent assessment.

Julius turned and smiled at the voice. Good morning, Ravenna, he said to his step-daughter. And thank you.

She was older now, of course, but still beautiful. She had taken a matea fine young man who was a splendid metal craftsman. He had, in fact, personally made all of the gold items decorating Julius clothing. They had four childrenthree boys and the youngest, a girl who ruled over her older brothers.

Are you nervous, Caesar? she asked him with an impish grin.

Nervous? Julius said gruffly. Of course not. And I wish youd stop calling me that.

Though she was well into her forties now, Ravenna giggled like a young girl.

Shortly after theyd founded Rome, Julius and Sevilla the druid had had a long discussion about the importance of names. They had decided that, along with permanence of place, there should be some permanence of name and, thereby, of family. Thus Julius had decided that all Romans should have two or three names: a

praenomen, or first name for friendly use; a

nomen gentile, their family name; and, where warranted, a third name, a

cognomen which would serve as a descriptor that could refer to some distinguishing trait or achievement of an individual or ancestor.

Julius himself had taken Gaius as his

praenomen and Julius as his

nomen gentile. He had not given himself a

cognomen; Ravenna, however, regarded this as false modesty on her stepfathers part. So she had teasingly dubbed him Caesarwhich meant fine head of hair in their native Latin. Since Julius was partially baldhe regularly combed his thin hair forward to hide the fact, in a rare act of vanityit was an ironic nickname, designed to get under his skin, which it did. The fact that the name had begun to stick made it worse. People had gone from calling him Caesar behind his back to addressing him that way to his face. Gradually, he was coming to accept it, since it seemed to arise out of genuine affection and familiarity rather than any sort of malice.

Come on, you can put on the calm and collected front with Tokugawa and everyone else, but not with me, Ravenna admonished him good-naturedly. This is our first meeting with the leader of another civilization like our own.

Im nervous,

all of Rome is nervousyou should be too!

Which is precisely why I cant allow myself the luxury of that emotion, Julius said. The people need their leader, in this critical moment, to be serene and calm, even if they are not.

Ravenna sighed. He had a point, and she knew that arguing with him got her nowhere.

Just then, a young boy, Julius page, entered the room. Hes here, he said, his blue eyes wide and nervous, a reflection of how the people of Rome were feeling, just as Ravenna had indicated.

Shall we? Julius said to Ravenna, and they stepped outside.

It was a bright, sunny day in early autumn. Julius could hear migratory birds chirping in the trees on the outskirts of their settlement. It had grown remarkably in a few short years, thanks to the plentiful food provided by the nearby rice paddy. There were plans to build a second settlement now on the sea coast to the southwest, where a large deposit of copper ore had been found.

Gone were the thatched huts they had first built; Rome now consisted of more suitably permanent buildings constructed from wood and clay. Some, such as Julius, even had a second storey. And there were streets of inlaid stone, laid out in an orderly grid pattern, kept clean by regular sweeping and washing.

Julius, Ravenna, and a few of the chiefs attendantsand honour guard of three warriors and a few advisorswalked through the street towards Romes central square. Julius nose wrinkled at the stench originating from a chamber pot sitting out on the front step of one house. Sooner or later a slave would come by with a cart, filled with other reeking buckets, and take them far from the settlement for dumping.

We need a better system of some sort to get rid of human waste," Julius remarked. "Suetonius, remember that, he said over his shoulder to one of his advisors, one of several who would do his best to remember all the ideas that Julius came up with every day.

Thats another thing, Julius thought,

we need a better way, a more permanent way, to keep track of everything

But that line of thought would have to wait. They arrived at the town square. Sevilla was already there waiting. The elderly druid had to walk with the assistance of a stick now, and two slaves held a leather canopy above her head to shield her from the sun, but her eyes were as intelligent and lively as ever. Julius and Ravenna smiled at her.

Good day, Caesar, she said in greeting. Was that an impish grin he saw, tugging at the corners of her thin, aged lips, when she used the teasing

cognomen? Julius let it pass with nothing more than a briefly-cocked eyebrow, a nod, and a sidelong glance.

The party came to stand in the middle of the modest town square. Most of Romes citizens were gathered around its fringes, eager to see the foreign dignitary coming to visit their settlement.

Suddenly, the mid-day silence was shattered by a distant male voice coming from down the street, speaking in a foreign tongue, but plainly announcing the arrival of the Japanese leader. Julius could only recognize a few words; he was far too busy to have become fluent in Japanese. But the name

Tokugawa he heard plainly.

It was then that he felt the oddest sensation: it started as a tingling feeling at the base of his neck, then spread, until his whole head and shoulders were tense and thrumming. He did is best not to show any discomfort, but he still winced slightly and gave his head a shake.

From down the street, the Japanese delegation approached. They were dressed in long cloth robes, belted at the waist, and wore sandals on their feet. In their midst was a tall man with a distinguished bearing. His face was lined, his shoulders square, his black hair pulled back into a knot at the back and top of his head. He wore neatly-trimmed moustaches. His dark, intelligent eyes were fixed, as soon as they saw one another, on Julius.

Just then, Caesar saw the Japanese leaders cheek twitch and his eyes narrow, every so slightly, as though he were fighting off something that suddenly pained him.

So he feels it too, Caesar surmised about his immortal counterpart.

Interesting. It seems that sneaking up on one another is not an option

Tokugawa walked forward until he stood only two paces in front of Julius. He formed a fist with his right hand, pressed it into the open palm of his left, and bowed forward. Julius responded by also forming a fist with his right hand, but pressed it, closed fingers and palm inward, over his heart. Then he, too, bowed forward slightly.

<Welcome, Tokugawa, leader of the Japanese people,> Caesar said in carefully-practiced Japanese. Remus had become fluent in the language, and during his brief visits back to Rome from scouting, had coached his leader in its use. <On behalf of the people of Rome, I, Gaius Julius, bid you welcome.>

If Tokugawa was pleased by Julius greeting in his native tongue, he did not show it. His face remained impassive as he responded.

I thank you, Gaius Julius, he said in heavily-accented Latin, for your welcome. The Empire of Japan is pleased to make the acquaintance of its lesser neighbours.

Julius heard someone from behind him draw air through his teeth at the barely-hidden, off-hand insult. But Julius was amused, not angered.

Well, perhaps you should go meet one of them, then, Julius remarked, an amused grin turning the corners of his lips upward.

Empire? he thought. Remus had, from a distance, managed to get a glance at the Japanese settlement of Kyoto; it was no larger nor more impressive than Rome.

Several of the Romans chuckled softly. Tokugawa frowned, then leaned toward one of his attendants, who whispered a translation in his ear. Julius watched a brief smile play upon the mans lips, and something between a laugh and a grunt sounded in his chest. He looked at Julius appraisingly and nodded. Julius gestured towards some chairs, sheltered from the sun by a broad canopy, indicating that they should sit as they talked.

The meeting of the two leaders was tense and frustrating, and not just because of the language barrier. Tokugawa was extremely cautious and refused to entertain any of Julius offers to trade knowledge or resources. Allowing passage to Roman scouts through Japanese lands was also out of the question, even in return for a similar courtesy from Rome. Julius sighed and hoped that not all other leaders would prove as truculent as this one.

The meeting ended soon afterwards, agreeably enough; they exchanged promises of peace, but little else. As he prepared to depart, however, Tokugawa, speaking through his interpreter as he had through most of the meeting, made an interesting remark.

Your people, Julius

do they give much credence to this new creed of Buddhism?

Julius brows rose in honest surprise. I would have to say no, since this is the first I have heard of it. What is it, some new sort of religion?

The Spaniards

one of Tokugawas attendants, eager to please, blurted out before his leader hissed him to silence.

It is nothing, Tokugawa remarked with a dismissive wave of his hand. Mere superstition. I take my leave of you, Gaius Julius of Rome. May the peace last until there are no more foes left to conquer.

With that, and a ceremonial bow identical to the one he had used in greeting, the leader of Japan departed.

Spaniards, Julius thought.

The Japanese are on the south coast, so this other civilization is probably to our north. Ill have to direct Remus explorations in that direction

What an odd remark, Ravenna said when the Japanese delegation was out of earshot. No more foes left to conquer? What did

that mean?

Julius turned to Ravenna, who stared at him enquiringly, hoping for an explanation. It means that we must be careful, he said, loud enough for his voice to carry through the square to all the gathered citizens of Rome. The Japanese clearly want to be left alone, to build their civilization with no hindrance, and no help, from Rome. Very well. We shall appease them, provided they honour a matching bargain. For the people of Rome have a destiny, and we will not be gainsaid, nor fettered, nor hemmed in, not by friend and not by foe. We will strive to live in peace, he concluded, but I fear we must prepare for conflict.

The crowd was silent and anxious. They had not anticipated, during these many years of building their settlement, that they might clash with another civilization. Yet now Julius was warning them of that very possibility.

Romes leader paused for a moment, then smiled reassuringly, like a father seeking to comfort a child. But we have agreed to live in peace with our Japanese neighbours, he assured them. Conflict, if it comes at all, will not occur for many years

generations, even. We have time, my friends, time to grow, and learn, and prosper. Let us focus on that. Let us build Rome for our children, and our childrens children. Let us make Rome a shining beacon for others to follow, that they will seek not to oppose us, but to

join us!

The crowd cheered at that, and Julius nodded and smiled in response. In his heart, however, he knew that conflict would come. It was inevitable. No, these people standing here today would not see it, but he certainly would.

For in the end, as he knew now more than ever before

there could be only one.

Julius forever!

Julius forever!

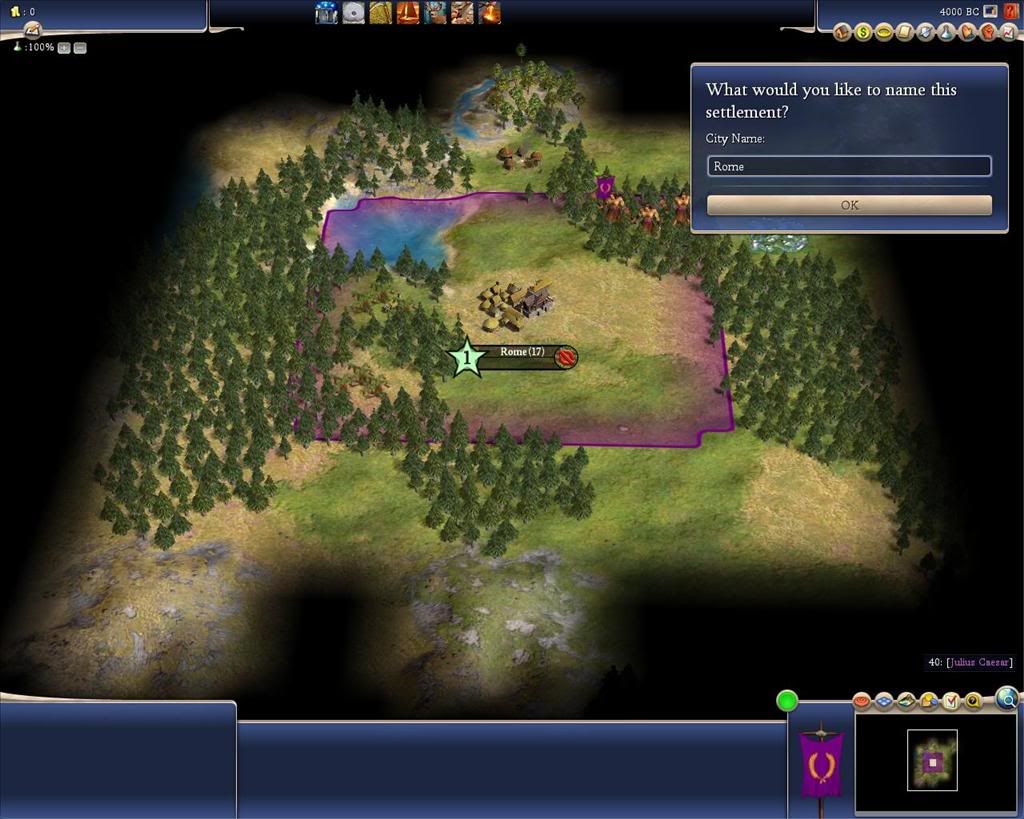

And I'm still just on the first turn!

And I'm still just on the first turn!