Tokugawa paced nervously in the Forbidden Palace throne room in Kyoto. His impulsive elimination of the Spanish was an unforgiveable sin against the Buddha. Isabella was an obnoxious prig, but she was a paragon of the faith until she was dragged into the North African streets and shot by Japanese soldiers.

The pontiff hadn't visited the Apostolic Palace since the invasion. The dedication of the faithful from Seattle to Rome to Kyoto still filled the coffers to overflowing, but in the halls of government, any further appeals to religious unity would ring hollow. No, he had tipped his hand, and now he had to play it.

The first to fall would have to be Rome. Since ancient times, Caesar had thumbed his nose at the papacy, conducting brushfire wars and defying doctrine even under the very nose of Madrid. Now, though, Rome hid behind a facade of piety, refusing to listen to reason or threats from the "infidel" Japanese.

Thankfully, the blood had hardly dried from the boots of the soldiers that had "pacified" Spain, and Bombers and Ninja-Class Paratroopers were secretly stationed in Paris and along Egypt's coast:

The Roman outpost of Cumae fell quickly. Historians still argue as to its final fate. The Japanese party line is that the entire population was executed, down to the last child. There is some evidence, though, that a small group of survivors fled to Rome to make a final stand there.

Rome itself, though, fared little better:

Civilians cowered in the ancient Pyramids (a legacy of the ancient, pagan past) while Japanese Bombers raked the skies with impunity.

When the populace finally emerged, they were quickly rounded up and reeducated in the Japanese ways of "total Buddhism," in which material things such as means of production are not only seen as illusory, but rejected in total and turned over to the state:

As local farmers were counted and registered for the Japanese census, greedy German merchants swooped down and claimed Rome's northern fields as their own. Thousands starved.

In the midst of the dieout, rumors spread that Antium, the fortress-city on the southern tip of the Roman peninsula, had also fallen, and that Julius Caesar had been shipped to Kyoto in chains.

Alexander of Greece, erstwhile Vassal of Russia and longtime enemy of Japan, received reports of the fall of Rome with quiet resignation. He spent his days inspecting his troops on the Athenian parade grounds and his nights staring at maps, looking for strongpoints that he could use to hold off the inevitable.

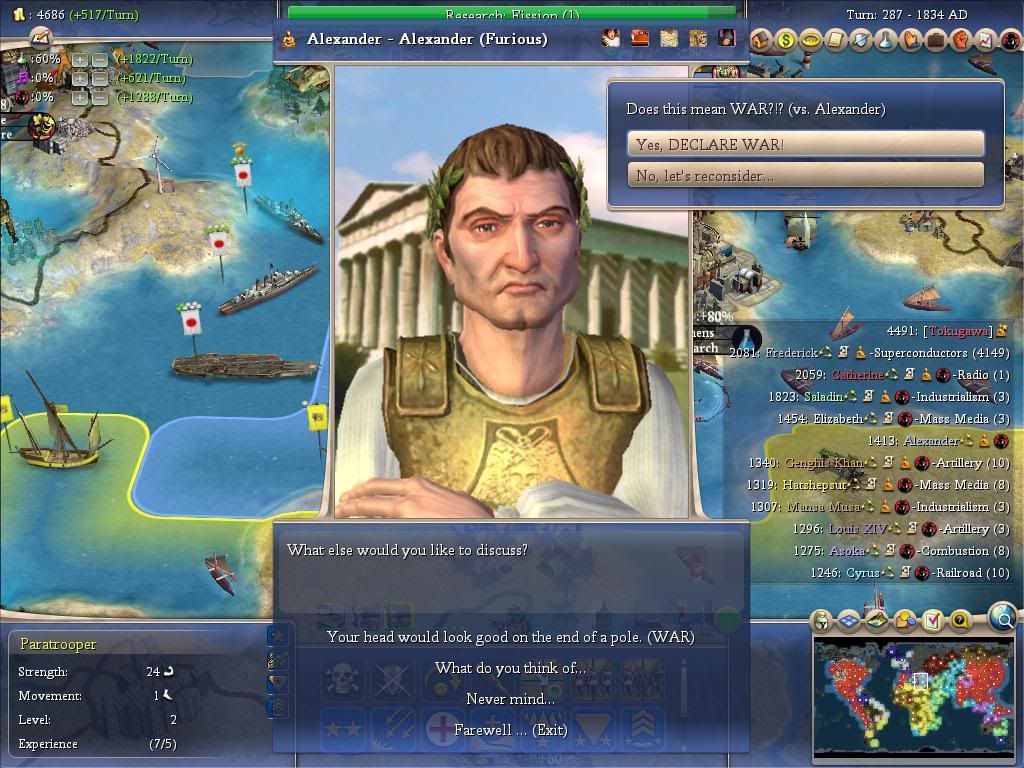

When the Japanese messenger finally came in 1834, backed by a fleet of Destroyers, Transports, and Aircraft Carriers, Alexander received the news of his doom wearily, but utterly without surprise:

Athens fell quickly, as did Sparta. The King of Greece caught carriage after carriage east, constantly staying one step ahead of the conquest-minded Japanese.

In 1840, as Alexander holed up in his final stronghold on the Isthmus of Turkey, he realized he had played directly into Tokugawa's scheming hands. For years, Japanese tanks had been quietly shipped to Persia's western borders. Now they showed themselves, executing a perfect pincer attack. Greece was no more:

Eyewitness accounts state that Alexander died in the fighting.

Tokugawa sipped his Spanish wine and stared down at the Sea of Japan from the window of his private plane. All of these minor wars, of course, were little more than warm-ups for the conflict with Russia. His advisors, of course, were cowards, all, recommending a quick, easy war to subdue Catherine and make Russia a slave-nation of the Empire.

Tokugawa's eyes narrowed. Catherine had, in the Iberian War, taken the Persian city of Sardis and attempted to open another front. She and Cyrus could never coexist peacefully. Besides, the arrogance of her attack was a personal affront to Tokugawa. After all, he was the resident of the Apostolic Palace, and he had taken Cyrus personally under his wing. Such an insult could not go unpunished.

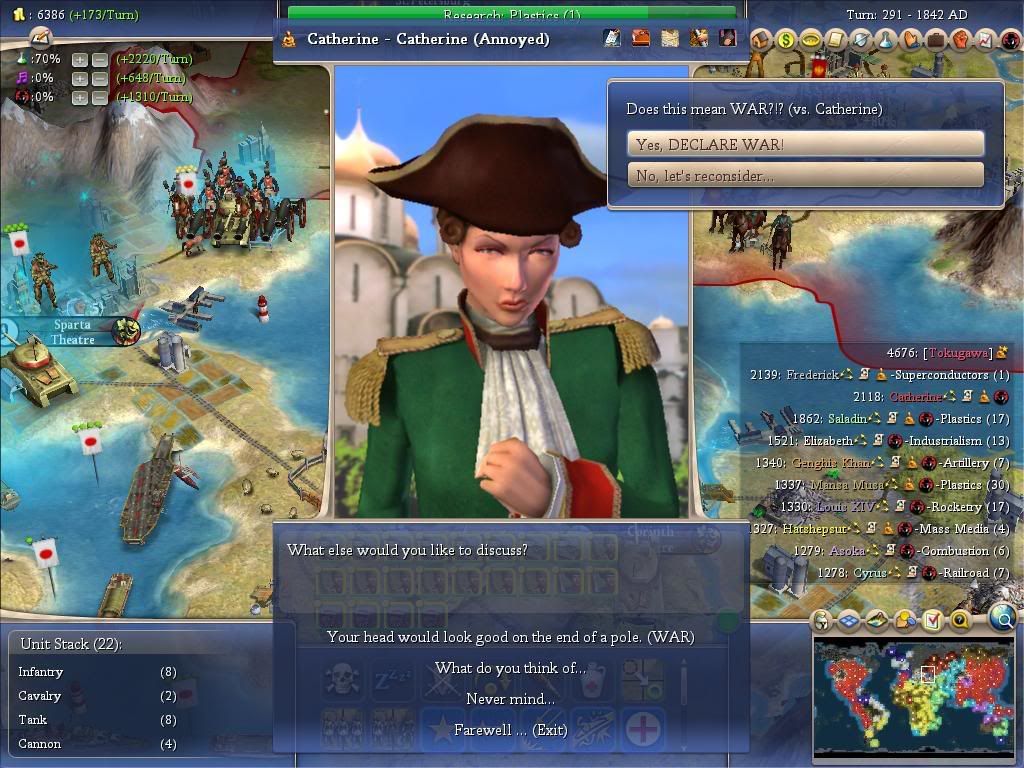

The pampered Russian princess, still drunk from her success in the previous war, welcomed a renewal of hostilities:

"Sir! Mr. President!" A young man with close-cropped hair and the unmistakable features of Mongol descent caught up with Tokugawa in the gardens of the capital building in Tokyo.

"You will refer to me as 'Your Holiness,'" Tokugawa snapped. The title had ceased to have any real meaning on the world stage, but to have it ignored by some minor palace functionary was inexcusable. He made a note of the aide's name tag.

"M-m-m-my apologies, Your Holiness. I come from New Sarai." New Sarai, once a collection of rude huts filled with savages that owed their allegiance to Genghis Khan, was now a modern Factory-City of the Japanese Empire, churning out the weapons and troops that had brought the world to its knees. "I was told to give you this report." A small folder filled with dry prose and photographs. "We have put a man on the moon!"

Tokugawa raised an eyebrow in half-interest. "Does this project have... military applications?"

"Well, not immediately, no, but... Imagine the philosophical implications! The-"

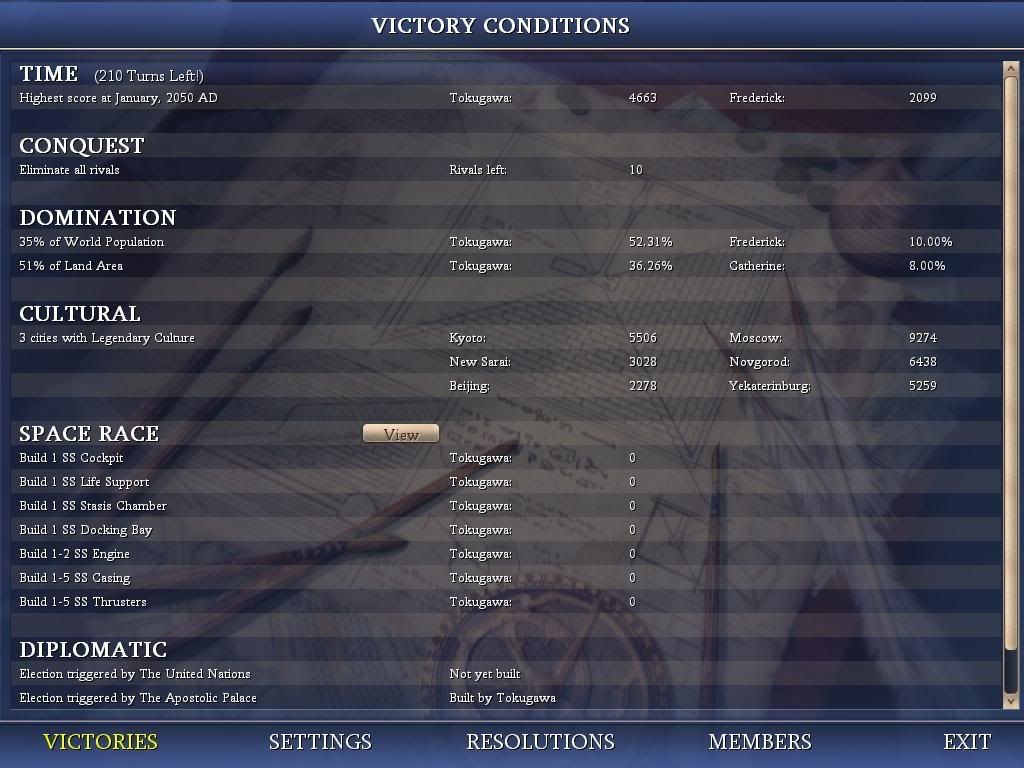

"Then I am not interested. Discontinue all funding to the Space Program. I cannot turn to another world while this one continues to vex me so."

The war against Russia was protracted and brutal. Tokugawa monitored its progress with great interest. Moscow fell in 1850:

Looking over the reports of the wondrous buildings that lined Moscow's streets, Tokugawa allowed himself a small smile. "There is nothing that you can build, Catherine, that I cannot take away."

At the same time, Russian control over Sardis came to an end:

In 1858, the fearsome Russian empire was reduced to the besieged frontier town of Gepid. Gepid lacked adequate food, potable water, even plumbing or electricity. Rumor has it that, trapped and alone, Catherine took her own life as Japanese troops, led by the venerable General Vercingetorix, marched down Gepid's streets:

To the south, war against Catherine's vassal, Mansa Musa, was much more languid. Under constant assault by the unrelenting desert sun, the few tank platoons assigned to the theater made small forays to pillage Malinesian villages and towns, but there was no war of annihilation as there was in the north. Mansa Musa had always treated Tokugawa fairly, after all. A pair of minor cities on Africa's western coast were taken, but the nation of Mali was likely happier to lose them than Japan was to gain them.

Mansa Musa was always a practical man. He had read the reports of Japan's savagery when spurned. At the same time, he knew from his extensive dealings with Egypt that slave-nations were treated fairly. He knew which way the wind was blowing, and decided his future accordingly:

"Sir!"

Frederick turned slowly. He hadn't slept more than 20 hours over the course of the past three weeks. "Yes, Lieutenant?"

"Those Japanese dogs-"

"-have always treated us fairly, Lieutenant. Even during that regrettable episode with Agent Huntzel." Frederick touched the tips of his fingers to his temples, attempting to will away his growing headache. It didn't work. "So I won't have you calling them dogs. Now, what is it about the Japanese that has you so worked up?

"They're amassing their forces outside of Hamburg!"

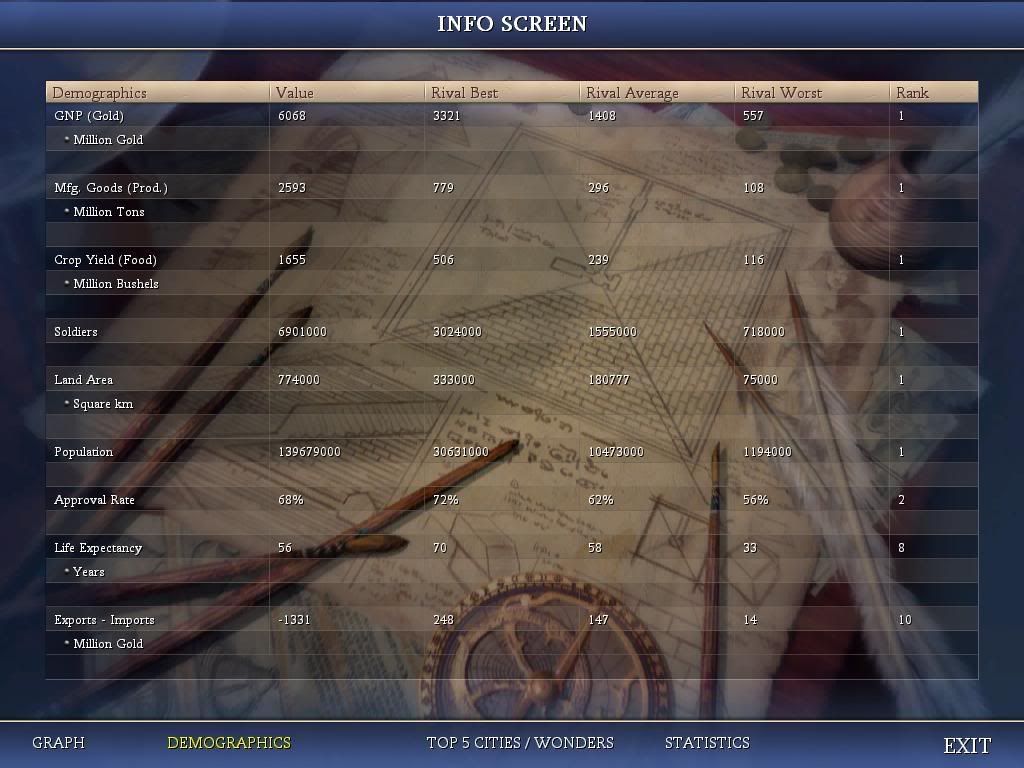

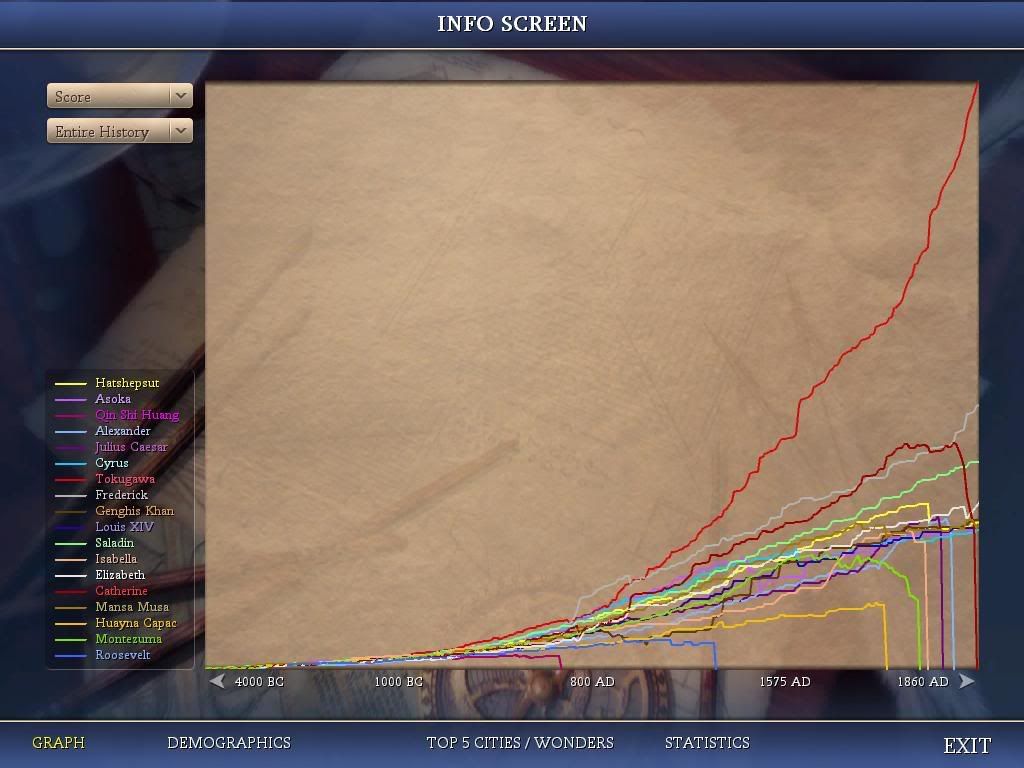

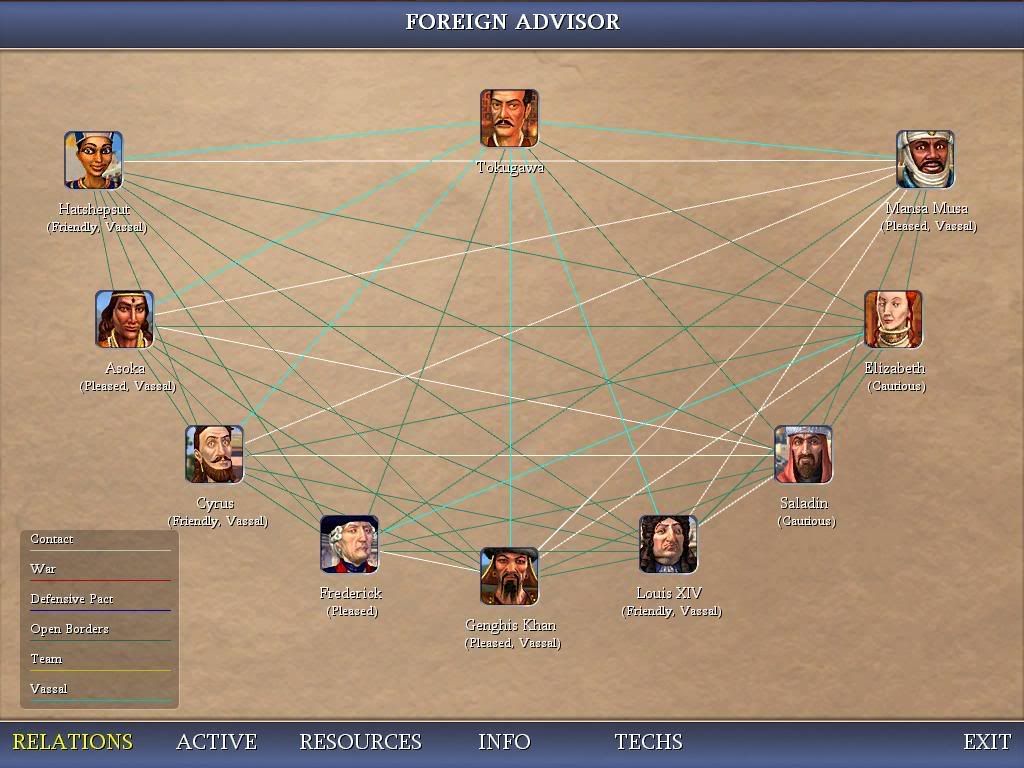

State of the World:

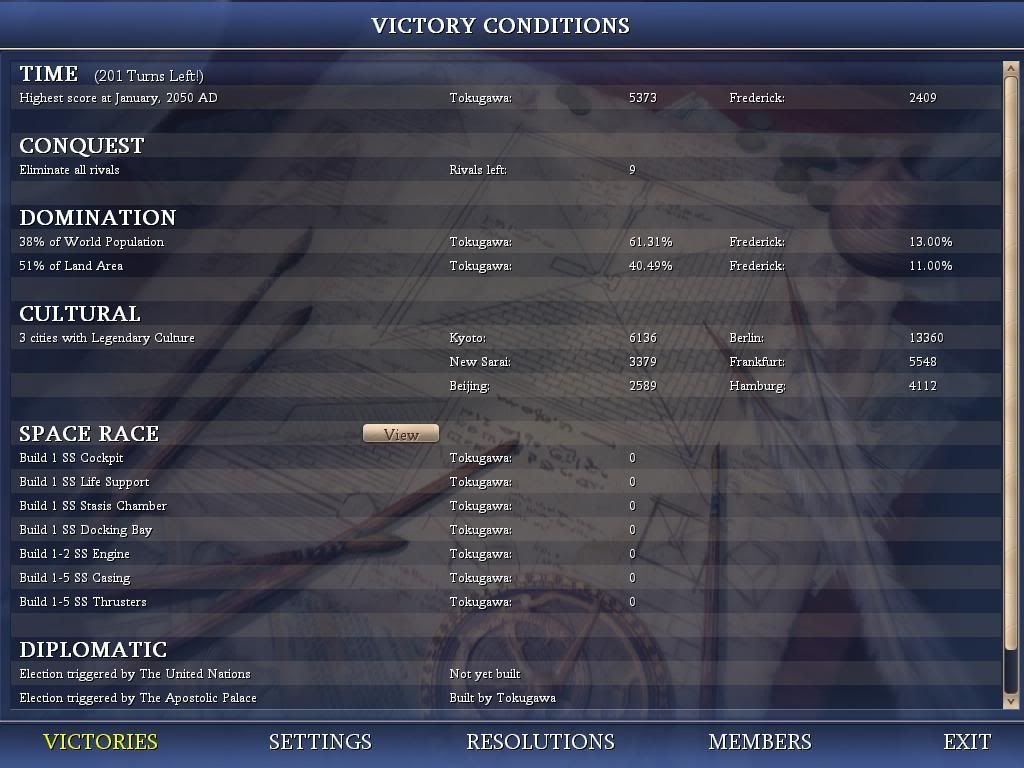

) to a quick and already very bloody conquest win.

) to a quick and already very bloody conquest win.

Probabely a harder game? I heared Honey start isn't that much of a walkover

Probabely a harder game? I heared Honey start isn't that much of a walkover

Probabely a harder game? I heared Honey start isn't that much of a walkover

?

?