Kings of the Atlantic

The Early Period 1787-1876

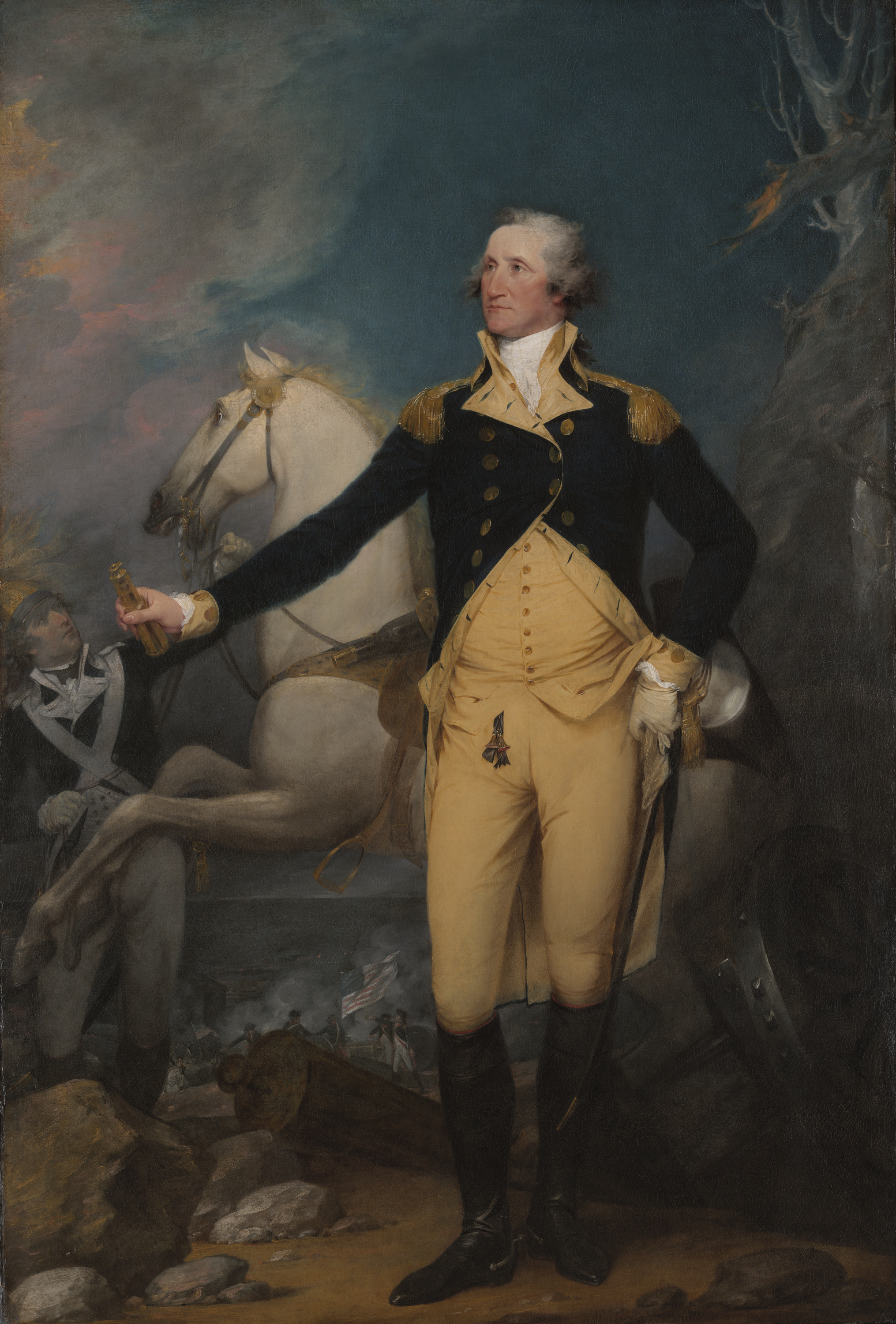

King George I (1787-1797)

Prime Minister(s): Alexander Hamilton, (1787-1797) Monarchist

King George was the founder of the dynasty that would rule this nation. He is considered the Father of His country for His actions. When it became clear that the American colonies could not be ruled by the British, King George became General Washington, and He was put in command of the Continental Army, which, with French aid, was able to secure victory over the British. However, after the war, the delegates squabbled, and many in the Continental Army went unpaid as the squabbles continued. Many of the newly freed nation believed that the nation would be destroyed by internal fighting, and, led by Alexander Hamilton, they turned to General Washington to secure the nation. By the insistence of Hamilton, a new monarchy was created, and they asked George to take the throne. Realizing his country still needed him, George accepted the crown. As his first act as King, Washington had to put down the Albany Confederation that had attempted to defect from the nation. With his victory there, King George began constructing a capital, facilitating the unification of sectional divides, and strengthening the nation. He did institute the Parliament of the United States on the model of Great Britain, and asked Alexander Hamilton to be the nations first Prime Minister , where Hamilton excelled at. Although no direct rebellions occurred during his reign after Albany, many Governors were in contention with King George, and it was difficult to have royal rule completely dominate the country. Although he did not have any children of his own, he selected his step grandson and adopted son, George Washington Parke Curtis to succeed him as King. King George though is consistently well regarded, for he created the Royal Army, Parliament, and gave recognition to the Atlantic Kingdom throughout Europe.

King George II (1797-1857)

Prime Minister(s): Alexander Hamilton, (1797-1816) Monarchist

John Marshall, (1816-1832) Monarchist

John Quincy Adams, (1832-1836) Monarchist

Daniel Webster, (1836-1850) Whig

Samuel Cooper, (1851-1857) Monarchist

The young King George II was not his father, that was very clear. Unlike his father, George II was much for pomp and circumstance, as shown in his coronation in Washington, the first such occasion. However, he was weaker than his father was in leadership, and left many decisions to his Prime Minister, Alexander Hamilton. With Hamiltons aid, in his first few years, the Royal Navy was founded, the banks were centralized. However, that was only the initial moves Hamilton had planned. In 1802, a rebellion in the Carolinas left Hamilton with a unique position. He order the Royal Army in, and captured the governor, declaring him disloyal to the King. With the Royal Army in occupation of the Carolinas, Hamilton reworked the laws governing the states, and installed governors appointed by the King. As the original governors throughout the realm died, resigned, or rebelled, the South Carolina model was followed, and a new Royal Governor was instituted, usually with a new noble title. With revolutionary winds blowing from France, many in the Atlantic Kingdom felt a second rebellion was needed, as their own countrymen began oppressing them under the pretext of noble title. Led by Virginian Thomas Jefferson, the Jeffersonian rebellion of 1804 spread throughout the Kingdom, and using French Louisiana as a base, they began attacking. Hamilton, seeing another opportunity, created an alliance with Britain, and invaded French Louisiana. Though the war was difficult, facing three threats in France, the native Americans and the rebels, help from Britain and the excellent leadership of the Royal Army by General Andrew Jackson, led to the ultimate Royal victory in 1809, cumulating in the Battle of New Orleans, giving General Jackson a noble title. With Jeffersons execution, Hamilton rested easier, and relinquished power to John Marshall, a man of noted skill. Under Marshalls Prime Ministry, the Republican Party was suppressed, and the Crown put even more pressure upon its Governors and its realms. Marshall was quite fearful of another Republican revolution, but when a raid came from Spanish Florida, Marshall and George II ordered Lord Jackson to take Florida, despite Lord Jacksons suspected Republican sympathies. After the Florida crisis, supported by the British, Duke John Quincy Adams declared that the European powers were not to interfere in matters in the Americas, setting the Crowns foreign policy in that regard. However, the Monarchist government of Marshall became unpopular, and the evidence was clear as the more moderate Whig Party began gaining power in both the House of Commons and in the House of Lords. Marshall attempted to save his party be resigning in favor of Duke Adams, but the damage was done; the people and the governors supported the policies of the Whigs. Realizing the nation could not sustain another rebellion at the time, Duke Adams resigned, and recommended to King George II that he ask Lord Daniel Webster to form a new government with the support of the Whigs. Webster accepted, and with his nationalist, protectionist, and modernist views, the nation grew. Roads were improved, and Royal aid went out to businesses as a new wave of industry and factories were hitting the Kingdom. King George II was concerned with how this was changing the balance of the nation, but in the end, he decided to do nothing concerning the policies of his new minister. When Lord Webster died, he appointed General Samuel Cooper as Prime Minister, hoping to bring back more conservative policies. Although as a leader himself, King George II was not nearly as skilled as a father, there are two things that made up for that. The first was his recognition of higher talent in others, allowing his very skilled ministers and nobles run the nations affairs, and the second, was allowing his daughter, Mary Anna Curtis, to succeed him on the throne in order to enthrone a very strong and powerful King.

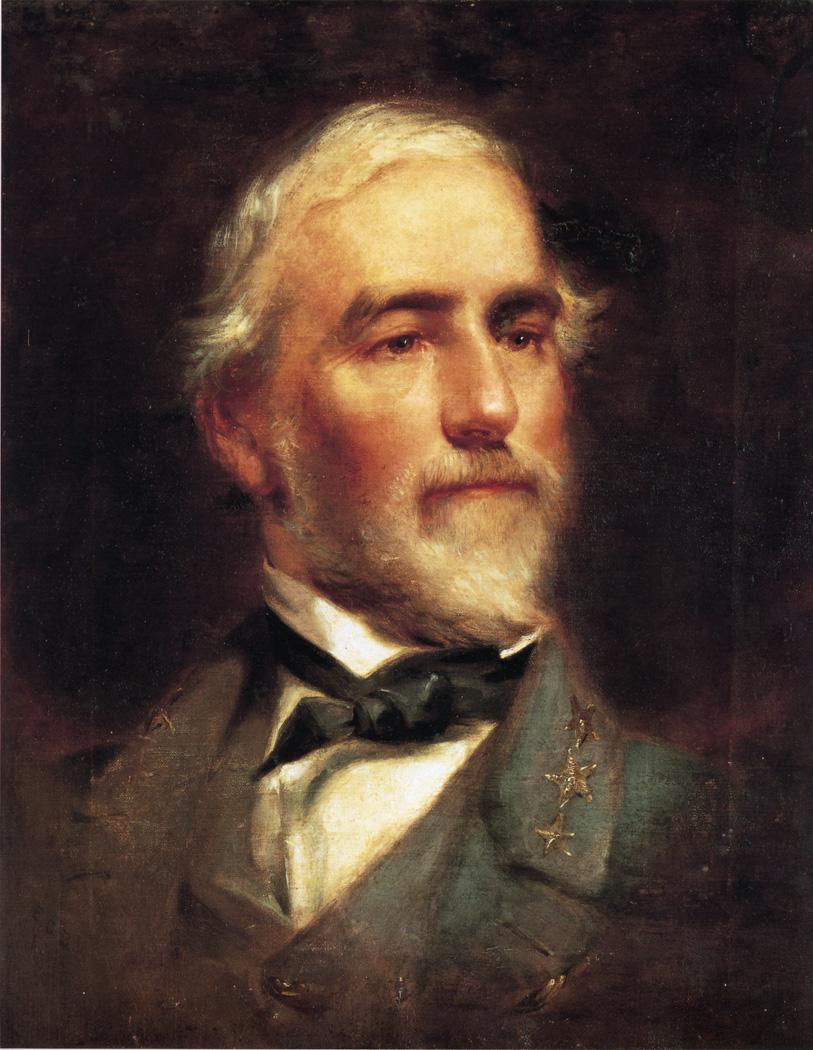

King Robert I and Queen Mary I (1857-1876)

Prime Minister(s): Albert Sidney Johnston (1857-1862) Monarchist

P.G.T. Beauregard (1862-1876) Whig

King Robert and Queen Marys ascension to the throne was well received by many of their commoner subjects, yet many in the nobility feared the new King. They were so used to pushing around the ineffectual King George II, that they feared a loss of their powers were coming. King Robert was heavily concerned with the struggles of the nations economics and their effect on politics. The Whigs policies had helped modernize the nations economy greatly, but many of the new factories were located in the North, owned by wealthy commoners, though Southern Lords were required to still buy many of their industrial goods and textiles from them due to the high tariffs. King Robert tried to show he was with the conservatives by appointing Duke Albert Johnston to the office of Prime Minister, but many lords still feared the winds of change, as evidenced by the renewed growth of the Republican Party. The Southerners were joined by the Northern Lords, who were also supporters of the conservative Monarchist party. Together, they stood in opposition of the New Rich, who owned the factories and the railroads. These fears came to a head during the elections of the early 1860s. In 1860, the realm of Ohio elected a legislature that would give the Republican Party two thirds of the control of the states government. Upon orders from King Robert, the Royal Army moved in and the Ohio legislature was put under Royal control. Under direction of Lee, the Royal Governor created a legislature balanced of the Republicans and the Monarchists, with Lee hoping this would show he still supported the nobility, but was trying to accommodate the new liberal party. It did not work, and the Republican controlled House of Commons had a successful vote of no confidence against Prime Minister Johnston. Although Johnston was saved by the House of Lords, it was clear his political career was over, and King Robert picked a a member of the moderate Whig Party, Sir Pierre Beauregard as the new Prime Minister while Johnston went back into the Royal Army. Under the leadership of Lord Alexander Stevens, the House of Lords agreed to have the Royal Bank of the Atlantic Kingdom block funding for the subsidies for new factories and railroads that would be owned by the upstart commoners, and began considering measures to nationalize some of the factories and railroads. As this scene replayed itself throughout many Northern states where the new rich and Republicans were concentrated, the Republicans had enough, and demanded that King Robert lift his military occupation of the cities of the realm, give back the funding from the Royal Bank, dismantled the House of Lords, and to abandon the nobility, with the taking away of their titles. King Robert flatly refuse, and the Republican Party declared the Kingdom null and void, and that in its place, a true Republic would stand. A true civil war occurred, and though the factories were in the hands of traitors to the crown, the Royal Army remained loyal, and the well trained forces of King Robert crushed the rebellion. After the rebellion though, King Robert knew that the kingdom needed the support of these factory and railroad owners, so he allowed a new system to come into place that would make it possible for a man to work his way into the nobility by merit of his service to the nation, in industry or in military, as many excellent commanders in the Royal Army remained loyal, even though they were commoners. King Robert broke the power of the former Republican party with the inclusion of the new rich on his side, and though they did not become members of the Monarchist party, they all left the Republican Party, joining either the Whigs, or the newly formed Liberal Party. By his own decision, King Robert decided that his nation would need to end their institution of slavery if it would hope to remain a part of the civilized world. He declared in 1865 that all slaves held by the crown would be free by 1870, and that slaves throughout the Kingdom would be free by 1880, and with every slave freed, their former owners would be compensated by the Crown. And although this was per Royal Decree, Sir Beauregard was saddled with most of the blame, and it spelled the end of the Whigs for a time. Beauregard would not survive a vote of no confidence, though King Roberts insistence kept Beauregard in office. The only thing saving the Crown from a second rebellion, this time from the southern nobles, was the heavy military occupation throughout the nation, and the inability to raise a new rebellion so quickly after one had just been fought; no, the nation needed peace for now. King Robert lamented that the rebellion and internal crisis of his reign limited the nations territorial expansion, but under his rule, industry and the railroads flourished due to the greater freedom given to their newly ennobled owners. The Royal Army and the Royal Navy were greatly improved, and as a whole, the Kingdom looked to be on its way to paving a way to greatness.