Ciceronian

Latin Scholar

I'm granting you all the priviledge of viewing the latest essay which I have churned out, this time about the Athenian Empire of the 5th century BC. All dates are given in BC unless otherwise stated. Most citiations from ancient authors are referenced to the place you'll find it in their works. Feedback, comments and constructive criticism warmly welcome. I also hope to add a little list on the sources I used and some recommended reading later. Forgive me if it is a bit long, but I do get carried away writing history essays... There are some pictures though, and a very good map in the second post, if I had added it to the first post it would have stretched the post and made it hard to read. Anyway, here's the essay:

The word imperialism was coined in the 19th century AD – long gone were the days when Athens’ navy had ruled the Aegean, the nations of Europe were now carving up the world amongst themselves. But yet modern historians use this term when referring back to premodern states which followed similar policies, and besides the famous example of Rome we hear also of Athens possessing an empire and following an imperialistic programme. This is both true and misleading. In the 5th century Athens had become the Aegean superpower, and presided over the anti-Persian Delian League, which eventually (apparently through the application of imperialistic aggression) became the Athenian empire. But is an empire not ruled by an emperor, a monarch? Is imperialism (c.f. Latin imperium) not practiced by a geographically large and inherently oppressive state, with a fixed agenda of aggression? The Athenian empire forces us to reconsider these pre- and misconceptions about imperialism, as we shall soon see.

Let us first examine how the Athenian Empire came into existence, for this is vital to our understanding of its purpose and development. A brief sketch then, of the events leading up to its foundation are necessary. The Persian empire, after its rapid expansion in the middle of the 6th century under Cyrus the Great had subjected Lydia, then under the leadership of King Croesus. With this, the Persians practically ruled all of Asia Minor, including the Ionian coast. Their attentions then turned further westwards to the Greeks inhabiting the mainland and the Aegean. In 490, Darius launched an unsuccessful invasion which was repelled by the Athenians at Marathon, and when his son Xerxes came to the throne, he sought to avenge his father’s defeat and in 480 again invaded Greece. After being held up at Thermopylae by a handful of Spartans, the Persians suffered a naval defeat at Salamis and were finally crushed at Plataea and Mykale in 479. But the Persians continued to threaten the Aegean, and so the Greeks, led by Pausanias, the Spartan general, harried them on Cyprus and near Byzantium. However, Pausanias outraged many of the Greeks with his arrogant behaviour, and Thucydides brings to attention that “many accusations of misconduct had been made against him by the Greeks who arrived at Sparta, and his behaviour seemed modelled on the tyrant rather than the general” (1.95.3). In 478 the Greeks brought their concerns before Aristeides, nicknamed “the just” for his fairness and impartiality, and “tried to persuade him to accept the leadership and to take command of the allies who had long wanted to be rid of the Spartiates and to transfer their allegiance to the Athenians”, as Plutarch reports (Aristeides 23.4). The Athenians agreed to their demands and at a meeting on Delos that winter attended by a large number of Aegean and Ionian cities a voluntary league called the Delian League was founded. Its declared purpose was “to take revenge for their losses by devastating the Persian King’s territory”, according to Thucydides (1.96.1). To this end a tribute (phoros) was to be paid annually by all members, either in ships or in gold. The members agreed to be assessed by Aristeides, and the League’s treasury was to be at Delos, where it was supervised by Athenian officials known as the Hellenotamiai, or “treasurers of the Greeks”.

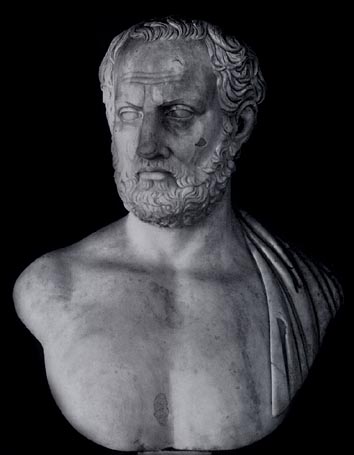

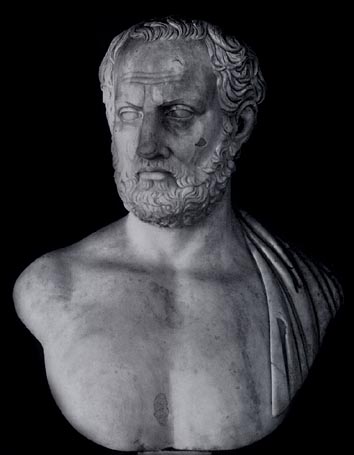

Thucydides, our main source of information for this period, and a reliable one at that

The foundation of the Delian League by the Athenians hardly took place without any second thoughts or ulterior motives; there must have been some awareness of the power such a position would bring with it. It was an opportunistic move at the very least. Herodotus goes even further, attributing intent to the Athenians and complaining that they “made Pausanias’ overweening behaviour an excuse and took away the leadership from the Spartans” (8.3.2). Be that as it may, the Delian League under Athens set about fulfilling its objectives to battle the Persian empire. In 469 there was a major victory against the Persians on the river Eurymedon in Asia Minor, removing the immediate threat which the Persians posed. Some fighting continued until about 450, when it was believed that a peace treaty had been signed by Persia, the so-called “Peace of Kallias”, although its details were already disputed not long afterwards. At this time Athens and its allies were drawn into conflict with Sparta and its allies, the Peloponnesian League, which resulted in a series of drawn-out wars. But during all this time, Athens had steadily been extending its hegemony over the Delian League, and a gradual transformation into an Athenian Empire occurred. Many historians take the transfer of the league treasury from Delos to the Athenian Akropolis as a symbol for this development, but the transformation was far subtler than this.

From the beginning on Athens had taken actions which could leave no doubt as to its dominance over the league. In 475 they were the chief beneficiaries of the capture of the island of Skyros, an action directed not against Persians but pirates, and the island was settled soon after by Athenians. Similar doubts may be raised about the intervention of the Athenians at Karystos on Euboia, which was forced to join the league. It appears that no guidelines had been laid down for the procedure when a city broke its oath of alliance to the league, so when Athens was faced with the secession of Naxos, the island was forced back into the league and had its walls leveled and fleet confiscated. At this time the Persian threat was still very much alive, but when the island of Thasos revolted in 465, the league’s objectives had already been fulfilled. Nevertheless, the Athenians reacted harshly and imposed similar measures as previously on Naxos, the Athenians’ navy and coffers being swelled yet again. The transfer of the treasury from Delos to Athens in 454 can merely be seen as another event in this series. The official reason was that the treasury was in safer keeping at Athens, where the threat from the Persians was not so great. At a point where the Persians were under control and further from taking Delos than they had ever been this seems a ridiculous reason to give. The measure appears all the more self-centered when we consider that a part of the tribute which had been given to build up an efficient navy against Persia was now being used for lavish constructions: “They seemed to be displaying dreadful insolence towards Greece and to be openly acting as tyrants if those who were forced by Athens to contribute to the war saw them gilding and decking out the city like a loose woman, applying expensive stones and statues of gods and temples costing a thousand talents” (Plutarch, Perikles 12.2). In case Athens’ imperialism had until now not been apparent, it now certainly was.

Besides the development of a more forceful imperialism, the Athenian empire underwent other changes, one of which I consider particularly crucial to the way the empire evolved. A tendency took shape for more and more members to pay their tribute in money rather than ships or forces, after initially some members had contributed ships and others money, according to their individual situations (i.e. an inland city or one without a suitable harbour will not have provided ships). Gradually all cities began paying money instead of ships, until only Chios and Lesbos remained, partly for reasons of prestige. Thucydides explains this change as follows: “reluctance to go on campaign led most of them, in order to avoid serving abroad, to have assessments made in money corresponding to the expense of producing ships” (1.99.3). So it seems that the allies were largely content to follow a peaceful agricultural existence in their poleis, rather than become involved in military campaigning. The strong anti-Persian spirit appears to have subsided, mostly because the Persians no longer posed a serious threat to the Aegean and Ionian cities, and so the citizens were not so much compelled to go campaigning as rowers or soldiers as they had been when the Persian threat was very much alive. Whether the tribute was delivered in money or in ships, no economical advantage or disadvantage resulted for Athens, the money now paid being roughly equal to the previous naval contribution. However, the implications were still far-reaching: Athens now controlled a naval monopoly. It now owned almost all the ships at the league’s disposal, since they had built them themselves from the money of the allies. And the Athenians did of course not need to invest all of the money into their navy, but could also construct lavish buildings, as previously discussed. The implications for the allies were also grave: more or less of their own accord they had slipped from the status of nominally equal allies to that of imperial subjects providing money for their hegemon; now truly could one speak of an empire and not merely a league.

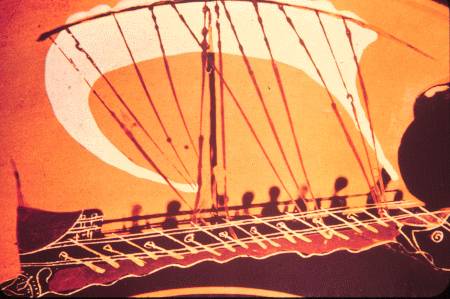

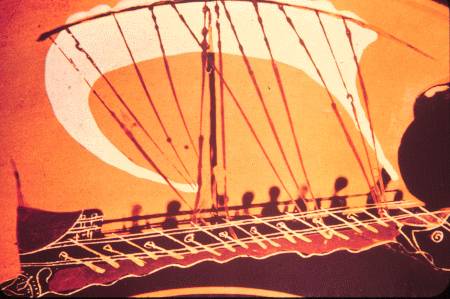

Contemporary representation of a trireme, the prime instrument of power in the Aegean

A further serious complaint often brought against Athens was its brutal interference in its subjects’ independence. The previous examples of Karystos, Naxos and Thasos were only the beginning. Other cities and islands sought for various reasons to secede from the league, either to become neutral or to join the Spartans and their Peloponnesian League. Perhaps the most famous example is the revolt of the cities of Lesbos, except Methyme, and led by Mytilene. After subduing them, the Athenians voted to kill the entire male population, as had been the case on one or two previous occasions, but on the next day they revised their opinion and voted against this measure, resolving instead to kill only the ringleaders. What is called by some fickleness is called by others the magnanimity and courage to admit mistakes. But was interesting to note is that Thucydides reports that when the Lesbians called on the Spartans, the Spartan general Salaethus distributed arms to the citizens, but when they were supposed to charge out at the Athenians besieging the city, they mutinied and refused. It appears that there were rival factions within the city, some pro-Athenian and some pro-Spartan.

So although Thucydides claims that all Greek states hated the arrogance and hegemony of Athens, and “attempted to rebel against them even beyond their ability to do so” these statements seem shortsighted, even false thanks to the evidence that Thucydides himself provides. For Lesbos is not the only example of a divided city: On Rhodes, the oligarchs invited the Spartans to “liberate” them, but upon their arrival the demos or citizenry attempted to flee, but were eventually “persuaded” by the armed Spartan forces to revolt from Athens. Similarly in 416 at Melos large parts of the demos appear to have voiced their dissent at plans to secede from Athens. Why then, if the allies were so infuriated with Athens, did they not accept Spartan intervention more readily? Many offered fierce resistance to Spartan armies, even though their towns were small. During Brasidas’ campaign in Thrace most cities were coerced into surrendering by the sheer numbers of Spartan troops, but when the Spartan general Astyochus attempted to take some Ionian cities opposite Chios, Pteleum, a small town resisted fiercely, as did Clazomenae, another nearby town. These examples should naturally lead us to question Thucydides’ representation of the allies’ grief.

In the politics of 5th century Athens, two distinct systems prevail: oligarchy and democracy. As Aristotle puts it: oligarchy exists “whenever those who own property are masters of the constitution”, whereas democracy is the preferred government “when those who do not possess much property but are poor are the masters.” There is a clear distinction between the oligoi, the few property holders, and the demos, the poorer classes. Democracy in this context is defined by the narrower definition as the rule of the poorer classes over the propertied classes as opposed to the rule of the people as a whole. This is an essential point to make, as it governed the relations of Athenians, their subjects and the Spartans. If cities rebelled from Athenian rule, it was largely because the oligarchic faction had overridden the democratic faction, as evidence goes to show. If then Thucydides, who is one of the most impartial and fair historians of his time, judges that the allies dissented Athenian rule, he is representing the viewpoints of the oligoi, to whom he himself belonged, and to whom he would necessarily have looked for evidence. Democrats where willing to subordinate their desire for the polis’ autonomia (autonomy) and eleutheria (freedom) to their own interests in the class struggle – they had rather the Athenians interfere on their behalf than live autonomously under the rule of the oligarchs, and as shown there is sufficient literary evidence to support this. Therefore the main benefit for the allies lay in the Athenians’ protection of local democracies, and even though their interference in the politics of other states has been described as morally and legally wrong, it was correct in the sense that they were representing the interests of the majority of their allies in a given city. Far from being rejected, the Athenian empire was welcomed by its members as a guarantee for upholding the democracy. The Athenians, on the other hand, drew financial benefits from it which was used to strengthen the military, finance lavish projects and which also improved the situation of the poorer classes in Athens. Isokrates, in his propagandistic Panhellenic Orations nevertheless captured the essence of the main advantage for the allies quite nicely: “They paid us money not to save us but for democracy and their own freedom, and to avoid falling into the enormous troubles they had when they got oligarchies under dekharkies [boards of ten] and the rule of the Spartans.”

It remains to be noted that Athens remained in control of its empire until it was ultimately defeated by Sparta in 404, and lost its hegemony to them, but the Spartans managed their leadership very badly and soon Athens was on the big stage again. The Athenians revived their empire in around 377, and it lasted for about twenty years, but they were never again to regain the glory of the 5th century.

The word imperialism was coined in the 19th century AD – long gone were the days when Athens’ navy had ruled the Aegean, the nations of Europe were now carving up the world amongst themselves. But yet modern historians use this term when referring back to premodern states which followed similar policies, and besides the famous example of Rome we hear also of Athens possessing an empire and following an imperialistic programme. This is both true and misleading. In the 5th century Athens had become the Aegean superpower, and presided over the anti-Persian Delian League, which eventually (apparently through the application of imperialistic aggression) became the Athenian empire. But is an empire not ruled by an emperor, a monarch? Is imperialism (c.f. Latin imperium) not practiced by a geographically large and inherently oppressive state, with a fixed agenda of aggression? The Athenian empire forces us to reconsider these pre- and misconceptions about imperialism, as we shall soon see.

Let us first examine how the Athenian Empire came into existence, for this is vital to our understanding of its purpose and development. A brief sketch then, of the events leading up to its foundation are necessary. The Persian empire, after its rapid expansion in the middle of the 6th century under Cyrus the Great had subjected Lydia, then under the leadership of King Croesus. With this, the Persians practically ruled all of Asia Minor, including the Ionian coast. Their attentions then turned further westwards to the Greeks inhabiting the mainland and the Aegean. In 490, Darius launched an unsuccessful invasion which was repelled by the Athenians at Marathon, and when his son Xerxes came to the throne, he sought to avenge his father’s defeat and in 480 again invaded Greece. After being held up at Thermopylae by a handful of Spartans, the Persians suffered a naval defeat at Salamis and were finally crushed at Plataea and Mykale in 479. But the Persians continued to threaten the Aegean, and so the Greeks, led by Pausanias, the Spartan general, harried them on Cyprus and near Byzantium. However, Pausanias outraged many of the Greeks with his arrogant behaviour, and Thucydides brings to attention that “many accusations of misconduct had been made against him by the Greeks who arrived at Sparta, and his behaviour seemed modelled on the tyrant rather than the general” (1.95.3). In 478 the Greeks brought their concerns before Aristeides, nicknamed “the just” for his fairness and impartiality, and “tried to persuade him to accept the leadership and to take command of the allies who had long wanted to be rid of the Spartiates and to transfer their allegiance to the Athenians”, as Plutarch reports (Aristeides 23.4). The Athenians agreed to their demands and at a meeting on Delos that winter attended by a large number of Aegean and Ionian cities a voluntary league called the Delian League was founded. Its declared purpose was “to take revenge for their losses by devastating the Persian King’s territory”, according to Thucydides (1.96.1). To this end a tribute (phoros) was to be paid annually by all members, either in ships or in gold. The members agreed to be assessed by Aristeides, and the League’s treasury was to be at Delos, where it was supervised by Athenian officials known as the Hellenotamiai, or “treasurers of the Greeks”.

Thucydides, our main source of information for this period, and a reliable one at that

The foundation of the Delian League by the Athenians hardly took place without any second thoughts or ulterior motives; there must have been some awareness of the power such a position would bring with it. It was an opportunistic move at the very least. Herodotus goes even further, attributing intent to the Athenians and complaining that they “made Pausanias’ overweening behaviour an excuse and took away the leadership from the Spartans” (8.3.2). Be that as it may, the Delian League under Athens set about fulfilling its objectives to battle the Persian empire. In 469 there was a major victory against the Persians on the river Eurymedon in Asia Minor, removing the immediate threat which the Persians posed. Some fighting continued until about 450, when it was believed that a peace treaty had been signed by Persia, the so-called “Peace of Kallias”, although its details were already disputed not long afterwards. At this time Athens and its allies were drawn into conflict with Sparta and its allies, the Peloponnesian League, which resulted in a series of drawn-out wars. But during all this time, Athens had steadily been extending its hegemony over the Delian League, and a gradual transformation into an Athenian Empire occurred. Many historians take the transfer of the league treasury from Delos to the Athenian Akropolis as a symbol for this development, but the transformation was far subtler than this.

From the beginning on Athens had taken actions which could leave no doubt as to its dominance over the league. In 475 they were the chief beneficiaries of the capture of the island of Skyros, an action directed not against Persians but pirates, and the island was settled soon after by Athenians. Similar doubts may be raised about the intervention of the Athenians at Karystos on Euboia, which was forced to join the league. It appears that no guidelines had been laid down for the procedure when a city broke its oath of alliance to the league, so when Athens was faced with the secession of Naxos, the island was forced back into the league and had its walls leveled and fleet confiscated. At this time the Persian threat was still very much alive, but when the island of Thasos revolted in 465, the league’s objectives had already been fulfilled. Nevertheless, the Athenians reacted harshly and imposed similar measures as previously on Naxos, the Athenians’ navy and coffers being swelled yet again. The transfer of the treasury from Delos to Athens in 454 can merely be seen as another event in this series. The official reason was that the treasury was in safer keeping at Athens, where the threat from the Persians was not so great. At a point where the Persians were under control and further from taking Delos than they had ever been this seems a ridiculous reason to give. The measure appears all the more self-centered when we consider that a part of the tribute which had been given to build up an efficient navy against Persia was now being used for lavish constructions: “They seemed to be displaying dreadful insolence towards Greece and to be openly acting as tyrants if those who were forced by Athens to contribute to the war saw them gilding and decking out the city like a loose woman, applying expensive stones and statues of gods and temples costing a thousand talents” (Plutarch, Perikles 12.2). In case Athens’ imperialism had until now not been apparent, it now certainly was.

Besides the development of a more forceful imperialism, the Athenian empire underwent other changes, one of which I consider particularly crucial to the way the empire evolved. A tendency took shape for more and more members to pay their tribute in money rather than ships or forces, after initially some members had contributed ships and others money, according to their individual situations (i.e. an inland city or one without a suitable harbour will not have provided ships). Gradually all cities began paying money instead of ships, until only Chios and Lesbos remained, partly for reasons of prestige. Thucydides explains this change as follows: “reluctance to go on campaign led most of them, in order to avoid serving abroad, to have assessments made in money corresponding to the expense of producing ships” (1.99.3). So it seems that the allies were largely content to follow a peaceful agricultural existence in their poleis, rather than become involved in military campaigning. The strong anti-Persian spirit appears to have subsided, mostly because the Persians no longer posed a serious threat to the Aegean and Ionian cities, and so the citizens were not so much compelled to go campaigning as rowers or soldiers as they had been when the Persian threat was very much alive. Whether the tribute was delivered in money or in ships, no economical advantage or disadvantage resulted for Athens, the money now paid being roughly equal to the previous naval contribution. However, the implications were still far-reaching: Athens now controlled a naval monopoly. It now owned almost all the ships at the league’s disposal, since they had built them themselves from the money of the allies. And the Athenians did of course not need to invest all of the money into their navy, but could also construct lavish buildings, as previously discussed. The implications for the allies were also grave: more or less of their own accord they had slipped from the status of nominally equal allies to that of imperial subjects providing money for their hegemon; now truly could one speak of an empire and not merely a league.

Contemporary representation of a trireme, the prime instrument of power in the Aegean

A further serious complaint often brought against Athens was its brutal interference in its subjects’ independence. The previous examples of Karystos, Naxos and Thasos were only the beginning. Other cities and islands sought for various reasons to secede from the league, either to become neutral or to join the Spartans and their Peloponnesian League. Perhaps the most famous example is the revolt of the cities of Lesbos, except Methyme, and led by Mytilene. After subduing them, the Athenians voted to kill the entire male population, as had been the case on one or two previous occasions, but on the next day they revised their opinion and voted against this measure, resolving instead to kill only the ringleaders. What is called by some fickleness is called by others the magnanimity and courage to admit mistakes. But was interesting to note is that Thucydides reports that when the Lesbians called on the Spartans, the Spartan general Salaethus distributed arms to the citizens, but when they were supposed to charge out at the Athenians besieging the city, they mutinied and refused. It appears that there were rival factions within the city, some pro-Athenian and some pro-Spartan.

So although Thucydides claims that all Greek states hated the arrogance and hegemony of Athens, and “attempted to rebel against them even beyond their ability to do so” these statements seem shortsighted, even false thanks to the evidence that Thucydides himself provides. For Lesbos is not the only example of a divided city: On Rhodes, the oligarchs invited the Spartans to “liberate” them, but upon their arrival the demos or citizenry attempted to flee, but were eventually “persuaded” by the armed Spartan forces to revolt from Athens. Similarly in 416 at Melos large parts of the demos appear to have voiced their dissent at plans to secede from Athens. Why then, if the allies were so infuriated with Athens, did they not accept Spartan intervention more readily? Many offered fierce resistance to Spartan armies, even though their towns were small. During Brasidas’ campaign in Thrace most cities were coerced into surrendering by the sheer numbers of Spartan troops, but when the Spartan general Astyochus attempted to take some Ionian cities opposite Chios, Pteleum, a small town resisted fiercely, as did Clazomenae, another nearby town. These examples should naturally lead us to question Thucydides’ representation of the allies’ grief.

In the politics of 5th century Athens, two distinct systems prevail: oligarchy and democracy. As Aristotle puts it: oligarchy exists “whenever those who own property are masters of the constitution”, whereas democracy is the preferred government “when those who do not possess much property but are poor are the masters.” There is a clear distinction between the oligoi, the few property holders, and the demos, the poorer classes. Democracy in this context is defined by the narrower definition as the rule of the poorer classes over the propertied classes as opposed to the rule of the people as a whole. This is an essential point to make, as it governed the relations of Athenians, their subjects and the Spartans. If cities rebelled from Athenian rule, it was largely because the oligarchic faction had overridden the democratic faction, as evidence goes to show. If then Thucydides, who is one of the most impartial and fair historians of his time, judges that the allies dissented Athenian rule, he is representing the viewpoints of the oligoi, to whom he himself belonged, and to whom he would necessarily have looked for evidence. Democrats where willing to subordinate their desire for the polis’ autonomia (autonomy) and eleutheria (freedom) to their own interests in the class struggle – they had rather the Athenians interfere on their behalf than live autonomously under the rule of the oligarchs, and as shown there is sufficient literary evidence to support this. Therefore the main benefit for the allies lay in the Athenians’ protection of local democracies, and even though their interference in the politics of other states has been described as morally and legally wrong, it was correct in the sense that they were representing the interests of the majority of their allies in a given city. Far from being rejected, the Athenian empire was welcomed by its members as a guarantee for upholding the democracy. The Athenians, on the other hand, drew financial benefits from it which was used to strengthen the military, finance lavish projects and which also improved the situation of the poorer classes in Athens. Isokrates, in his propagandistic Panhellenic Orations nevertheless captured the essence of the main advantage for the allies quite nicely: “They paid us money not to save us but for democracy and their own freedom, and to avoid falling into the enormous troubles they had when they got oligarchies under dekharkies [boards of ten] and the rule of the Spartans.”

It remains to be noted that Athens remained in control of its empire until it was ultimately defeated by Sparta in 404, and lost its hegemony to them, but the Spartans managed their leadership very badly and soon Athens was on the big stage again. The Athenians revived their empire in around 377, and it lasted for about twenty years, but they were never again to regain the glory of the 5th century.