At a time, however, when there was no end of making game of and abusing secret societies, I planned to make use of this human foible for a real and worthy goal, for the benefit of people. I wished to do what the heads of the ecclesiastical and secular authorities ought to have done by virtue of their offices

... Adam Weishaupt, 1786

The Illuminati (plural of Latin illuminatus, "enlightened") is a name given to several groups, specifically to the Bavarian Illuminati, an Enlightenment-era secret society. The movement was founded in Ingolstadt (Upper Bavaria) as the Order of the Illuminati, with an initial membership of five, by Jesuit-taught Adam Weishaupt (d. 1830), who was the first lay professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt. The movement was made up of freethinkers as an offshoot of the Enlightenment, and was modeled on the Freemasons.

On 1 May 1776 Weishaupt formed the "Order of Perfectibilists", later renamed "Order of the Illuminati". He adopted the name of "Brother Spartacus" within the order. Though the Order was not egalitarian or democratic, its mission was the abolition of all monarchical governments and state religions in Europe and its colonies.

Weishaupt wrote: "the ends justified the means." The actual character of the society was an elaborate network of spies and counter-spies. Each isolated cell of initiates reported to a superior, whom they did not know, a party structure that was effectively adopted by some later groups.

Weishaupt was initiated into the Masonic Lodge "Theodor zum guten Rath", at Munich in 1777. His project of "illumination, enlightening the understanding by the sun of reason, which will dispel the clouds of superstition and of prejudice" was an unwelcome reform. Soon however he had developed gnostic mysteries of his own, with the goal of "perfecting human nature" through re-education to achieve a communal state with nature, freed of government and organized religion. He began working towards incorporating his system of Illuminism with that of Freemasonry

Writings by Weishaupt that were intercepted in 1784 were interpreted as seditious, and the Society was banned by the government of Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria, in 1784. Weishaupt lost his position at the University of Ingolstadt and fled Bavaria.

The order had its branches in most countries of the European continent; it reportedly had around 2,000 members over the span of ten years. The organization had its attraction for literary men, such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder, and even for the reigning dukes of Gotha and Weimar. Many Illuminati chapters drew membership from existing Masonic lodges. Internal rupture and panic over succession preceded its downfall, which was effected by the Secular Edict made by the Bavarian government in 1785.

After the Edict, some members of the Society established new cells in countries which also had thriving Masonic Lodges. Weishaupt received the assistance of Duke Ernest II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (17451804), and lived in Gotha writing a series of works on illuminism, including A Complete History of the Persecutions of the Illuminati in Bavaria (1785), A Picture of Illuminism (1786), An Apology for the Illuminati (1786), and An Improved System of Illuminism (1787). In France, Illuminati were suspected of deep involvement in the events leading to the French Revolution, and it was not rare to find Weishapt's books among the reading materials of the Jacobins.

When The Eye of Providence, a mystical symbol which was the symbol of the Bavarian Illuminati, derived from the ancient Egyptian Eye of Horus, began to appear in the iconography of the American United States, it was taken as evidence that the Illuminati had adherents among the founders of that country as well. When George Washington was challenged on this point, he at first denied any Illuministic influence in America; he later (as America's first politician) denied that denial, insisting that what he had meant was that the Freemasons (with whom he was closely tied) were not the source of it:

It was not my intention to doubt that, the Doctrines of the Illuminati, and principles of Jacobinism had not spread in the United States. On the contrary, no one is more truly satisfied of this fact than I am. The idea that I meant to convey, was, that I did not believe that the Lodges of Free Masons in this Country had, as Societies, endeavoured to propagate the diabolical tenets of the first, or pernicious principles of the latter (if they are susceptible of separation)..

- George Washington Letter to the Reverend G. W. Snyder (24 October 1798)

Even after having seen first hand the abuses of the Jacobins in the French Revolution, Thomas Jefferson was less critical of the Illuminati, but remained skeptical of their ideology, writing:

Wishaupt [sic] seems to be an enthusiastic Philanthropist. He is among those (as you know the excellent [Richard] Price and [Joseph] Priestley also are) who believe in the indefinite perfectibility of man. He thinks he may in time be rendered so perfect that he will be able to govern himself in every circumstance so as to injure none, to do all the good he can, to leave government no occasion to exercise their powers over him, & of course to render political government useless."

- Thomas Jefferson to Reverend James Madison, January 31, 1800, The Thomas Jefferson Papers

If Illuminism found fertile ground among the new elites in America, it was less successful at reforming or recruiting from the Grand Lodges of England, due to the heavy involvement of aristocracy among their membership.

One of the most notable Illuminati Grand Masters was the Scottish Writer John Galt. Galt was a writer of popular rustic fiction, and had been a friend and biographer of Lord Byron. He was an ardent student of political philosophy, being a friend to the political philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, who established the "Utilitarian" Society, taking the word, as he tells us, from Galt's

Annals of the Parish. Bentham espoused, like the Illuminists, that the purpose of Government was "the greatest happiness of the greatest number" (a formula adopted from Joseph Priestley), and that the pursuit of such happiness is taught by the "utilitarian" philosophy. By this, it might be said that he fathered not one, but two political philosophies which have since, and to the present, been at total war with one another.

When the Grand Lodges became the United Grand Lodge of England with the Duke of Sussex (son of King George III) at it's head, things got hot for the anti-monarchist Illuminists, and Galt went to Gilbralter and established a trading company, ostensibly to circumvent Napoleon, but actually to serve as a critical node in the Illuminati spy network. After his return to England, Galt married Elizabeth Tilloch, daughter of Alexander Tilloch, editor of the

Philosophical Magazine, in which the most important technological breakthroughs of the day were first published. For the next few years, Galt devoted himself to just two duties: writing popular novels and expanding his spy network. This involved constantly moving, and even switching publishers frequently, in order that his motives were not revealed. Galt lived at times in London, Glasgow, Edinburgh and elsewhere, writing fiction and a number of school texts under the pseudonym Reverend T. Clark.

When the authorities again began to close in on his operations, however, Galt was forced to resign his Grand Master's post and again left England, this time going to Ontario, where he founded the city of Guelph in 1827. The town's name was an inside joke from the viewpoint of an Illuminist: it comes from the Italian

Guelfo and the Bavarian-Germanic

Welf. It is a reference to King George IV, monarch at the time of the its founding, whose family was from the House of Hanover, a younger branch of the House of Welf, and

Guelphs being the name given to the northern Italian factions who opposed the reign of the Holy Roman Empire, i.e. medieval Germany, in the 12th to 16th centuries. The community of Galt in Ontario was named after him. His three sons played prominent roles in Canadian politics; one of them, Alexander, was one of the 'Fathers of the Confederation', and Canada's first Minister of Finance.

When Galt returned to Great Britain in 1829 he was immediately imprisoned for several months by authorities, who were unable to find enough proof of his connection with the Illuminati to build a case; the best they could do was trump up a case in debtor's court. It was said that Sir Robert Peel was so frustrated by the inability of the Police to investigate Galt that it led to the establishment of Scotland Yard. In truth, the investigation was hamstrung by the need for secrecy; Galt had so successfully hidden the activities of the Illuminati that it was considered eccentric to even believe in its existence, and Galt's own role was such a closely held secret that the question, "Who is John Galt?" followed by the proper response continued to be the Illuminati's secret password of entrance long after his association with the Society ended.

Galt retired to Greenock in Scotland, publishing his two volume

Autobiography (omitting his association with the Illuminati) in 1833.

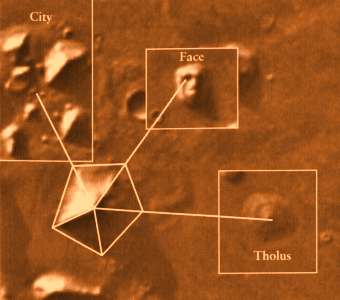

This is our Map. Click on it for a better look.

This is our Map. Click on it for a better look.