Ciceronian

Latin Scholar

Foreword

After the positive feedback for the article I posted here earlier on the outbreak of the Second Punic War, I've decided to post another one of my essays. As some of you may know, I'm now studying Classics at Cambridge, which involves writing an essay a week and lots of language work. Anyway, I just finished an essay on Athenian Democracy which got positive feedback from my prof and from Rambuchan, who got to proofread it before anyone else. So the essay is here, read it if you want to, because I must warn you it is twice as long as the previous essay, counting about 2500 words. So I've added a few pictures to spice it up a bit. All dates in BC unless otherwise stated.

Classical Athenian Democracy - A critical Discussion

The modern term democracy derives from the Ancient Greek word demokratia, which is an amalgamation of the words demos, the people, and kratos, power or sovereignty. For it were the ancient Athenians who pioneered this form of government on a larger scale and gave it its name. However it is important to recognize the differences between our modern concept of democracy and what it meant to the Athenians, and that the two are similar in some aspects but radically different in others.

First of all, the term demos is much more narrow than what we understand by “the people”. In classical Athens the demos excluded women, children under the age of eighteen, slaves and resident foreigners (metics or metoikoi), who had no voting or participation rights. This limited the voting citizen body to a much larger extent than in our modern democracies. In the late 5th century there were around 300 000 people living in Athens, but only 50 000 were allowed to cast votes. We must not forget however, that the exclusion of women and slaves from public matters was commonplace in this time and also long after. Slaves were only freed and given the right to vote in today’s “model” democracy, the United States, in 1865 AD, and women had to wait until 1920 AD to be able to vote. Moreover, the age of eighteen as a boundary for participation is still in use in modern times.

Secondly, Athenian democracy was direct in nature rather than representative as today’s democracies. We elect politicians every few years and let them run the country for us and represent us, rather than getting involved in the process of decision making ourselves. The Athenian democracy, on the other hand, was what we might call a radical democracy, since it interpreted the word democracy very literally or radically to mean the rule of the people in the proper sense, rather than the rule of those few elected by the people. The people would gather in assemblies and vote on matters of importance. These two differences make the Athenian democracy substantially dissimilar to our modern democracy. The first difference limits the participation of the people by opening it only to relatively few; the second increases it through the high level of individual participation and involvement.

To further deepen our understanding of Attic democracy the various different councils should be outlined. The three most important councils were the Areopagus, the boule and the ekklesia. The Areopagus lost importance with the advent of democracy around 500, and continued functioning mainly as a law court; therefore it need not concern us. The boule, also known as the council of the 500, consisted of members selected by lot evenly from the 10 “tribes” or phulai. It was used mainly to lay down the agenda for the discussion in the ekklesia and to see to it that the decrees were carried out. Membership being determined by lot was useful way of making sure that the boule did not gain too much power and did not govern the ekklesia. The ekklesia was where the main discussion took place. It met four times in each of the ten months (so on every ninth day), and the matters suggested by the boule, such as military operations or the grain supply were then first discussed and voted upon. Any citizen was permitted to stand up and address the whole assembly, but usually only several “regular” speakers would make speeches.

The Pnyx, where the ekklesia met, in the foreground, with the Acropolis in the background.

However when examining the ekklesia one thing is painfully eye-catching: While the voting citizen body consisted of 50 000 males, the ekklesia could only hold 6 000, and 5 000 were usually present. Why then is this number so low? Before proceeding further, it must be fundamental to our understanding of Athenian democracy that the polis of Athens did not merely include the city itself, but the whole of Attica, which except for Athens itself was fairly rural and agricultural. Attica covered an area of 2500 sq. km, which can be compared to the size of modern-day Luxembourg. So the Athenian citizens with voting rights were not concentrated in the city of Athens, but were spread about the countryside. It would take many of the farmers a whole day to walk to Athens, attend the ekklesia and walk back. During this day he would be unable to perform any work on his farm, so he would loose a valuable working day. Later on pay was introduced for the attendance of the ekklesia on the democratic principle that nobody should be excluded from the democracy on the basis of poverty and the Pnyx (where the ekklesia met) was enlarged, but the journey to Athens was still long and arduous and prevented many from attending. Furthermore we must consider that especially during wartime citizens would be away from Athens. During the 5th and most of the 4th century Athens was at war on average for three years out of every four. This meant the citizens would be away serving in the army or in the navy and unable to attend the ekklesia. So for various reasons the ekklesia was always far from full and on average was only visited by every tenth person who was eligible. A potential problem which could arise from this is that mainly the upper classes were represented in the assembly, for it was the poorer population that lived on country farms or served in the navy as rowers (a job as a rower was a secure and well-paid job for the lower social classes).

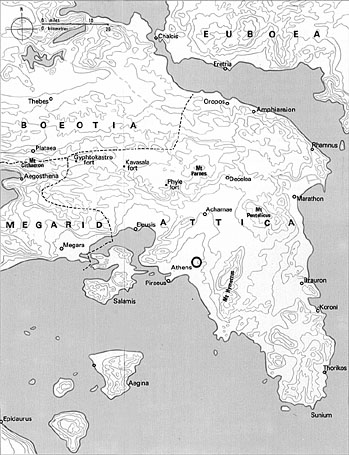

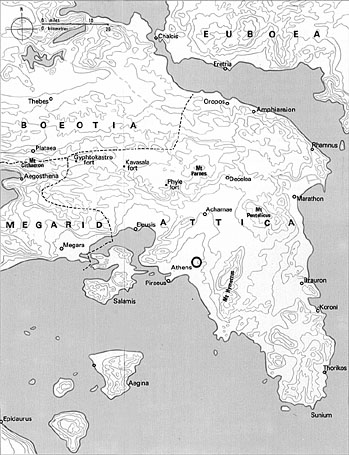

A map of ancient Attica with its borders represented.

The problem outlined above that involvement in the democracy would hinder one’s own work has other implications. Many modern historians argue that one of the foundations of Athenian democracy was the ready availability of slaves. With slaves to perform the work when was not at home but debating in the ekklesia political involvement became affordable for many. In the city, almost all Athenian citizens did not work in factories themselves but instead owned them and supplied them with slaves. This left them with enough time to attend the political meetings. In the country, farm hands were available, but the distance was still a deterrence. In fact, of the 300 000 people living in Athens at least one third must have been slaves. However some modern historians, like Cornelius Castoriadis, do not share the view that democracy resulted directly from the availability of slave labour. He argues that many other societies had a large proportion of slaves but did not become democracies. In fact, slavery only resulted from the 6th century democratically-styled reforms of Solon who eliminated debt-slavery as a source of slaves.

Let us examine more closely what took place before decrees were passed and decisions taken in the ekklesia. Before a vote was taken a herald would announce “Who wishes to speak?” and any citizen could step forward. However ordinary citizens rarely stepped forward as they lacked the skill to speak persuasively. Therefore there was a group of speakers or rhetores (c.f. Latin orator) who would step forward to outline their views or particular loose political groups which they may have been members of. There were no political parties as such but groups of people who shared common ideologies. These speakers were members of the intellectual elite of Athens, and hence also of the financial elite. For an education in the art of persuasive talking required enough time and money to pursue, which were only available to the wealthier citizens. Thus the speakers in the assembly were not part of “the people” as such but rather members of an exclusive elite. This does not mean, however, that they put forward proposals in their own favour, far from it – often the aristocrats tried to outdo each other in the amount of favour they gained from the masses, which they hoped to attain through proposing “democratic” measures, i.e. those which gave more power to the people. So eventually Athens became more democratic through this process of attempting to please the people.

There were also other restraints on the amount of upper class control of politics. It was a risky business, since proposals that were illegal faced prosecution. A speaker could easily find himself entwined in a case at court for what he had said in the assembly, so he would think twice about saying certain things or getting involved at all. Another check on potentially powerful individuals was a process called ostracism. Each year it was decided whether an ostracism should be held or not. If one took place, every citizen could scratch onto a potsherd the name of a man whom he wanted to see expelled from the city, for whatever reason. The one with the most votes was the ostracised, i.e. exiled from the city for ten years. This was often counterproductive, as the exiled person would defect to the enemy (Persia or Sparta) and divulge information to them. It was nevertheless a convenient way for the people to prevent individuals from gaining too much power or removing those who threatened the democracy and the established order.

Many of the regular speakers in the assemblies were of the ten generals or strategoi. This was the only post assigned by a vote so a certain popularity was required to exercise it. The prime example for such a personality is Pericles (495 – 429), who was both skilled military commander and gifted rhetorician. He held the office of strategos for fourteen consecutive years, which shows how popular he was. Thucydides wrote of him as “the first of the Athenians, the most powerful in speech and in action”[1]. He was to be the last man who combined the office of strategos with that of the speaker in the assemblies. Later on, these roles were separated and there were generals who specialised in campaigning and were distinct from the orators and speechmakers.

A bust of Pericles, the famous statesman, orator and general.

An important question we must ask is how the ancient sources treat democracy, as we know most about it from them. The first evidence of democracy stems from Herodotus, from what is known as “the Persian debate”. In this probably fictitious debate, which was essentially Athenian but placed into Persian mouths, three speakers in turn argue for monarchy, oligarchy and democracy (though here the word isonomia, “rule by all” is used). However most of the other ancient sources we have are opposed to the radical democracy. Plato also favoured the principles of freedom (eleutheria) and equality (compounds of iso-) which were key aspects of the democracy, and goes even further to suggest the voting and tenure of offices by women. However he was opposed to the rule of the people, which he argued was unfit for ruling because government required skill which the people did not have. He saw democracy as little more than a mob-rule (or ochlocracy) and instead proposed a ruling elite of philosophers or “guardians”. He argued that the people did not know enough about public affairs to decide for themselves, and could hold no more than opinions at best.

Most anti-democrats however opposed democracy not for philosophical reasons, but because they saw the people as the mass who was having more of a say than them, the elite. A prime example of such a critic is a pamphleteer known to us only as the “Old Oligarch”, who was most certainly a member of the upper class. He basically claims that democracy is appalling, since it represents the rule of the poor, ignorant and fickle majority over the socially and intellectually superior minority, which is the opposite of the way it ought to be. Xenophon in his Memoirs of Socrates gives a fictitious account of the youthful Alcibiades conversing with the older Pericles and places the following words into the mouth of Alcibiades: “So democracy is really just another form of tyranny?”[2] This sums up the opinion of a large proportion of the upper class very well. One of the most disastrous events for Athenian democracy occurred after the naval victory at Arginusai in 406, where the Athenians won a victory but suffered large losses. They placed the blame on the generals, whom they accused of not having saved enough men from drowning. They demanded their execution, but even if they were to blame, that would have been completely unconstitutional. When the people’s request was refused, they pressed the officials until they could have their way and vote on the executions. The executions were carried out and remained a prime example of the fickleness and rashness of the “mob”, and were an event quickly cited by anti-democrats.

Comic playwrights also used their works to express their political views, albeit more subtly than anonymous pamphleteers. Aristophanes’ Knights includes a character called Demos who is portrayed in a ridiculous fashion. A lawsuit was promptly filed by an individual who believed that the democratic institutions were being attacked; however Aristophanes was acquitted in the end. It is significant though that it was permissible to attack individuals or politicians, but not the people or democracy as a whole. Here we may return to the “Old Oligarch” who complains that “they do not permit the people to be ill spoken of in comedy, so that they may not have a bad reputation; but if anyone wants to attack private persons, they bid him do so, knowing perfectly well that the person so treated in comedy does not, for the most part, come from the populace and mass of people but is a person of either wealth, high birth, or influence.”[3]

Bust of the comic playwright Aristophanes.

In the end, opponents and proponents of Athenian democracy have valid points which they fling at each other, even still today. However those modern democrats who are opposed to the radical democracy on the grounds of infeasibility in large modern nations can no longer argue convincingly, since the advent of the internet and interactive television has opened the possibility of a teledemocracy or e-democracy. It would be easy enough to create a system where voters must only hit buttons on their remote control to vote on issues presented on the television. When confronted with this, the modern democrats will contrive a new argument, that it is best to let representatives rule for you instead of ruling yourself. Especially the elite classes will return to the objection of old, calling a democracy a mob-rule. But why then was Athens the Aegean superpower during the democracy, why were freedom and equality guaranteed every citizen? Surely this would not have been the case if it would have merely been a tyranny controlled and condoned by all. Athenian democracy was radical, but it was radically innovative and remarkably near to 20th century democratic ideals. Especially the principle that nobody should be excluded from the democracy on the basis of poverty, which meant that pay was introduced for attending assemblies and for jurorship. This astoundingly modern sounding principle was something completely unique in history, and even today becoming involved in local government is voluntary and entails no pay. So we must recognise the Athenian democracy as a groundbreaking innovation, which despite some negative connotations of mob-rule and ochlocracy was essentially a government by the people, for the people, and guaranteed for the security and liberty of its citizens to an extent which was unique in pre-modern times.

Bibliography

A bibliography for anyone interested in my sources or willing to do further reading:

[1.] Thucydides quoted in J. Ober, Mass and elite in democratic Athens (1989)

[2.] P. Cartledge, Critics and Critiques of Ancient and Athenian Democracy

[3.] Pseudo-Xenophon or “Old Oligarch”, Constitution of Athens in Loeb Edition Xenophon Volume VII

Other sources:

Joint Association of Classical Teachers, The World of Athens (1984)

Hansen, Was Athens a Democracy?

P. Cartledge, Aristophanes and his Theatre of the Absurd

After the positive feedback for the article I posted here earlier on the outbreak of the Second Punic War, I've decided to post another one of my essays. As some of you may know, I'm now studying Classics at Cambridge, which involves writing an essay a week and lots of language work. Anyway, I just finished an essay on Athenian Democracy which got positive feedback from my prof and from Rambuchan, who got to proofread it before anyone else. So the essay is here, read it if you want to, because I must warn you it is twice as long as the previous essay, counting about 2500 words. So I've added a few pictures to spice it up a bit. All dates in BC unless otherwise stated.

Classical Athenian Democracy - A critical Discussion

The modern term democracy derives from the Ancient Greek word demokratia, which is an amalgamation of the words demos, the people, and kratos, power or sovereignty. For it were the ancient Athenians who pioneered this form of government on a larger scale and gave it its name. However it is important to recognize the differences between our modern concept of democracy and what it meant to the Athenians, and that the two are similar in some aspects but radically different in others.

First of all, the term demos is much more narrow than what we understand by “the people”. In classical Athens the demos excluded women, children under the age of eighteen, slaves and resident foreigners (metics or metoikoi), who had no voting or participation rights. This limited the voting citizen body to a much larger extent than in our modern democracies. In the late 5th century there were around 300 000 people living in Athens, but only 50 000 were allowed to cast votes. We must not forget however, that the exclusion of women and slaves from public matters was commonplace in this time and also long after. Slaves were only freed and given the right to vote in today’s “model” democracy, the United States, in 1865 AD, and women had to wait until 1920 AD to be able to vote. Moreover, the age of eighteen as a boundary for participation is still in use in modern times.

Secondly, Athenian democracy was direct in nature rather than representative as today’s democracies. We elect politicians every few years and let them run the country for us and represent us, rather than getting involved in the process of decision making ourselves. The Athenian democracy, on the other hand, was what we might call a radical democracy, since it interpreted the word democracy very literally or radically to mean the rule of the people in the proper sense, rather than the rule of those few elected by the people. The people would gather in assemblies and vote on matters of importance. These two differences make the Athenian democracy substantially dissimilar to our modern democracy. The first difference limits the participation of the people by opening it only to relatively few; the second increases it through the high level of individual participation and involvement.

To further deepen our understanding of Attic democracy the various different councils should be outlined. The three most important councils were the Areopagus, the boule and the ekklesia. The Areopagus lost importance with the advent of democracy around 500, and continued functioning mainly as a law court; therefore it need not concern us. The boule, also known as the council of the 500, consisted of members selected by lot evenly from the 10 “tribes” or phulai. It was used mainly to lay down the agenda for the discussion in the ekklesia and to see to it that the decrees were carried out. Membership being determined by lot was useful way of making sure that the boule did not gain too much power and did not govern the ekklesia. The ekklesia was where the main discussion took place. It met four times in each of the ten months (so on every ninth day), and the matters suggested by the boule, such as military operations or the grain supply were then first discussed and voted upon. Any citizen was permitted to stand up and address the whole assembly, but usually only several “regular” speakers would make speeches.

The Pnyx, where the ekklesia met, in the foreground, with the Acropolis in the background.

However when examining the ekklesia one thing is painfully eye-catching: While the voting citizen body consisted of 50 000 males, the ekklesia could only hold 6 000, and 5 000 were usually present. Why then is this number so low? Before proceeding further, it must be fundamental to our understanding of Athenian democracy that the polis of Athens did not merely include the city itself, but the whole of Attica, which except for Athens itself was fairly rural and agricultural. Attica covered an area of 2500 sq. km, which can be compared to the size of modern-day Luxembourg. So the Athenian citizens with voting rights were not concentrated in the city of Athens, but were spread about the countryside. It would take many of the farmers a whole day to walk to Athens, attend the ekklesia and walk back. During this day he would be unable to perform any work on his farm, so he would loose a valuable working day. Later on pay was introduced for the attendance of the ekklesia on the democratic principle that nobody should be excluded from the democracy on the basis of poverty and the Pnyx (where the ekklesia met) was enlarged, but the journey to Athens was still long and arduous and prevented many from attending. Furthermore we must consider that especially during wartime citizens would be away from Athens. During the 5th and most of the 4th century Athens was at war on average for three years out of every four. This meant the citizens would be away serving in the army or in the navy and unable to attend the ekklesia. So for various reasons the ekklesia was always far from full and on average was only visited by every tenth person who was eligible. A potential problem which could arise from this is that mainly the upper classes were represented in the assembly, for it was the poorer population that lived on country farms or served in the navy as rowers (a job as a rower was a secure and well-paid job for the lower social classes).

A map of ancient Attica with its borders represented.

The problem outlined above that involvement in the democracy would hinder one’s own work has other implications. Many modern historians argue that one of the foundations of Athenian democracy was the ready availability of slaves. With slaves to perform the work when was not at home but debating in the ekklesia political involvement became affordable for many. In the city, almost all Athenian citizens did not work in factories themselves but instead owned them and supplied them with slaves. This left them with enough time to attend the political meetings. In the country, farm hands were available, but the distance was still a deterrence. In fact, of the 300 000 people living in Athens at least one third must have been slaves. However some modern historians, like Cornelius Castoriadis, do not share the view that democracy resulted directly from the availability of slave labour. He argues that many other societies had a large proportion of slaves but did not become democracies. In fact, slavery only resulted from the 6th century democratically-styled reforms of Solon who eliminated debt-slavery as a source of slaves.

Let us examine more closely what took place before decrees were passed and decisions taken in the ekklesia. Before a vote was taken a herald would announce “Who wishes to speak?” and any citizen could step forward. However ordinary citizens rarely stepped forward as they lacked the skill to speak persuasively. Therefore there was a group of speakers or rhetores (c.f. Latin orator) who would step forward to outline their views or particular loose political groups which they may have been members of. There were no political parties as such but groups of people who shared common ideologies. These speakers were members of the intellectual elite of Athens, and hence also of the financial elite. For an education in the art of persuasive talking required enough time and money to pursue, which were only available to the wealthier citizens. Thus the speakers in the assembly were not part of “the people” as such but rather members of an exclusive elite. This does not mean, however, that they put forward proposals in their own favour, far from it – often the aristocrats tried to outdo each other in the amount of favour they gained from the masses, which they hoped to attain through proposing “democratic” measures, i.e. those which gave more power to the people. So eventually Athens became more democratic through this process of attempting to please the people.

There were also other restraints on the amount of upper class control of politics. It was a risky business, since proposals that were illegal faced prosecution. A speaker could easily find himself entwined in a case at court for what he had said in the assembly, so he would think twice about saying certain things or getting involved at all. Another check on potentially powerful individuals was a process called ostracism. Each year it was decided whether an ostracism should be held or not. If one took place, every citizen could scratch onto a potsherd the name of a man whom he wanted to see expelled from the city, for whatever reason. The one with the most votes was the ostracised, i.e. exiled from the city for ten years. This was often counterproductive, as the exiled person would defect to the enemy (Persia or Sparta) and divulge information to them. It was nevertheless a convenient way for the people to prevent individuals from gaining too much power or removing those who threatened the democracy and the established order.

Many of the regular speakers in the assemblies were of the ten generals or strategoi. This was the only post assigned by a vote so a certain popularity was required to exercise it. The prime example for such a personality is Pericles (495 – 429), who was both skilled military commander and gifted rhetorician. He held the office of strategos for fourteen consecutive years, which shows how popular he was. Thucydides wrote of him as “the first of the Athenians, the most powerful in speech and in action”[1]. He was to be the last man who combined the office of strategos with that of the speaker in the assemblies. Later on, these roles were separated and there were generals who specialised in campaigning and were distinct from the orators and speechmakers.

A bust of Pericles, the famous statesman, orator and general.

An important question we must ask is how the ancient sources treat democracy, as we know most about it from them. The first evidence of democracy stems from Herodotus, from what is known as “the Persian debate”. In this probably fictitious debate, which was essentially Athenian but placed into Persian mouths, three speakers in turn argue for monarchy, oligarchy and democracy (though here the word isonomia, “rule by all” is used). However most of the other ancient sources we have are opposed to the radical democracy. Plato also favoured the principles of freedom (eleutheria) and equality (compounds of iso-) which were key aspects of the democracy, and goes even further to suggest the voting and tenure of offices by women. However he was opposed to the rule of the people, which he argued was unfit for ruling because government required skill which the people did not have. He saw democracy as little more than a mob-rule (or ochlocracy) and instead proposed a ruling elite of philosophers or “guardians”. He argued that the people did not know enough about public affairs to decide for themselves, and could hold no more than opinions at best.

Most anti-democrats however opposed democracy not for philosophical reasons, but because they saw the people as the mass who was having more of a say than them, the elite. A prime example of such a critic is a pamphleteer known to us only as the “Old Oligarch”, who was most certainly a member of the upper class. He basically claims that democracy is appalling, since it represents the rule of the poor, ignorant and fickle majority over the socially and intellectually superior minority, which is the opposite of the way it ought to be. Xenophon in his Memoirs of Socrates gives a fictitious account of the youthful Alcibiades conversing with the older Pericles and places the following words into the mouth of Alcibiades: “So democracy is really just another form of tyranny?”[2] This sums up the opinion of a large proportion of the upper class very well. One of the most disastrous events for Athenian democracy occurred after the naval victory at Arginusai in 406, where the Athenians won a victory but suffered large losses. They placed the blame on the generals, whom they accused of not having saved enough men from drowning. They demanded their execution, but even if they were to blame, that would have been completely unconstitutional. When the people’s request was refused, they pressed the officials until they could have their way and vote on the executions. The executions were carried out and remained a prime example of the fickleness and rashness of the “mob”, and were an event quickly cited by anti-democrats.

Comic playwrights also used their works to express their political views, albeit more subtly than anonymous pamphleteers. Aristophanes’ Knights includes a character called Demos who is portrayed in a ridiculous fashion. A lawsuit was promptly filed by an individual who believed that the democratic institutions were being attacked; however Aristophanes was acquitted in the end. It is significant though that it was permissible to attack individuals or politicians, but not the people or democracy as a whole. Here we may return to the “Old Oligarch” who complains that “they do not permit the people to be ill spoken of in comedy, so that they may not have a bad reputation; but if anyone wants to attack private persons, they bid him do so, knowing perfectly well that the person so treated in comedy does not, for the most part, come from the populace and mass of people but is a person of either wealth, high birth, or influence.”[3]

Bust of the comic playwright Aristophanes.

In the end, opponents and proponents of Athenian democracy have valid points which they fling at each other, even still today. However those modern democrats who are opposed to the radical democracy on the grounds of infeasibility in large modern nations can no longer argue convincingly, since the advent of the internet and interactive television has opened the possibility of a teledemocracy or e-democracy. It would be easy enough to create a system where voters must only hit buttons on their remote control to vote on issues presented on the television. When confronted with this, the modern democrats will contrive a new argument, that it is best to let representatives rule for you instead of ruling yourself. Especially the elite classes will return to the objection of old, calling a democracy a mob-rule. But why then was Athens the Aegean superpower during the democracy, why were freedom and equality guaranteed every citizen? Surely this would not have been the case if it would have merely been a tyranny controlled and condoned by all. Athenian democracy was radical, but it was radically innovative and remarkably near to 20th century democratic ideals. Especially the principle that nobody should be excluded from the democracy on the basis of poverty, which meant that pay was introduced for attending assemblies and for jurorship. This astoundingly modern sounding principle was something completely unique in history, and even today becoming involved in local government is voluntary and entails no pay. So we must recognise the Athenian democracy as a groundbreaking innovation, which despite some negative connotations of mob-rule and ochlocracy was essentially a government by the people, for the people, and guaranteed for the security and liberty of its citizens to an extent which was unique in pre-modern times.

Bibliography

A bibliography for anyone interested in my sources or willing to do further reading:

[1.] Thucydides quoted in J. Ober, Mass and elite in democratic Athens (1989)

[2.] P. Cartledge, Critics and Critiques of Ancient and Athenian Democracy

[3.] Pseudo-Xenophon or “Old Oligarch”, Constitution of Athens in Loeb Edition Xenophon Volume VII

Other sources:

Joint Association of Classical Teachers, The World of Athens (1984)

Hansen, Was Athens a Democracy?

P. Cartledge, Aristophanes and his Theatre of the Absurd

Perhaps there should also be a poll, about e-democracy

Perhaps there should also be a poll, about e-democracy