Adler17

Prussian Feldmarschall

Battle of Jutland

vs.

vs.

Today 90 years ago the two most mighty fleets of their time clashed in the battle of Jutland or Skagerrak, how it is called in Germany. At the dawn of June 1st 8.647 people were dead and 1.017 wounded. 25 ships were lying on the bottom of the sea. Before continuing we should remember the casualities of both sides and also remember men fought the battle, not just ships.

However here is the article.

Also I have to add that the time given here is CEST. Also SMS is the German equivalent to HMS meaning Seiner Majestäts Schiff.

Prelude

When WW1 broke out, Britain and Germany had built the mightiest fleets ever until then. But as soon as the war broke out, the use of these mighty fleets was seen as risky, too risky for some. A lost sea battle would have meant especially for Britain, which had also several problems with some of the Dreadnoughts, the end of the war. But also the Germans, who could still rely on the army, were not willing to risk much.

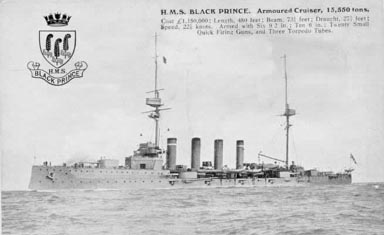

Although both sides fought some engagements with sea battles won and lost, the battleships were not used. So armoured cruiser, light cruiser and destroyer were fighting the war on the seas. Also two weapons relative new came into use: the submarine and the mine. Both were deadly, but especially the mine was seen as too “un- British” in the early days of the war as it was seen as the “weapon of the weak”.

The Germans did not have these doubts and used these weapons with tremendous success during the war. And it is no wonder the British used them, too.

So also the Germans recognized the potential very early. The U-Boats with the success of U 9 against three armoured cruiser 1914, in which HMS Cressy, Hogue, Aboukir were sunk by only one U-Boat within about an hour.

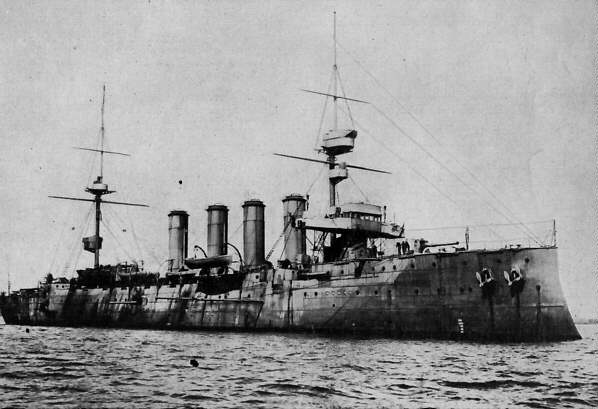

But the fights of the older and smaller ships does not mean the battleships had no losses. In October 1914 the newly rebuilt auxiliary minelayerBerlin was sent to the Irish sea with a deadly freight on her second mission under the command of Captain Pfundheller. The mines should be laid near the Firth of Clyde, but due to the lack of navigation lights and the presence of British warship broadcasts Pfundheller decided to throw the mines near Loch Swilly as the nearest shipping lane. Unknown to him and the German command, Loch Swilly was used as base of the British 2nd battle squadron, a measure made to save the ships from submarine attacks in Scapa Flow until the anti submarine defence was built up. So indeed 200 mines were lying in range of a British squadron equipped with new super dreadnoughts! And these weapons can wait. Berlin was going to Norway via Iceland and was interned at Trondheim at October 26th due to engine problems.

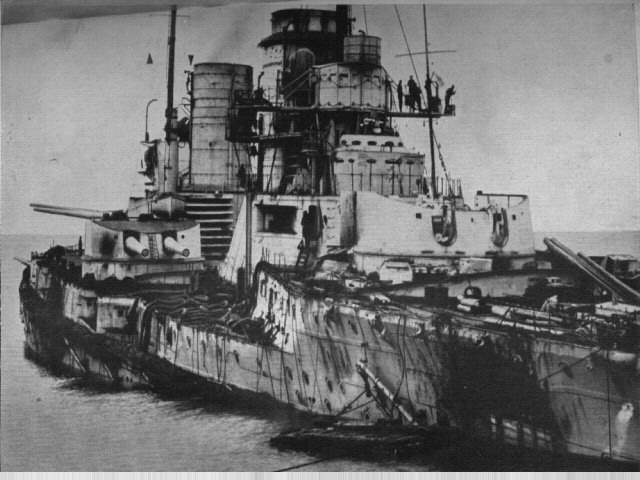

The very next day HMS Audacious in company with HMS Centurion (flagship), Ajax, King George V, Orion, Monarch, Thunderer left the base to conduct a gunnery exercise. HMS Audacious struck a single mine. She sank after she capsized and exploded 12 hours after the hit. It appeared the protection of the battleship against submarine attacks by torpedoes and mines were insufficient by the British ships. Although some problems could be solved, throughout the war the German ships were able to sustain much more damage than their British counter part, but there is much to say later.

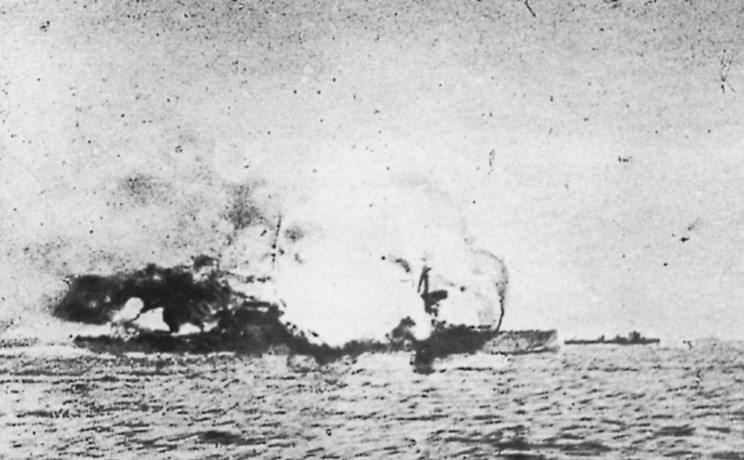

The sinking British battleship HMS Audacious

Although the British Grand Fleet CiC, Admiral Jellicoe, proposed to make that disaster a national secret, all measures to do so were invain as US citizens were witnesses of the loss of the ship. Soon everyone except the British knew it. Despite that the Royal Navy did not admit the loss until after the war!

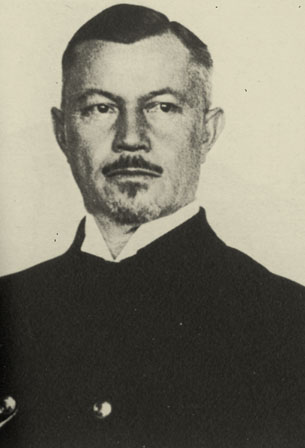

But back to the topic: Indeed both sides were evading a clash of the battleships. This should change dramatically when the command of the fleets turned to two men, who both were ambitious, had courage and who both relied on the power of the crews and ships of their fleets. And both wanted to be victorious. And both indeed had several plans to destroy parts of the fleet until the main fleet of the enemy arrived. The enemy should then be weakened and so the final fight would follow later.

But Scheer would be the first to act. He relied on the plans of 1914, but this time the battleships should stay: Hipper’s battle cruiser should shell British coastal cities. If Beatty tried to save the coast, Scheer, who was with the Hochseeflotte 60 sm away, would then enter the battle and destroy Beatty before Jellicoe would come. Also U-Boats should attack the enemy battle squadrons on their way to the battle so that it was sure, Jellicoe would not appear. To enrage the British twice British town were shelled but on the 24th of April SMS Seydlitz was mined and had to be repaired. Since Scheer needed all of his five battle cruiser he had to delay the whole operation from the 17th to the 30th of May 1916. This also meant the U-Boats mostly had to go home as they did not had enough fuel. And there was another setback: the weather. Scheer originally wanted to use Zeppelins as aerial scouts but due to bad weather (for Zeppelins) they were also useless. In the end Scheer wanted to follow an alternative plan: He wanted to sail to Norway, where Hipper should attack British shipping and so provoke the enemy to come. Also he stayed only 25 miles to be in range if something went wrong. And he had not the heart to deny the pleads of the IInd German Schlachtgeschwader, equipped with Deutschland class predreadnoughts. Although called 5 minutes ships, as this was the time expected to survive a real combat with enemy battleships, Scheer as the former commander of these ships let them drive with the fleet. But the few more guns meant also a reduction of speed of about at least three knots.

At 9.48 AM the SMS Friedrich der Große, flagship of the Hochseeflotte, sent a wireless broadcast to all ships to prepare for an operation beginning at 7.00 PM: 31 Gg 2490. That meant the secret order 2490 had to be executed on May 31st. And he sent, before making the sortie, his sign DK still in harbour to fool the British intelligence.

Of course the British heard that in Room 40, the British intelligence bureau, which heard all the broadcasts of the German ships. The codes were known because after the loss of the light cruiser SMS Magdeburg in the Baltic the Russians got them. But because of quarrels between the Navy command and Room 40 the latter gave only the news to Jellicoe, that Hipper with his battle cruiser were in sea and that Scheer’s sign was still in the Jade Bay at Wilhelmshaven, when they were asked by Rear Admiral Thomas Jackson. They did not say they knew, the sent broadcast was a trap as well as they could hear the entire German fleet. Too often they were not heard to end as the commanding naval officers thought they were good to get the news but not to make conclusions. So also Jellicoe believed to have only some battle cruisers as easy prey. None of the commanders expected nor looked for a clash of the titans.

vs.

vs.

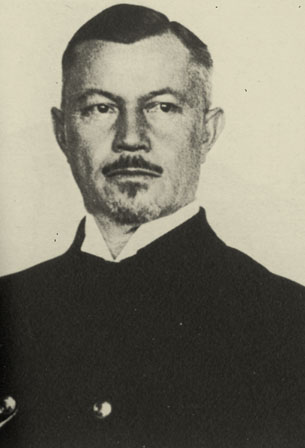

Admiral John Jellicoe vs. Admiral Reinhard Scheer

vs.

vs.

Admiral David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty vs. Admiral Franz Ritter von Hipper

Ordre de Battaille:

As I have here not so much room to show and it could be too much I can only give you a link here:

http://www.navweaps.com/index_oob/OOB_WWI/OOB_WWI_Jutland.htm

All in all left following forces their harbours:

Britain:

28 Battleships, 9 Battle cruiser, 8 armoured cruiser, 26 light cruiser, 77 destroyer, 1 sea plane carrier, 1 minelayer. 149 ships with about 1.250.000 tons and 60.000 men.

Germany:

16 Battleships, 5 Battle cruiser, 6 predreadnoughts, 11 light cruiser, 62 destroyer. 99 ships with 660.000 ts and 45.000 men.

Main guns:

Britain:

48 38.1, 10 35.6, 142 34.3, 144 30.5 cm guns

Germany:

100 28.3, 144 30.5 cm guns

Ship datas of some chosen ships:

HMS Lydiard, destroyer

807 ts

35 kn

3 4” guns and 4 torpedo tubes

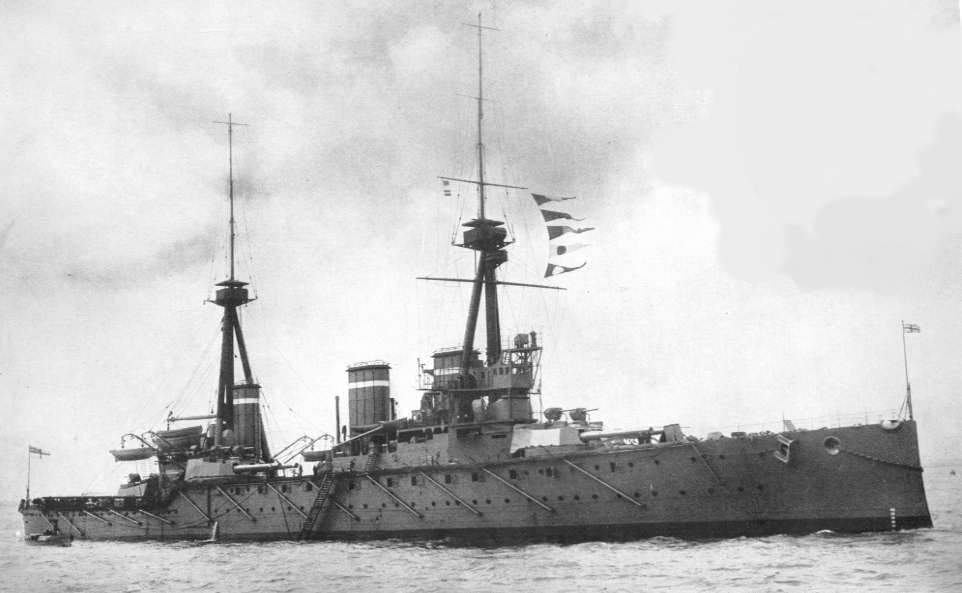

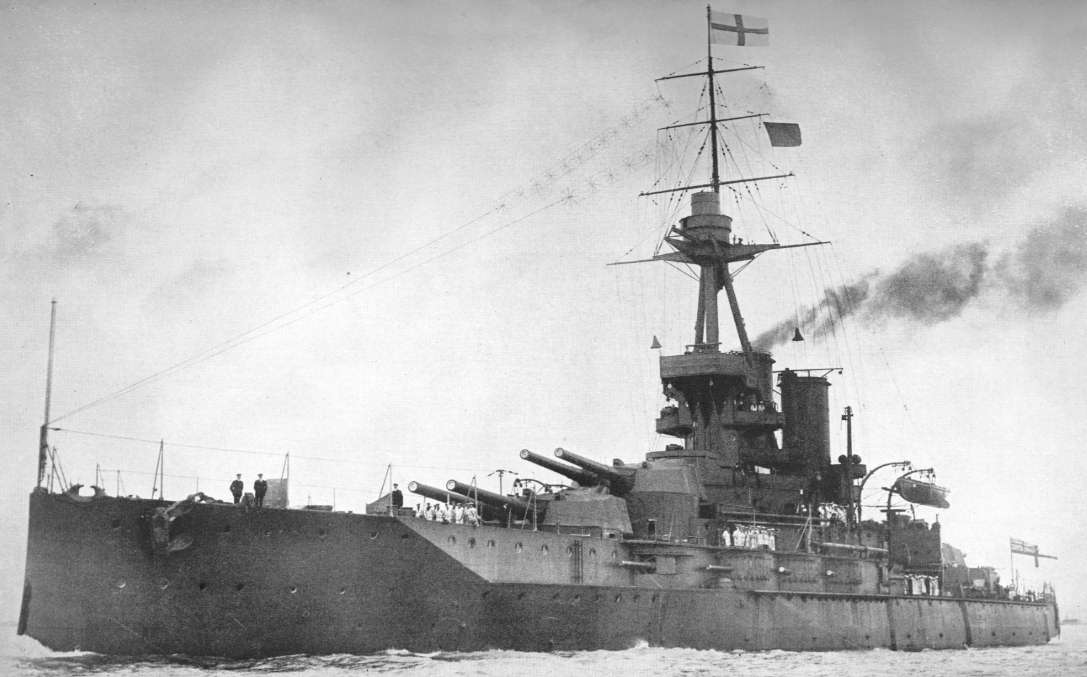

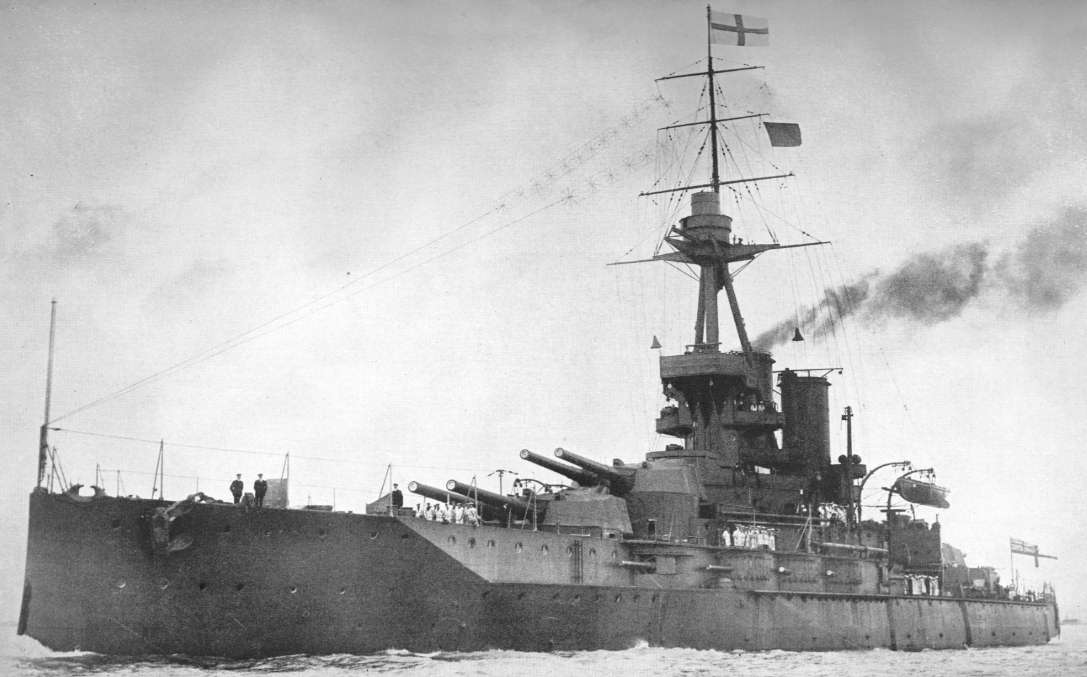

HMS Iron Duke

25.000 ts

21 kn

10 34.3 cm guns (broadside weight of shells: 6.350 kg)

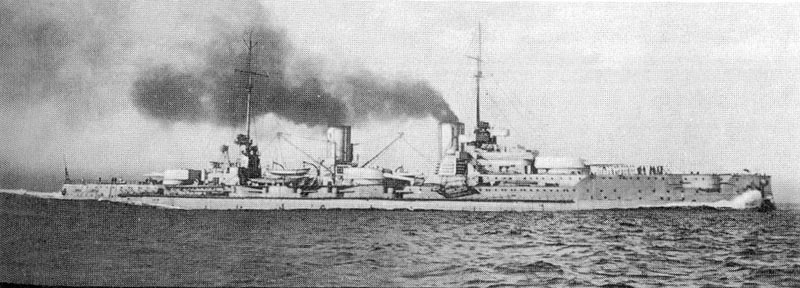

HMS Lion

26.850 ts

29 kn

8 34.3 cm guns

strongest armour: 23 cm

SM V 29

36 kn

3 8.8 cm or (some vessels) 10.5 cm guns

6 torpedo tubes

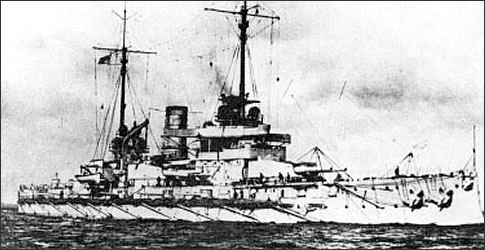

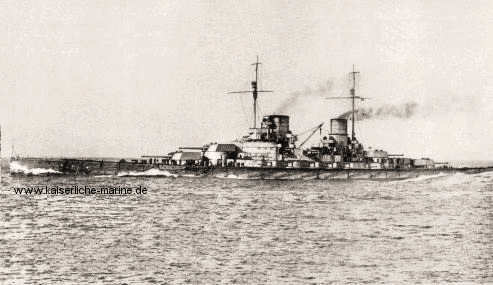

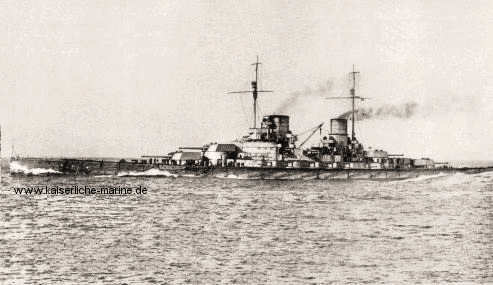

SMS Friedrich der Große

27.000 ts

22.4 kn

10 30.5 cm guns (3856 kg)

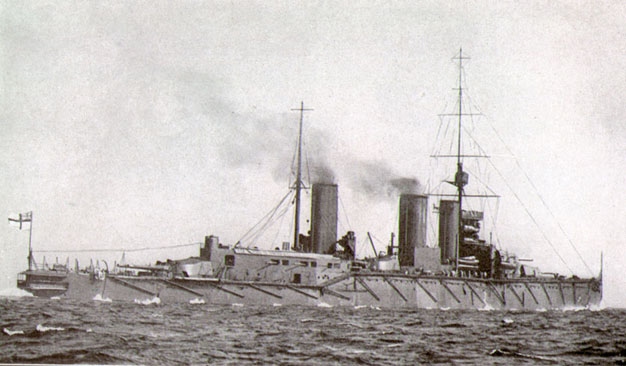

SMS Lützow

26.700 ts

27 kn

8 30.5 cm guns

strongest armour: 33 cm

These datas show different philosophies in ship constructing. While the Germans relied more on armour than on guns, they also relied more having offensive small vessels carrying more torpedoes. So one side had bigger guns, the other better armour, one side did want to stop attacks from small vessels the other conduct them.

The way to battle

Jellicoe and Beatty left their harbours at about 21.30. Jellicoe’s force had to unite as parts of the fleet were based in Cromarty and not Scapa Flow. Also the third battlecuiser squadron of Admiral Sir Horace Hood was with the fleet and not with Beatty as there were no sufficient shooting exercise area in Rosyth, where Beatty came from. Therefore he had in his 52 ships 4 brand new Queen Elizabeth class battleships, Evan Thomas 5th Battle squadron. With their armament of 15” guns they should destroy any enemy in sight. In theory. Indeed Evan Thomas was a pedantic man, who did everything strictly after the rules and orders. And who did not use his brain to take the initiative if needed. That should have later consequences.

At dawn of the new day, May 31st 1916, a warm sun, despite the bad forecasts, sent her first lights to Earth and lighted up the German Hochseeflotte on her way to battle. The forces left the Jade at 2.00 resp. 3.00 o’clock. A battle, which was not planned in the extent by the commanding admirals and the only battle of Dreadnought type warships fighting each other in WW1. But also a battle of complex and bizarre circumstances. Of errors made and heroism- and death. Of mighty ships sunk and famous and unknown man dying.

However before I will continue, as armchair strategist, I will give the word to the only admiral, who made no real mistake: Admiral von Hipper, commander of the German Scout Forces, who said this in a silent phase of the battle: “I bet the armchair strategists at the Naval Academy will one day break their heads on getting to know, what we thought. I mean, we haven’t thought. We were full in action to try to use solid tactical principles.”

He couldn’t be nearer.

Today 90 years ago the two most mighty fleets of their time clashed in the battle of Jutland or Skagerrak, how it is called in Germany. At the dawn of June 1st 8.647 people were dead and 1.017 wounded. 25 ships were lying on the bottom of the sea. Before continuing we should remember the casualities of both sides and also remember men fought the battle, not just ships.

However here is the article.

Also I have to add that the time given here is CEST. Also SMS is the German equivalent to HMS meaning Seiner Majestäts Schiff.

Prelude

When WW1 broke out, Britain and Germany had built the mightiest fleets ever until then. But as soon as the war broke out, the use of these mighty fleets was seen as risky, too risky for some. A lost sea battle would have meant especially for Britain, which had also several problems with some of the Dreadnoughts, the end of the war. But also the Germans, who could still rely on the army, were not willing to risk much.

Although both sides fought some engagements with sea battles won and lost, the battleships were not used. So armoured cruiser, light cruiser and destroyer were fighting the war on the seas. Also two weapons relative new came into use: the submarine and the mine. Both were deadly, but especially the mine was seen as too “un- British” in the early days of the war as it was seen as the “weapon of the weak”.

The Germans did not have these doubts and used these weapons with tremendous success during the war. And it is no wonder the British used them, too.

So also the Germans recognized the potential very early. The U-Boats with the success of U 9 against three armoured cruiser 1914, in which HMS Cressy, Hogue, Aboukir were sunk by only one U-Boat within about an hour.

But the fights of the older and smaller ships does not mean the battleships had no losses. In October 1914 the newly rebuilt auxiliary minelayerBerlin was sent to the Irish sea with a deadly freight on her second mission under the command of Captain Pfundheller. The mines should be laid near the Firth of Clyde, but due to the lack of navigation lights and the presence of British warship broadcasts Pfundheller decided to throw the mines near Loch Swilly as the nearest shipping lane. Unknown to him and the German command, Loch Swilly was used as base of the British 2nd battle squadron, a measure made to save the ships from submarine attacks in Scapa Flow until the anti submarine defence was built up. So indeed 200 mines were lying in range of a British squadron equipped with new super dreadnoughts! And these weapons can wait. Berlin was going to Norway via Iceland and was interned at Trondheim at October 26th due to engine problems.

The very next day HMS Audacious in company with HMS Centurion (flagship), Ajax, King George V, Orion, Monarch, Thunderer left the base to conduct a gunnery exercise. HMS Audacious struck a single mine. She sank after she capsized and exploded 12 hours after the hit. It appeared the protection of the battleship against submarine attacks by torpedoes and mines were insufficient by the British ships. Although some problems could be solved, throughout the war the German ships were able to sustain much more damage than their British counter part, but there is much to say later.

The sinking British battleship HMS Audacious

Although the British Grand Fleet CiC, Admiral Jellicoe, proposed to make that disaster a national secret, all measures to do so were invain as US citizens were witnesses of the loss of the ship. Soon everyone except the British knew it. Despite that the Royal Navy did not admit the loss until after the war!

But back to the topic: Indeed both sides were evading a clash of the battleships. This should change dramatically when the command of the fleets turned to two men, who both were ambitious, had courage and who both relied on the power of the crews and ships of their fleets. And both wanted to be victorious. And both indeed had several plans to destroy parts of the fleet until the main fleet of the enemy arrived. The enemy should then be weakened and so the final fight would follow later.

But Scheer would be the first to act. He relied on the plans of 1914, but this time the battleships should stay: Hipper’s battle cruiser should shell British coastal cities. If Beatty tried to save the coast, Scheer, who was with the Hochseeflotte 60 sm away, would then enter the battle and destroy Beatty before Jellicoe would come. Also U-Boats should attack the enemy battle squadrons on their way to the battle so that it was sure, Jellicoe would not appear. To enrage the British twice British town were shelled but on the 24th of April SMS Seydlitz was mined and had to be repaired. Since Scheer needed all of his five battle cruiser he had to delay the whole operation from the 17th to the 30th of May 1916. This also meant the U-Boats mostly had to go home as they did not had enough fuel. And there was another setback: the weather. Scheer originally wanted to use Zeppelins as aerial scouts but due to bad weather (for Zeppelins) they were also useless. In the end Scheer wanted to follow an alternative plan: He wanted to sail to Norway, where Hipper should attack British shipping and so provoke the enemy to come. Also he stayed only 25 miles to be in range if something went wrong. And he had not the heart to deny the pleads of the IInd German Schlachtgeschwader, equipped with Deutschland class predreadnoughts. Although called 5 minutes ships, as this was the time expected to survive a real combat with enemy battleships, Scheer as the former commander of these ships let them drive with the fleet. But the few more guns meant also a reduction of speed of about at least three knots.

At 9.48 AM the SMS Friedrich der Große, flagship of the Hochseeflotte, sent a wireless broadcast to all ships to prepare for an operation beginning at 7.00 PM: 31 Gg 2490. That meant the secret order 2490 had to be executed on May 31st. And he sent, before making the sortie, his sign DK still in harbour to fool the British intelligence.

Of course the British heard that in Room 40, the British intelligence bureau, which heard all the broadcasts of the German ships. The codes were known because after the loss of the light cruiser SMS Magdeburg in the Baltic the Russians got them. But because of quarrels between the Navy command and Room 40 the latter gave only the news to Jellicoe, that Hipper with his battle cruiser were in sea and that Scheer’s sign was still in the Jade Bay at Wilhelmshaven, when they were asked by Rear Admiral Thomas Jackson. They did not say they knew, the sent broadcast was a trap as well as they could hear the entire German fleet. Too often they were not heard to end as the commanding naval officers thought they were good to get the news but not to make conclusions. So also Jellicoe believed to have only some battle cruisers as easy prey. None of the commanders expected nor looked for a clash of the titans.

Admiral John Jellicoe vs. Admiral Reinhard Scheer

Admiral David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty vs. Admiral Franz Ritter von Hipper

Ordre de Battaille:

As I have here not so much room to show and it could be too much I can only give you a link here:

http://www.navweaps.com/index_oob/OOB_WWI/OOB_WWI_Jutland.htm

All in all left following forces their harbours:

Britain:

28 Battleships, 9 Battle cruiser, 8 armoured cruiser, 26 light cruiser, 77 destroyer, 1 sea plane carrier, 1 minelayer. 149 ships with about 1.250.000 tons and 60.000 men.

Germany:

16 Battleships, 5 Battle cruiser, 6 predreadnoughts, 11 light cruiser, 62 destroyer. 99 ships with 660.000 ts and 45.000 men.

Main guns:

Britain:

48 38.1, 10 35.6, 142 34.3, 144 30.5 cm guns

Germany:

100 28.3, 144 30.5 cm guns

Ship datas of some chosen ships:

HMS Lydiard, destroyer

807 ts

35 kn

3 4” guns and 4 torpedo tubes

HMS Iron Duke

25.000 ts

21 kn

10 34.3 cm guns (broadside weight of shells: 6.350 kg)

HMS Lion

26.850 ts

29 kn

8 34.3 cm guns

strongest armour: 23 cm

SM V 29

36 kn

3 8.8 cm or (some vessels) 10.5 cm guns

6 torpedo tubes

SMS Friedrich der Große

27.000 ts

22.4 kn

10 30.5 cm guns (3856 kg)

SMS Lützow

26.700 ts

27 kn

8 30.5 cm guns

strongest armour: 33 cm

These datas show different philosophies in ship constructing. While the Germans relied more on armour than on guns, they also relied more having offensive small vessels carrying more torpedoes. So one side had bigger guns, the other better armour, one side did want to stop attacks from small vessels the other conduct them.

The way to battle

Jellicoe and Beatty left their harbours at about 21.30. Jellicoe’s force had to unite as parts of the fleet were based in Cromarty and not Scapa Flow. Also the third battlecuiser squadron of Admiral Sir Horace Hood was with the fleet and not with Beatty as there were no sufficient shooting exercise area in Rosyth, where Beatty came from. Therefore he had in his 52 ships 4 brand new Queen Elizabeth class battleships, Evan Thomas 5th Battle squadron. With their armament of 15” guns they should destroy any enemy in sight. In theory. Indeed Evan Thomas was a pedantic man, who did everything strictly after the rules and orders. And who did not use his brain to take the initiative if needed. That should have later consequences.

At dawn of the new day, May 31st 1916, a warm sun, despite the bad forecasts, sent her first lights to Earth and lighted up the German Hochseeflotte on her way to battle. The forces left the Jade at 2.00 resp. 3.00 o’clock. A battle, which was not planned in the extent by the commanding admirals and the only battle of Dreadnought type warships fighting each other in WW1. But also a battle of complex and bizarre circumstances. Of errors made and heroism- and death. Of mighty ships sunk and famous and unknown man dying.

However before I will continue, as armchair strategist, I will give the word to the only admiral, who made no real mistake: Admiral von Hipper, commander of the German Scout Forces, who said this in a silent phase of the battle: “I bet the armchair strategists at the Naval Academy will one day break their heads on getting to know, what we thought. I mean, we haven’t thought. We were full in action to try to use solid tactical principles.”

He couldn’t be nearer.

, when he got the news. Because both ships, HMS Galathea and HMS Lion were out of sight of Jellicoe, HMS Galathea gave a broadcast message to HMS Iron Duke. The broadcast messages were seen as not very reliable especially in battles and so avoided if possible in the Royal Navy. However the flag signs of HMS Lion were infamous for their visibility. Or better non- visibility.

, when he got the news. Because both ships, HMS Galathea and HMS Lion were out of sight of Jellicoe, HMS Galathea gave a broadcast message to HMS Iron Duke. The broadcast messages were seen as not very reliable especially in battles and so avoided if possible in the Royal Navy. However the flag signs of HMS Lion were infamous for their visibility. Or better non- visibility.