privatehudson

The Ultimate Badass

- Joined

- Oct 15, 2003

- Messages

- 4,821

Operation Biting – The Red Devils Win Their Spurs

Why Bruneval?

When I was young my relatives would buy me an annual for Christmas. This usually involved “boy’s own” style comic stories about war, sporting prowess or superheroes. As I grew up I collected other annuals in a similar theme, including many from the years before I was born. A Victor annual from 1969 contained a story about a raid on the radar station at Bruneval (known as Operation Biting) that caught my attention since it described the an early operation carried out by British Paratroopers. I was also interested to notice that the British commander was a man familiar to me from reading about of the Market Garden Campaign, Major John Frost.

Information on the raid was difficult to locate at the time because I didn’t have access to the Internet, so it was many years before I managed to get more information. Within a short space of time I acquired an “after the battle” magazine containing an article on the raid, an article written by Frost many years after the war and a book on British paratroopers which had a brief section on the operation. I found that the real story was every bit as interesting as any comic book tale, and hopefully you will too.

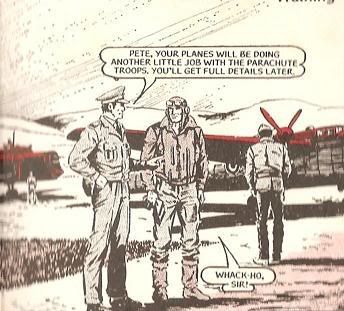

A typical panel of the Victor story complete with an interesting take on how RAF pilots spoke during the war!

Historical Background to the raid

By late 1941 the British had been aware for some time that the Germans had been operating an early warning radar system known as Freya on the coast, which ran at 125 megacycles. A mystery had arisen however because signals had been recently received at 570 megacycles, suggesting a new system was being used. By this time the Directory of Intelligence at the Air Ministry had located a probable 27 sites for Freya from Bodo in Norway to Bordeaux in France. The origin of the 570 megacyle signal could be any one of these sites, and obviously it would be impossible to destroy all of them permanently.

Faced with this thorny problem Dr. Charles Frank a physicist who worked at the Directorate began to study the sites to try to determine any anomalies. When he looked at medium level reconnaissance of the Bruneval Site (located on the North Coast of France near Le Harve) he noticed something very strange. The site was located very close to high cliffs, with the Freya aerials located a short distance from a large building and connected to it by a path. The photos that Frank was studying however showed a large black object located midway between the cliff edge and the house, with a path connecting the two. It could be that the object was merely part of the Freya system, or it could be the elusive origin of the new signals, the Wurzburg system.

A few days after Frank’s discovery Flight Lieutenant Tony Hill paid a visit to the photo interpretation centre in Medmenham. He had been involved in numerous low level photo missions over the 27 radar stations, and the centre’s commander, aware of Frank’s interest mentioned the object to Hill. Not waiting for orders Hill decided to take off the next day and flew in low over the site and managed to get back out again before any of the Germans realised he was there. Upon returning however he discovered that his camera had failed! He was able to confirm however that the object appeared to be like “an electric bowl fire about 10 feet across”. If correct he had almost certainly found the elusive origin of the 570 transmissions.

Victor’s attempt to portray Hill’s flight got the plane wrong, he actually flew a Spitfire photo reconnaissance plane.

Despite the risks Hill repeated the feat the very next day, and this time returned with a photo of the site that confirmed everything he had said. This did not however prove beyond doubt that the radar transmitted on 570 megacycles, and until then nothing could be done to counter it. It was at this point that a raid was considered to snatch the system and as much information on it as possible. Commandos were ruled out almost immediately as the Bruneval site lay at the top of high cliffs, and was heavily defended. At this point it was suggested by Lord Louis Mountbatten that Paratroopers could be used for the raid. It was a bold suggestion since for the British this was a virtually untried form of warfare.

Hill’s famous photograph from his second flight. Its perhaps worth noting that the clarity of the photo worried the paratroopers who felt that Hill must have flown so low that the Germans would guess a raid was imminent.

Origins of Britain’s Paratroopers

Parachute troops were a relatively new development in warfare but as the Germans had so recently demonstrated in Crete, Corinth, the Low Countries and Norway they certainly had their value when employed correctly. The British began to experiment in the field after the fall of France in 1940 with Churchill ordering the formation of a 5,000 strong force with the aim of taking the war back to the continent in small scale raids. Based out of Ringway airbase in Manchester (which later became the city’s international airport) training began as early as the July 1940 using 6 Whitley bombers as transport craft. Real progress was slow however and opposition high, especially in the ranks of the RAF. They felt it was frittering away their precious resources that could be better employed on the defence of the home islands and strategic bombing. These first units still operated under the title of commandos but were soon reformed as wings of the No 11 Special Air Service Battallion. This formation is not to be confused with the more famous SAS regiment founded by David Stirling, as they were separate formations.

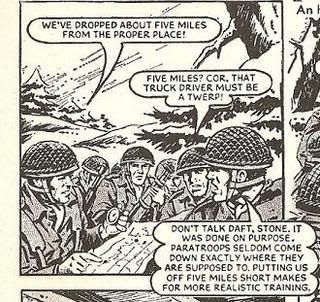

Despite lack of resources training tried to be as accurate as possible and reflect the fortunes of war.

The first test of No 11 SAS was a raid to destroy the Tragino aqueduct in southern Italy. Around two million inhabitants of the surrounding area relied on the aqueduct to provide water, and it was felt that destroying it would create panic and damage the Italian war effort. Forty officers and men took part in the raid, which was launched from Malta, landing the raiders at night within a short distance of the target. The raiders were able to destroy the aqueduct without much trouble, also succeeding in destroying a nearby bridge to hinder the reaction of any local police troops. The raiders then split up in order to make their way to the coast but unknown to them the submarine assigned to pick them up had been ordered not to sail. One of the Whitley’s assigned to provide a diversionary raid suffered engine problems and radioed that it was forced down almost right on top of the pick-up spot, causing fears that the pick-up would be compromised.

Every single one of the raiders were captured over the next few days, and one of the Italian interpreters (who was an anti-fascist) attached to the raid was shot by local militia. Whilst Colossus provided mixed results it did prove that it was practical to drop parachute troops into enemy controlled county at night. Knowing this was crucial to the decision to employ paratroopers for the Bruneval raid as that would require a night assault. By this time the original 11 SAS had been reformed as the 1st Parachute Battalion, part of the newly raised 1st Parachute Brigade which was due to be part of Britain’s first parachute division to be commanded by Major General F.A.M Browning.

Planning for the raid

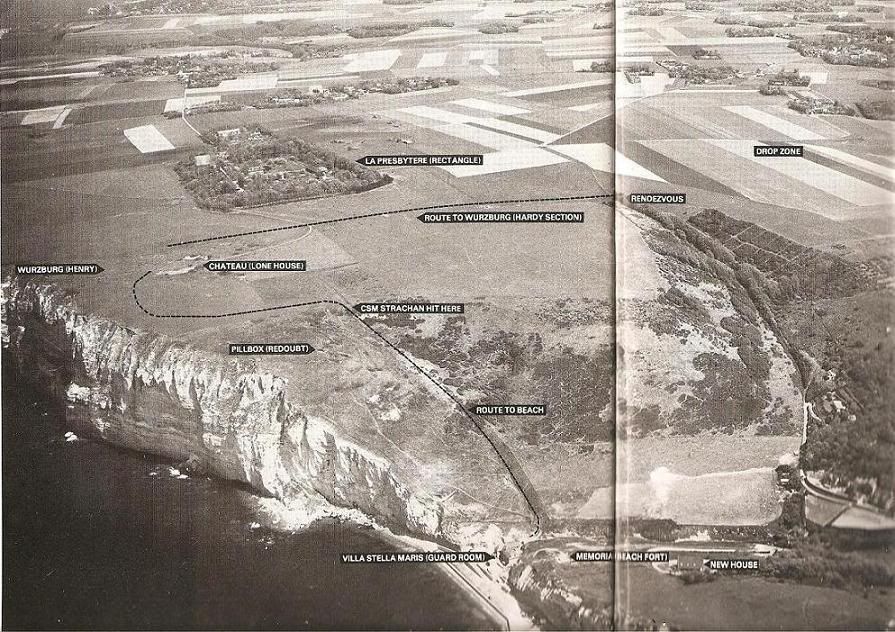

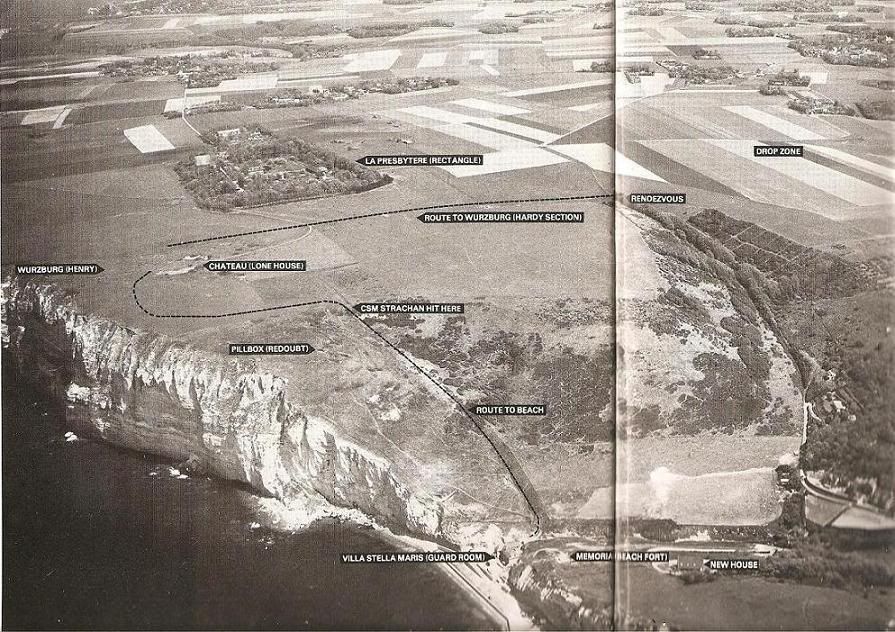

Having established that the raid would be conducted by parachute troops the task was assigned to Major John Frost’s “C” company of the 2nd Parachute Battalion. Also attached would be a team of 7 men from the Royal Engineers and Flight Sergeant Cox, a RAF radar operator. Frost planned to drop a short distance inland from the target and after forming up split into 3 main groups. Some of what I will describe next can be seen on the scanned photo below which I appreciate is not great quality, but hopefully will be sufficient visual aid to the action described.

Nelson, commanded by Lieutenant Charteris would move directly towards the beach and secure it. On the way he would be expected to clear the cliffs near the beach and move into Bruneval Village (the edge of which is barely in photo at the bottom right). Note that the “route to beach” marker on the photo indicates the route Frost and the main force used, and is not an indication of Chatteris’ intended route.

The next force was allocated to making the main attack towards the radar so split further into three groups. Jellicoe under Peter Young was to move straight to the radar installation and secure it for the Royal Engineers to move in and complete their work. Hardy group, which was commanded by Frost himself would attack the Chateau. Drake, commanded by Peter Naumoff would take up position between the chateau and La Presbytere Farm, where it was believed a company of Germans would be stationed. On the photo their route of advance is marked under the general name of “Hardy”

Rodney, commanded by John Timothy would protect the raiders from attack from the landward side. They would be stationed midway between the Chateay and Rendezvous point.

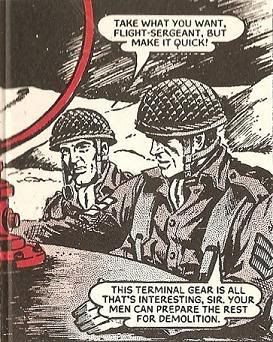

It was recognised that it may not be possible to remove all of the radar set due to time restrictions, so specific instructions were given as to which parts of the set would prove useful. The aerial from the centre of the bowl would help to prove the whether this set was responsible for the 570 transmissions. The receiver and presentation (display) equipment would reveal if the set included any anti-jamming device. Capture of the transmitter would give some idea of how well the set performed at the 570 level. It would also help if prisoners could be taken, especially a radar operator for information. Lastly if any equipment was impossible to move the engineers were to rip off any labels on that piece.

It was believed that the engineers would have less than 30 minutes with the set in which to carry out these tasks, so they were given a British gun laying radar to practice on and instructed to take photos or sketches of the German set if practical. After the half an hour was up Frost would withdraw back to the beach and his force would be collected by landing craft for the return trip to England. The beach to be used is next to where the Villa Stella Maris is marked on the photograph. You can see clearly to the left of this the high cliffs that made a sea borne commando assault impractical.

Planning came to a close with a final evacuation exercise taking place on the night of the 23rd February near Southampton Water. Tide conditions for evacuation and a full moon requirement meant that the raid would have to take place within 4 days or a delay of a month would be incurred. Bad weather for the next three days frustrated the allies, but on the 27th visibility was reasonable and the winds had dropped, so despite it having snowed that day the operation was given the green light.

The Raid

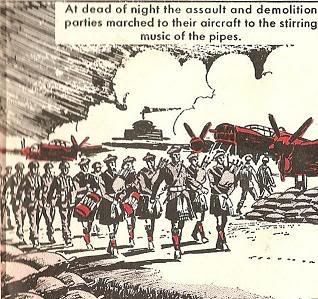

If you were standing at Throxton Airfield in the evening of the 27th February 1942 you would have seen an unusual sight. Frost’s men boarded their Whitley planes to the strains of Scottish pipe music, but since many of the men (including Frost) had been in Scottish regiments before joining the Paratroopers the sounds may well have been heartening. The flight was cold and just over two hours long, but with the issue of rum-laced tea not too uncomfortable. As the planes approached the French coast however they came under fire from coastal batteries. Two of them were driven off course by the fire, something that would cause problems later. Despite this the other 10 planes arrived over the right area and made the drop without any problems. Frost had managed to collect around 100 men at the rendezvous without any serious injuries. One thing not mentioned in the Victor story however is that one of the first things the men did was to answer the call of nature! All that tea drunk at Throxton and on the plane had taken its toll after all.

Although most of his command had arrived safely a large part of Nelson including Chatteris himself had been in the two Whitleys driven off course. Frost elected to continue regardless and his men soon moved off towards their objectives. Young’s men soon arrived at the radar site to find it manned, but a short firefight soon took care of the crew, one of which was captured (after he fell off the cliff trying to run away but was saved by a projecting rock!). Frost’s men quickly surrounded the Chateau then stormed inside. They only found 1 German on the upper floor who was firing on Young’s men around the radar who they promptly killed. Frost then left two sentries in the Chateau and moved the remainder of his men to join with Naumoff’s in protecting the radar site from the expected counter attack.

In the meantime the engineers had made one attempt to photograph the radar only to discover that this brought a great deal of unwanted attention their way. Giving this up they managed to saw off the aerial element but attempts to remove the other equipment proved elusive. Under fire they dropped any thought of being delicate and simply used crowbars to rip out the units. A hand trolley was brought up and loaded with the equipment but the enemy fire was increasing (one of the British dead fell here), the expected counter attack from La Presbytere was under way. Frost could soon hear vehicles moving in the distance and was concerned that the longer they waited the greater the chance the Germans would bring mortars to bear. He chose to withdraw, settling for whatever the engineers had managed to get so far and head for the beach.

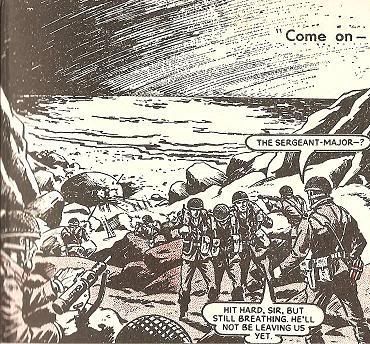

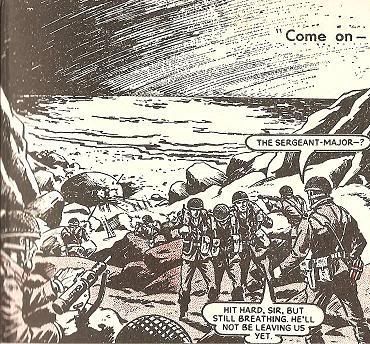

As his men headed straight for the beach they could hear firing from that direction, and as they passed close to a pillbox they came under fire themselves, wounding the Company Sergeant Major. Frost paused for a moment whilst he took in the situation and realised that Charteris’ men must still be missing, and the remainder of Nelson had been unable to achieve their objectives. He also discovered that Germans advancing from the Chateau area were threatening the rear of the column. This put Frost in a tricky position as the machine gun was pinning down his men, but he knew he would have to keep moving or risk missing the rendezvous. Fortunately for Frost the Germans from the chateau were advancing cautiously, giving him time to take stock of the situation.

Chatteris and his lost command meanwhile had been on a long march from his landing point, some 3 kilometres south of the intended drop zone. He immediately set off towards the sound of gunfire but found he had to shoot his way around Bruneval village, which was defended by a platoon of German infantry. Bypassing them he came up on the machine gun troubling Frost, quickly silenced it and moved on to seize the beach. Frost, realising that the troublesome gun was no longer firing advanced down to the beach and was relieved to find Charteris and the missing 20 men there, reuniting his command.

The time was about 2:15am, the British controlled the beach and Frost had completed almost all of his objectives. A signal was made to call in the naval assault craft, made all the more urgent as German forces were beginning to occupy the cliffs and fire down on the beach. Long minutes passed but the signallers received no reply, and another paratrooper was shot dead. In desperation green Verey lights were fired, but still no reply was given. Its easy to imagine how Frost and his men must have felt at this point, he may well have known about the Collosus raid and feared a repeat performance. Just as Frost prepared to return inland to create a better defence however the sound of the assault craft was heard, and relief flooded over the paratroopers.

Troops on board the boats provided covering fire as Frost ordered the withdrawal, beginning with the dismantling party and their precious cargo, then the prisoners and wounded and finally the remainder of his force. The assault craft then quickly withdrew and headed for home, covered shortly by Spitfires sent to protect the raiders. Frost later learnt that the reason for the delayed rescue had been that whilst he was signalling a German destroyer and two e-boats had passed within a mile of the British flotilla. Luckily they saw nothing, but they did prevent the ships from replying for those long minutes.

This photograph shows a party of paratroopers on one of the landing craft on their way back home. Major Frost stands on the bridge, second from the left.

Conclusion

Frost achieved virtually everything he had been ordered to, so the mission proved a great success. The dismantling party had returned with the receiver, the receiver amplifier, the modulator and transmitter, not to mention the sawn off aerial element. Only the presentation equipment had been left behind due to lack of time. From these pieces scientists were able to determine where the set had been manufactured, that it had no anti-jamming system (but it could be turned over a wide range making jamming harder) and that its design was relatively straightforward. The raid also confirmed beyond doubt that the Bruneval site was the origin of the 570 transmissions.

Frost had also captured two prisoners, one of who turned out to be a radar operator who had a bizarre theory as to what prompted the raid. A month earlier he had been on leave and happened to mention to his wife that the Bruneval site was so exposed that the British could easily make a raid and capture it. He wondered whether his wife was a British spy? This perhaps says more about the state of his marriage than anything else! All this had been achieved for the loss of two dead, six wounded and six missing (all of which were captured). In the raid’s aftermath the Germans methodically surrounded all costal radar sites with barbed wire entanglements, helpfully confirming to the British suspected sites.

Perhaps more than all of this however the raid had confirmed that airborne operations were a viable way of striking a blow at Hitler’s "Fortress Europe". Frost would go on from here to command 2nd Battalion in tight spots such as Tunisia, Sicily and of course Arnhem Bridge. Such an illustrious history came at a cost, and by the war’s end only 8 members of “C” company that had attacked the radar station had survived.

Sources:

After the Battle Issue 13 - Edited by Winston G Ramsey

Elite Series Volume 6, Article "Bruneval Raiders" by Major General John Frost

British Airborne Troops - Barry Gregory

Victor Annual 1969

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Biting

Why Bruneval?

When I was young my relatives would buy me an annual for Christmas. This usually involved “boy’s own” style comic stories about war, sporting prowess or superheroes. As I grew up I collected other annuals in a similar theme, including many from the years before I was born. A Victor annual from 1969 contained a story about a raid on the radar station at Bruneval (known as Operation Biting) that caught my attention since it described the an early operation carried out by British Paratroopers. I was also interested to notice that the British commander was a man familiar to me from reading about of the Market Garden Campaign, Major John Frost.

Information on the raid was difficult to locate at the time because I didn’t have access to the Internet, so it was many years before I managed to get more information. Within a short space of time I acquired an “after the battle” magazine containing an article on the raid, an article written by Frost many years after the war and a book on British paratroopers which had a brief section on the operation. I found that the real story was every bit as interesting as any comic book tale, and hopefully you will too.

A typical panel of the Victor story complete with an interesting take on how RAF pilots spoke during the war!

Historical Background to the raid

By late 1941 the British had been aware for some time that the Germans had been operating an early warning radar system known as Freya on the coast, which ran at 125 megacycles. A mystery had arisen however because signals had been recently received at 570 megacycles, suggesting a new system was being used. By this time the Directory of Intelligence at the Air Ministry had located a probable 27 sites for Freya from Bodo in Norway to Bordeaux in France. The origin of the 570 megacyle signal could be any one of these sites, and obviously it would be impossible to destroy all of them permanently.

Faced with this thorny problem Dr. Charles Frank a physicist who worked at the Directorate began to study the sites to try to determine any anomalies. When he looked at medium level reconnaissance of the Bruneval Site (located on the North Coast of France near Le Harve) he noticed something very strange. The site was located very close to high cliffs, with the Freya aerials located a short distance from a large building and connected to it by a path. The photos that Frank was studying however showed a large black object located midway between the cliff edge and the house, with a path connecting the two. It could be that the object was merely part of the Freya system, or it could be the elusive origin of the new signals, the Wurzburg system.

A few days after Frank’s discovery Flight Lieutenant Tony Hill paid a visit to the photo interpretation centre in Medmenham. He had been involved in numerous low level photo missions over the 27 radar stations, and the centre’s commander, aware of Frank’s interest mentioned the object to Hill. Not waiting for orders Hill decided to take off the next day and flew in low over the site and managed to get back out again before any of the Germans realised he was there. Upon returning however he discovered that his camera had failed! He was able to confirm however that the object appeared to be like “an electric bowl fire about 10 feet across”. If correct he had almost certainly found the elusive origin of the 570 transmissions.

Victor’s attempt to portray Hill’s flight got the plane wrong, he actually flew a Spitfire photo reconnaissance plane.

Despite the risks Hill repeated the feat the very next day, and this time returned with a photo of the site that confirmed everything he had said. This did not however prove beyond doubt that the radar transmitted on 570 megacycles, and until then nothing could be done to counter it. It was at this point that a raid was considered to snatch the system and as much information on it as possible. Commandos were ruled out almost immediately as the Bruneval site lay at the top of high cliffs, and was heavily defended. At this point it was suggested by Lord Louis Mountbatten that Paratroopers could be used for the raid. It was a bold suggestion since for the British this was a virtually untried form of warfare.

Hill’s famous photograph from his second flight. Its perhaps worth noting that the clarity of the photo worried the paratroopers who felt that Hill must have flown so low that the Germans would guess a raid was imminent.

Origins of Britain’s Paratroopers

Parachute troops were a relatively new development in warfare but as the Germans had so recently demonstrated in Crete, Corinth, the Low Countries and Norway they certainly had their value when employed correctly. The British began to experiment in the field after the fall of France in 1940 with Churchill ordering the formation of a 5,000 strong force with the aim of taking the war back to the continent in small scale raids. Based out of Ringway airbase in Manchester (which later became the city’s international airport) training began as early as the July 1940 using 6 Whitley bombers as transport craft. Real progress was slow however and opposition high, especially in the ranks of the RAF. They felt it was frittering away their precious resources that could be better employed on the defence of the home islands and strategic bombing. These first units still operated under the title of commandos but were soon reformed as wings of the No 11 Special Air Service Battallion. This formation is not to be confused with the more famous SAS regiment founded by David Stirling, as they were separate formations.

Despite lack of resources training tried to be as accurate as possible and reflect the fortunes of war.

The first test of No 11 SAS was a raid to destroy the Tragino aqueduct in southern Italy. Around two million inhabitants of the surrounding area relied on the aqueduct to provide water, and it was felt that destroying it would create panic and damage the Italian war effort. Forty officers and men took part in the raid, which was launched from Malta, landing the raiders at night within a short distance of the target. The raiders were able to destroy the aqueduct without much trouble, also succeeding in destroying a nearby bridge to hinder the reaction of any local police troops. The raiders then split up in order to make their way to the coast but unknown to them the submarine assigned to pick them up had been ordered not to sail. One of the Whitley’s assigned to provide a diversionary raid suffered engine problems and radioed that it was forced down almost right on top of the pick-up spot, causing fears that the pick-up would be compromised.

Every single one of the raiders were captured over the next few days, and one of the Italian interpreters (who was an anti-fascist) attached to the raid was shot by local militia. Whilst Colossus provided mixed results it did prove that it was practical to drop parachute troops into enemy controlled county at night. Knowing this was crucial to the decision to employ paratroopers for the Bruneval raid as that would require a night assault. By this time the original 11 SAS had been reformed as the 1st Parachute Battalion, part of the newly raised 1st Parachute Brigade which was due to be part of Britain’s first parachute division to be commanded by Major General F.A.M Browning.

Planning for the raid

Having established that the raid would be conducted by parachute troops the task was assigned to Major John Frost’s “C” company of the 2nd Parachute Battalion. Also attached would be a team of 7 men from the Royal Engineers and Flight Sergeant Cox, a RAF radar operator. Frost planned to drop a short distance inland from the target and after forming up split into 3 main groups. Some of what I will describe next can be seen on the scanned photo below which I appreciate is not great quality, but hopefully will be sufficient visual aid to the action described.

Nelson, commanded by Lieutenant Charteris would move directly towards the beach and secure it. On the way he would be expected to clear the cliffs near the beach and move into Bruneval Village (the edge of which is barely in photo at the bottom right). Note that the “route to beach” marker on the photo indicates the route Frost and the main force used, and is not an indication of Chatteris’ intended route.

The next force was allocated to making the main attack towards the radar so split further into three groups. Jellicoe under Peter Young was to move straight to the radar installation and secure it for the Royal Engineers to move in and complete their work. Hardy group, which was commanded by Frost himself would attack the Chateau. Drake, commanded by Peter Naumoff would take up position between the chateau and La Presbytere Farm, where it was believed a company of Germans would be stationed. On the photo their route of advance is marked under the general name of “Hardy”

Rodney, commanded by John Timothy would protect the raiders from attack from the landward side. They would be stationed midway between the Chateay and Rendezvous point.

It was recognised that it may not be possible to remove all of the radar set due to time restrictions, so specific instructions were given as to which parts of the set would prove useful. The aerial from the centre of the bowl would help to prove the whether this set was responsible for the 570 transmissions. The receiver and presentation (display) equipment would reveal if the set included any anti-jamming device. Capture of the transmitter would give some idea of how well the set performed at the 570 level. It would also help if prisoners could be taken, especially a radar operator for information. Lastly if any equipment was impossible to move the engineers were to rip off any labels on that piece.

It was believed that the engineers would have less than 30 minutes with the set in which to carry out these tasks, so they were given a British gun laying radar to practice on and instructed to take photos or sketches of the German set if practical. After the half an hour was up Frost would withdraw back to the beach and his force would be collected by landing craft for the return trip to England. The beach to be used is next to where the Villa Stella Maris is marked on the photograph. You can see clearly to the left of this the high cliffs that made a sea borne commando assault impractical.

Planning came to a close with a final evacuation exercise taking place on the night of the 23rd February near Southampton Water. Tide conditions for evacuation and a full moon requirement meant that the raid would have to take place within 4 days or a delay of a month would be incurred. Bad weather for the next three days frustrated the allies, but on the 27th visibility was reasonable and the winds had dropped, so despite it having snowed that day the operation was given the green light.

The Raid

If you were standing at Throxton Airfield in the evening of the 27th February 1942 you would have seen an unusual sight. Frost’s men boarded their Whitley planes to the strains of Scottish pipe music, but since many of the men (including Frost) had been in Scottish regiments before joining the Paratroopers the sounds may well have been heartening. The flight was cold and just over two hours long, but with the issue of rum-laced tea not too uncomfortable. As the planes approached the French coast however they came under fire from coastal batteries. Two of them were driven off course by the fire, something that would cause problems later. Despite this the other 10 planes arrived over the right area and made the drop without any problems. Frost had managed to collect around 100 men at the rendezvous without any serious injuries. One thing not mentioned in the Victor story however is that one of the first things the men did was to answer the call of nature! All that tea drunk at Throxton and on the plane had taken its toll after all.

Although most of his command had arrived safely a large part of Nelson including Chatteris himself had been in the two Whitleys driven off course. Frost elected to continue regardless and his men soon moved off towards their objectives. Young’s men soon arrived at the radar site to find it manned, but a short firefight soon took care of the crew, one of which was captured (after he fell off the cliff trying to run away but was saved by a projecting rock!). Frost’s men quickly surrounded the Chateau then stormed inside. They only found 1 German on the upper floor who was firing on Young’s men around the radar who they promptly killed. Frost then left two sentries in the Chateau and moved the remainder of his men to join with Naumoff’s in protecting the radar site from the expected counter attack.

In the meantime the engineers had made one attempt to photograph the radar only to discover that this brought a great deal of unwanted attention their way. Giving this up they managed to saw off the aerial element but attempts to remove the other equipment proved elusive. Under fire they dropped any thought of being delicate and simply used crowbars to rip out the units. A hand trolley was brought up and loaded with the equipment but the enemy fire was increasing (one of the British dead fell here), the expected counter attack from La Presbytere was under way. Frost could soon hear vehicles moving in the distance and was concerned that the longer they waited the greater the chance the Germans would bring mortars to bear. He chose to withdraw, settling for whatever the engineers had managed to get so far and head for the beach.

As his men headed straight for the beach they could hear firing from that direction, and as they passed close to a pillbox they came under fire themselves, wounding the Company Sergeant Major. Frost paused for a moment whilst he took in the situation and realised that Charteris’ men must still be missing, and the remainder of Nelson had been unable to achieve their objectives. He also discovered that Germans advancing from the Chateau area were threatening the rear of the column. This put Frost in a tricky position as the machine gun was pinning down his men, but he knew he would have to keep moving or risk missing the rendezvous. Fortunately for Frost the Germans from the chateau were advancing cautiously, giving him time to take stock of the situation.

Chatteris and his lost command meanwhile had been on a long march from his landing point, some 3 kilometres south of the intended drop zone. He immediately set off towards the sound of gunfire but found he had to shoot his way around Bruneval village, which was defended by a platoon of German infantry. Bypassing them he came up on the machine gun troubling Frost, quickly silenced it and moved on to seize the beach. Frost, realising that the troublesome gun was no longer firing advanced down to the beach and was relieved to find Charteris and the missing 20 men there, reuniting his command.

The time was about 2:15am, the British controlled the beach and Frost had completed almost all of his objectives. A signal was made to call in the naval assault craft, made all the more urgent as German forces were beginning to occupy the cliffs and fire down on the beach. Long minutes passed but the signallers received no reply, and another paratrooper was shot dead. In desperation green Verey lights were fired, but still no reply was given. Its easy to imagine how Frost and his men must have felt at this point, he may well have known about the Collosus raid and feared a repeat performance. Just as Frost prepared to return inland to create a better defence however the sound of the assault craft was heard, and relief flooded over the paratroopers.

Troops on board the boats provided covering fire as Frost ordered the withdrawal, beginning with the dismantling party and their precious cargo, then the prisoners and wounded and finally the remainder of his force. The assault craft then quickly withdrew and headed for home, covered shortly by Spitfires sent to protect the raiders. Frost later learnt that the reason for the delayed rescue had been that whilst he was signalling a German destroyer and two e-boats had passed within a mile of the British flotilla. Luckily they saw nothing, but they did prevent the ships from replying for those long minutes.

This photograph shows a party of paratroopers on one of the landing craft on their way back home. Major Frost stands on the bridge, second from the left.

Conclusion

Frost achieved virtually everything he had been ordered to, so the mission proved a great success. The dismantling party had returned with the receiver, the receiver amplifier, the modulator and transmitter, not to mention the sawn off aerial element. Only the presentation equipment had been left behind due to lack of time. From these pieces scientists were able to determine where the set had been manufactured, that it had no anti-jamming system (but it could be turned over a wide range making jamming harder) and that its design was relatively straightforward. The raid also confirmed beyond doubt that the Bruneval site was the origin of the 570 transmissions.

Frost had also captured two prisoners, one of who turned out to be a radar operator who had a bizarre theory as to what prompted the raid. A month earlier he had been on leave and happened to mention to his wife that the Bruneval site was so exposed that the British could easily make a raid and capture it. He wondered whether his wife was a British spy? This perhaps says more about the state of his marriage than anything else! All this had been achieved for the loss of two dead, six wounded and six missing (all of which were captured). In the raid’s aftermath the Germans methodically surrounded all costal radar sites with barbed wire entanglements, helpfully confirming to the British suspected sites.

Perhaps more than all of this however the raid had confirmed that airborne operations were a viable way of striking a blow at Hitler’s "Fortress Europe". Frost would go on from here to command 2nd Battalion in tight spots such as Tunisia, Sicily and of course Arnhem Bridge. Such an illustrious history came at a cost, and by the war’s end only 8 members of “C” company that had attacked the radar station had survived.

Sources:

After the Battle Issue 13 - Edited by Winston G Ramsey

Elite Series Volume 6, Article "Bruneval Raiders" by Major General John Frost

British Airborne Troops - Barry Gregory

Victor Annual 1969

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Biting