Human trials of artificial wombs could start soon

A hairless, pale-skinned lamb lies on its side in what appears to be an oversized sandwich bag filled with hazy fluid. Its eyes are closed, and its snout and limbs jerk as if the animal — which is only about three-quarters of the way through its gestation period — is dreaming.

The lamb was one of eight in a 2017 artificial-womb experiment carried out by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) in Pennsylvania. When the team published its research1 in April of that year, it released a video of the experiments that spread widely and captured imaginations — for some, evoking science-fiction fantasies of humans being conceived and grown entirely in a laboratory.

Now, the researchers at CHOP are seeking approval for the first human clinical trials of the device they’ve been testing, named the Extra-uterine Environment for Newborn Development, or EXTEND. The team has emphasized that the technology is not intended — or able — to support development from conception to birth. Instead, the scientists hope that simulating some elements of a natural womb will increase survival and improve outcomes for extremely premature babies. In humans, that’s anything earlier than 28 weeks of gestation — less than 70% of the way to full term, which is typically between 37 and 40 weeks.

The CHOP group has made bold predictions about the technology’s potential. In another 2017 video describing the project, Alan Flake, a fetal surgeon at CHOP who has been leading the effort, said: “If it’s as successful as we think it can be, ultimately, the majority of pregnancies that are predicted at-risk for extreme prematurity would be delivered early onto our system rather than being delivered premature onto a ventilator.” In 2019, several members of the CHOP team joined a start-up company, Vitara Biomedical in Philadelphia, which has since raised US$100 million to develop EXTEND. (Flake declined to comment for this article, citing “conflicts of interest” and “restrictions on proprietary information”. His co-authors on the 2017 paper did not respond to Nature’s request for comment.)

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will convene a meeting of independent advisers on 19–20 September to discuss regulatory and ethical considerations and what human trials for the technology might look like. The committee’s discussion will be scrutinized by the handful of other groups around the world that are developing similar devices, and by bioethicists exploring the implications for health equity, reproductive rights and more.

“This is definitely an exciting step and it’s been a long time coming,” says Kelly Werner, a bioethicist and neonatologist at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City, who is not affiliated with groups developing artificial-womb technology. “Clinicians who work with premature babies will be closely following this meeting,” she says.

Early start

Preterm birth, defined by the World Health Organization as birth before 37 weeks of gestation, can happen spontaneously or because some conditions — such as an infection, hormone imbalance, high blood pressure or diabetes — can turn the womb into an inhospitable environment for the fetus.

It poses an enormous global health problem. Preterm birth is the largest cause of death and disability in children under five. In 2020, there were about 13.4 million such births worldwide, and complications related to preterm birth caused about 900,000 deaths in 2019.

Mortality is strongly linked with the baby’s gestational age at birth. At or before 22 weeks — considered the cusp of fetal viability — few fetuses survive outside the womb. By 28 weeks, most can survive, but often require significant life support. Artificial-womb technology aims to improve outcomes for preterm babies who are born in the period between 22 and 28 weeks, for whom survival has improved, but long-term health issues are frequent.

In a study2 of 2.5 million people in Sweden, for example, 78% of people born before 28 weeks of gestation had some sort of medical condition — ranging from asthma and hypertension to cerebral palsy and epilepsy — by the time they were adults. For full-term births, that rate was 37%.

Death and disability, especially in babies born at younger gestational ages, often occur because the lungs and brain are among the last organs to fully mature in humans. That’s why obstetricians try to prevent preterm birth whenever possible — the longer fetuses can safely stay in the womb, the higher their odds are of long-term survival and good health.

In a natural womb, a fetus receives oxygen, nutrients, antibodies and hormonal signals and gets rid of waste through the placenta, a transient organ in which fetal blood interacts with maternal blood. Of these various roles, artificial-womb technology is most focused on providing oxygen and removing carbon dioxide, replacing the mechanical ventilators that are often used for neonates. These can damage fragile developing lungs that would otherwise still be filled with amniotic fluid.

The artificial womb “would bridge a baby born extremely premature through those days and weeks when they’re most at risk for lung and brain damage”, Werner says. The CHOP group has signalled that it would wean babies off its system after a few weeks, when their organs are more fully developed and their likelihood of healthy survival is higher.

The group’s system would work by placing extremely premature babies into what it calls a Biobag, filled with an electrolyte-laden fluid designed to mimic amniotic fluid. Surgeons would connect the blood vessels in the umbilical cord to a system that oxygenates blood outside the body. The fetal heart would still pump blood as it does in the natural womb.

Making the connection with blood vessels in the umbilical cord is difficult, because the arteries are tiny and begin to contract as a baby is delivered. So, surgeons will need to hook up the vessels to the system within minutes. The process “has got to be really slick”, requiring deft surgical skills and speedy transitions, says Anna David, a maternal–fetal specialist at University College London.

Flake and his colleagues have been testing the system on lambs, which are often used in fetal research because they are developmentally similar to humans. Sheep typically gestate for about 5 months; the lambs that the researchers used were the equivalent of a human fetus at 23 weeks of gestation. In 2017, the team reported that it kept eight lambs alive for up to four weeks using the artificial womb1. In that time, the animals sprouted wool and their lungs and brains grew to maturity. After four weeks, the researchers euthanized the animals so they could study how the system had affected organ development.

Since 2017, the researchers have been testing various ways to connect the animals to the oxygenation machine, and they have been in conversation with the FDA about starting clinical trials.

Varying approaches

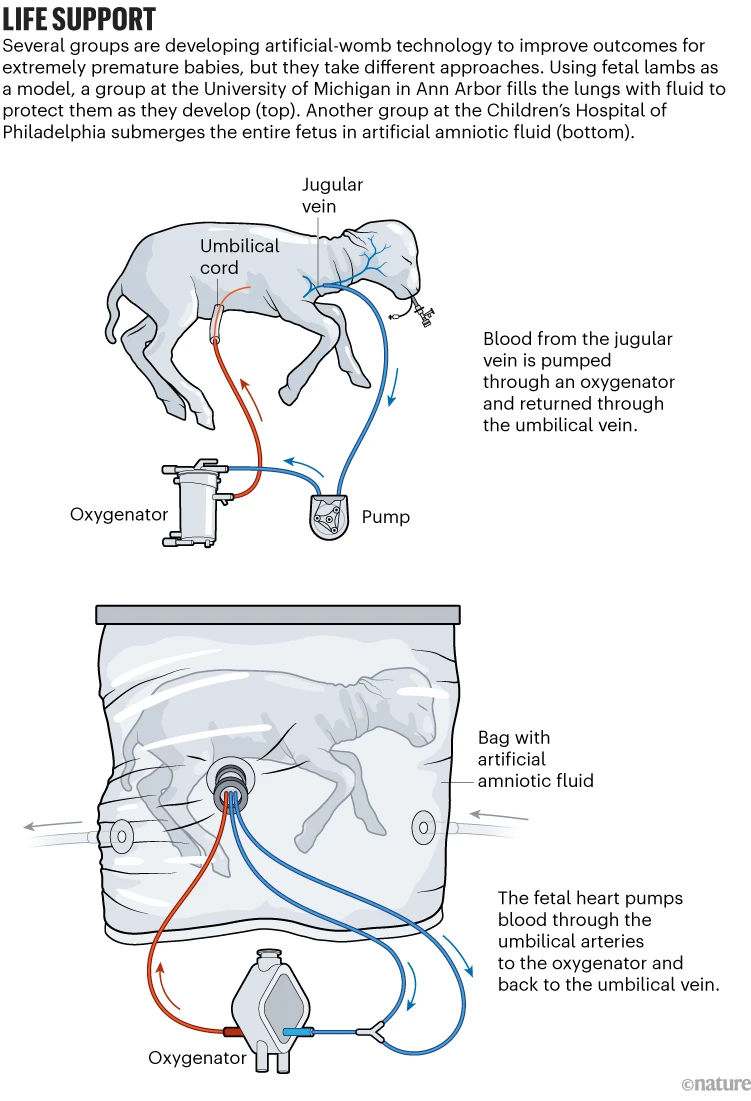

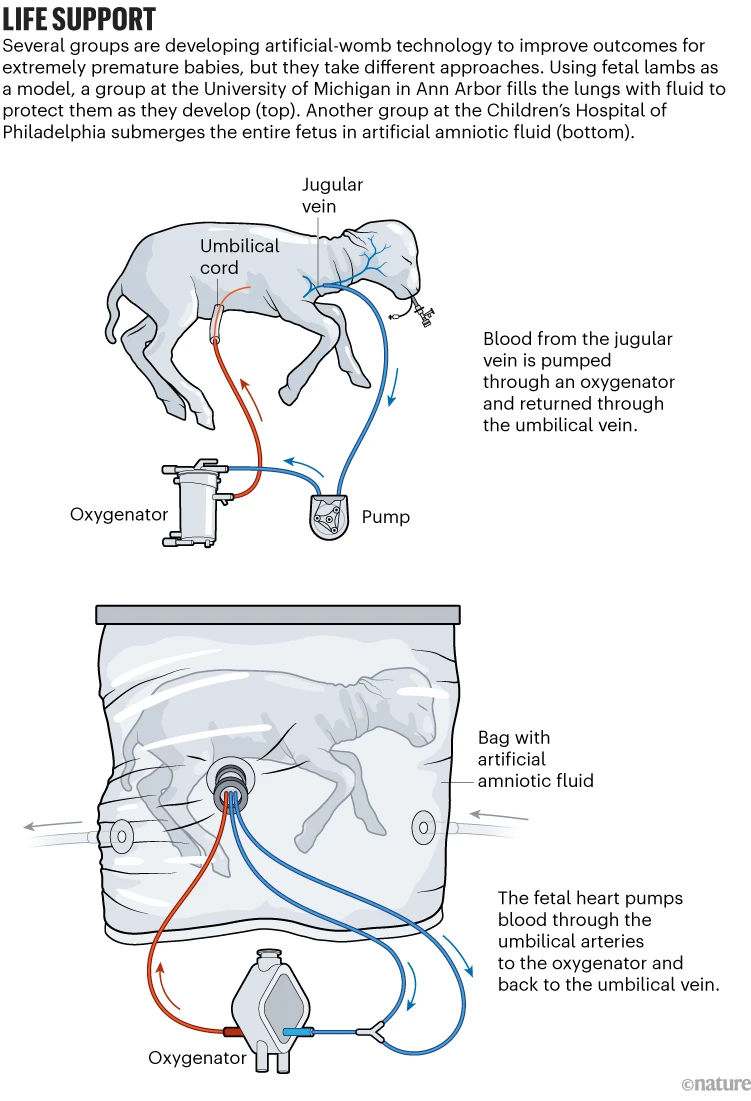

Researchers who spoke to Nature say that the CHOP group’s system is probably closest to human trials. But groups in Spain, Japan, Australia, Singapore and the Netherlands are also developing artificial-womb technology. A team led by fetal surgeon George Mychaliska at University of Michigan Health in Ann Arbor refers to its device as an artificial placenta. And even though in practice it serves the same purpose as EXTEND, the teams’ approaches are starkly different (see ‘Life support’).

The Michigan device doesn’t surround babies with fluid, but instead fills only their lungs though an endotracheal tube. And it uses a pump to draw blood from the jugular vein, oxygenate it outside the body and send it back in through the umbilical vein; the CHOP group hooks its device up to both the umbilical arteries and the vein.

Each approach comes with its own pros and cons, which the groups highlighted in a pair of commentaries in July3,4. Currently, the CHOP device necessitates delivery by caesarean section, because the umbilical arteries start closing quickly during birth, and natural labour can take a long time. But the risks of an elective c-section for a pregnant person are not trivial and must be factored in to the equation, David says. In its July article3, the CHOP group acknowledges this risk, but notes that up to 55% of extremely premature babies are already born by c-section.

By contrast, clinicians using Michigan’s approach could deliver a premature baby naturally and determine whether the infant can breathe unaided. If not, they could still hook it up to the system, because the umbilical vein doesn’t close as quickly as the arteries do, says Robert Bartlett, a surgeon at the University of Michigan who works with Mychaliska. But the external pump for moving blood around carries a risk of straining the heart or causing brain bleeds. According to published data, the Michigan group has so far sustained lambs for about two weeks5, compared with the CHOP group’s four weeks. (Mychaliska did not respond to e-mails asking for comment.)

Although the groups disagree on the best approach, Bartlett says he hopes the CHOP group successfully secures FDA approval for human trials. He and his colleagues at Michigan plan to seek FDA approval in about a year, he adds.

Eduard Gratacós, a fetal-medicine specialist at the University of Barcelona in Spain who is also developing an artificial womb, acknowledges that his group is years behind the CHOP group. But if clinical-trial results look promising, he says, “we’re going to need several of these systems in the world”.

A leap from lambs

Even as excitement mounts about this type of technology, however, questions remain about what data will be required to get the green light for human trials. “It’s a big leap to go to humans from lambs,” Gratacós says.

Lambs at the same stage of development as extremely premature babies are two to three times larger, meaning that researchers would need to further tweak the already-tiny equipment necessary for the artificial womb. Fetal pigs are more similar in size to human fetuses, but they are harder to work with than lambs, Bartlett says. Non-human primates are a gold-standard animal model to precede clinical trials because of their physiological similarities to humans, but their fetuses are even smaller than those of humans, and the ethics of conducting such experiments are complex.

Guid Oei, an obstetrician at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, and his colleagues have been developing their own artificial-womb system alongside simulation dolls that allow clinicians to practice transferring a fetus. “You only have one chance to do it right, and the learning curve should not be on actual human beings,” he says.

Nevertheless, to Matthew Kemp, an obstetrician at the National University of Singapore, “the data aren’t there from an ethical position” to justify the launch of human trials, unless “someone is sitting on a bunch of data that isn’t published”. Kemp, who is also developing an artificial-womb system, hopes to see data on how the experimental animals fare in the long term, as well as data from non-human primates, before clinical trials begin. (The CHOP group hinted at “extensive unpublished data prepared for regulatory approval” in its July commentary3.) “It’s a new treatment modality,” Kemp says. “The bottom line is they’ve got to make a really strong case that it’s better and safer in the short and long term” than the current life-saving measures used.

Ethics and more

Safety questions won’t be the only ethical concerns. The development of artificial wombs represents a “big transformational leap” that “solves lots of issues”, says David. But, she adds, “it also opens up a whole new slew of issues”. After the 2017 study1 generated extensive media coverage, fears spread that artificial wombs could one day replace pregnancy.

But researchers discount these concerns. This idea “is so far in the distant future that it’s not worth discussing its implications in relation to the current technology”, Werner says.

Those developing artificial wombs in the United States will also have to contend with a politically charged environment for reproductive rights. Flake and Mychaliska have been careful not to give any indication that an artificial womb could change the definition of fetal viability — which has enormous implications after the US Supreme Court struck down the 1973 landmark abortion decision Roe v. Wade in June last year. Previously, the 1973 ruling had protected abortion until the fetus is viable outside the womb.

Even what to call the entities in these devices is fraught, says Chloe Romanis, a biolawyer at Durham Law School, UK. They’re not fetuses in the conventional sense because they are no longer in the womb, she says. And some argue that they are not neonates, which, by the Latin root of the word, assumes they’ve been born. “The name we give to these new unprecedented patients has implications for rights that the law and society affords,” Werner says. The CHOP group has proposed a new name altogether: fetal neonates, or fetonates for short.

Some researchers also worry that artificial wombs would represent an expensive technological solution to a deeper problem. Michael Harrison, a fetal surgeon at the University of California, San Francisco, sometimes called the ‘father of fetal surgery’, says the data he has seen so far have been promising. But he questions whether it’s worth “throwing all that money and tech” on babies that have a poor likelihood of survival instead of finding ways to improve pregnancy support or standard techniques for preterm critical care, which could reduce the need for artificial-womb technology in the long run.

David agrees, adding that there is insufficient research and funding to understand why women go into labour early and how to prevent it. “We need to get real with this,” she says. “Artificial wombs will impact only a tiny fraction of the problem.”

Bartlett says that systemic measures are important, but he argues that better treatment is urgently needed for extremely preterm babies. “A silver bullet that prevents prematurity doesn’t exist and is unlikely to exist in our lifetimes,” he says. “These technologies are what we need when the systemic measures fail.”