The 170 year period starting in 190AD was the first where the French came under significant military pressure. The line between victory and defeat was extremely narrow, as the Mayans made a continued push towards Bailli, and the Sumerians made their first attacks, leading to the loss of the Armée Épéistes V during the battle of Hangchow in 290AD.

At the end of the year 190AD, there were 12 enemy divisions inside French territory. At the high point of enemy incursions in 310AD, there were no less than 27 enemy units inside French territory, and 37 just outside the French borders. At the end of 360AD, only 10 enemy divisions remained inside French territory. A total of 156 enemy divisions were decimated during this period, more than half of them during the latter 60 years. The French lost only one tenth of that number. Military records show that the French had 87 military units in the field at the end of 360AD, 17 of them in the 5 active armies.

Discoveries and technological advancement

Around this time, the French knew about 7% of the world. They continued to explore the lands surrounding them, mostly to determine where their enemies' vulnerabilities lay. The Lanciers de Gaulle were sent on an expedition towards the Egyptians, and discovered gems in the northern mountains. The brave spearman division was ultimately killed in 290AD when they ventured too close to the Egyptian town of Pi-Ramesses.

The French scientists continued their research, and discovered the secrets of Map Making, Polytheism and Currency.

With the development op Map Making, the French started maintaining detailed maps of their territory and of their military campaigns. The Bailli Encirclement is a prime example of a campaign for which a set of such maps was created.

The other civilizations were technologically more advanced at that time. Only the Greeks and the Koreans weren't much ahead in knowledge, compared to the French. Most civilizations were bent on constructing Wonders of the World to demonstrate their knowledge and power. In 260AD, Rome built Sun Tzu's Art of War, and the Incan city of Tiwaniku finished the Great Lighthouse. In 360AD, the Mayans built Leonardo's Workshop in Tikal.

Territorial expansion

During this period, four new French towns were settled. Deux Chevaux was founded in 210AD to gain control of a second source of horses. Little agricultural activity could be developed there, so it became a home for scientists.

[size=-2]View of the north of France in 210AD. Deux Chevaux was founded deep in the Chaîne des Loups.[/size]

In 300AD, Bananes was founded to complete the Bailli encirclement

.

[size=-2]View of the northwest of France in 300AD. Enemy incursions were at its height at this time, with an

especially large contingent of Mayan troops. All those troops would soon meet their demise.[/size]

On the Aztec border, Cité Interdite was founded in 310AD, and would become home of the Forbidden Palace.

[size=-2]View of the south of France in 310AD. La Cité Interdite would become the staging area for the attack on the Aztec heartland.[/size]

Clermont-Ferrand was founded in 340AD, sealing off the northern border.

[size=-2]View of the north of France in 340AD. At the left of the map, you can see that

irrigation had been brought to Défaite (and Calé-en-Desert) by this time.[/size]

The Koreans founded Manp'o in the northern tundra, finally prompting a reaction from the French. The Armée Épéistes VI was dispatched to take the two Korean towns in the north.

[size=-2]View of the north of France in 360AD. At the top left of the map, the location of

gems deposits has been marked. The army was approaching via the iron and furs road.[/size]

Economy

Slavery was introduced in French society in 340AD, when the first foreign settler was captured, trying to move through French lands. By 360AD, 6000 slaves of Aztec, Persian and Sumerian descent were laboring in the mines of Charleville. Many more slaves would be captured by the French, which would help to further develop the economy. As the French empire grew, the need for laborers would only increase.

The construction of the Forbidden Palace in 350AD resulted in a further increase of commerce and production, especially in nearby towns. Historical records show that the French carefully planned the founding of additional towns, to increase the productive and commercial capacity of the empire, as well as the ability to support the ever growing military.

Even though the French had been under constant attack for thousands of years, they had succeeded in building a relatively sound economy. In the table to the right, you can see that the French empire ranked reasonably well compared to the other civilizations. Commercial output would soon grow, as several harbors would be built, as well as marketplaces. The French population was growing rapidly, and was already at a respectable level.

Military

Military action continued in four more or less separate arenas. From south to north, there were

- The Tlaxcala arena

- The Hangchow arena

- The Soies-Bailli arena

- The Gaulle arena

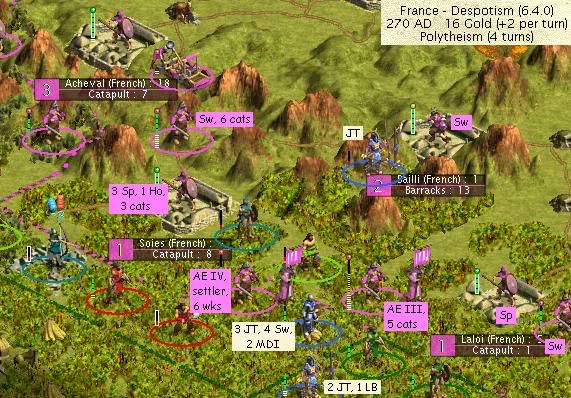

These four areas are highlighted in the illustration below, with main troop movements indicated with arrows. Each enemy civilization mostly focused on a single area, or two adjacent areas at most.

[size=-2]View of the French front at the beginning of 310AD, at the high point of enemy incursions. Around that time,

35 enemy divisions were within French territory, and about the same number just outside French borders.

The four main battle arenas during this period have been highlighted.[/size]

The Tlaxcala arena

The region from Tlaxcala to Charleville was invaded mostly by Persian longbowmen and Chinese horsemen. The Aztecs either moved towards Charleville, or towards Hangchow. The French had set up defense in Tlaxcala, which served as the base of operations for close to a hundred catapults, a few spearman divisions, a few swordsmen, and of course the renowned Cavaliers de Tlaxcala, led by Propre De Gaulle.

[size=-2]View of the south of France and Tenochtitlan around 210AD. A French

army had been sent out to pillage infrastructure around the Aztec capital.[/size]

The complex logistics of fielding bigger armies on four fronts required a centralized command for the ever growing French military. Propre De Gaulle was instrumental in getting the Pentagon built in Quentin to that end.

At the same time, the French moved outside of their borders to disrupt the commercial and agricultural activity in the Aztec capital. By 250AD, Tenochtitlan was completely disconnected from the rest of the world. Even though the French had to pull back after that, the Aztecs had been dealt a serious economic blow. Tenochtitlan's population dropped from almost 400,000 to around 70,000 over the course of a hundred years.

As the focus of the enemy shifted, the Tlaxcalan soldiers would occasionally help out near Hangchow. In 260AD, the Lanciers de Tlaxcala fought a heroic battle to safeguard the road between Hangchow and Charleville, killing an entire division of Aztec archers and defending against Sumerian medieval infantry, but finally succumbing to a second wave of Sumerian attackers. Charlemagne managed to escape the Sumerians, and remained in exile until 290AD, when he took command of the Armée Épéistes VI to replace the army that was lost in the battle of Hangchow.

[size=-2]View of the Tlaxcala-Hangchow region in 260AD.[/size]

The Tlaxcala region proved the most easy to defend by the French, because the enemy units attacking there were weakest. That situation started to change in 360AD, when the first Persian immortals started to appear.

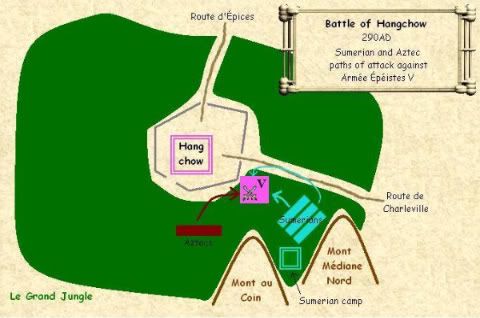

The Hangchow arena - Battle of Hangchow

The Sumerians first arrived in force around 170AD. They used Aztec roads south of Tenochtitlan to quickly move towards Hangchow, traveling through the southern Louvetaux, making it hard for the French to attack them before they arrived at the gates of Hangchow.

In 250AD, the third and fifth swordsman armies succeeded in killing 3 Sumerian swordsman divisions and 1 division of medieval infantry, but they were ultimately unable to avoid a direct attack on Hangchow. In 260AD, 5 more Sumerian divisions were slaughtered by the armies, aided by the Lanciers de Tlaxcala. The Aztecs joined in with medieval infantry as well, and the tide started to turn in favor of the attackers.

Still, by the year 280AD, the Hangchow area was clear of Sumerians and Aztecs. Only a few divisions had managed to escape. The French command decided to take advantage of this pause. The Armée Épéistes was moved north to provide protection for the settlers that were to found Bananes. All 80 catapults were moved towards Tlaxcala, to help provide cover for the settlers that were to found Cité Interdite. The Armée Épéistes V stayed behind in Hangchow, along with the elite Lanciers de Charleville and another corps of veteran spearmen.

But the continuous fighting had clearly taken its toll, and the army was caught completely by surprise by a Sumerian swordsman attack. The Sumerian attack was finally repelled, but a lone division of Aztec medieval infantry noticed that the army was depleted. They attacked the French from behind and slaughtered the 6,000 remaining swordsmen in the army.

Hangchow held, with the two spearmen divisions remaining. Those two divisions would continue to defend Hangchow against many attacks, mostly by superior units, until 360AD, when Hangchow's garrison was complemented with two divisions of swordsmen. Hangchow's walls had been completed in 290AD, right after the big battle, and catapults had been moved back into the town. Between 60,000 and 70,000 Aztec, Sumerian and Persian soldiers died as they attacked Hangchow during these 170 years. Many more died as the French continuously bombarded and attacked them while they were laying siege on the town.

The Soies-Bailli arena - The Bailli encirclement - Battles of Laloi

The heaviest fighting occurred in the triangle between Soies, Bailli and Laloi, where the Mayans pushed straight north towards Bailli. The French had inferior numbers, so they decided to fight a war of attrition. The Mayans were allowed to approach Bailli, where they were met with a barrage of catapult bombardment. As the Mayan divisions were depleted, they decided against attacking Bailli, which was a real stronghold with its high walls and its elevated position on the Collines de Bailli.

Instead, the Mayans retreated to treat their wounded, to just outside French territory, southeast of Soies. At first the French could not strike at the Mayans there, because there weren't any roads. But between 260AD and 300AD, French workers known as the "Travailleurs Routiers", under cover of several armies, constructed a road through the jungle connecting Laloi with Soies. In 300AD, the town of Bananes was founded and the Mayans were trapped behind enemy lines. A total of 23 Mayan divisions were suddenly cut off from their supply lines.

In a desperate move, they twice attacked Laloi, in 300AD and in 310AD, but the French suffered only minimal losses while completely destroying the Mayan forces. The remaining Mayans were killed off as they tried to make their way out of French territory. Between 120,000 and 130,000 Mayan soldiers died in the thick French jungle.

There were also minor skirmishes near Soies, as various enemy nations tried to disrupt the French silks operations. At one occasion in 340AD, another great leader emerged, who would help build the Forbidden Palace in Cité Interdite.

[size=-2]View of the northwest of France in 340AD. The effect of the Bailli Encirclement

can already be seen: practically no Mayan troops are left in French territory.[/size]

In 310AD and 350AD, two more leaders were appointed by the French command, after demonstrating their capabilities in combat near Laloi. Napoléon de Laloi took command of the Armée Épéistes VII, the fifth active swordsman army at the time. Propre De Gaulle helped constructing France's oldest marketplace, in Épices.

The Gaulle arena

The combat area in the north was by far the largest one. Especially the Egyptians appeared in unpredictable patterns. The French were able to keep Gaulle undefended for the most part, thus luring the Egyptian, Greek and Roman attackers towards that town. From the surrounding hills, the French could bombard and attack at their leisure.

The logistics for that area were far from trivial. Troops trained in Ancêtres and Défaite were moved in from the east, while catapults were dispatched from the west as needed and if the situation in the Soies-Bailli region allowed it.

See also