The Sound of Drums - A British Hearts of Iron II AAR

Part Forty-Nine

21st June - 1st September, 1940

Diplomatic endeavours of the British Empire

The battlefields of Europe provided the most dramatic and obvious conflicts of the past two months, but there was an altogether rather different engagement being conducted behind the scenes. Ever since Prime Minister Sharuminar had declared Britain would go it alone, he discovered that he couldnt. The diplomatic encounters since the fall of France proved that, not only was Britain dependant on others to aid them in the war effort, but some depended on Britain as the one bastion of hope in the free world.

Not that the French would agree. Within a week of the creation of Vichy France and the new French colonies, London was paid a visit by General Charles de Gualle. He had evacuated France with three divisions before the armistice, managing to make his way to still-loyal French Cameroon and declaring a Free French Army. Thousands more French soldiers made their way to him, and by September would form a grand force of seven Free French Divisions.

Charles de Gualle

Not that they could do much. Vichy France was still neutral, and without British approval the Allies would not go to war with them. If De Gualle had hoped his visit would convince the Prime Minister to launch a campaign against Vichy, he was dreadfully frustrated. Still reeling after the evacuation of France and only just beginning the fight against Italy, Kan Sharuminar refused to open another theatre of operations.

De Gaulle was hardly happy. The first period of talks between the two Allied leaders led to some heated arguments, with accusations of treachery and abandonment being sent the British Prime Ministers way. The second talks didnt go much better, with De Gualle suggesting that Free France would go it alone, leave the allies and fight its own campaign to whatever end. A wearied Kan Sharuminar simply gave him leave to do whatever he thought would best help France, but not to expect British aid.

The third set of talks on the 29th June represented a sudden change of heart from both leaders. De Gualle decided that his campaign for Free France would be waged through political, not military methods, and for the time being he would concentrate on returning French colonies - now occupied by Vichy France - to his control. The British Prime Minister responded with a promise that he would review the situation of Vichy France following a definite victory against Italy. Furthermore, he would approve the French request that aircraft and ships be produced in Britain for use by Free French forces.

The meetings with De Gualle left Kan Sharuminar quite exhausted, and quite unwilling to go through another such meeting. With this in mind, he appointed Peck of Arabia to the post of Foreign Minister, assuring him he had free reign in maintaining diplomatic relations with other countries. To that end, his first duty was to travel to the Soviet Union, to meet with Joseph Stalin in the hopes of renewing more cordial relations.

Peck travels to Moscow

Having been gifted the Prime Ministers former transport aircraft, an Armstrong Whitworth Ensign named Excalibar i, Peck began a treacherous journey to Russia. Stopping to refuel at Narvik before heading to land at Archangel, he was constantly under threat of attack by German fighters. He had left Britain early on the 1st August, just as the German invasion of southern Norway was in full swing. Arriving in Russia the next day, he was given a reception as cold as the local climate, with little reception for his arrival and a single car to take him to Moscow. Travelling in silence for the majority of the trip, Peck could be forgiven for desiring a return to the tension-filled air journey he had just completed.

Moscow itself was not much better. Stalin had apparently declared himself indisposed, leaving Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov to meet with Peck. After a small welcoming ceremony, Molotov launched an attack against the prowess of the Allies following their poor showing in France. He condemned them for the cancellation of trade between the Allies and the Soviet Union, and for protesting the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States, Bessarabia and the recent war against Finland. He finished with the claim that it was Britains military expansion in the 1930s that had provoked Hitler into action, and that the Allies had no-one but themselves to blame for their current predicament.

It was not the opening reception that Peck had desired.

The next few days were less stressful, and as time past it became clear that Molotovs rant was either a long-desired venting of the Allied war effort, or simply a ploy to put the new British Foreign Minister on edge. Indeed, whenever Molotov returned to the subject of the French defeat, Peck of Arabia got the feeling that Stalin had been caught as off guard as the Allies had been, and had realised he was in an unenviable position, what with the bulk of German forces now available to threaten Russia. At one point Molotov asked about the possibility of an Allied landing in France, though he did so under the suggestion it would restore the prestige of the British military to what it once was.

Relations slowly became more amicable as discussions continued, and certainly Molotovs attitude improved once Peck promised that Soviet-British trade could resume in the near future. Despite the lavish interiors of the Kremlin that Peck was allowed to see in his discussions, he had the definite impression that the Soviet economy was on the verge of collapse - Molotov constantly suggesting trade deals of Soviet resources for Allied money. Ultimately, all Peck could do was promise that he would do what he could, but he was sure the Cabinet would have no problem with such a deal. He departed Russia on the 7th August, once again making the perilous journey across Scandinavia and the North Sea.

The candidates for Presidency, 1940

Prime Minister Sharuminar had not distanced himself completely from diplomatic relations, making a brief visit to the United States on the 24th August. It was just a two-day visit, what with Roosevelt in the middle of an election campaign and the war in North Africa coming to an end, both leaders had little time for each other.

Being the two commander of the free world, that had to change, and while the brief meeting in Washington was meant as an outward show of British-American relations, for the two leaders it was to get a better idea of each other. Roosevelt was clearly leaning towards giving aid to the Allies, and hinted at a future oil embargo against Japan, but he could hardly side with a Britain still Imperialist in nature - an important matter now that Britain was undisputed masters of north, east and southern Africa.

He was answered with the revelation that Britain had no intention of keeping any territories it captured during the war, except for short-term strategic operations. If Roosevelt wanted proof then he should look no further than Abyssinia, a free nation cruelly taken by the Italians, now liberated by the British Empire. Looking quite pleased with himself, Kan Sharuminar announced that the Abyssinian government had arrived home just three days previously, and would declare full freedom on the 30th August - one year to the day that war broke out with Germany.

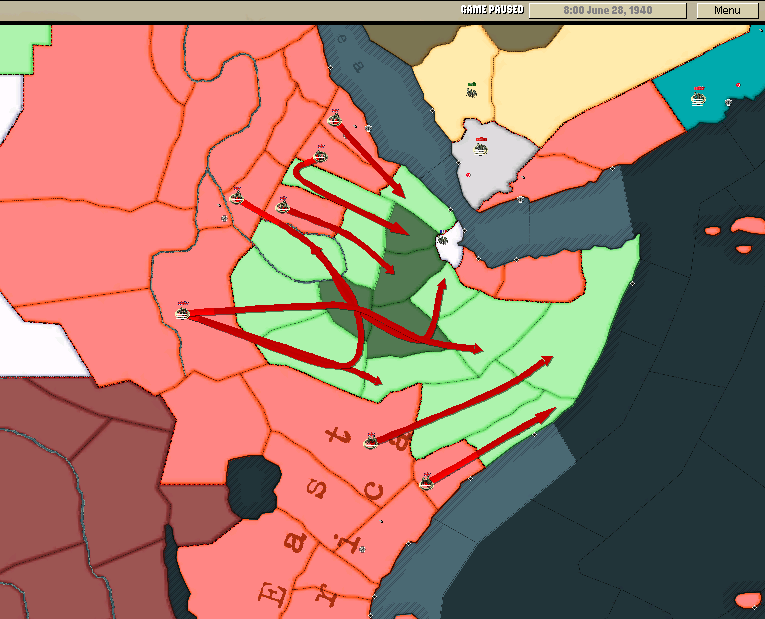

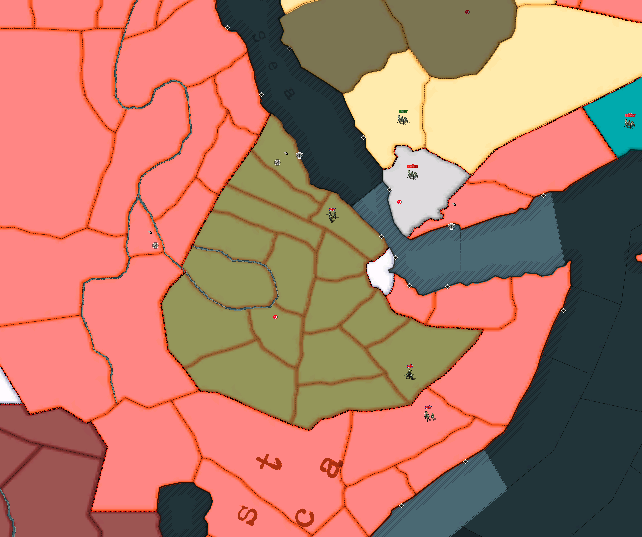

The Abyssinian Campaign

Even before the war against Italy broke out, preparations for the liberation of Abyssinia had been in place for many months now. The shocking news that Italy had left its most recent possession in Africa undefended was taken with some scepticism, and as such all nine militia divisions already in east Africa were utilised for the liberation. When the invasion commenced, it was discovered that intelligence had been completely correct, and the only resistance that the British militia fought was the terrain. It took two and a half months to retake all Abyssinian provinces, though such a bloodless campaign was welcoming after the destruction in France, Libya and Norway.

Free once again, Abyssinia had already declared its intentions to join the Allies and the greater war effort. Roosevelt could be assured that Libya would receive the same treatment, but in this case only after the war had ended. It was a vital location for the Mediterranean Campaign and any future campaign against the Italian mainland. All in all Roosevelt was pleased, though he did note that questions regarding the self-determination of Britains

existing colonies went unanswered.

Abyssinia liberated!

Prime Minister Kan Sharuminar returned to Britain on the 27th August, quite convinced that Roosevelt was his ideal choice of President for the next four years. While the American leader hadnt given any definitive statements of aid or direct participation in the war effort, the Prime Minister assured himself this was only due to necessity. Roosevelt could hardly announce such intervention list measures so soon to an election, to a populace who firmly believed in Americas isolationist policies.

For now, Britain remained alone. But it remained alone with good company