You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Consciousness: what it is, where it comes from, do machines can have it and why do we care?

- Thread starter Samson

- Start date

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

The closest simplification to that idea I like working with is:Are you aware of orchestrated objective reduction that postulates that consciousness comes from quantum effects within the subcellular component microtubules? I have never thought so much of it, I cannot see any reason to believe it happens there, but some clever people like the idea.

Consciousness is represented by intermittent, chaotic flows of protons (H+) within the cerebro-spinal fluid.

Neurons detect H+ ions through gaps and junctions in microtubules; glial cells may also play a role in detecting and processing pH differences external to neurons.

Note: I said "represented by", not "is".

I have no real interest in what consciousness "is". That's a matter for philosophy, not mathematical physics.

And the notion of "quantum consciousness" is really speculative atm, and way beyond me.

(For my purposes, pH is the abstraction I'm trying in conjunction with evolutionary strategies for "simple" function optimization. )

With microtubules, there are some equations that can lead to useful models. However, even the simplified models involve a Schrodinger-like equation, an ugly beast related to the Gross-Pitaevskii equation (or a noisy Langevin equation).

All I want and need for my model is the speed at which protons move along the inside of microtubules via the so-called "Grotthuss mechanism". Even more simply, their speed relative to the Ca++, K+ and other ions travelling along the outside of dendrites and teleo-dendrites.

Penrose tried to counter Max Tegmark's criticism that quantum effects won't be stable because the brain is "warm, wet, and noisy".

He suggested that the inside of the tubules are "shielded" in some way.

Unfortunately, there is very little information on what actually happens inside tubules.

They are extremely small as can be seen in the images: magnifications are 580,000X in A and 470,000X in B.

From: G. Zampighi. Gap junction structure. In W. C. de Mello, ed., Cell-to-Cell communication, chapter 1, pages 1–28. Plenum Press, N. Y., 1987.

(And, yes, they are packed into hexagonal structures. Go Bestagons!)

Microtubules are omnipresent in cells and cerebral fluid. They are essential in many biological processes and they have fairly short lives.

Except in neurons where they are permanent, i.e. they exist for the life of the neuron.

They are also present in larger volumes of cerebro fluid where there are no cell walls or other structures to closely confine them, which suggests to me they are possible means by which different concentrations of H+ ions can be re-distributed quickly.

That meshes perfectly with another theory: Everybody has an idea which simply does not work.

Excuse my lack of coherence. It's 40C here, a lone saxophonist has been playing mellow tunes for the last two hours at the gin joint 20 metres from my window, and bats are dropping out of the sky onto the heads of music and comedy festival goers.

And the two sentinels that @Kyriakos is interested in will both tell the truth because they are simply unable to summon up the energy to lie.

Narz

keeping it real

Daniel's necessities for consciousness are arbitrary and not even correct.My very inexpert summary is that consciousness is actually defined by agency, which requires both a biological basis, which computers do not have, and a understanding of the wider consequences of our actions, which dolphins do not have.

Humans don't have agency any more than an ant or the wind, we just think we do.

Why would consciousness require a biological basic? Just seems like ignorance and ego to say that.

Daniel Dannet is proof that thinking about something for a long time and having opinions on it doesn't make you an expert on it and in fact can make you dumber as you get more entrenched in comforting ideas.

Narz

keeping it real

Sounds fun. What's the festival called?Excuse my lack of coherence. It's 40C here, a lone saxophonist has been playing mellow tunes for the last two hours at the gin joint 20 metres from my window, and bats are dropping out of the sky onto the heads of music and comedy festival goers.

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

Adelaide Fringe: 16 Feb. to 17 Mar. 2024.Sounds fun. What's the festival called?

About Adelaide Fringe | Adelaide Fringe - 16 February - 17 March 2024

We are Adelaide Fringe, the Biggest Arts Festival in Australia! We were born 64 years ago (although we don't look a day over 25) and for 31 magical days and nights each year we completely take over the beautiful city of Adelaide, South Australia.

WOMADelaide 2024 Lineup

Browse the 2024 lineup featuring, Ziggy Marley, Baaba Maal, Jose Gonzalez and more.

YMMV. (Not every year features dead bats dropping from the sky.)

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

Asimov used the idea of the positronic brain in his robot stories."Computation without computers?"

From Asimov's nice story, "The Feeling of Power".

Microtubules as proton wires connecting different regions of neurons or cerebro-spinal fluid isn't far removed, just a little less hand waving.

Last edited:

Consciousness certainly happens at the molecular and atomic levels and likely at the quantum levels.

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

Excellent hypothesis! All you need now is evidence, a definition of consciousness and a tuxedo for your Nobel Prize ceremony.Consciousness certainly happens at the molecular and atomic levels and likely at the quantum levels.

If one defines consciousness as "awareness" sufficient to cause action, then the physical properties of matter at the molecular and atomic levels are a form of rudimentary consciousness that expands with complexity to include all matter living and dead. There is already lots of evidence of how proximity of atoms and molecules will cause things to happen. Currently, most folks label such behavior as an innate property of of chemistry or physics and in voluntary, so it can't be consciousness at work. Those people rarely actually define consciousness clearly but they always seem to know what it is not.Excellent hypothesis! All you need now is evidence, a definition of consciousness and a tuxedo for your Nobel Prize ceremony.

By defining it the way I do, the definition problem goes away along with trying to find the edges or lines we like to drawn around things to include or exclude what we like and don't like.

By defining it the way I do, the definition problem goes away along with trying to find the edges or lines we like to drawn around things to include or exclude what we like and don't like.Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

What is "awareness"?If one defines consciousness as "awareness" sufficient to cause action, then the physical properties of matter at the molecular and atomic levels are a form of rudimentary consciousness that expands with complexity to include all matter living and dead. There is already lots of evidence of how proximity of atoms and molecules will cause things to happen. Currently, most folks label such behavior as an innate property of of chemistry or physics and in voluntary, so it can't be consciousness at work. Those people rarely actually define consciousness clearly but they always seem to know what it is not.By defining it the way I do, the definition problem goes away along with trying to find the edges or lines we like to drawn around things to include or exclude what we like and don't like.

"Walking rocks" move in response to their environment and give the impression they are living aware beings. I can't find a reason atm why ancient humans (and other "primitive animists") would believe that they are not.

The closest I have seen that satisfies me is a hypothesis (I stole and cobbled together from others) about how consciousness might first have arisen.

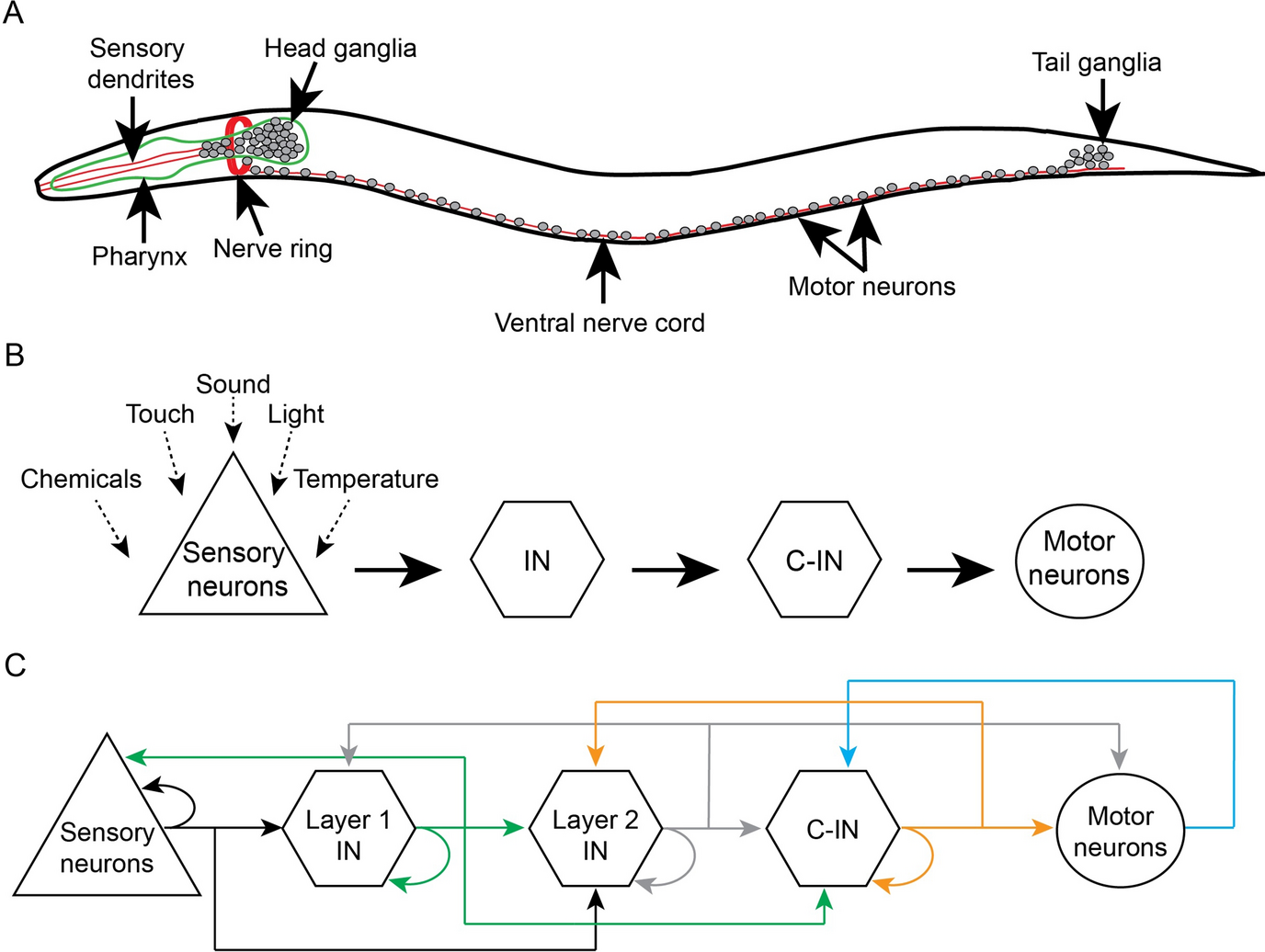

In one of biology's favourite creatures, C. elegans, there is one neuron (out of the precisely 302 it possesses) whose sole function is to recognise "this is me".

Primitive eyes, or "aesthetes" can sense variations in the levels of light, chemicals and pressure in their immediate surroundings.

Early living creatures lived in the sea, where light is very limited: aesthetes cannot detect changes very far away.

As creatures evolved and eventually moved onto land, those primitive aesthetes (explicitly present and expressed, or buried in their genetic lineage) could have become an extraordinary advantage because they could sense changes in light levels much further way.

That advantage in turn, and over long time periods, could have led to "planning". In water, where vision and other sensory mechanisms are very limited, planning is not as important as "sense and flee immediately" or "sense and eat it immediately"

Of course, just like your idea it is extremely speculative, and it has some grounding in physics and chemistry. Philosophers and meta-physicians can form their own working subgroups and report back later.

Ever onwards, comrades!

The first results of experiments funded by the Templeton Society(?) came out last year. There were about 20 "contestants". And with typical American brilliance at entertainment, results were posted on a huge board in front of an audience, many sporting shirts and sweaters emblazoned with the name of their "team". (Don't ever lose that penchant for razzle dazzle, you American dahlings!)

The funniest part of the competition was that a psychologist came up with a brilliant (IMO) plan:

Get the competitors of opposing theories to agree on an experiment that will determine which one is correct.

So, David Chalmers and his team pitted themselves against the Crick Institute(?) and off they went.

An interviewer asked the psychologist what he thought might happen with the results.

"I doubt that anybody will change their ingrained opinions because of the experiments", he said.

What you'll see is that their collective IQ's will increase 15 points and they will find flaws in the experiments which will explain why they lost".

And, yea verily, that's how it turned out, for all humans are conscious bozos on this bus, whether we know it or not.

Results from other experiments are due to be completed and released later this year.

The Enb.

You are the only one talking about walking rocks. Awareness as I see it is the capability of a thing to respond in some fashion to the proximity of some other thing. rocks are made up of different types of minerals? or other rock like materials that are made up of various atoms and molecules. Those atoms and molecules do respond in chemical and physical ways to heat, cold, water, other forces, etc. The primitive awareness built into the most basic elements of matter create change. In more sophisticated objects, a more capable level of awareness can be found in cellular life. It is really just about how one chooses to define things. Our human centered pov tends to dismiss many things because we view ourselves as some higher order and more important aspect of life. Our current standard view of consciousness is all about self recognition (mirror test) and problem solving. As more and more critters pass these tests we will be forced to either allow that non humans have consciousness similar to us or we will find a new way to define it so they don't. What happens when it is declared that factory farmed animals conscious beings?

How does it do that? I'm sure that there is some chemical or quantum process that is part of activity. "recognizes self" is just an extension of whatever that process is. It is a slightly more complicated capability over cells without it. Consciousness is a long continuum of evolving complexity in all matter.The closest I have seen that satisfies me is a hypothesis (I stole and cobbled together from others) about how consciousness might first have arisen.

In one of biology's favourite creatures, C. elegans, there is one neuron (out of the precisely 302 it possesses) whose sole function is to recognise "this is me".

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

I was merely pointing out that some things have the appearance of being alive and being able to respond to their environment and to change it. "Walking rocks" is just one example of that.You are the only one talking about walking rocks. Awareness as I see it is the capability of a thing to respond in some fashion to the proximity of some other thing. rocks are made up of different types of minerals? or other rock like materials that are made up of various atoms and molecules. Those atoms and molecules do respond in chemical and physical ways to heat, cold, water, other forces, etc. The primitive awareness built into the most basic elements of matter create change. In more sophisticated objects, a more capable level of awareness can be found in cellular life. It is really just about how one chooses to define things. Our human centered pov tends to dismiss many things because we view ourselves as some higher order and more important aspect of life. Our current standard view of consciousness is all about self recognition (mirror test) and problem solving. As more and more critters pass these tests we will be forced to either allow that non humans have consciousness similar to us or we will find a new way to define it so they don't. What happens when it is declared that factory farmed animals conscious beings?

How does it do that? I'm sure that there is some chemical or quantum process that is part of activity. "recognizes self" is just an extension of whatever that process is. It is a slightly more complicated capability over cells without it. Consciousness is a long continuum of evolving complexity in all matter.

Sailing stones - Wikipedia

I agree that humans anthropomorphize many processes far too readily, and also that we dismiss many processes because of, what you say is the human pov.

I don't know how that particular C. elegans neuron does what it does. Nobody knows, and probably won't for a long time.

Again, I have no disagreement with you that it is a complex process.

I disagree however that it is a "slightly more complicated capability over cells without it" - it's vastly more complicated. At least combinations of Avogadro's number more complicated. A number if written down in full would not fit into the observable universe.

Neurons are fantastically complicated, and it has taken evolution hundreds of millions of years, perhaps billions to get to that level. How the 302 neurons of c. elegans interact and lead to the behaviour of the critter is something that will take humans a very long time to understand.

Recent research such as the "Atlas of Human Cells" has found well over 2,000 new types of cells, and IIRC nearly 3,000 new types of neurons. Glial cells like astrocytes, previously thought to be just a means of mopping up by-products of biochemical reactions, have been shown to be electro-chemically active. How they affect brain functions is still a mystery.

The current "Connectome Project" won't provide the answers for us; at best it will just give us more terrific data that could lead to many medical advances, but it does next to nothing to help us understand processes within each individual cell, let alone neurons.

Furthermore, it maps connections in an already fully developed brain. As embryos grow, parts of the brain that were close together end up a long way apart. Some parts of the developing brain are re-purposed because they are no longer required for their initial functions.

Just a guess: Consciousness is not a static state - it probably changes significantly through various developmental stages.

At least we have moved away from the old idea that there are specific areas of the brain dedicated to a unique function, e.g. Broca's region is where "language" and "speech" resides.

By the time you finish reading a sentence like, "The blues - they're a dreadful team, but they have a great club song." it has triggered activity in different parts of the brain, combined them in different ways in different individuals, evoked different memories and different unique feelings.

"Consciousness is a long continuum of evolving complexity in all matter."

But that still remains to be demonstrated. My main disagreement is with that assertion is the use of the term "all matter".

"As more and more critters pass these tests we will be forced to either allow that non humans have

consciousness similar to us or we will find a new way to define it so they don't."

That distinction already exists to some extent. Among other aspects, living organisms, from the unicellular to higher primates,

have never been shown to possess the knowledge that they will eventually die. The old "sapience and sentience" aspects of human existence have never been shown to exist in other lifeforms.

But I agree that we will eventually develop finer distinctions, clearer ways to include and exclude some lifeforms.

Until a new theory, or a newly discovered lifeform, or something that crawls out of Craig Venter's lab sticks it head above the parapet and ruins the previous carefully constructed edifice.

I'm also not arguing that nonhuman lifeforms don't have the appearance of some similarities to human consciousness, but that's a long way from demonstrating that they are, in actuality, similar.

Scientific validity requires an accompanying measurement, or it's not really science.

And if someone claimed that their measurements demonstrate that animals possess consciousness that is (for sake of argument) 50% similar to human consciousness, what would that even mean? I reckon bugger all.

The competition and research activity I mentioned in my earlier post is an attempt to find some definite, measurable quantities or processes that are linked to consciousness.

One experiment is based on what is known as "binocular rivalry".

You probably know the famous picture which is the illusion of either two faces or a vase. Humans can see one image or the other, but not both at the same time *.

At the instant when we switch from seeing one image to the other, neuroscientists claim that consciousness should be apparent and some aspects should be measurable.

The experiments at several different establishment will be finalised later this year.

* I would contend that humans are much smarter than that. They know they are part of an experiment

and therefore they also have a kind of bird's eye, meta view of the whole situation, which IMO will

muddy the measurements that are made. Just a guess of course.

I don't know either, but I do surmise that chemical and quantum properties are involved.I don't know how that particular C. elegans neuron does what it does. Nobody knows, and probably won't for a long time.

So the "this is me" moment comes at the moment said neuron appears. Prior to that moment, was C.elegans not C. elegans? Or nearly there? How big a step was it? Did the change happen when 301 neurons added one more? did it happen when C. elegans moved to neuron 295 from 294? However it happened a continuum of evolving conscious capability seems likely to be in play. As more elaborate and complex chemical and quantum interactions happen and manifest in new physical forms, new things happen. Viruses are an interesting example of what we don't know. How were they (if they were) involved in the transition to cellular life? Are they living? And at the other end, how did non living cells evolve from non cellular stuff? With each transition we see improvements in capabilities and greater complexity. Tiny steps over many years that seem to involve many very small changes. With each we get a bit more "awareness" and closer to the C. elegans "this is me moment.C. elegans, there is one neuron (out of the precisely 302 it possesses) whose sole function is to recognise "this is me".

Yes that is a pretty all encompassing statement. I have no proof of course, but.... The chemical, molecular and quantum properties of non living things are part of the processes that make living things living. The physical nature of the matter involved has changed (from often hard to softer) but iron atoms in a rock are no different than iron atoms in the blood. They have a different function perhaps and interact with different things in racks versus when in blood. If consciousness resides in living things but never in non living things then at some point "magic happens" and it appears. My point is that I think conscious is a natural thing that is ever present in nature and as complexity grows it begins to manifest itself more obviously."Consciousness is a long continuum of evolving complexity in all matter."

But that still remains to be demonstrated. My main disagreement is with that assertion is the use of the term "all matter".

This is just another way of defining consciousness such that we can exclude some living things and not others. BTW there is evidence that some cats can sense the death of people."As more and more critters pass these tests we will be forced to either allow that non humans have

consciousness similar to us or we will find a new way to define it so they don't."

That distinction already exists to some extent. Among other aspects, living organisms, from the unicellular to higher primates,

have never been shown to possess the knowledge that they will eventually die. The old "sapience and sentience" aspects of human existence have never been shown to exist in other lifeforms.

Do Cats Know When They Are Dying?

How do cats experience their final days? Do they know they are about to die, and how can you comfort them?

www.petmd.com

So I ask you. Is consciousness one thing that we can fix limits too? Is that important and if so, why? Do dogs understand love? Does the mother-baby bond that is found across the animal kingdom fit the I and Thou relationship of knowing that "this is me and that is you" we humans deem so important?

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

Sure, but that's not much different to saying that there is a Michelangelo's David inside every sufficiently large lump of marble.If consciousness resides in living things but never in non living things then at some point "magic happens" and it appears. My point is that I think conscious is a natural thing that is ever present in nature and as complexity grows it begins to manifest itself more obviously.

This is just another way of defining consciousness such that we can exclude some living things and not others. BTW there is evidence that some cats can sense the death of people.

Yes, I gave it as an example of what we already use to include and exclude.

As to cats...you must demonstrate that they are aware of their own finite lifespan. Not that they can do a Mystic Meg on a human.

So the "this is me" moment comes at the moment said neuron appears. Prior to that moment, was C.elegans not C. elegans? Or nearly there? How big a step was it? Did the change happen when 301 neurons added one more? did it happen when C. elegans moved to neuron 295 from 294?

Maybe, maybe not. I don't know. Maybe the change happened at step 1.

I agree with you that it is related to chemical processes, but it is not always of use to add "quantum". You might as well throw in quarks as well and claim "it's the quarks inside nuclei that cause consciousness to arise and exist".

Quantum physics is useful to describe individual particles. Chemistry uses different terminology because it deals with large numbers of atoms and molecules.

One "thing"? I doubt it.So I ask you. Is consciousness one thing that we can fix limits too? Is that important and if so, why? Do dogs understand love? Does the mother-baby bond that is found across the animal kingdom fit the I and Thou relationship of knowing that "this is me and that is you" we humans deem so important?

If a plant is conscious in some way, so what? What is 1% similar to human consciousness mean? To me it suggests somebody cherry picked a similarity and ignored all the rest.

The "consciousness" of an individual leaf is not necessarily the same as the "consciousness" of the whole plant.

The "consciousness" of an individual ant is not necessarily the same as the "consciousness" of the hive, if that is even a "thing".

As to dogs: "Understand" and "love" are human constructs, so not really relevant to the argument.

The mother-baby bond...?

I don't know. Possibly. But it's not necessarily similar to what human's experience.

E.g. animals might also possess "this is me, you are my baby that is screaming as I chew your liver out."

They are all aspects from the human pov. I suggest it's another cherry picking exercise and a bit of wishful thinking (no pun intended). Just the same as people who claim Large Language Models are becoming close to humans in some way.

And so to the gist of our disagreement

For sake of argument, I'm happy to agree with you everything you've written, except on one major point.

I do not accept that consciousness is inevitable as complexity increases.

I think that you are making a fundamental error: confusing potentiality with inevitability.

Again, for sake of example: Suppose that we have an infinite universe and and an infinite amount of time.

That does not mean that one particular "thing" must eventually and necessarily occur.

If you want to reject the notion of an infinite universe and infinite time, then let's take a "finite universe and finite amount of time".

Then, I'd argue there is even less reason to accept the inevitability that something like consciousness will necessarily arise.

Manfred Belheim

Moaner Lisa

- Joined

- Sep 11, 2009

- Messages

- 8,404

Can you give a reference to anything about this "this is me" neuron? You're saying you don't know how it does that, but I'd be interested to know how/why anyone thinks it does that at all.

Quick response for now:And so to the gist of our disagreement

For sake of argument, I'm happy to agree with you everything you've written, except on one major point.

I do not accept that consciousness is inevitable as complexity increases.

I think that you are making a fundamental error: confusing potentiality with inevitability.

Again, for sake of example: Suppose that we have an infinite universe and and an infinite amount of time.

That does not mean that one particular "thing" must eventually and necessarily occur.

If you want to reject the notion of an infinite universe and infinite time, then let's take a "finite universe and finite amount of time".

Then, I'd argue there is even less reason to accept the inevitability that something like consciousness will necessarily arise.

"inevitable"? maybe not but looking aback at what we know about life on earth are there examples of more complex life not having an "improvement" in consciousness? Can you offer your definition of consciousness or its threshold?

I would throw out both "potentiality and inevitability" and just go with "self awareness seems to increase as mental capability grows more complex."

An infinite or finite universe makes no difference to me, but for the record, I think our current view of the expanding universe is on the right track. I am not a fan of the "many worlds" view multiple universes.

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

Thanks a lot for putting me on the spot by asking for a cite!Can you give a reference to anything about this "this is me" neuron? You're saying you don't know how it does that, but I'd be interested to know how/why anyone thinks it does that at all.

I can't remember if it was a video lecture, or from a Machine Learning Street talk podcast, or in a journal I read.

The closest I have in my collection is to this paper which mentions propriocentesis in C.elegans.

That "sense" is effectively the "this is me" and externally "not me" for this critter.

Open access paper you can download:

Oressia Zalucki, Deborah J. Brown, Brian Key,

What if worms were sentient? Insights into subjective experience from the Caenorhabditis elegans connectome

Biology & Philosophy (2023) 38:34

What if worms were sentient? Insights into subjective experience from the Caenorhabditis elegans connectome - Biology & Philosophy

Deciphering the neural basis of subjective experience remains one of the great challenges in the natural sciences. The structural complexity and the limitations around invasive experimental manipulations of the human brain have impeded progress towards this goal. While animals cannot directly...

When I find the exact cite I'll post it, but I read more than 10-20 papers a day, and my wife and I listen to about 8-10 hours of lectures and various fiction works (audio books, podcasts etc) per day so it could take me a while to remember where I got it.

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

No quick example, but the closest I can offer now is that consciousness could just be a spandrel of evolution, a "side-effect" of natural selection for other traits. Therefore it could either reduce or increase as animals evolve. There is no inevitability of consciousness improving (or deteriorating).maybe not but looking aback at what we know about life on earth are there examples of more complex life not having an "improvement" in consciousness?

Can you offer your definition of consciousness or its threshold?

No! Many very clever people have tried and so far failed.

I had a great laugh when brain boffins decided that this was an unsatisfactory state of affairs, so they organised a very large conference in Oxford(?) around 2000.

I read many of the papers in the Proceedings, and there was no consensus.

Many definitions were offered, but just as in the latest "competition", I think everybody's IQs were raised by 15 points and they found fault with everyone else's definitions. So, it's still nil all in that game!

Here's some ammo in favour of some of your arguments as a consolation prize.

From: What Is the Nature of Consciousness? (An interview with Anil Seth).

But I mean, we humans, we have this tendency to anthropomorphize, to project conscious minds into things that are similar to us in a way that’s overly shaped by their similarity to us or how they interact with us. And this can lead us to assign consciousness of a particular kind to things that might not have it and deny it to other things that might. The key thing to remember when considering this question is that consciousness — this brings us back to the beginning — is not the same thing as intelligence or having reason or having language or anything like that. It’s any kind of experience whatsoever.

So if we judge other animals by their possession of these kinds of human-like characteristics, then we’re going to go wrong. All mammals share the same basic neuronal hardware that seems critical for consciousness in humans. That’s my claim, anyway; not everyone is going to agree with that. But I think it’s a done deal to assume that all mammals, and this includes mice, rats, dolphins, as well as monkeys, orangutangs, and so on, are conscious. But in different ways — you know, we humans, we just inhabit one small region of a vast space of possible minds. Beyond mammals, it gets really hard. And we still can’t help being driven by intuitions. I spent a week with octopuses many years ago in Italy. And this made such an impression on me because these creatures, they don’t seem similar to us at all. But the sense that there’s a conscious presence there is so palpable. They have a curiosity about their world. And they have a lot of neurons too.

But there’s a big challenge. I think it’s very likely that very many animals have consciousness because consciousness is a very functional thing. You know, it brings a lot of information together for an organism in a way that’s sort of unified and also informative with respect to what actions should be made. We experience the body in motion and the state of the world all kind of at once. So it’s solving a problem for organisms about how to take a lot of things into account in a relevant way for continued survival. So I think it’s likely, but it’s incredibly hard to come up with 100% confidence about this stuff, especially when we get beyond mammals to insects, to fish, to bacteria. Where do you draw the line? It’s very hard — or even to know whether there is a line to draw, or whether consciousness just kind of peters out into nothingness in a very, very graduated fashion.

So the strategy that I think is best is we just need to generalize out very slowly. And the more we learn about the basis of human consciousness, the more we can understand about how conscious experiences might unfold in other animals. And the extent to which that’s true across all animals — the further we go, the harder it is. But we should try. And when in doubt, there’s this thing called the precautionary principle, which is to basically be quite conservative about this and say, OK, if there’s a chance that X is conscious, let’s assume that’s true, so that we don’t cause suffering unnecessarily.

Bingo, we are in agreement finally. I'm probably a lot more scathing in my opposition to the idea than "not a fan".An infinite or finite universe makes no difference to me, but for the record, I think our current view of the expanding universe is on the right track. I am not a fan of the "many worlds" view multiple universes.

Manfred Belheim

Moaner Lisa

- Joined

- Sep 11, 2009

- Messages

- 8,404

I wasn't attempting to put you on the spot, I was just interested and couldn't find anything about it during my admittedly brief google.Thanks a lot for putting me on the spot by asking for a cite!

I can't remember if it was a video lecture, or from a Machine Learning Street talk podcast, or in a journal I read.

The closest I have in my collection is to this paper which mentions propriocentesis in C.elegans.

That "sense" is effectively the "this is me" and externally "not me" for this critter.

Open access paper you can download:

Oressia Zalucki, Deborah J. Brown, Brian Key,

What if worms were sentient? Insights into subjective experience from the Caenorhabditis elegans connectome

Biology & Philosophy (2023) 38:34

What if worms were sentient? Insights into subjective experience from the Caenorhabditis elegans connectome - Biology & Philosophy

Deciphering the neural basis of subjective experience remains one of the great challenges in the natural sciences. The structural complexity and the limitations around invasive experimental manipulations of the human brain have impeded progress towards this goal. While animals cannot directly...link.springer.com

When I find the exact cite I'll post it, but I read more than 10-20 papers a day, and my wife and I listen to about 8-10 hours of lectures and various fiction works (audio books, podcasts etc) per day so it could take me a while to remember where I got it.

I haven't read the full paper you linked, but the abstract seems to be saying the exact opposite of what you're saying (unless I'm misunderstanding) - that they find against subjective experience in the worm and question the validity of using motivational trade-offs as an indicator of subjective experience in general.

I'm afraid I don't know what "propriocentesis" means, but the word doesn't appear to feature in that paper and google doesn't seem to give any hits for it either. I guess it's a misspelling of something?

Comrade Ceasefire

Simmer slowly

You putting me on the spot about the cite was just a joke.I wasn't attempting to put you on the spot, I was just interested and couldn't find anything about it during my admittedly brief google.

I haven't read the full paper you linked, but the abstract seems to be saying the exact opposite of what you're saying (unless I'm misunderstanding) - that they find against subjective experience in the worm and question the validity of using motivational trade-offs as an indicator of subjective experience in general.

I'm afraid I don't know what "propriocentesis" means, but the word doesn't appear to feature in that paper and google doesn't seem to give any hits for it either. I guess it's a misspelling of something?

Propriocentesis is a medical term, probably one I translated in my mind from Lithuanian (English is not my first language), and probably archaic now. I'll get back to that after this short interlude.

The paper uses "proprioceptive" and "proprioception".

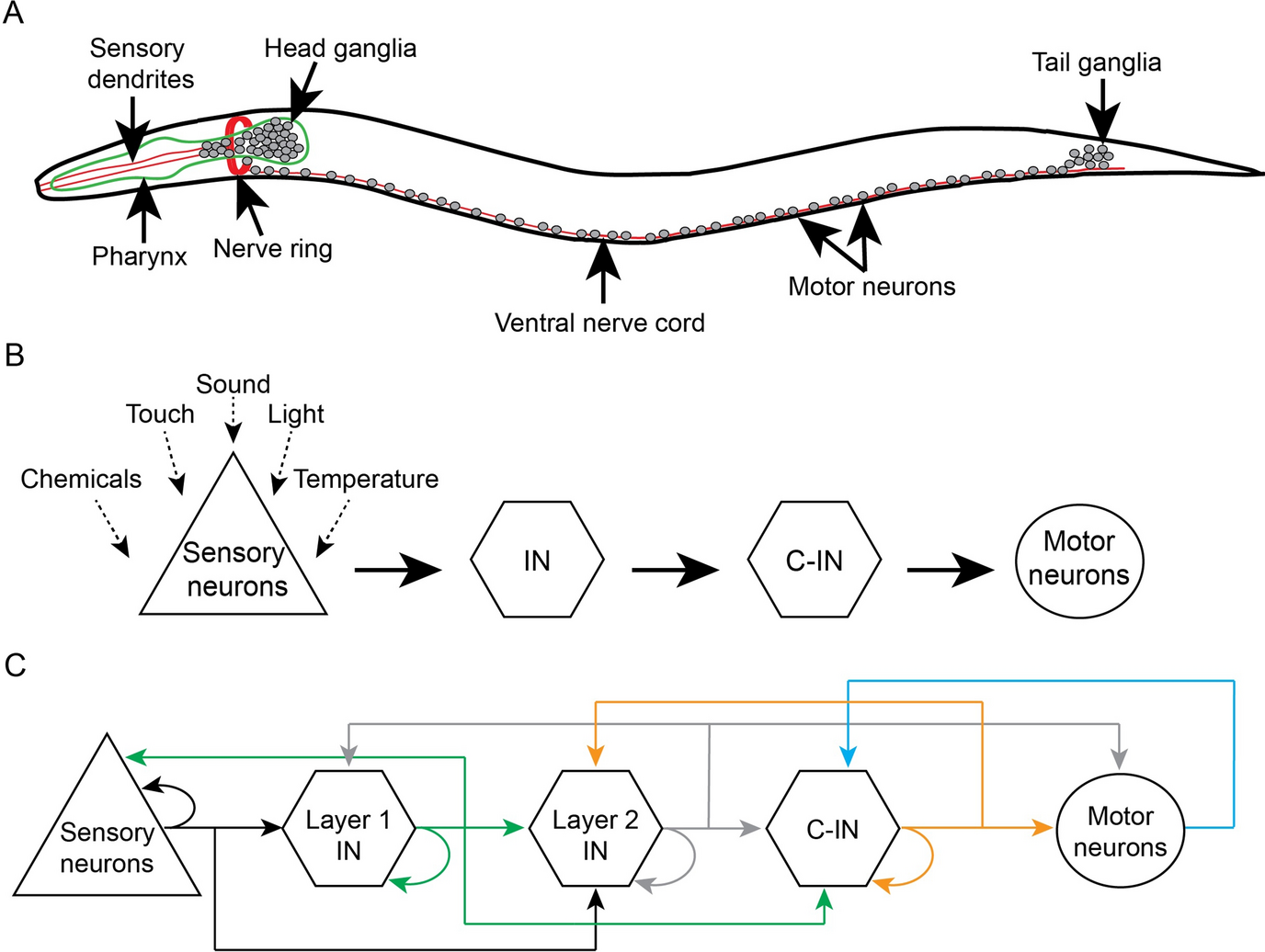

It is a kind of extra sense, apart from the usual 5: sight, sound, touch, smell and taste. In essence, it allows us to know where our body parts are without having to look for them. (There are others, e.g. vestibular which is related to balance.)

From the paper I linked to:

However, C. elegans do learn to perform targeted navigation within T-mazes in search of food rewards by using a combination of proprioceptive and mechanical sensory stimuli and they can execute that behaviour after food cues are removed.

From wiki:

The discovery of proprioception in plants has generated an interest in the popular science and generalist media. This is because this discovery questions a long-lasting a priori that we have on plants. In some cases this has led to a shift between proprioception and self-awareness or self-consciousness. There is no scientific ground for such a semantic shift.

Proprioception - Wikipedia

Back to the old country and old tymes.

Propriocentesis, the way we used to use it, was more to do with unconsciously knowing where your "extended body" is. We used it to describe how it is not just you but, for example, if you carried a baby around on your hip, you knew where its limbs were and importantly its head was, so you wouldn't hit it against a frame when you walked through a doorway.

You could even extend it to inanimate objects, like a pen you are holding, or even a rapier after a long time learning to fence.

My wife just mentioned that it could also apply to the car you drive. After a long time owning the same car, there is a kind of unconscious feeling for what gaps you can squeeze it through, or if you will be able to park in a particular space or not.

Another paper that might be of interest while I am still looking for the one about origins of consciousness.

If I keep you busy you won't notice how long I'm taking.

Diego Becerra, Andrea Calixto, and Patricio Orio,

The Conscious Nematode: Exploring Hallmarks of Minimal Phenomenal Consciousness in Caenorhabditis Elegans

Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2023 Jul-Dec; 16(2): 87–104.

Published online 2023 Oct 10. doi: 10.21500/20112084.6487

Attachments

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 43

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 39

- Views

- 2K