[size=18pt]

National Profile: French Union[/size]

France is an idea. France is progress. France is stubborn. As

Unity left the Sol System, France was still synonymous with political erraticism, fashion,

haute cuisine, automation, civilian use of nuclear energy, and, less salubriously, colonial repression.

France spent the twenty-first century attempting to unwind the long diminution of its political, cultural, and economic relevance during the nineteenth and twentieth. This meant bloody attempts to retain the crown jewels of its old colonial empire and refusal on principal to integrate with political and economic initiatives not of its own making.

Results varied. French ambitions exceeded French resources. Until the mid-1960s, France was essentially a pensioner of the United States and a junior partner to Great Britain in ham-fisted attempts to reassert European prerogatives in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Despite some success, this humiliation was too much to bear, and, starting as early as 1958 under the leadership of war hero Charles de Gaulle, France began to chart the independent and often-hypocritical course in world affairs that his many less-talented successors would follow for another hundred and fifty years.

Paratroopers of the 1er Régiment de Parachutistes d'Infanterie de Marine

watch their comrades drop in Laos, 1971.

Politically, France succeeded in retaining Algeria, much of Lebanon (divided with Israel), and most of Indochina. A combination of American bombers and gifts of tactical nuclear weapons salvaged major blunders at Điện Biên Phủ, but the wayward colonies remained bleeding ulcers, atrociously expensive to pacify and severely divisive at home. Student riots and labor strikes became a semi-permanent feature of life in continental France, so common they reshaped the work week and dictated train schedules. Workers received automatic time off because employers could not prevent their attendance at demonstrations. White settler populations grew explosively from the mid-twenty-first century as rising sea levels in Europe made emigration to war-torn colonies more attractive, and together with ex-servicemen and local garrisons, formed a power bloc that French presidents crossed only at their mortal peril.

This great inversion of power tempted politicians to use all three subjugated nations in ways they would not have used their own. Southern Algeria and French Polynesia became testing grounds for the French nuclear weapons program. In 2030, the DGSE sabotaged Friendship Station Nam Đinh in North Vietnam, which melted down unexpectedly at the cost of eight hundred thousand lives. Ecological advocate Deirdre Skye explained this cruel dynamic to tens of millions of readers for the first time in 2059:

Deirdre Skye said:

The more they were victimized by the decades of atomic fallout caused by tests and by war, by the countless industrial accidents encouraged through weak regulation, by environmental travesties inflicted through the utter carelessness of their colonial masters, the greater was their dependency on the administrative and logistical powers those same masters refused to let them build for themselves. This was the essence of colonialism. We would beat them until they cried out for us. – The Eden Thesis

After a period of post-war adjustment in the mid-twentieth century, the gross domestic product of France consistently ranked fifth or sixth globally. Led by strong energy, agricultural, recycling, and heavy manufacturing sectors, the French economy was diverse and its workforce highly skilled. Behind the two superpowers, France was third in the sale of defense products. Behind the United States and Japan, French firms vied with those of India for third place in the sale of consumer electronics equipment. French automakers Renault, Peugot, Panhard, and Citroën had a stranglehold on the African and South American markets.

Influenced by both national chauvinism and socialist deputies, French economic policies were blatantly protectionist. Foreigners paid dearly for access to French markets, and mercantilist policies turned Algeria, Indochina, Lebanon, and later, Quebec, into captive markets for goods and services made in France. In the late 1970s, France developed its own telephonic, videotex intranet service, the Minitel, never fully embracing the World Wide Web.

The Minitel preceded the Web and, until 2005, offered considerably more functionality to its users for lower cost, including directory services, transportation scheduling, mail-order shopping, library services, games, and chat. To encourage wider adoption of the Minitel, the French government distributed terminals at its own expense in campaigns that reached every corner of the Union. Similar gifts were made to French allies. The scheme was remarkably profitable after factoring in savings from reductions in print services, physical mail delivery, and the use of live operators. The government was deliberate in courting potential opponents of the Minitel, especially newspapers, which received preferential treatment on the service.

Eventually, the Minitel’s capabilities were surpassed by the World Wide Web both in terms of data speeds (served by dedicated lines rather than coterminously with voice traffic) and application variety. Nevertheless, the French government resisted encroachment of “foreign” services and successfully leveraged the monopoly status of the Minitel to charge “extortionate” fees to foreign entities seeking an entree into France’s

territoire électronique via the Web, which they required to be done via the Minitel. One legacy of the Minitel is that France was essentially behind a firewall. Thus, the country suffered considerably less than other developed countries during the decade of Global Information Purges beginning in 2017.

Culturally, France was safe in the hands of Élodie, Minister of Culture for three presidents, who organized for France on the Minitel an exhaustive database of language, genealogy, art, literature, music, cuisine, and national mythology that provided the pattern for the subsequent U.N. effort to index the cultural heritage of the Earth. Élodie called her achievement

La Note.

France naturally resisted the creation of the European Common Market, both from fear of competition and to discourage the success of another forum in which Britain or West Germany might press their respective national interests. To get a run in on its neighbors, France was a leader in detente, the systematic reduction of tensions with the Soviet Union, and became the major pipeline for passing western technology through the Iron Curtain. In return, the Soviets cancelled, withheld, or reduced their traditional support for insurgencies and client regimes active in French colonies.

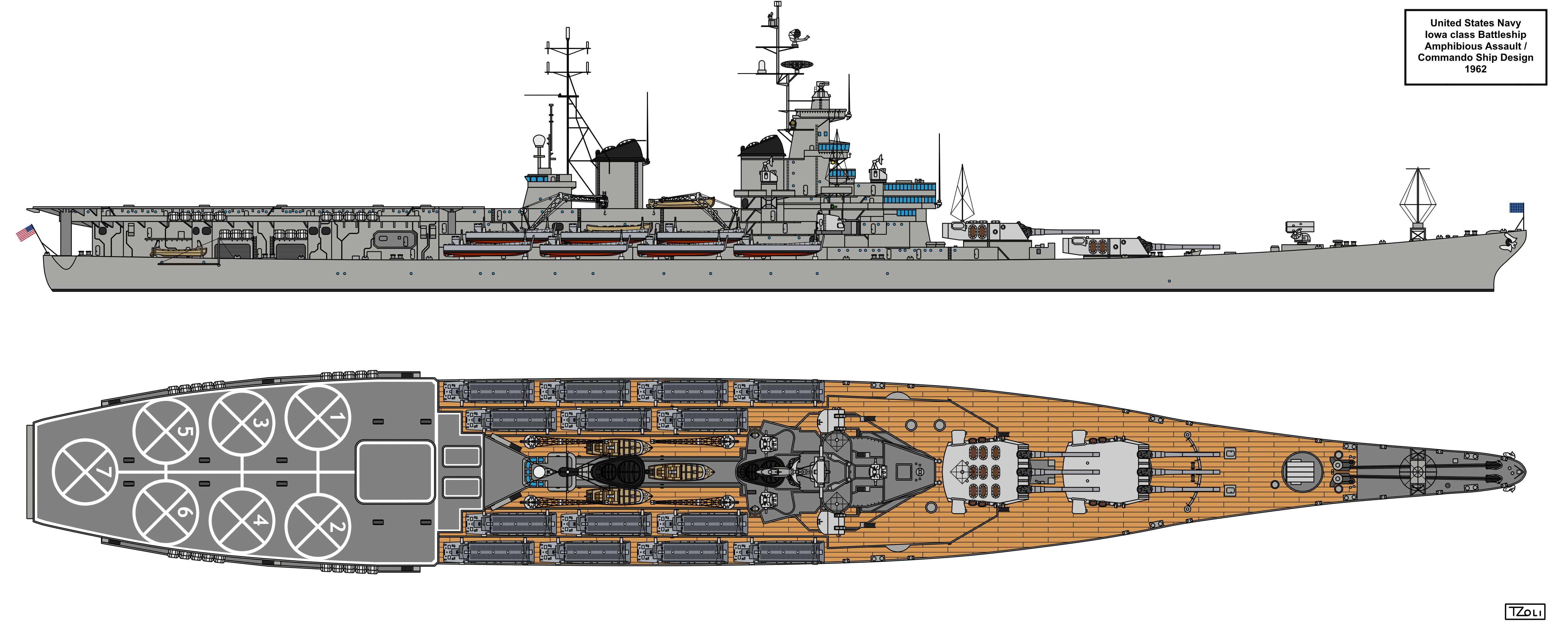

In international politics, France quit NATO. Paris refused to contemplate nuclear test bans. France also put itself forth as the patron-of-last-resort for reactionary regimes from Pretoria to Taipei and intervened aggressively in Saharan Africa under the pretext of responsibility for its former colonies. During the Burst Wars of the 2040s, Foreign Legionnaires parachuted down to preserve French-aligned governments in Mali and the Central African Republic in the face of pressure from Morgan SafeHaven. A proposal to reconstitute French Equatorial Africa (ostensibly as a bulwark against corporatism) went nowhere, however.

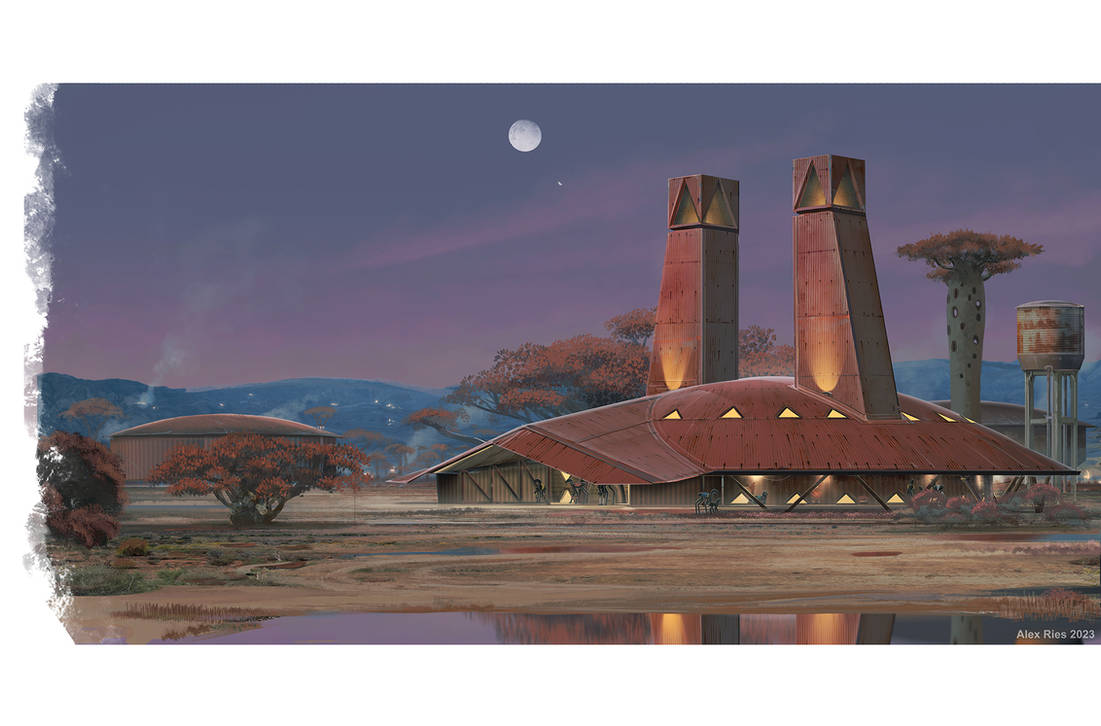

The Morgan "starscraper" obscures the moon on an otherwise clear night in central N'Djamena.

To complicate attempts at restoration of the status quo

, arms dealer Nwabudike Morgan invited Millennarian separatists to settle the Burst Zone. Promises of sweet water were mostly untrue, but his contractors had enough helicopters to give most rebels and ex-government loyalists trouble.

French intervention force deploying to fighting positions in eastern Mali ahead of an expected raid by Morgan-backed militia.

Without success, France attempted repeatedly to assume leadership of the Non-Alignment Movement, which it hoped to bulk up into a counterweight against the United Nations. This courtship was ill-fated: as an inveterate imperial power, France lacked the credibility to speak for nations that themselves were only recently liberated and wanted no part of the kind of neo-colonialism in which France unreflectively trafficked.

French domestic politics was famous for its oscillation between Socialists and Conservatives (Republicans). Socialists predictably opposed automation and favored detente with the Soviets while conservatives took opposing views. The French remained notoriously sensitive about their country’s relevance in global affairs, and proud of the manner in which they have navigated between the Scylla and Charybdis of Cold War alliances while at the same time adapting to the inundation of more than ten percent of European France’s total landmass. (Rising sea levels also claimed large swaths of populous northern Algeria and southern Indochina.) Frenchmen also credit themselves for the continued survival of pariah regimes in South Africa, Israel, Rhodesia, Biafra, and Taiwan.

Traditional Survivalism didn’t get much traction in France even among the

colons, who frequently shared the Holnist’s taste for

machismo, violence, and the politics racial grievance but preferred to suborn rather than fight the government and its all-important ministries—the best guarantees, they knew, of their precarious livelihoods. Nevertheless, revanchism gripped the French, manifesting in land-grabs on behalf of “oppressed” French-speaking minorities in Wallonia, Switzerland, and Riviera Italy during the chaos of the Floods.

Unsurprisingly, France played a major role in the Second Crisis of Québec Secession, running diplomatic and media interference for the separatists and their excesses. French companies and French intelligence helped get weapons to FLQ fighters. After Quebec gained its negotiated independence, France organized the referendum that resulted in its accession to the shambolic Union as an “independent” member. Quebec Francophones were happy to participate in this arrangement, and France soon nationalized Canadian and international firms resident in the ex-province, which became a cockpit of railroad and aerospace manufacturing. A majority of those who left France as refugees from flooding resettled in Quebec.

The French military was well-respected. The French soldier was tough, innovative, and above all, daring. The French were acknowledged experts in counter-insurgency warfare. France made its military equipment available on liberal terms to virtually any buyer. It did a brisk business with the Portuguese, Israelis, Argentines, and South Africans.

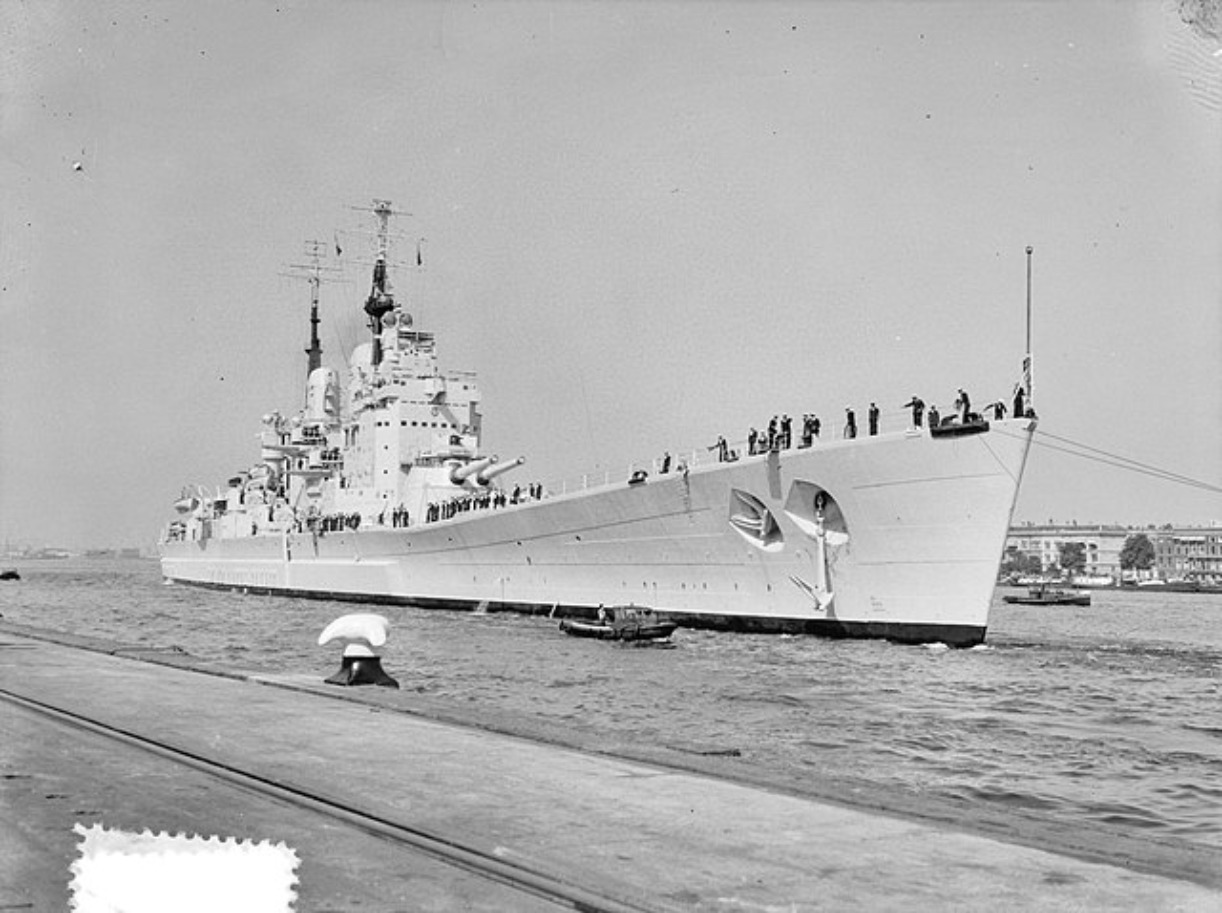

The

Force de Frappe, France’s nuclear strike assets, consisted of land-based tracked and rail launchers and submarine-carried nuclear missiles. (France’s three aircraft carriers could arm their strike fighters with nuclear missiles, but were not officially considered part of the Force, which remained a dyad.)

French intelligence had a hair-raising reputation the world over. The DGSE took on the role of extortionist, applying the necessary “incentives” for smaller countries to play within the boundaries set out by the politicians in Paris. French spies were killers, it was said, and could be hired to carry out the dirty work of shahs, board executives, and even the Soviet Politburo.

France’s very active space program was based at Korou in French Guyana and in the Algerian desert, with lesser operations in French Polynesia and leased facilities in the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville). In 2002, construction commenced on a space elevator in French Guyana that contributed to the construction and fitting out of U.N.S.

Unity. Though a founding participant in lunar settlement (a domed French Quarter is among the very few charms of Verne City), France focused mostly on “downward-looking” space applications via satellite operations, including deep ocean mapping.

Verne City, Luna, c. 2051

French support for the U.N. Mission to Alpha Centauri peaked in the 2040s, waxing as American focus was diverted to war at home, but many French politicians still viewed the project as a constant and painful reminder that there were other more potent actors than they on the world stage. France charged the U.N. heavily for access to its space launch infrastructure.

Two French mega-corporations, the Groupe Aéronautique Degére (GADE) and manufacturer of prime movers, Former Ciel, were major sub-contractors on the

Unity Project, together employing a workforce of almost 90,000 in Earth and space.

The major French “bequests” to the Mission were a large stock of surplus hand weapons (mostly ex-American) left over from its colonial wars and tens of thousands of older Minitel terminals for connection to Network Nodes.

Sources:

French paratroopers picture is from a History Channel

website article on the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.

Picture of future Paris is by French company Vincent Callebaut Architectures, shown on

archdaily in an article by Holly Giermann.

"Starscraper" name and picture are from "Starcraper #1" by miggysmallzXD on DeviantArt.

Desert cathedral is "Arizona Arcology - Earth That War" by nixoninevile on DeviantArt.

Picture of French troops in Mali is by Finbarr O'Reilly for

The New York Times.

Verne City picture is from

this article by Joshua Hawkins on BGR.

The character of Élodie was created by Strategos' Risk/MysticWind.

.jpg?1420687878)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/3JC24YVHCVENDAQFF74ZQPVWFU.png)