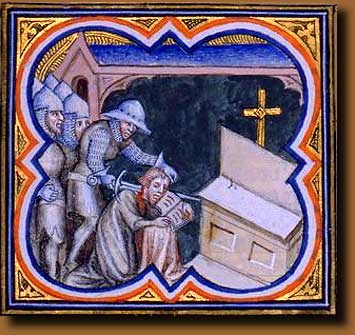

I thought I might follow Ciceronian's fine example and post an essay of my own. One of my classes this term is a survey of mediaeval European history, which is very standard and ho-hum and all that, except that it's taught as an in-depth study of one primary text: The Murder of Charles the Good, written by Galbert of Bruges in 1127. This is a really remarkable document, perhaps the first work of journalism, in which Galbert, a low-ranking clerical official, chronicles the conspiratorial murder of his beloved count, Saint Charles of Flanders, and the aftermath of that fateful event. It's noteworthy not only for his faithful record of events, but also for his use of a narrative filter, the frequent interjection of his own opinion into the story, his reflections on what the events could mean, and the generally broad picture it gives us of mediaeval life in northern Europe. He also talks a lot about God smiting people, and great famines in the land, and ominous bloody water turning up in ditches, so it makes for entertaining reading. I highly recommend it, if you're interested at all in that period of history.

Anyhow, my own little effort on the subject is a brief attempt to give an account of what and how Galbert and his peers thought about food. If you don't think this will interest you, I would stop reading right here, because I really don't talk about anything other than food, and the subject requires a fairly dry analysis. That being said, if you've always wanted to know something about food in the Middle Ages, I guess today's your lucky day. I've left the primary source citations in, in case anybody has the text and wants to read along, but I've omitted the secondary source citations.

__________________________________________________________________

The great Stoic Roman emperors always expressed their disdain for the sensual pleasure which their countrymen derived from gourmet foods and sophisticated banquets; well-to-do moderns since the Renaissance have probably exceeded the bons vivants of antiquity in their aspiration to feast upon fine foods. However, even the wealthiest Europeans in the interceding period had a very different conception of what they ate. Galbert of Bruges, in his work The Murder of Charles the Good, presents a unique perspective that demonstrates something of how all strata of mediaeval society regarded food. Beyond the mostly mundane picture which they lived with, Galbert's contemporaries also placed a symbolic importance on food, but they did so in a way that differs substantially from the modern approach to it.

Any investigation of the subject must begin with the elementary question of what the people of Galbert's time and place ate, and what meaning he made of those foods. To begin with, Galbert indicates that the basic categories of food people consumed were grain, meat, and cheese, and the editor confirms this (p. 143). Specifically, he gives an account of Fromold Junior fleeing into exile rather than reconcile himself with the traitors. Fromold first ate his final meal at home, and then distributed grain, cheese, and meat to his servants to support them in his absence (p. 143). The word distributed, and the fact that Fromold arrived at the transaction with the agreement of all concerned, indicates that these food items were given in sizeable quantities, and that they were thought of as bulk goods (p. 143).

Elsewhere, Galbert gives a different description of the basic foods: Therefore nothing but the church was left to the besieged except for the foodstuffs they had carried into the church, that is, wine and meat, flour, cheese, legumes, and the other necessities of life (p. 177). Wine and legumes (beans and peas) are added to the list. A likely reason is suggested by the fact that the besieged were of a higher social order than Fromold's servants. Wine was a somewhat expensive food that was not entirely basic: Galbert records that Count Charles had legislated a price ceiling of six pennies for a measure of wine, in order to stimulate trade of more useful goods (p. 88). Galbert describes the food of a person of yet higher social standing when he gives an account of Gervaise, the castellan, securing stores (mostly Charles') from the besieged church tower: there is good wine, mulled wine, bacon, roughly 2600 pounds of cheese, legumes, wheat flour, and a variety of high-quality cooking equipment, including iron bread pans (pp. 244-5). Clearly, the quality and variety of foods increased with social position.

The presence of specifically wheat flour in the count's stores described above is evidence of his privileged access to food. Wheat produced the greatest yield, and the best bread, of any grain, but its cultivation was also the riskiest and most difficult. Hence the common people typically substituted other grains, such as rye and barley. Only someone of the count's wealth could practically rely on wheat as a staple, because only he could absorb the risk of losing an entire harvest. In the time of famine that preceded the principal events of the text, Galbert records that Charles ordered bread to be made out of oats, and also forbade the production of beer, in order to make the best use of the available grain (pp. 87-8). Bread was the central mainstay of the diet in Flanders, as is evidenced by Galbert's numerous references to Charles' legislation concerning it: in addition to the measures already mentioned, the count ordered the size of loaves to be halved, in order to make them more generally affordable (p. 88); Charles' distribution of food to the poor primarily took the form of bread, and great quantities of it (p. 87).

Galbert also remarks that, during the famine, people ate meat because bread was completely lacking, which implies that bread was the standard, quotidian course of fare, and that its place in the diet could be filled only by an expensive commodity such as meat (p. 86). These unfortunate men became so desperate at their lack of bread that, though starving, they ventured the arduous journey to towns where they could buy it, often dying on the road (p. 86). The primary alternatives to grain-based bread were peas and beans, which could be made into rough breads, and which helpfully enriched the soil where they were grown. In addition to these features, the legumes produced their yield quickly, and so Charles ordered that one field of them be grown for every two of grains, in order to ensure a general supplement to the county's grain (p. 87).

Galbert's descriptions of the dietary practices in Flanders are consistent with the eating habits of other northern Europeans in his time period; the variations according to social status for which he gives evidence consist mostly in differences in the quality and quantity of the same basic foods; in other words, the count of Flanders largely ate the same kinds of things as his subjects of all strata, but had access to the best available foodstuffs of each kind, in a more consistently full and varied diet than his peasants could manage. This seems to have produced a common gastronomic culture, in which Galbert could talk about the same kinds of food, and similar attitudes towards it, with regard to his entire society. There was apparently no separate class of luxury food items, and no connoisseurs or dilettantes of epicurean pleasures.

An important feature of the hard exigencies of mediaeval life was the fact that food was viewed primarily as a quotidian fact of life, rather than as something of great interest in itself. People spent most of their time working to produce enough food to live, which strongly influenced their perception of it. Famine was an important enough phenomenon for Galbert to characterise it as a punishment of God, and to extensively describe its effects (pp. 85-6). Similarly, Galbert carefully notes when a person or persons lose their taste for food, and tends to ascribe it to supernatural causes. For example, the besieged traitors eventually suffer a curse from God that renders them unable to stand the smell and taste of any of their food and water:

By the marvelous dispensation of God it came about that their wine now smelled bad to those traitors, like a sour and tasteless drink and draught, their grain and bread tasted putrid, and the insipid water did them no good, so that they had almost succumbed to hunger and thirst, nauseated by the rotten taste and foul odor. (p. 241)

On another occasion, Count Thierry is struck by the spell of a sorceress; Galbert expressly remarks that as a result, the count loathed food and drink (p. 292). It is essential to notice that Galbert's usual treatment of foods is as necessities of life (p. 177), or as that which people consumed daily to sustain life (p. 218). The consistent use of this kind of language makes clear that food loomed large in the popular consciousness, but was not the object of particular interest.

In a related sense, food was also viewed as an important economic good. As has been seen, Count Charles took an active legislative interest in the large-scale production and selling of bread, legumes, beer, and wine; the vital importance of these matters to Galbert is clear in the fact that he directly mentions little else of Charles' legislation. Also significant are Galbert's several records of various foodstuffs as being important components of plundered treasure: he notes that the citizens of Bruges assaulted Thancmar's traitorous nephews to wrest from them quantities of grain and wine plundered from the house of the provost, Bertulf (p. 182-3), and also remarks the citizens' concern for foodstuffs which Fromold Junior was supposed to have placed in the count's house (p. 272). His careful list of Gervaise's requisitionings from the traitors has already been mentioned (p. 244-5). It is clear that in addition to (and because of) their role in daily survival, food items were valuable goods of economic worth and exchange.

All of this is not to suggest, however, that Galbert and his peers did not invest food with any significance beyond the mundane. For one, food had a strongly defined role as a social institution of the upper strata and their servants. A particularly important passage is Galbert's account of one of Charles' last meals. He has the count meeting with advisors while he eats, and then describes a wine-drinking event, in which the count's guests repeatedly request more wine, in a formal and perhaps ritual fashion (p. 107). Galbert twice uses the word grant to describe the count's gift of wine to his guests, and this, coupled with the formality of requesting the drink in rounds, suggests that wine-granting was a ritual of hospitality, perhaps offered by the very privileged. In another place, Galbert emphasises the significance of wine by recording Count William of Normandy's treatment of one Didier, who had been accused of treachery by Robert the Young and who was under suspicion, though not proven to be a traitor: William did not banish Didier, but yet his only action against him was that he had forbidden Didier, if by chance he should come to the court, to serve him wine, for he had been one of the servers of wine at the court of Charles (p. 265). Evidently, the serving of wine was a very important role, and it seems as though William felt his role as count to be threatened by having a possible traitor (whom Galbert names as innocent of wrongdoing, no less (p. 154)) involved in his wine-drinking events. Certainly, the editor comments that the importance of wine in the social life of the time is clear; mass drinking was probably the chief indoor diversion of the fighting class. Some formalities in the drinking ceremony seem to be observed (p. 107). So, wine at least was invested with a deeper meaning than mere status as a good for consumption.

Galbert also accords food some significance with regard to religion. As seen already, he has a notion of God using hunger as a punishment, both of Flanders as a whole (p. 84) and of the traitors (p. 241). More importantly, he sets a great deal of stock by holy feasts and fasts: he frequently gives the date relative to the nearest saint's feast day (pp. 253, 263, 266, 272), and mentions a universal fast, imposed by the priests as penance for a time of strife between William of Normandy and Count Thierry (p. 299). Galbert also quite indignantly accuses the priests of hypocrisy for their having permitted citizens to eat during Lent, and for having accepted gifts of money and food while prescribing an austere fast for the citizenry of Bruges (pp. 305-6). He evidently takes religious proscriptions on food very seriously, which is natural, given how mediaeval people tended to think of the year in terms of liturgical observances, usually occasion for festive release from their daily toil. However, Galbert also brings to the text certain superstitions regarding food: he takes care to describe, for example, the traitor Borsiard's having followed the custom of pagans and sorcerers by eating bread and drinking beer on Count Charles' tomb, the night of his murder (p. 263). He feels affronted by the sacrilegious nature of this act, apparently a kind of Saxon ritual (p. 263), precisely because he invests the food involved with a mystical meaning. Galbert's interest in the curse of the sorceress on Count Thierry has been noted; he also records the death of the sorceress by burning at the hands of Thierry's men (pp. 291-2). Thus there is evidently a second layer of significance to Galbert's treatment of food-- the religious or superstitious.

There readily emerges from Galbert's text a solid picture of how mediaeval people regarded food: mostly as a boring, basic fact of everyday existence, though a tremendously important one, but also as possessing symbolic value in various religious and cultural senses. Although moderns do not have a similarly mundane view of food, and take a much more sophisticated approach to it, it is interesting to note that the modern literary sensibility tends to preserve the more mystical element of the mediaeval's view as a rather romantic way to imbue food with meaning, with the result that the more arcane aspects of Galbert's gastronomic thought manage to strike the modern with a note of familiarity.

I may later post on other topics concerning Galbert as my coursework progresses, if anything interesting comes up.

Anyhow, my own little effort on the subject is a brief attempt to give an account of what and how Galbert and his peers thought about food. If you don't think this will interest you, I would stop reading right here, because I really don't talk about anything other than food, and the subject requires a fairly dry analysis. That being said, if you've always wanted to know something about food in the Middle Ages, I guess today's your lucky day. I've left the primary source citations in, in case anybody has the text and wants to read along, but I've omitted the secondary source citations.

__________________________________________________________________

The great Stoic Roman emperors always expressed their disdain for the sensual pleasure which their countrymen derived from gourmet foods and sophisticated banquets; well-to-do moderns since the Renaissance have probably exceeded the bons vivants of antiquity in their aspiration to feast upon fine foods. However, even the wealthiest Europeans in the interceding period had a very different conception of what they ate. Galbert of Bruges, in his work The Murder of Charles the Good, presents a unique perspective that demonstrates something of how all strata of mediaeval society regarded food. Beyond the mostly mundane picture which they lived with, Galbert's contemporaries also placed a symbolic importance on food, but they did so in a way that differs substantially from the modern approach to it.

Any investigation of the subject must begin with the elementary question of what the people of Galbert's time and place ate, and what meaning he made of those foods. To begin with, Galbert indicates that the basic categories of food people consumed were grain, meat, and cheese, and the editor confirms this (p. 143). Specifically, he gives an account of Fromold Junior fleeing into exile rather than reconcile himself with the traitors. Fromold first ate his final meal at home, and then distributed grain, cheese, and meat to his servants to support them in his absence (p. 143). The word distributed, and the fact that Fromold arrived at the transaction with the agreement of all concerned, indicates that these food items were given in sizeable quantities, and that they were thought of as bulk goods (p. 143).

Elsewhere, Galbert gives a different description of the basic foods: Therefore nothing but the church was left to the besieged except for the foodstuffs they had carried into the church, that is, wine and meat, flour, cheese, legumes, and the other necessities of life (p. 177). Wine and legumes (beans and peas) are added to the list. A likely reason is suggested by the fact that the besieged were of a higher social order than Fromold's servants. Wine was a somewhat expensive food that was not entirely basic: Galbert records that Count Charles had legislated a price ceiling of six pennies for a measure of wine, in order to stimulate trade of more useful goods (p. 88). Galbert describes the food of a person of yet higher social standing when he gives an account of Gervaise, the castellan, securing stores (mostly Charles') from the besieged church tower: there is good wine, mulled wine, bacon, roughly 2600 pounds of cheese, legumes, wheat flour, and a variety of high-quality cooking equipment, including iron bread pans (pp. 244-5). Clearly, the quality and variety of foods increased with social position.

The presence of specifically wheat flour in the count's stores described above is evidence of his privileged access to food. Wheat produced the greatest yield, and the best bread, of any grain, but its cultivation was also the riskiest and most difficult. Hence the common people typically substituted other grains, such as rye and barley. Only someone of the count's wealth could practically rely on wheat as a staple, because only he could absorb the risk of losing an entire harvest. In the time of famine that preceded the principal events of the text, Galbert records that Charles ordered bread to be made out of oats, and also forbade the production of beer, in order to make the best use of the available grain (pp. 87-8). Bread was the central mainstay of the diet in Flanders, as is evidenced by Galbert's numerous references to Charles' legislation concerning it: in addition to the measures already mentioned, the count ordered the size of loaves to be halved, in order to make them more generally affordable (p. 88); Charles' distribution of food to the poor primarily took the form of bread, and great quantities of it (p. 87).

Galbert also remarks that, during the famine, people ate meat because bread was completely lacking, which implies that bread was the standard, quotidian course of fare, and that its place in the diet could be filled only by an expensive commodity such as meat (p. 86). These unfortunate men became so desperate at their lack of bread that, though starving, they ventured the arduous journey to towns where they could buy it, often dying on the road (p. 86). The primary alternatives to grain-based bread were peas and beans, which could be made into rough breads, and which helpfully enriched the soil where they were grown. In addition to these features, the legumes produced their yield quickly, and so Charles ordered that one field of them be grown for every two of grains, in order to ensure a general supplement to the county's grain (p. 87).

Galbert's descriptions of the dietary practices in Flanders are consistent with the eating habits of other northern Europeans in his time period; the variations according to social status for which he gives evidence consist mostly in differences in the quality and quantity of the same basic foods; in other words, the count of Flanders largely ate the same kinds of things as his subjects of all strata, but had access to the best available foodstuffs of each kind, in a more consistently full and varied diet than his peasants could manage. This seems to have produced a common gastronomic culture, in which Galbert could talk about the same kinds of food, and similar attitudes towards it, with regard to his entire society. There was apparently no separate class of luxury food items, and no connoisseurs or dilettantes of epicurean pleasures.

An important feature of the hard exigencies of mediaeval life was the fact that food was viewed primarily as a quotidian fact of life, rather than as something of great interest in itself. People spent most of their time working to produce enough food to live, which strongly influenced their perception of it. Famine was an important enough phenomenon for Galbert to characterise it as a punishment of God, and to extensively describe its effects (pp. 85-6). Similarly, Galbert carefully notes when a person or persons lose their taste for food, and tends to ascribe it to supernatural causes. For example, the besieged traitors eventually suffer a curse from God that renders them unable to stand the smell and taste of any of their food and water:

By the marvelous dispensation of God it came about that their wine now smelled bad to those traitors, like a sour and tasteless drink and draught, their grain and bread tasted putrid, and the insipid water did them no good, so that they had almost succumbed to hunger and thirst, nauseated by the rotten taste and foul odor. (p. 241)

On another occasion, Count Thierry is struck by the spell of a sorceress; Galbert expressly remarks that as a result, the count loathed food and drink (p. 292). It is essential to notice that Galbert's usual treatment of foods is as necessities of life (p. 177), or as that which people consumed daily to sustain life (p. 218). The consistent use of this kind of language makes clear that food loomed large in the popular consciousness, but was not the object of particular interest.

In a related sense, food was also viewed as an important economic good. As has been seen, Count Charles took an active legislative interest in the large-scale production and selling of bread, legumes, beer, and wine; the vital importance of these matters to Galbert is clear in the fact that he directly mentions little else of Charles' legislation. Also significant are Galbert's several records of various foodstuffs as being important components of plundered treasure: he notes that the citizens of Bruges assaulted Thancmar's traitorous nephews to wrest from them quantities of grain and wine plundered from the house of the provost, Bertulf (p. 182-3), and also remarks the citizens' concern for foodstuffs which Fromold Junior was supposed to have placed in the count's house (p. 272). His careful list of Gervaise's requisitionings from the traitors has already been mentioned (p. 244-5). It is clear that in addition to (and because of) their role in daily survival, food items were valuable goods of economic worth and exchange.

All of this is not to suggest, however, that Galbert and his peers did not invest food with any significance beyond the mundane. For one, food had a strongly defined role as a social institution of the upper strata and their servants. A particularly important passage is Galbert's account of one of Charles' last meals. He has the count meeting with advisors while he eats, and then describes a wine-drinking event, in which the count's guests repeatedly request more wine, in a formal and perhaps ritual fashion (p. 107). Galbert twice uses the word grant to describe the count's gift of wine to his guests, and this, coupled with the formality of requesting the drink in rounds, suggests that wine-granting was a ritual of hospitality, perhaps offered by the very privileged. In another place, Galbert emphasises the significance of wine by recording Count William of Normandy's treatment of one Didier, who had been accused of treachery by Robert the Young and who was under suspicion, though not proven to be a traitor: William did not banish Didier, but yet his only action against him was that he had forbidden Didier, if by chance he should come to the court, to serve him wine, for he had been one of the servers of wine at the court of Charles (p. 265). Evidently, the serving of wine was a very important role, and it seems as though William felt his role as count to be threatened by having a possible traitor (whom Galbert names as innocent of wrongdoing, no less (p. 154)) involved in his wine-drinking events. Certainly, the editor comments that the importance of wine in the social life of the time is clear; mass drinking was probably the chief indoor diversion of the fighting class. Some formalities in the drinking ceremony seem to be observed (p. 107). So, wine at least was invested with a deeper meaning than mere status as a good for consumption.

Galbert also accords food some significance with regard to religion. As seen already, he has a notion of God using hunger as a punishment, both of Flanders as a whole (p. 84) and of the traitors (p. 241). More importantly, he sets a great deal of stock by holy feasts and fasts: he frequently gives the date relative to the nearest saint's feast day (pp. 253, 263, 266, 272), and mentions a universal fast, imposed by the priests as penance for a time of strife between William of Normandy and Count Thierry (p. 299). Galbert also quite indignantly accuses the priests of hypocrisy for their having permitted citizens to eat during Lent, and for having accepted gifts of money and food while prescribing an austere fast for the citizenry of Bruges (pp. 305-6). He evidently takes religious proscriptions on food very seriously, which is natural, given how mediaeval people tended to think of the year in terms of liturgical observances, usually occasion for festive release from their daily toil. However, Galbert also brings to the text certain superstitions regarding food: he takes care to describe, for example, the traitor Borsiard's having followed the custom of pagans and sorcerers by eating bread and drinking beer on Count Charles' tomb, the night of his murder (p. 263). He feels affronted by the sacrilegious nature of this act, apparently a kind of Saxon ritual (p. 263), precisely because he invests the food involved with a mystical meaning. Galbert's interest in the curse of the sorceress on Count Thierry has been noted; he also records the death of the sorceress by burning at the hands of Thierry's men (pp. 291-2). Thus there is evidently a second layer of significance to Galbert's treatment of food-- the religious or superstitious.

There readily emerges from Galbert's text a solid picture of how mediaeval people regarded food: mostly as a boring, basic fact of everyday existence, though a tremendously important one, but also as possessing symbolic value in various religious and cultural senses. Although moderns do not have a similarly mundane view of food, and take a much more sophisticated approach to it, it is interesting to note that the modern literary sensibility tends to preserve the more mystical element of the mediaeval's view as a rather romantic way to imbue food with meaning, with the result that the more arcane aspects of Galbert's gastronomic thought manage to strike the modern with a note of familiarity.

I may later post on other topics concerning Galbert as my coursework progresses, if anything interesting comes up.