You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Chronicles of Khan

- Thread starter Sandman2003

- Start date

Sandman2003

Prince

Yes, Demo - since we are pushing science, and have a very sprawling empire, Demo gives the least corruption and is therefore the best for science. However, it is very fagile during combat - something to keep me on my toes. I can't really afford to let the AI civs 'accidentally' capture or recapture any cities!

Sandman2003

Prince

Chapter Nineteen – The American War

At the time of the war declaration, America had 24 cities, making it about 40% larger than the Scandinavians had been. Additionally, the Americans had spent the intervening years since their last military action feverously pursuing scientific parity with the rest of the world. The Mongols had failed in the planting spy attempt, and so were unaware as to whether the Americans yet had rifles or not, but it was clear that they were close. Also, unlike the Scandinavians with only three completely isolated and totally corrupt cities amongst the Mongolians, the Americans had no less than eight cities dotted about in former Germany, China and India, predominantly.

These eight American cities were much closer to the American core than the Scandinavian cities had been to Scandinavia. In addition, many of them were connected with each other, resulting in a greater combined menace. In many ways these eight cities represented a critical strategic risk to the Mongolian war plans, especially given the adverse manner in which the Mongolian public reacted to bad war news. They also massively extended the Mongolian front line with America.

On the other hand, Subedei had been planning for a campaign against the Americans for some time, and as technology and war techniques continued to improve the plan was steadily refined to take into account the these new advances. In particular, the strategic railnet meant that Subedei could rapidly deliver troops to every single border city of the Americans. With the might of the cavalry armies, and the up-powered keshik armies, combined with huge numbers of cavalry, Subedei’s plan called for a blitz on America the like of which had never been seen before!

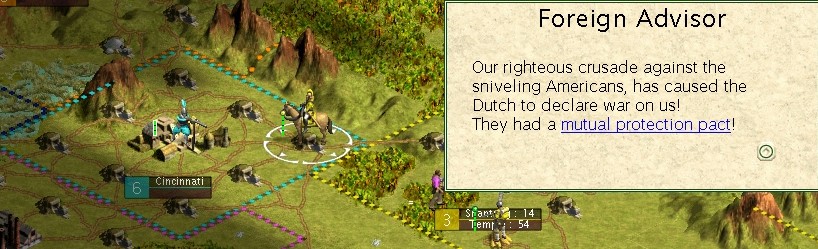

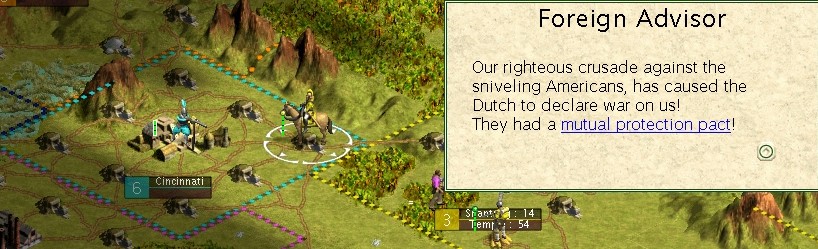

Of course, there was one minor oversight in this plan, the Dutch-American Pact was still in full force, so as soon as Mongolian troops entered American territory by Cincinnati, the Dutch were dragged in to the conflict as well.

Now the Dutch were the second most technologically advanced nation on the planet, and definitely possessed both rifles and cavalries to spare. They also added another 14 cities to the productive might of the alliance against the Mongols, and had four cities bordering Mongolian territory, although their core was pretty much as far from Mongolia as any civilisation could get. Certainly the previous concern about losing the vast annual payment from the Dutch was no longer present, as current payments were far smaller than the original sum, so it was only the Dutch military that represented a concern.

A decision was quickly made in the Khan’s war council chambers. The Dutch would simply be held at bay, at first, while the annoying Americans were crushed, then the full force of Mongolia would be applied in earnest against the Dutch! Holding them at bay meant beefing up the bordering cities with infantry, a unit that remained in the sole ownership of the Mongols.

And so, Subedei’s plan was left virtually unchanged as he launched the most massive attack upon the Americans, just at the dawn of the fifteenth century. Cincinnati felt the brunt first, and although painful due to the Dutch declaration, and due to costing a cavalry division, a musket and a pike division of the Americans were destroyed, claiming the city.

Denver was next. Two cavalry divisions smashed through the defending pike and spear divisions. Then it was on to Heidelberg. The two defending pike divisions could not cope with the two cavalry division onslaught. At Dallas the defences were weaker, consisting of only a pike and a spear division, and these did not trouble the assault. The hill city of Baltimore was overrun by Keshik divisions, again without Mongol loss. Cleveland’s three pike divisions fell to the seventh cavalry army. Lahore’s two musket divisions, claimed a cavalry division, but were still swept aside. And at Hangchow, the two musket divisions also claimed a cavalry, but generated a new Mongolian leader, and inevitably fell to the Mongol onslaught.

This first massive push deprived America of all its satellite holdings, leaving only the main core, and Subedei was only just starting his offensive.

The city of Krasnoyarsk, formerly Russian, then Byzantine, and most recently American, soon became Mongolian as the fifth cavalry army destroyed a musket and a spear division. Then it was up the coast. Tver fell to the third keshik army, losing a musket and a pike division in the process. With workers connecting up the Mongolian rail system to the borders of the new holdings, Kansas City was brought within reach of the Mongolian wrath. Here the fourth cavalry army was employed to smash the two pike division defence.

At Miami, Tolui’s cavalry army crushed an elite pike division, then a musket division, but defenders still remained. With the railnet in place it was a simple matter to call for reinforcements, and a single further cavalry division was soon on the scene destroying another pike division to take the city.

Philadelphia was able to accessed from former China, but proved a little more resistant than some, taking the combined efforts of Kublai’s keshik army and two divisions of cavalry to rout the defence. From Philadelphia, Washington could just be reached, and was assaulted with two cavalry armies and a keshik army.

The battle for Chicago cost the Mongols a cavalry division, but the city soon fell to the might of two keshik armies and a further two cavalry divisions.

After railing was completed through Kansas city, the coastal onslaught continued at Houston. Though the American defence at Houston proved resolute and destroyed one attacking cavalry division, it could not withstand the onslaught of a further three cavalry divisions.

These massive gains revealed American units waiting patiently in the core for orders. Subedei took advantage of this situation by destroying a lone knight division, but in the process losing a keshik division.

After still more railing, the last American city of Subedei’s blitz is brought to within range of the Mongols. The defenders at Boston fight bravely, and account for fully two cavalry divisions in the process, but even they are unable to prevent the power of the Mongols claiming the city. These huge strides into American territory reveal many American units still awaiting orders. The Mongols are only able to dispatch one further knight division and a spear division with their remaining offensive units, but in the process yet another leader is produced from the field of battle.

The Americans lost 17 of their 24 cities in this one massive blitz of Subedei’s. That represents over 70% of their power. With the huge Mongolian workforce tasked with bringing rails to these new conquests, infantry divisions were rushed to the front lines. Subedei could ill-afford to take chances with the fickle Mongolian populace.

The American generals of course tried to fight back. In the process they actually managed to kill a mighty infantry division, proving that even these great defence units are not invincible. Three cavalry divisions also perished, but the cost to American military was much larger, and most important of all, none of these counter-attacks was able to breech the Mongolian Defence around any of the newly captured cities.

The year 1405AD sees the war continue, but this year there is no blitz. The American forces are too plentiful, and pose an ever present threat to the newly captured cities. In addition, many units are forced to rest up owing to the weariness of the glorious battles of the opening conflict. Furthermore, the Dutch made use of the Incan territory to move numerous cavalry divisions within range of a possible strike at New Koningsberg, just north of their cities on the above map.

Subedei will not settle for no progress, however, and so as thousands of Americans perished in the battles arouns Buffalo, inevitably it became time for the town itself to face the might of Subedei’s armies. The hapless resistors at Buffalo are also unable to stem the tide of Mongolian force.

The tundra of New Orleans, however, does not prove as simple for Subedei, and fully two divisions of Mongolian troops perish during the onslaught, soaking the ice, red. But these numbers are just insufficient to stop the Mongolian war machine, and so New Orleans is also liberated from the Americans.

In an effort to halt the progress of the Dutch forces through Incan territory, Yeh-lu signs a trade embargo with the Incans against the Dutch, even though it takes the bribe of an ongoing spice supply to make the deal happen.

1410AD rolled around with the Americans down to five cities. The American counter-attack is reduced to being feeble at best. Seattle falls first, only requiring a single army. At Atlanta, due to distance, and a stronger American will, it takes no less than four armies to crush the defence. Then it is the turn of San Francisco, and very little resistance is encountered there. St Louis also falls easily, once the railnet is built up to the latest borders.

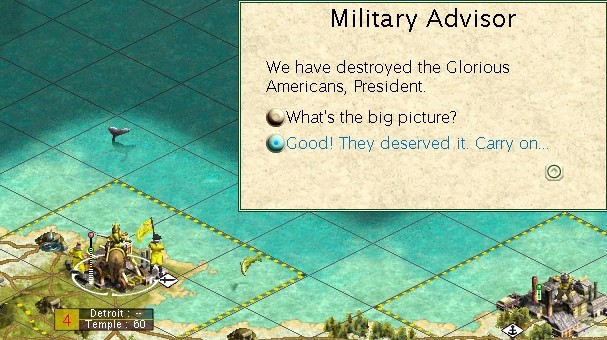

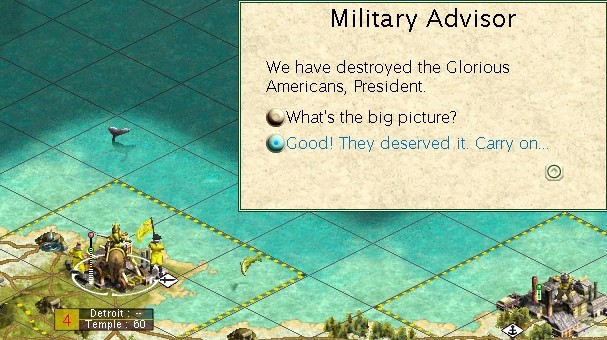

Finally, the Americans are left with the northern tundra city of Detroit. Only the speed of the cavalry armies is sufficient to reach Detroit, and at first they come up short. Detroit has one more defender than Subedei has cavalry armies left. But there is a solution. The recent leaders had formed armies, but had not had units added to make them useful, yet. Now with the need so plainly there, another army is completed with cavalry and dispatched to the front immediately. The power of a new cavalry army against the last defending American unit is no match at all, and Detroit falls.

Subedei had achieved his dream. The Americans were crushed in just ten years in the most brutally efficient military campaign yet undertaken. However, threats to the Mongolian security still remained. The Dutch were pressing at New Koningsberg, and fully intended to be true to the spirit of their pact, even with the complete defeat of their ally. The Mongolian war-machine turned to face the power of the Dutch!

At the time of the war declaration, America had 24 cities, making it about 40% larger than the Scandinavians had been. Additionally, the Americans had spent the intervening years since their last military action feverously pursuing scientific parity with the rest of the world. The Mongols had failed in the planting spy attempt, and so were unaware as to whether the Americans yet had rifles or not, but it was clear that they were close. Also, unlike the Scandinavians with only three completely isolated and totally corrupt cities amongst the Mongolians, the Americans had no less than eight cities dotted about in former Germany, China and India, predominantly.

These eight American cities were much closer to the American core than the Scandinavian cities had been to Scandinavia. In addition, many of them were connected with each other, resulting in a greater combined menace. In many ways these eight cities represented a critical strategic risk to the Mongolian war plans, especially given the adverse manner in which the Mongolian public reacted to bad war news. They also massively extended the Mongolian front line with America.

On the other hand, Subedei had been planning for a campaign against the Americans for some time, and as technology and war techniques continued to improve the plan was steadily refined to take into account the these new advances. In particular, the strategic railnet meant that Subedei could rapidly deliver troops to every single border city of the Americans. With the might of the cavalry armies, and the up-powered keshik armies, combined with huge numbers of cavalry, Subedei’s plan called for a blitz on America the like of which had never been seen before!

Of course, there was one minor oversight in this plan, the Dutch-American Pact was still in full force, so as soon as Mongolian troops entered American territory by Cincinnati, the Dutch were dragged in to the conflict as well.

Now the Dutch were the second most technologically advanced nation on the planet, and definitely possessed both rifles and cavalries to spare. They also added another 14 cities to the productive might of the alliance against the Mongols, and had four cities bordering Mongolian territory, although their core was pretty much as far from Mongolia as any civilisation could get. Certainly the previous concern about losing the vast annual payment from the Dutch was no longer present, as current payments were far smaller than the original sum, so it was only the Dutch military that represented a concern.

A decision was quickly made in the Khan’s war council chambers. The Dutch would simply be held at bay, at first, while the annoying Americans were crushed, then the full force of Mongolia would be applied in earnest against the Dutch! Holding them at bay meant beefing up the bordering cities with infantry, a unit that remained in the sole ownership of the Mongols.

And so, Subedei’s plan was left virtually unchanged as he launched the most massive attack upon the Americans, just at the dawn of the fifteenth century. Cincinnati felt the brunt first, and although painful due to the Dutch declaration, and due to costing a cavalry division, a musket and a pike division of the Americans were destroyed, claiming the city.

Denver was next. Two cavalry divisions smashed through the defending pike and spear divisions. Then it was on to Heidelberg. The two defending pike divisions could not cope with the two cavalry division onslaught. At Dallas the defences were weaker, consisting of only a pike and a spear division, and these did not trouble the assault. The hill city of Baltimore was overrun by Keshik divisions, again without Mongol loss. Cleveland’s three pike divisions fell to the seventh cavalry army. Lahore’s two musket divisions, claimed a cavalry division, but were still swept aside. And at Hangchow, the two musket divisions also claimed a cavalry, but generated a new Mongolian leader, and inevitably fell to the Mongol onslaught.

This first massive push deprived America of all its satellite holdings, leaving only the main core, and Subedei was only just starting his offensive.

The city of Krasnoyarsk, formerly Russian, then Byzantine, and most recently American, soon became Mongolian as the fifth cavalry army destroyed a musket and a spear division. Then it was up the coast. Tver fell to the third keshik army, losing a musket and a pike division in the process. With workers connecting up the Mongolian rail system to the borders of the new holdings, Kansas City was brought within reach of the Mongolian wrath. Here the fourth cavalry army was employed to smash the two pike division defence.

At Miami, Tolui’s cavalry army crushed an elite pike division, then a musket division, but defenders still remained. With the railnet in place it was a simple matter to call for reinforcements, and a single further cavalry division was soon on the scene destroying another pike division to take the city.

Philadelphia was able to accessed from former China, but proved a little more resistant than some, taking the combined efforts of Kublai’s keshik army and two divisions of cavalry to rout the defence. From Philadelphia, Washington could just be reached, and was assaulted with two cavalry armies and a keshik army.

The battle for Chicago cost the Mongols a cavalry division, but the city soon fell to the might of two keshik armies and a further two cavalry divisions.

After railing was completed through Kansas city, the coastal onslaught continued at Houston. Though the American defence at Houston proved resolute and destroyed one attacking cavalry division, it could not withstand the onslaught of a further three cavalry divisions.

These massive gains revealed American units waiting patiently in the core for orders. Subedei took advantage of this situation by destroying a lone knight division, but in the process losing a keshik division.

After still more railing, the last American city of Subedei’s blitz is brought to within range of the Mongols. The defenders at Boston fight bravely, and account for fully two cavalry divisions in the process, but even they are unable to prevent the power of the Mongols claiming the city. These huge strides into American territory reveal many American units still awaiting orders. The Mongols are only able to dispatch one further knight division and a spear division with their remaining offensive units, but in the process yet another leader is produced from the field of battle.

The Americans lost 17 of their 24 cities in this one massive blitz of Subedei’s. That represents over 70% of their power. With the huge Mongolian workforce tasked with bringing rails to these new conquests, infantry divisions were rushed to the front lines. Subedei could ill-afford to take chances with the fickle Mongolian populace.

The American generals of course tried to fight back. In the process they actually managed to kill a mighty infantry division, proving that even these great defence units are not invincible. Three cavalry divisions also perished, but the cost to American military was much larger, and most important of all, none of these counter-attacks was able to breech the Mongolian Defence around any of the newly captured cities.

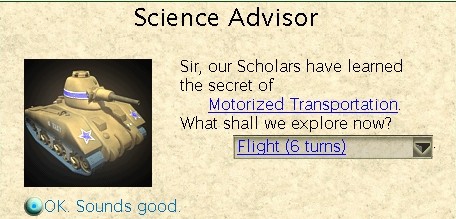

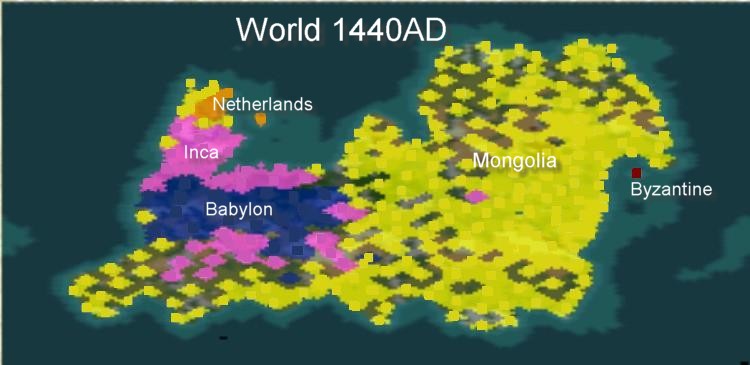

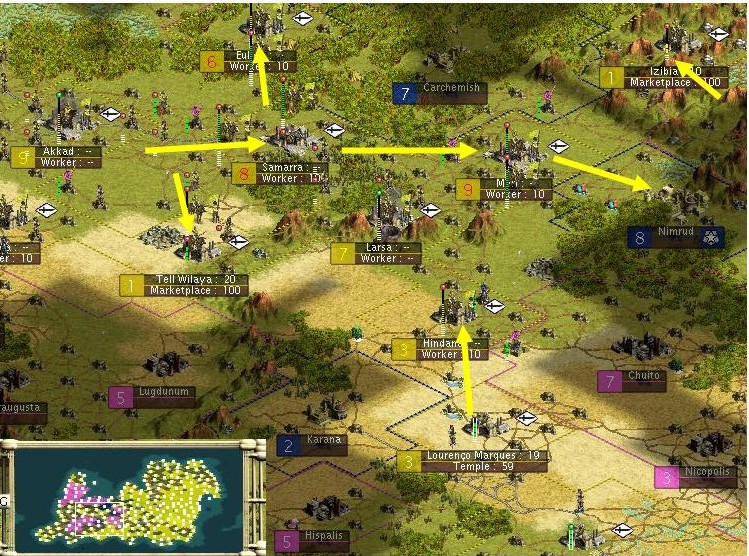

The year 1405AD sees the war continue, but this year there is no blitz. The American forces are too plentiful, and pose an ever present threat to the newly captured cities. In addition, many units are forced to rest up owing to the weariness of the glorious battles of the opening conflict. Furthermore, the Dutch made use of the Incan territory to move numerous cavalry divisions within range of a possible strike at New Koningsberg, just north of their cities on the above map.

Subedei will not settle for no progress, however, and so as thousands of Americans perished in the battles arouns Buffalo, inevitably it became time for the town itself to face the might of Subedei’s armies. The hapless resistors at Buffalo are also unable to stem the tide of Mongolian force.

The tundra of New Orleans, however, does not prove as simple for Subedei, and fully two divisions of Mongolian troops perish during the onslaught, soaking the ice, red. But these numbers are just insufficient to stop the Mongolian war machine, and so New Orleans is also liberated from the Americans.

In an effort to halt the progress of the Dutch forces through Incan territory, Yeh-lu signs a trade embargo with the Incans against the Dutch, even though it takes the bribe of an ongoing spice supply to make the deal happen.

1410AD rolled around with the Americans down to five cities. The American counter-attack is reduced to being feeble at best. Seattle falls first, only requiring a single army. At Atlanta, due to distance, and a stronger American will, it takes no less than four armies to crush the defence. Then it is the turn of San Francisco, and very little resistance is encountered there. St Louis also falls easily, once the railnet is built up to the latest borders.

Finally, the Americans are left with the northern tundra city of Detroit. Only the speed of the cavalry armies is sufficient to reach Detroit, and at first they come up short. Detroit has one more defender than Subedei has cavalry armies left. But there is a solution. The recent leaders had formed armies, but had not had units added to make them useful, yet. Now with the need so plainly there, another army is completed with cavalry and dispatched to the front immediately. The power of a new cavalry army against the last defending American unit is no match at all, and Detroit falls.

Subedei had achieved his dream. The Americans were crushed in just ten years in the most brutally efficient military campaign yet undertaken. However, threats to the Mongolian security still remained. The Dutch were pressing at New Koningsberg, and fully intended to be true to the spirit of their pact, even with the complete defeat of their ally. The Mongolian war-machine turned to face the power of the Dutch!

Sandman2003

Prince

Chapter Twenty – The Second Great Railing Project

The Dutch represented a logistical nightmare for the Mongols. Though four cities were within relatively easy reach of the Mongolian forces, the rest were either at the furthest end of the planet, or even worse, were off the mainland altogether. Subedei, however, was not perturbed by this revelation, pointing to how the first great rail project had shown the way.

There was a more pressing danger posed by the Dutch forces. While the Mongolian population rejoiced over the crushing victory against the Americans, the Dutch had advanced their strong rifle divisions into the mountains by New Koningsberg. The citizens of New Koningsberg were very aware that the bulk of the troops were still in the Ameruican lands, and so even with the power of infantry divisions protecting the city, there was a concern with the closeness of this Dutch presence.

However, Subedei had reserved the artillery. There had been no need for this weapon against the defenders that America had been able to field. However, Dutch rifle divisions hiding in the mountains were a different story, and artillery was rushed to the front to dispense with the imminent threat. With the numbers of these powerful bombardment tools that Subedei had at his disposal, the Dutch troops fell into disarray. It was then easy pickings for cavalry divisions to charge into the mountains and finish off the Dutch resistance. In all four divisions of rifles and one division of longbows were slaughtered.

This did not end the Dutch offensive, however, as tens of thousands of Dutch troops, mainly in rifle divisions, were on the march through the jungles of former Germany towards the Mongol city of Berlin.

As the year 1415AD was heralded in, Subedei was able to turn the considerable might of the Mongol military machine to directly face the Dutch, and the Mongol counter-offensive began. The Dutch had been using the city of Frankfurt as their staging point to launch their attacks against the Mongols, so it was only natural that this city become the first target for Subedei. Following a heave artillery barrage, Frankfurt was then charged by cavalry divisions. The stunned defenders were no match for these Mongolian divisions, and in the process of liberating Frankfurt, Jochi stepped forward as a new Mongolian military leader.

Then the Mongolian artillery was brought to bear upon the Dutch advance in the jungle. After another heavy bombardment, a mix of cavalry divisions and even infantry divisions were used on the attack to wipe out a full 130,000 Dutch invaders.

The Dutch response was starting to weaken. A smaller troop advanced on Frankfurt in an attempt to liberate this former Dutch city. In a further act of desperation, the Dutch signed a mutual protection pact with the one city state, Byzantines. a Pact that was really of no benefit to either civilisation. It did however result in the Mongols now facing a second foe, even if the danger from that quarter was almost non-existent.

In all this war excitement, the sages were met with a somewhat muted response to their demonstration of the secrets of Mass Production. However, their new research goal, motorised transport, and the ultimate tool that this was thought to deliver to the battlefield was warmly greeted. So once again the sages were granted the full funding necessary to pursue this latest task.

Then as 1420AD dawned, Subedei had access to his fully healed armies to strike the Dutch with. At Novosibirsk, the eight cavalry army dispensed with two rifle divisions, and Chagatai’s keshik army eliminated the third and final rifle division to prise this city from the Dutch.

In the south by the Great Dividing Range, the Dutch had previously formed a small colony called Delft. This year was to be its swansong as it was first hit by a cavalry army, and then finished off by the seventh cavalry army. Two rifle divisions were accounted for in the process.

By Frankfurt, the new Dutch advance is again shelled by the artillery, and then attacked by elite cavalry divisions, spawning another leader for the Mongols. The leader was quickly whisked home to Karakorum to establish another currently empty army.

It was fully 1425AD, before the last Dutch city in the west was within range of the Mongols. The now tried and tested method of artillery bombardment followed by cavalry charge quickly dislodged the two rifle divisions of defenders.

This action cleared the Dutch presence from the east altogether. However, now the Mongol military machine had to face up to the logistical nightmare that the western part of the Dutch empire represented. The Netherlands were isolated in the far north west of the continent, with the full breadth of Babylonia, and the Incan territory at its widest part separating the Mongols and Dutch nations. What’s more, neither the backward Babylonians, nor the Incans had an established rail net, so getting forces to the front, and then reinforcements afterwards was going to be a major problem.

The first great railing project had given the Mongols an idea. This time however, the distance was far greater. The second great railing project was commenced, joining up where the first had left off. In addition, because the railing effort was so reliant on the existing road network, a direct path for the rails could not be used. The railroad had to follow this winding road passage.

In any event, with the Khan’s full backing, many worker crews left the Mongolian core and started work on this most ambitious task. The first phase of the project extended right through Babylon and into Inca, and comprised fully 2800 kilometres of track. It also brought the Mongols right up to the new advanced guard of the Dutch comprising fully 180,000 soldiers!

These troops were caught unawares. With the speed of the rail system in place, Subedei was able to ferry his well rested armies directly to the front, and strike at these rifle divisions of the enemy. As the force was a mix of rifles and longbow divisions, the armies dispensed with the rifles and the cavalry cleaned up the longbows. In this way, the Mongols suffered minimum casualties, but this large force was decimated, staining the Tiwanaku forests a deep red.

In 1430AD the phase two of the track was completed. A further 1200 kilometres of track brought it to the mountains south of the Netherland city of Groningen. Three hundred kilometres extended west to the lone Dutch city of Eindhoven as well, and so the final assault on the Netherlands could begin.

The city of Groningen was struck first. After an extensive artillery barrage, cavalry moved in to clean up the rest. This time though, the Mongols were attacking the heart of the Dutch nation, and so the defence was that more resolute. In spite of the fierce artillery barrage, the defence remained determined, and claimed two full cavalry divisions. But the loss to the Dutch was far worse, as five divisions of rifles were crushed, and even Groningen fell.

Eindhoven was next. It took two cavalry armies and a cavalry division to smash through the four divisions of rifles and one longbow division guarding the city, and claim it for the Mongols.

Then the Mongols moved into the very heart of the Netherlands. The important harbour city of Maastricht was next. Maastricht was important because it provided access to the Dutch Island city of Holwerd, and unlike the Byzantine’s island city, this island was large enough to land an invasion force next to the city, and so it was not the invulnerable fortress that the Byzantine city currently represented. Maastricht, however, was over the hills, thus limiting the range of the attacking units. A small amount of artillery was yet unutilised, so a small preliminary bombardment preceded the action here as two keshik armies and one cavalry army mounted the rise and assaulted the city, destroying four rifle divisions in the process. Maastricht fell.

Another three hundred kilometres of railing brought the Mongols over to the west coast, and within reach of the city of Rotterdam. A cavalry army and a keshik army combined to kill the four rifle divisions in this city.

More railing brought Amsterdam within range, however, Subedei was once again running short on armies. He decided to utilise one of the spare armies in Karakorum now, instead of waiting for the super weapon of the future, and so filled the ninth cavalry army. Due to distance, Amsterdam required no less than five armies, but eventually fell, and with it the ancient wonders of the Great Lighthouse and the Colossus fell into Mongolian hands.

Subedei was ever keen to continue his offensive, and so he created the tenth cavalry army, and rushed it into action at Haarlem. Single handedly this new army destroyed three rifle divisions to capture the city.

This last push has reduced the Dutch to their three mainland cities and their island city. The Dutch also have twelve divisions in Incan territory near the Mongols’ new rail infrastructure. Chebe advised not to even bother with these units. The Dutch command structure would soon be in tatters and the threat from these units would them dissipate. So instead of launching any offensives against them, the infrastructure and worker crews are protected by strong infantry divisions and the Dutch are invited to do their worst.

1435AD is a quiet year on the military front. Numerous Mongolian units need a well earned rest and recovery time, and the final Mongolian cities are spread far from the borders. An advance is made on the remaining three, but only at The Hague, does battle commence. Due to the distance, it takes a full four cavalry armies to bridge the gap and attack, destroying the three rifle divisions, and capturing this one city.

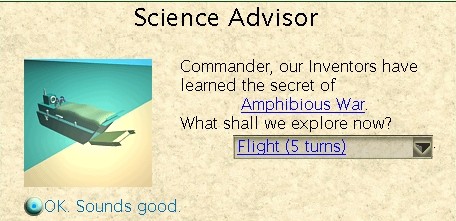

However the year is memorable for another much more important region. The sages were to return once again to the Khan’s court with news of a new announcement. This time they were very warmly greeted, especially when they revealed the new toy to the generals. It met and far exceeded their expectations.

The celebrations were exuberant to say the least. When the partying was finally over, the sages were authorised to pursue amphibious warfare, again with generous funding. Meanwhile, all military builds across the entire huge Mongolian empire were swapped immediately to this new devastating tool. Furthermore, this new weapon inspired the Khan to reconsider his world view. It was clear that the world remained hostile towards the Mongols, and with each new foe being vanquished, the resentment of the remaining nations grew. It seemed inevitable that when the Dutch were shortly brought under control, the huge borders of the Mongols would be at risk from either the Babylonians or the Incans over what-ever slight infraction they deemed to have occurred. The only path to a peaceful future appeared to be after a short period of all out war.

This the Khan pondered at some length.

The Dutch represented a logistical nightmare for the Mongols. Though four cities were within relatively easy reach of the Mongolian forces, the rest were either at the furthest end of the planet, or even worse, were off the mainland altogether. Subedei, however, was not perturbed by this revelation, pointing to how the first great rail project had shown the way.

There was a more pressing danger posed by the Dutch forces. While the Mongolian population rejoiced over the crushing victory against the Americans, the Dutch had advanced their strong rifle divisions into the mountains by New Koningsberg. The citizens of New Koningsberg were very aware that the bulk of the troops were still in the Ameruican lands, and so even with the power of infantry divisions protecting the city, there was a concern with the closeness of this Dutch presence.

However, Subedei had reserved the artillery. There had been no need for this weapon against the defenders that America had been able to field. However, Dutch rifle divisions hiding in the mountains were a different story, and artillery was rushed to the front to dispense with the imminent threat. With the numbers of these powerful bombardment tools that Subedei had at his disposal, the Dutch troops fell into disarray. It was then easy pickings for cavalry divisions to charge into the mountains and finish off the Dutch resistance. In all four divisions of rifles and one division of longbows were slaughtered.

This did not end the Dutch offensive, however, as tens of thousands of Dutch troops, mainly in rifle divisions, were on the march through the jungles of former Germany towards the Mongol city of Berlin.

As the year 1415AD was heralded in, Subedei was able to turn the considerable might of the Mongol military machine to directly face the Dutch, and the Mongol counter-offensive began. The Dutch had been using the city of Frankfurt as their staging point to launch their attacks against the Mongols, so it was only natural that this city become the first target for Subedei. Following a heave artillery barrage, Frankfurt was then charged by cavalry divisions. The stunned defenders were no match for these Mongolian divisions, and in the process of liberating Frankfurt, Jochi stepped forward as a new Mongolian military leader.

Then the Mongolian artillery was brought to bear upon the Dutch advance in the jungle. After another heavy bombardment, a mix of cavalry divisions and even infantry divisions were used on the attack to wipe out a full 130,000 Dutch invaders.

The Dutch response was starting to weaken. A smaller troop advanced on Frankfurt in an attempt to liberate this former Dutch city. In a further act of desperation, the Dutch signed a mutual protection pact with the one city state, Byzantines. a Pact that was really of no benefit to either civilisation. It did however result in the Mongols now facing a second foe, even if the danger from that quarter was almost non-existent.

In all this war excitement, the sages were met with a somewhat muted response to their demonstration of the secrets of Mass Production. However, their new research goal, motorised transport, and the ultimate tool that this was thought to deliver to the battlefield was warmly greeted. So once again the sages were granted the full funding necessary to pursue this latest task.

Then as 1420AD dawned, Subedei had access to his fully healed armies to strike the Dutch with. At Novosibirsk, the eight cavalry army dispensed with two rifle divisions, and Chagatai’s keshik army eliminated the third and final rifle division to prise this city from the Dutch.

In the south by the Great Dividing Range, the Dutch had previously formed a small colony called Delft. This year was to be its swansong as it was first hit by a cavalry army, and then finished off by the seventh cavalry army. Two rifle divisions were accounted for in the process.

By Frankfurt, the new Dutch advance is again shelled by the artillery, and then attacked by elite cavalry divisions, spawning another leader for the Mongols. The leader was quickly whisked home to Karakorum to establish another currently empty army.

It was fully 1425AD, before the last Dutch city in the west was within range of the Mongols. The now tried and tested method of artillery bombardment followed by cavalry charge quickly dislodged the two rifle divisions of defenders.

This action cleared the Dutch presence from the east altogether. However, now the Mongol military machine had to face up to the logistical nightmare that the western part of the Dutch empire represented. The Netherlands were isolated in the far north west of the continent, with the full breadth of Babylonia, and the Incan territory at its widest part separating the Mongols and Dutch nations. What’s more, neither the backward Babylonians, nor the Incans had an established rail net, so getting forces to the front, and then reinforcements afterwards was going to be a major problem.

The first great railing project had given the Mongols an idea. This time however, the distance was far greater. The second great railing project was commenced, joining up where the first had left off. In addition, because the railing effort was so reliant on the existing road network, a direct path for the rails could not be used. The railroad had to follow this winding road passage.

In any event, with the Khan’s full backing, many worker crews left the Mongolian core and started work on this most ambitious task. The first phase of the project extended right through Babylon and into Inca, and comprised fully 2800 kilometres of track. It also brought the Mongols right up to the new advanced guard of the Dutch comprising fully 180,000 soldiers!

These troops were caught unawares. With the speed of the rail system in place, Subedei was able to ferry his well rested armies directly to the front, and strike at these rifle divisions of the enemy. As the force was a mix of rifles and longbow divisions, the armies dispensed with the rifles and the cavalry cleaned up the longbows. In this way, the Mongols suffered minimum casualties, but this large force was decimated, staining the Tiwanaku forests a deep red.

In 1430AD the phase two of the track was completed. A further 1200 kilometres of track brought it to the mountains south of the Netherland city of Groningen. Three hundred kilometres extended west to the lone Dutch city of Eindhoven as well, and so the final assault on the Netherlands could begin.

The city of Groningen was struck first. After an extensive artillery barrage, cavalry moved in to clean up the rest. This time though, the Mongols were attacking the heart of the Dutch nation, and so the defence was that more resolute. In spite of the fierce artillery barrage, the defence remained determined, and claimed two full cavalry divisions. But the loss to the Dutch was far worse, as five divisions of rifles were crushed, and even Groningen fell.

Eindhoven was next. It took two cavalry armies and a cavalry division to smash through the four divisions of rifles and one longbow division guarding the city, and claim it for the Mongols.

Then the Mongols moved into the very heart of the Netherlands. The important harbour city of Maastricht was next. Maastricht was important because it provided access to the Dutch Island city of Holwerd, and unlike the Byzantine’s island city, this island was large enough to land an invasion force next to the city, and so it was not the invulnerable fortress that the Byzantine city currently represented. Maastricht, however, was over the hills, thus limiting the range of the attacking units. A small amount of artillery was yet unutilised, so a small preliminary bombardment preceded the action here as two keshik armies and one cavalry army mounted the rise and assaulted the city, destroying four rifle divisions in the process. Maastricht fell.

Another three hundred kilometres of railing brought the Mongols over to the west coast, and within reach of the city of Rotterdam. A cavalry army and a keshik army combined to kill the four rifle divisions in this city.

More railing brought Amsterdam within range, however, Subedei was once again running short on armies. He decided to utilise one of the spare armies in Karakorum now, instead of waiting for the super weapon of the future, and so filled the ninth cavalry army. Due to distance, Amsterdam required no less than five armies, but eventually fell, and with it the ancient wonders of the Great Lighthouse and the Colossus fell into Mongolian hands.

Subedei was ever keen to continue his offensive, and so he created the tenth cavalry army, and rushed it into action at Haarlem. Single handedly this new army destroyed three rifle divisions to capture the city.

This last push has reduced the Dutch to their three mainland cities and their island city. The Dutch also have twelve divisions in Incan territory near the Mongols’ new rail infrastructure. Chebe advised not to even bother with these units. The Dutch command structure would soon be in tatters and the threat from these units would them dissipate. So instead of launching any offensives against them, the infrastructure and worker crews are protected by strong infantry divisions and the Dutch are invited to do their worst.

1435AD is a quiet year on the military front. Numerous Mongolian units need a well earned rest and recovery time, and the final Mongolian cities are spread far from the borders. An advance is made on the remaining three, but only at The Hague, does battle commence. Due to the distance, it takes a full four cavalry armies to bridge the gap and attack, destroying the three rifle divisions, and capturing this one city.

However the year is memorable for another much more important region. The sages were to return once again to the Khan’s court with news of a new announcement. This time they were very warmly greeted, especially when they revealed the new toy to the generals. It met and far exceeded their expectations.

The celebrations were exuberant to say the least. When the partying was finally over, the sages were authorised to pursue amphibious warfare, again with generous funding. Meanwhile, all military builds across the entire huge Mongolian empire were swapped immediately to this new devastating tool. Furthermore, this new weapon inspired the Khan to reconsider his world view. It was clear that the world remained hostile towards the Mongols, and with each new foe being vanquished, the resentment of the remaining nations grew. It seemed inevitable that when the Dutch were shortly brought under control, the huge borders of the Mongols would be at risk from either the Babylonians or the Incans over what-ever slight infraction they deemed to have occurred. The only path to a peaceful future appeared to be after a short period of all out war.

This the Khan pondered at some length.

Sandman2003

Prince

It won't be domination. Conquest seems a more fitting way to end this. At the point we are up to in the story, we have 52% of area and 79% of population. If we stopped the military campaign now, and spent the next however long just cash rushing temples, we might be able to already trigger domination, but it would not be as satisfying.

Sandman2003

Prince

Well you know, real life gets in the way at times.

General Mayhem

Monarch

- Joined

- Aug 30, 2004

- Messages

- 329

Keep up the good work, I should go away for a few days more often, all my favorite stories have been updated

Alpha Infantry

Makin Ya Mans Clap You!

RRROOOFFFFLLLLMMMAAAOOOO!!!!!rbis4rbb said:Real life? Is that some new mod?

Anyway, nie story.

you kickin The Dutch's ass.

Sandman2003

Prince

Glad you guys are continuing ot enjoy the story, rbis4rbb, General Mayhem and Alpha Infantry. Now a new chapter!

Sandman2003

Prince

Chapter Twenty-One – Pax Mongolia

The Khan called all his heads of staff into an all important conference on the future of the Mongol State, and on the future of the world itself. The Khan stated that for the first time in the history of the planet, the Mongols now had the ability to permanently impose a peace upon the world, under the iron rule of the Mongols. Every time in the past, when the Mongol’s had achieved peace it had been fleeting, as another challenger rose to bring conflict to the Mongolian nation. With these new tanks, the Mongols could decisively gain the upper hand and end the future threat posed by these other ‘civilisations’.

The message was generally well received, after all the Mongols had a proud warrior tradition. It was certainly true that the periods of peace during the Mongols existence had been fleeting at best, and the prospect of a true ongoing peace was an honourable aim. However, there were those present at the meeting who questioned whether the mere demonstration of this powerful weapon could potentially bring the remaining civilisations into line?

They considered who was left. The Byzantines had had all the mainland territory stripped off them and existed in a cramped island off the coast ever bitter towards the Mongolians. No demonstration of power was going to end their leaders’ desire for revenge upon the Mongols.

Then there were the Dutch with three cities remaining. Right now they were locked in a life or death struggle with the Mongols. The fact that they were prepared to honour their American Pact even after seing the rapid fall of their ally, surely demonstrated the depths that these other nations would go to, to oppose the Mongols..

The Babylonians had a large territory, but remained quite backward. Their leaders continued the façade of a separate national identity at the expense of modernising the nation. Though they represented no immediate threat to the Mongols, there was no doubt that the Babylonian people would be better off under Mongolian rule, and that the leadership would be determined in their resistance to this goal.

The Inca were the largest and strongest of the remaining civilisations. It was clear that they had intentions to independently assert their own culture and greatness on the planet. This would inevitably result in a demand for more space, and sooner or later bring them into conflict with the Mongols, especially when there was no other civilisation.

Therefore, the more the politicians considered their options, the more attractive a policy of direct action became. Strike now while we have a significant technological advantage, and instil our ‘Pax Mongolia’ upon the world, insisted Chebe.

The Khan’s Military Council meets

In the end, the Khan’s wishes were agreed to unanimously. The military council set about drawing up the all important war plans. Right of Passage agreements existed with both the Babylonians and the Incans. With the intention to bring peace to the world through the superior might of Mongolian troops now firmly established, the effectiveness of the tactics used to eliminate the threat of the Byzantines were considered to be a suitable method for hastening the departure of the unnecessary regimes of the Babylonians and the Incans.

Clearly the Babylonians would make an easier first target while the production lines continued to roll off these new tank divisions for the greater assault on the Incans. There was no need to delay war preparations on the Babylonian front for the Dutch. Their three cities would not last long, and they could not cause any real harm to the Mongol forces arrayed against them. For this reason, healed divisions and newly created tank divisions were ordered to move immediately into targeting positions within the Babylonian lands.

Subedei passed off the remaining war against the Dutch to the veritable old general Chagatai, while he moved to supervise the positioning in the Babylonian lands. Chagatai launched simultaneous attacks on the two remaining Dutch mainland cities of Arnheim and Utrecht. At Arnheim the fighting remains fierce. The defenders show no sign of being an almost beaten nation, and even succeed in retreating a cavalry army! However, this simply is not enough, and the city falls.

At Utrecht, due to the substantial distance the armies had to cross into the foreign borders, it takes most of Chagatai’s army force to generate sufficient assaults, but of course the Dutch have no answers for this onslaught and fall to the invaders.

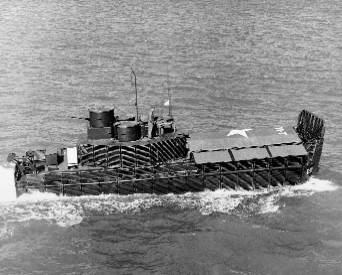

In the harbour city of Maastricht, the resitance has been fully overwhelmed. Takign advantage of this situation, Chagatai uses the local maritime skills to rush build a transport – the first for the Mongols – loads it with a cavalry army and sends it on its way to the final bastion of Dutch resistance, the island city of Holwerd.

Subedei sees no point in holding off the armies for filling with tanks. With two spare commanders waiting in Karakorum, they are both granted a commission and form the eleventh and twelfth cavalry armies. Subedei reports to Chebe that the troops are in position, and awaits the order to go!

As the year 1445AD rolls around, the Babylonian ambassador is requested to an audience in the Mongol’s palace in Karakorum. The poor guy leaves absolutely astonished and shocked hearing that the Mongols were declaring war upon the Babylonians. There had been no negotiation, just a blunt statement that the Babylonians would be better off under Mongol rule, rather than the corrupt Babylonian government, therefore Mongol forces had moved into position to eliminate this tyranny from the world, and as they spoke the order had been given to strike at targets within the ‘corrupt’ nation. Subedei was then given the green light for action!

As Chagatai reports the successful landing of the cavalry army on Holwerd island, Subedei passes on the order to attack to his troops. At the mountain hideaway of Izibia, there is an underestimation of the strength of the defence, as even four divisions are insufficient to claim the city, though as a consolation another leader is generated form the fierce battle.

At Larsa the story goes according to plan as a cavalry army kills three muskets to claim the city. At Akkad the story is the same, except that the 7th Keshik army is used to destroy the three musket divisions. Ashur puts up some resemblance of resistance holding off the initial three cavalry division assaul;t, but when reinforced with two armies and a fourth cavalry division, the resistance is overwhelmed and the city falls.

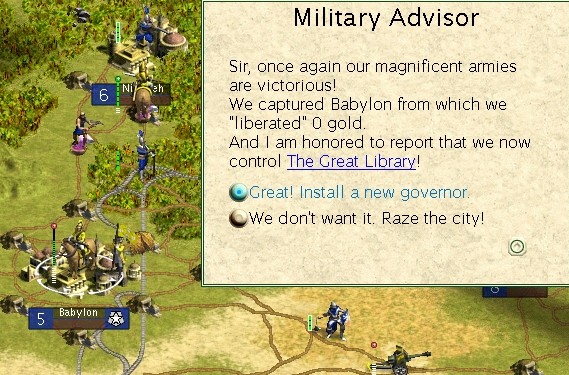

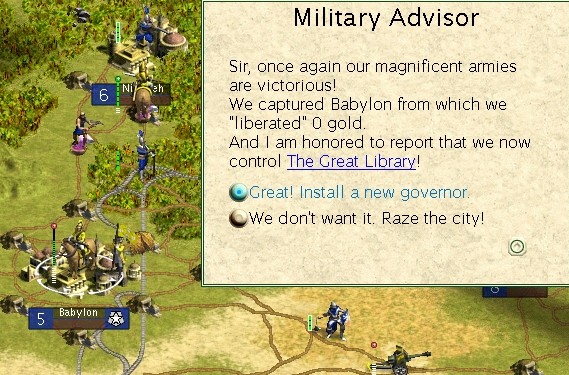

The capital city of Babylon is also hit in the first phase of the war. Kublai’s keshik army alone is sufficient to destroy three musket divisions and claim the Babylonian capital. The pride of the Babylonians falls with this city.

At Nippur the second keshik army kills the two musket divisions to claim the city. At Ninevah it is two cavalry divisions that smash the two musket divisions and claim the city. Elipi is struck by the recently formed eleventh cavalry division, and their training proves the equal of the more experienced units, resulting in the destruction of three musket divisions to liberate the city.

At Eridu, another cavalry army kills two musket divisions to claim the city. At Uruk it is a keshik army that kills two musket divisions to claim the city.

Finally the new tank divisions get to see some action. At Luernco Marque, two tank divisions are used to smash the two musket defending divisions and claim the city. At Adab, it takes only a single tank division to kill the standard two musket divisions and liberate the city. In all, eleven cities fell in this initial phase of the Babylonian war. With their technological weakness relative to the Mongols, it was not expected that the Babylonians would last long.

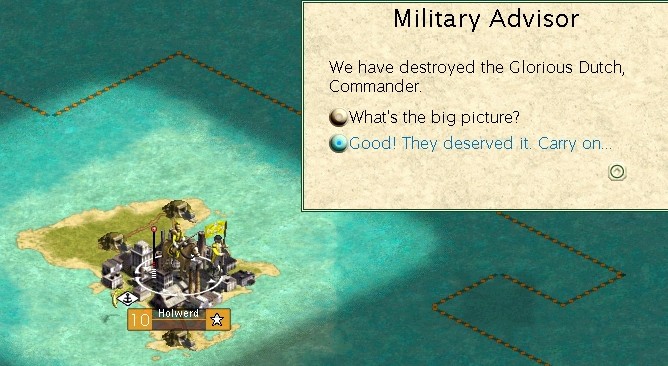

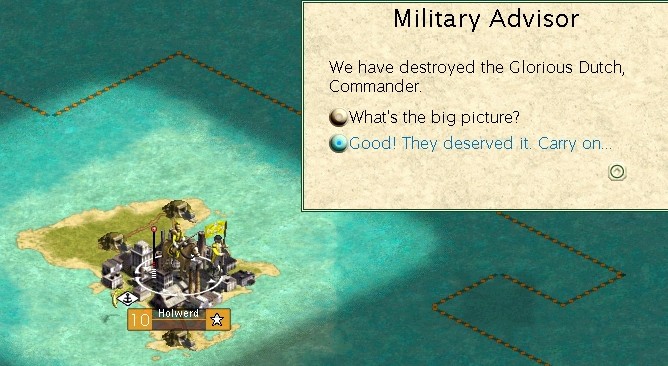

1450AD sees the Dutch conflict resume. Tolui’s cavalry army takes heavy fire from the last bastion of the old Dutch regime, but it is not enough to blunt the Mongolian resolve. Three rifle and a longbow division perish in the final assault. Chagatai breathed a sign of relief at the end, owing to the huge toll that Tolui’s army takes, but finally it is over. The Dutch entered the war in 1400AD, so exactly fifty years later they paid for their misplaced loyalty.

The Khan called all his heads of staff into an all important conference on the future of the Mongol State, and on the future of the world itself. The Khan stated that for the first time in the history of the planet, the Mongols now had the ability to permanently impose a peace upon the world, under the iron rule of the Mongols. Every time in the past, when the Mongol’s had achieved peace it had been fleeting, as another challenger rose to bring conflict to the Mongolian nation. With these new tanks, the Mongols could decisively gain the upper hand and end the future threat posed by these other ‘civilisations’.

The message was generally well received, after all the Mongols had a proud warrior tradition. It was certainly true that the periods of peace during the Mongols existence had been fleeting at best, and the prospect of a true ongoing peace was an honourable aim. However, there were those present at the meeting who questioned whether the mere demonstration of this powerful weapon could potentially bring the remaining civilisations into line?

They considered who was left. The Byzantines had had all the mainland territory stripped off them and existed in a cramped island off the coast ever bitter towards the Mongolians. No demonstration of power was going to end their leaders’ desire for revenge upon the Mongols.

Then there were the Dutch with three cities remaining. Right now they were locked in a life or death struggle with the Mongols. The fact that they were prepared to honour their American Pact even after seing the rapid fall of their ally, surely demonstrated the depths that these other nations would go to, to oppose the Mongols..

The Babylonians had a large territory, but remained quite backward. Their leaders continued the façade of a separate national identity at the expense of modernising the nation. Though they represented no immediate threat to the Mongols, there was no doubt that the Babylonian people would be better off under Mongolian rule, and that the leadership would be determined in their resistance to this goal.

The Inca were the largest and strongest of the remaining civilisations. It was clear that they had intentions to independently assert their own culture and greatness on the planet. This would inevitably result in a demand for more space, and sooner or later bring them into conflict with the Mongols, especially when there was no other civilisation.

Therefore, the more the politicians considered their options, the more attractive a policy of direct action became. Strike now while we have a significant technological advantage, and instil our ‘Pax Mongolia’ upon the world, insisted Chebe.

The Khan’s Military Council meets

In the end, the Khan’s wishes were agreed to unanimously. The military council set about drawing up the all important war plans. Right of Passage agreements existed with both the Babylonians and the Incans. With the intention to bring peace to the world through the superior might of Mongolian troops now firmly established, the effectiveness of the tactics used to eliminate the threat of the Byzantines were considered to be a suitable method for hastening the departure of the unnecessary regimes of the Babylonians and the Incans.

Clearly the Babylonians would make an easier first target while the production lines continued to roll off these new tank divisions for the greater assault on the Incans. There was no need to delay war preparations on the Babylonian front for the Dutch. Their three cities would not last long, and they could not cause any real harm to the Mongol forces arrayed against them. For this reason, healed divisions and newly created tank divisions were ordered to move immediately into targeting positions within the Babylonian lands.

Subedei passed off the remaining war against the Dutch to the veritable old general Chagatai, while he moved to supervise the positioning in the Babylonian lands. Chagatai launched simultaneous attacks on the two remaining Dutch mainland cities of Arnheim and Utrecht. At Arnheim the fighting remains fierce. The defenders show no sign of being an almost beaten nation, and even succeed in retreating a cavalry army! However, this simply is not enough, and the city falls.

At Utrecht, due to the substantial distance the armies had to cross into the foreign borders, it takes most of Chagatai’s army force to generate sufficient assaults, but of course the Dutch have no answers for this onslaught and fall to the invaders.

In the harbour city of Maastricht, the resitance has been fully overwhelmed. Takign advantage of this situation, Chagatai uses the local maritime skills to rush build a transport – the first for the Mongols – loads it with a cavalry army and sends it on its way to the final bastion of Dutch resistance, the island city of Holwerd.

Subedei sees no point in holding off the armies for filling with tanks. With two spare commanders waiting in Karakorum, they are both granted a commission and form the eleventh and twelfth cavalry armies. Subedei reports to Chebe that the troops are in position, and awaits the order to go!

As the year 1445AD rolls around, the Babylonian ambassador is requested to an audience in the Mongol’s palace in Karakorum. The poor guy leaves absolutely astonished and shocked hearing that the Mongols were declaring war upon the Babylonians. There had been no negotiation, just a blunt statement that the Babylonians would be better off under Mongol rule, rather than the corrupt Babylonian government, therefore Mongol forces had moved into position to eliminate this tyranny from the world, and as they spoke the order had been given to strike at targets within the ‘corrupt’ nation. Subedei was then given the green light for action!

As Chagatai reports the successful landing of the cavalry army on Holwerd island, Subedei passes on the order to attack to his troops. At the mountain hideaway of Izibia, there is an underestimation of the strength of the defence, as even four divisions are insufficient to claim the city, though as a consolation another leader is generated form the fierce battle.

At Larsa the story goes according to plan as a cavalry army kills three muskets to claim the city. At Akkad the story is the same, except that the 7th Keshik army is used to destroy the three musket divisions. Ashur puts up some resemblance of resistance holding off the initial three cavalry division assaul;t, but when reinforced with two armies and a fourth cavalry division, the resistance is overwhelmed and the city falls.

The capital city of Babylon is also hit in the first phase of the war. Kublai’s keshik army alone is sufficient to destroy three musket divisions and claim the Babylonian capital. The pride of the Babylonians falls with this city.

At Nippur the second keshik army kills the two musket divisions to claim the city. At Ninevah it is two cavalry divisions that smash the two musket divisions and claim the city. Elipi is struck by the recently formed eleventh cavalry division, and their training proves the equal of the more experienced units, resulting in the destruction of three musket divisions to liberate the city.

At Eridu, another cavalry army kills two musket divisions to claim the city. At Uruk it is a keshik army that kills two musket divisions to claim the city.

Finally the new tank divisions get to see some action. At Luernco Marque, two tank divisions are used to smash the two musket defending divisions and claim the city. At Adab, it takes only a single tank division to kill the standard two musket divisions and liberate the city. In all, eleven cities fell in this initial phase of the Babylonian war. With their technological weakness relative to the Mongols, it was not expected that the Babylonians would last long.

1450AD sees the Dutch conflict resume. Tolui’s cavalry army takes heavy fire from the last bastion of the old Dutch regime, but it is not enough to blunt the Mongolian resolve. Three rifle and a longbow division perish in the final assault. Chagatai breathed a sign of relief at the end, owing to the huge toll that Tolui’s army takes, but finally it is over. The Dutch entered the war in 1400AD, so exactly fifty years later they paid for their misplaced loyalty.

Sandman2003

Prince

Chapter Twenty One continued

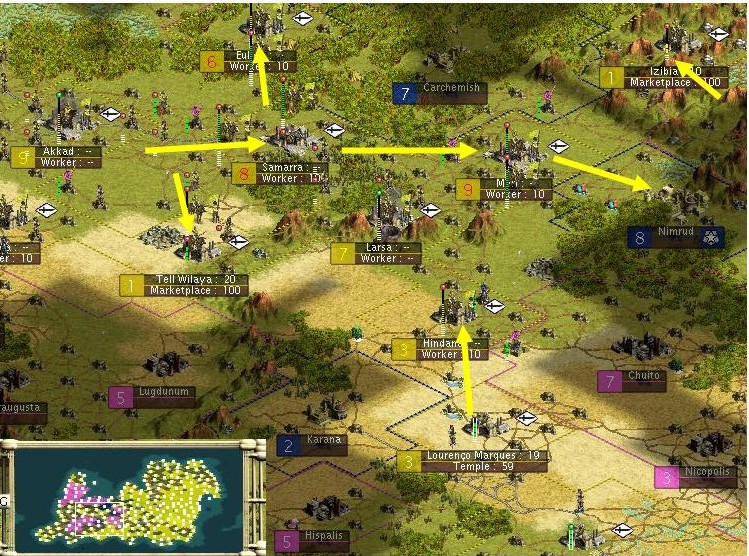

The much depleted Babylonians are then hit with the second phase of Subedei’s campaign. The mountain retreat of Izibia is unable to hold out a second time and the remaining musket division falls to the cavalry division assault. Then Sippar falls to the third keshik army, Zamua falls to another cavalry army, and although taking two cavalry armies to finish the job Samarra also falls to the Mongols. Seven more musket divisions perished in these brutally efficient assaults.

The defenders at Tel Wilyara put up a more determined effort, even though their poorly equipped divisions consist of only one musket division, one pike division and a medieval infantry division. In the end, the combined force of a keshik army and two csvalry divisions prove sufficient to crush this attempt to hold onto power.

At Eulbar, a cavalry army and a keshik army combine to destroy three musket divisions and take the city. Evora too commits sheer numbers of troops in a brave, determined, but ultimately futile attempt to resist the Mongolian might. Tanks are used in numbers here to crush the defence. However, it is not quite the walk-over that was expected. Babylonian troops die in their thousands, but through their sheer numbers drag the battle out over several nights of intense fighting. The awesome power of the tank at night is a sight to behold, and in the numbers eventually used by the Mongols it is just far too overwhelming for even the most determined musket defence.

The city of Mari is taken more easily by two keshik armies. Then Hindana falls to a single cavalry army. In the last military act of 1450AD, the city of Nimrod falls to a cavalry army – keshik army combo. The resulting battle debis leaves behind the bodies of two musket divisions, a pike division and a medieval infantry division.

The resulting advance over just five years completely shattered the previous empire of Babylon, and left them with but three isolated cities. Of course, the Mongols had no intention of stopping here. Once started, the war was driven to its inevitable conclusion.

In 1455AD, the remaining battle honours were shared between the tank divisions and the keshik armies as the final two Babylonian cities were assaulted and defeated. Three musket divisions and three pike divisions were the last resistance put up buy the Babylonians, before the end. Finally, they were no more!

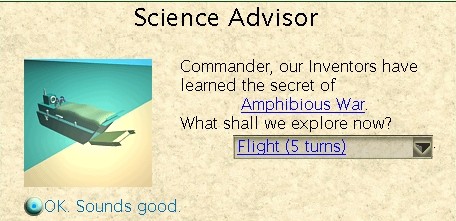

The news of the Babylonian decline was greeted with much cheer in Karakorum, but the good news did not stop there. The sages presented a new technology to the court, that of amphibious warfare.

For the first time in the Mongols history they now possessed a means to end the irritation of the east. As a few cities were directed to manufacture these new marine units, preparations were underway to plan the assault of the Incans, the last great remaining civilisation!

The much depleted Babylonians are then hit with the second phase of Subedei’s campaign. The mountain retreat of Izibia is unable to hold out a second time and the remaining musket division falls to the cavalry division assault. Then Sippar falls to the third keshik army, Zamua falls to another cavalry army, and although taking two cavalry armies to finish the job Samarra also falls to the Mongols. Seven more musket divisions perished in these brutally efficient assaults.

The defenders at Tel Wilyara put up a more determined effort, even though their poorly equipped divisions consist of only one musket division, one pike division and a medieval infantry division. In the end, the combined force of a keshik army and two csvalry divisions prove sufficient to crush this attempt to hold onto power.

At Eulbar, a cavalry army and a keshik army combine to destroy three musket divisions and take the city. Evora too commits sheer numbers of troops in a brave, determined, but ultimately futile attempt to resist the Mongolian might. Tanks are used in numbers here to crush the defence. However, it is not quite the walk-over that was expected. Babylonian troops die in their thousands, but through their sheer numbers drag the battle out over several nights of intense fighting. The awesome power of the tank at night is a sight to behold, and in the numbers eventually used by the Mongols it is just far too overwhelming for even the most determined musket defence.

The city of Mari is taken more easily by two keshik armies. Then Hindana falls to a single cavalry army. In the last military act of 1450AD, the city of Nimrod falls to a cavalry army – keshik army combo. The resulting battle debis leaves behind the bodies of two musket divisions, a pike division and a medieval infantry division.

The resulting advance over just five years completely shattered the previous empire of Babylon, and left them with but three isolated cities. Of course, the Mongols had no intention of stopping here. Once started, the war was driven to its inevitable conclusion.

In 1455AD, the remaining battle honours were shared between the tank divisions and the keshik armies as the final two Babylonian cities were assaulted and defeated. Three musket divisions and three pike divisions were the last resistance put up buy the Babylonians, before the end. Finally, they were no more!

The news of the Babylonian decline was greeted with much cheer in Karakorum, but the good news did not stop there. The sages presented a new technology to the court, that of amphibious warfare.

For the first time in the Mongols history they now possessed a means to end the irritation of the east. As a few cities were directed to manufacture these new marine units, preparations were underway to plan the assault of the Incans, the last great remaining civilisation!

mevlin

Chieftain

Nice one Sandman! You inspired me to go and win my first Monarch Pangea map thanks to this. Never was able to win a Pangea before!

Sandman2003

Prince

Congrats on your pangea win, mevlin.

Tman65

Warlord

Stories like this help to add a whole new dimension to game play, not to mention being highly entertaining!

Go, go, go

Go, go, go

Sandman2003

Prince

Thanks Tman65, glad you enjoyed it. rbis4rbb, I haven't actually achieved conquest yet. There is at least one more chapter to go.

Similar threads

- Sticky

- Replies

- 30

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 808

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 233

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 2K