It's true that there was a process of Anglicisation after the Union of Crowns and particularly Act of Union that deepened the distinctions between Highlands and Lowlands, but I don't think it's right to say that this represented a process of de-Gaelicisation, or at least not more than inadvertently so. The Gaels had been marginalised since the 14th century, when the Anglo-Norman nobility lead by the Stewarts gained dominance, and at that point such changes would have filtered down to the commoners only gradually. (The only ones who would likely pay much attention were the town-dwellers, and they were already the most Anglicised part of the population because of the trade links with England.) Whatever Gaelic culture it stripped from the Lowlands would have been somewhat residual, and probably unrecognised.

If there was a real change between 1300 and 1800, it's the emergence of the concept of nationhood itself, which meant that the previous understanding of Scotland as an essentially political entity, and thus one which could accommodate multiple peoples, gave way to an understanding of Scotland as a cultural entity, which meant that the dominant group had to exclude the marginal groups from defining this culture. Robert Bruce could rule Gaels and Inglismen and call them both "Scots", but George III apparently found himself less able.

So what I meant was that Gaelic in Scotland was perceived until the 18th century as being the ancestral language of all Scot, even those not speaking it (and even those in the Merse, where it was never dominant), and people had a variety of accounts why the language "changed" (Malcolm married Margaret, the treason of the earls of Dunbar, Edward I introducing it). But that idea was systematically assaulted in the 18th and 19th centuries by Teutonist antiquarians, as you probably know.

But an interesting point to make, and one that I frequently make to colleagues, is that the Celtic term Alba actually represents a diachronic semantic continuum that stretches back even to the era before the Romans: "Britain", "non-Roman Britain", "Pictland-Scotland". That's not necessarily a "nation" in the modern sense, but nonetheless is related (and just read your early Irish sagas if you want to see whether or not the concept is important!). Also, like I also like to point out, many European nations are actually derived from established church provinces, derived often from Roman administrative provinces , from which the modern ideas are derived. Examples exclude "Spain", "Germany", "Italy", "Russia" (medieval), and indeed "Scotland" (medieval).

Well, again, I think what we're seeing here isn't so much fragmentation as a heightened

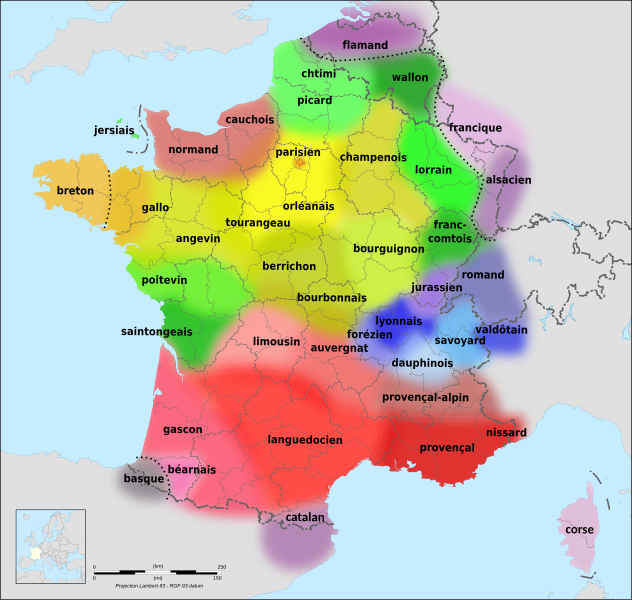

awareness of fragmentation. A good example of this is found in the organisation of the Knights Hospitaller, which divided itself into a number of "Tongues"- sub-orders based on place of origin. The French knights could be place in the Tongues of France, Auvergne or Provence, which shows an awareness that these regions had different native languages (note the limited use of "France"!), but at the same time the Tongue of Germany also include Hungary, Poland, Bohemia and Scandinavia, showing that they were only held linguistic categories to be of so much significance. (Also, it's interesting to note that Aragon had it's own Tongue, while Portugal was lumped in with Castille. Another example of the essential arbitrariness of modern "nations"!

)

Yes, modern nations are arbitrary in this sense. The vast majority are inventions of the 19th and 20th century, and their use as modes of historical narrative is my bete noir.

The latin word "Lingua" is ambiguous, like most words. Think of semantic hierarchies, concentric semantic circles. Here language is at the centre, but related meanings like race, and region are on the outer parts. The extension of such a region is not so linguistically arbitrary as you may think. The burgher and much of the upper classes of Poland, Hungary and Bohemia were German in speech (the lingua franca of eastern Europe until the age of Stalin) in the later middle ages, and Scandinavians were often seen as Germans (one 13th century Icelandic source apparently says Icelanders could understand the language as far south as Mainz!). For "Latin Europe", the Latins (Frenchies. Italians, Iberians) formed a core group, and often all other western Europeans were treated as "Germans" when administratively convenient (for instance, in earlier universities).

And, btw, yes, I remember reading an account of Vasco da Gama's voyage and they were refering to their language as Castilian ... probably meaning they perceived their dialect of Romance as somehow a version of the Romance associated with the Castilian court. Aragonese has been oscured by the patriotism and hegemonic role of Catalan, though incidentally the early medieval kingdom of Aragon was actually Basque (though many modern Spanish history enthusiasts will deny this, that's what the evidence strongly suggests).

Edit: Also, it's probably good luck that this thread turned up this week, and not next week, by which time I'll have gotten my grubby mits on a copy of

Vanished Kingdoms by Norman Davies, and would likely find myself completely unable to shut the hell up about exactly how made up "nations" actually are. So consider yourself lucky!

Yes, saw that. I'm always interested to hear what people say, so long as it's sensible.

)

) )

)

(Although I'll note that the point about the role of German as a lingua franca in much of Central Europe is a good one. I suppose I'm committing the very crime that I'm supposedly railing in against in supposing that "Poland .'. they speak Polish"!

(Although I'll note that the point about the role of German as a lingua franca in much of Central Europe is a good one. I suppose I'm committing the very crime that I'm supposedly railing in against in supposing that "Poland .'. they speak Polish"!  )

) ) , but doen't serve well to that proverbial diversity.

) , but doen't serve well to that proverbial diversity.