The book I quoted says that

Roman cataphracts were meant mostly to fight against infantry, not that this applied to all cataphracts throughout history (remember that cataphracts existed for 1800 years). The Romans had a distinction for cataphracts and clibanarii, the latter being mostly against cavalry. In Non-Roman armies units called clibanarii didn't exist, so their anti-cavalry role was also played by cataphracts.

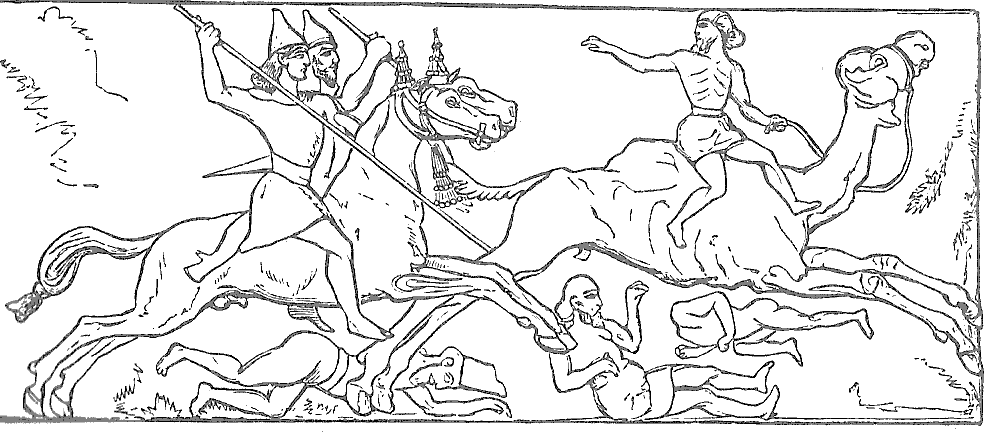

As for the Parthians, the Seleucids and the Achaemenids - neither of them were the first ones recorded by sources to use cataphracts. That goes to the Scythians and the Massagetae, in 530 BC, when cataphracts under Tomyris defeated the Persian army and killed Cyrus II. Achaemenids adopted cataphracts from their steppe enemies but 1) it is unclear when and 2) they never had them in significant numbers, unlike later the Parthians, the Seleucids and the Sassanids. At Gaugamela Alexander's Hetairoi did not face them.

The first confirmed by sources appearance of cataphracts in the Roman army was in 130 AD, but they started to be used in large numbers after the 210s AD. Roman encounters with cataphracts were not only in the East (Parthian, Seleucid, Palmyrene, Mithridatic, Sassanid, etc. cataphracts) but also along the Danube, where they fought against the Roxolani in 60 - 68 AD and then in the Dacian wars. Maybe such Roxolani foreigners recruited to the Roman army following the 117 AD treaty between Emperor Hadrian and King of the Roxolani Rasparaganus were the first cataphracts of Rome, while later they started to recruit citizens of the Empire as cataphracts. In the Middle Ages cataphracts continued to be used by Eastern Romans.

The last time Byzantine cataphracts were used on a large scale was in the 13th century.

So the 13th century ended the 1800 years long military history of cataphracts.

BTW - cataphracts were also used in China, but I don't know whether the Chinese developed them independently or adopted them from the western direction. Or the other way around.

noblemen called to join a temporary campaign rather than full-time professional soldiers

Being a nobleman and a full-time professional soldier aren't mutually exclusive things. Just like today being from a middle class family and a profesional soldier is also not impossible. Roman cataphracts were full-time professional, paid soldiers. But I don't think that they were recruited mostly from peasants.

at Immae and Emesa, the Palmyrene cataphracts exhausted themselves by running around chasing the Romans too much and were defeated.

In the Roman account of the battle of Emesa I haven't seen anything indicating that it was exhaustion which caused the defeat of cataphracts. The account is actually rather clear, that it was the loss of cohesiveness and the dispersal of their formation (they were chasing the Romans and dispersed themselves in the process, instead of keeping their formation intact), followed by a sudden Roman counterattack.

As for Immae I haven't read about that battle yet, but I will check this too.

Another reason cataphracts were probably expected to prioritize fighting cavalry is their origin. They seem to have originated with eastern peoples like the Sakae, Sarmatians, and various other Iranic peoples who fought mainly as cavalry against other cavalry.

Indeed, but on the other hand the first recorded use of cataphracts was in 530 BC against the Persian army of Cyrus II, and that army was mostly infantry (like all Persian armies in that early period).

Bear in mind that the armored horsemen usually agreed to be cataphracts (it's not a terribly consistently applied term) weren't always strictly lancers, as many of them carried bows

Roman cataphracts = strictly lancers. Sagittari clibanarii were Roman armoured horse archers.