Sandman2003

Prince

Chapter Seven continued

440AD was a red letter year for the forces of Subedei. The assault on Delhi destroyed three more Indian spear battalions and an archer battalion to take the town, and saw the rising of yet another field commander to a position of glory, Chagati. Chagati was immediately sent to Bombay, commissioned to form a second Keshik army. But Subedei was not done there. The horse herds of Hyderabad, from which the Indians were making their horse battalions, were within easy reach. The prospect of being able to liberate the sacred animals from the yoke of Indian oppression drove Subedei onwards. Two Keshik battalions were enough to destroy the two Indian spear battalions and free both the town of Hyderabad and the herd of horses as well. And just for good measure, an Indian horse battalion being rushed to Delhi to support the garrison there was cut down by another Keshik battalion.

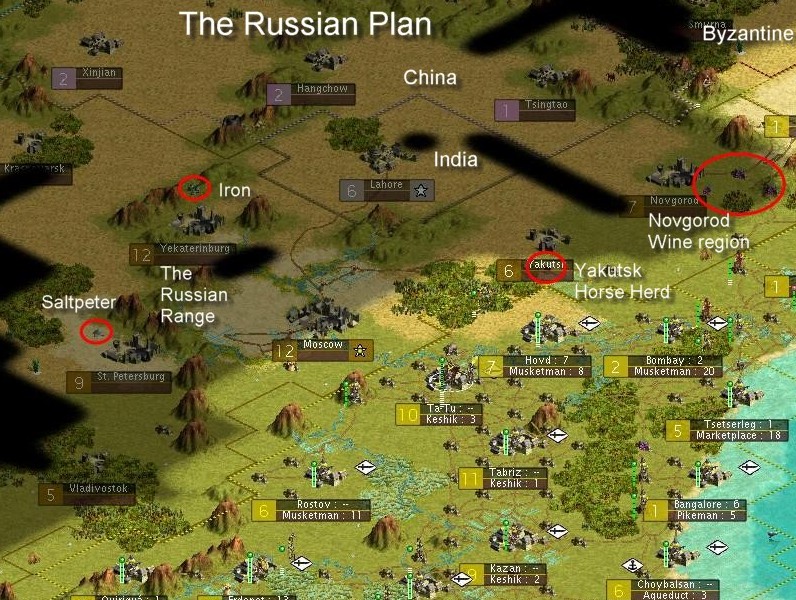

Ghandi himself managed to escape from the defeat at Delhi and establish a temporary governing residence at Jaipur. However, he realised that the unstoppable march of Subedei’s forces would soon attack here as well, and so a more permanent solution was sought at the town of Lahore, hidden as it was behind the territory of the Russians, and thus providing a defensive buffer from the Mongol attack.

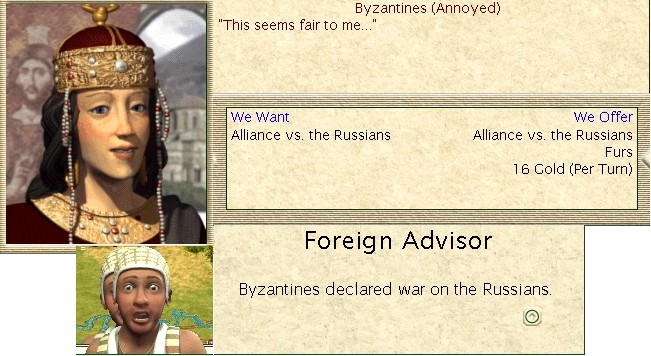

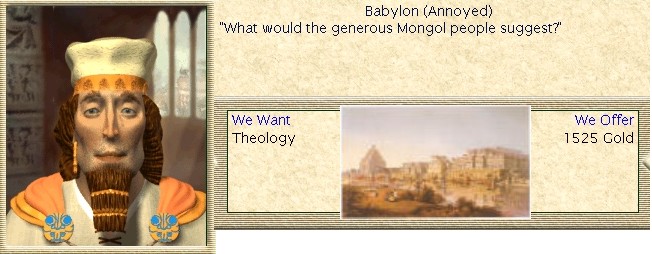

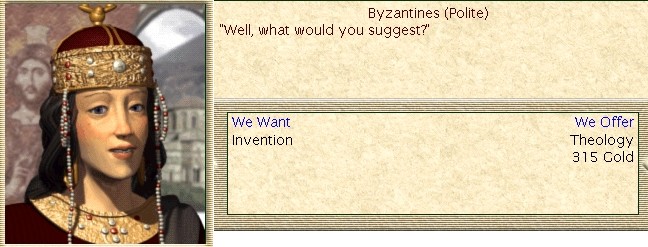

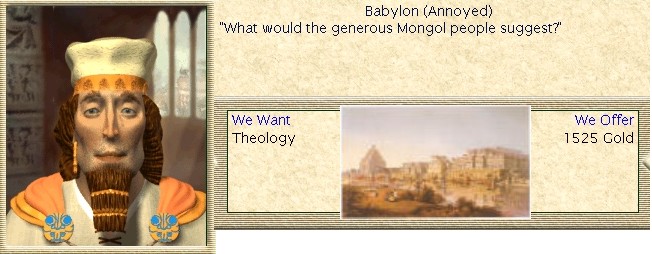

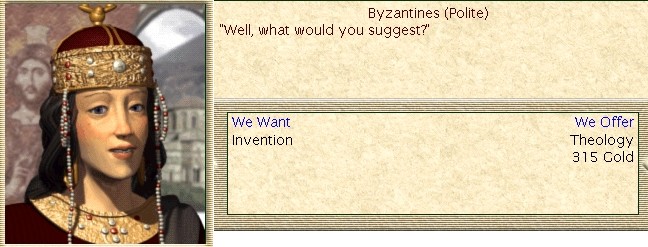

Back in Karakorum, Yeh-lu had returned from the international circuit with the knowledge that there existed an opportunity to bring the Mongols up to technological parity with the world’s leaders. It turned out the Byzantines did not yet possess the religious concept of theology and may be willing to trade such knowledge for the ability of invention. Invention was available from half a dozen sources globally, and so it was that a trade was organised once again with King Hammurabi of the Babylonian people.

The 1525 gold demanded by Hammurabi meant that there was insufficient gold left in the Treasury to satisfy Theodora on a swap for invention, however. And so it was not for a further decade that the Mongols had sufficient gold to make the Byzantine deal. Long gone was the previous antagonism between the Byzantines and the Mongols, and a very polite Theodora greeted Yeh-lu and affirmed the friendship between the two peoples.

Subedei’s campaign rolled on as the unstoppable war machine it was. But now it faced a new problem, and one which was not really caused by Ghandi at all. Subedei would have liked to split his forces and finish off the Indians within a couple of remaining decades, but this was not to be. The central area of the great Indian peninsular was riddled with extensive marshland known as the Jaipur Marshes. To the south of the Jaipur Marshes was dense jungle, called the Calcutta jungle, and to the north was a large range of mountains called the Karachi Mountains. Even for the lightly equipped Keshik, progress through the marshland or the jungle would be unacceptably slow, thus forcing Subedei’s forces to go around and over the Karachi Mountains. To make matters even worse, the Indian engineers had not even completed a pass through the mountains, and so when this journey was commenced, Subedei would be forever thankful of the design decisions taken by Yeh-lu that resulted in a light configuration for the Keshik, as this enabled rapid progress through the rugged terrain.

The Indian command structure was clearly broken, for although there were still many Indian units deployed against Subedei’s forces, they now appeared to lack cohesion and had little coordination in their attacks. And they continued to have no answer to the power of the Keshik! During the march to Jaipur, three more Indian horse battalions fell, though two of these emerged from a trek through the Calcutta Jungle to try and regain the Hyderabad horse herd. All were cut down easily and yet another battle field leader so distinguished himself as to also be commissioned to form an army. The leader Tolur was honoured to command the third Keshik army.

Subedei’s crushing victory at the town of Jaipur, in which a further three spear battalions were slaughtered, was in a way a mixed blessing for Subedei. General Ereen adopted his most diplomatic of stances to finally convince the Khan’s most trusted Military Advisor, General Chebe, that clearly Subedei had sufficient force to finish the Indians, and that the priority now lay with bringing the vile Greeks in line. The evidence overwhelmingly supported this view, and so Subedei was informed that while he could keep the forces currently under his command, that all new reinforcements would be directed to the Greek theatre of war, in expectation of the battles there. Subedei could see no point in arguing with this logic, for although he was to have no part in the Greek campaign, it was certainly true that the Indians were not going to survive his assaults much longer.

In the west, an Indian spear battalion was found lurking in the forests by Copan. The attack command was given to the local Keshik battalion, but perhaps lacking the inspirational leadership of Subedei in person, the Keshik unit found itself repulsed by the spear unit, and then showing weakness in retreat, the Indian spear was able to take advantage of the situation and cut down the battalion. This small victory was one of the few things giving the Indians some vain hope. But it was not to last, the spear battalion was soon destroyed by another Keshik.

General Ereen now had gathered a full division of mounted troops, and so began his advance on the Greek town of Thermoplae. The forward division was backed with a further two keshik and one pike battalions. Ereens troops were not to have the advantage of surprise, however, as they found themselves ambushed by a Greek archer battalion, and owing to the accuracy of the Greek archers in their opening salvos, they were able to dispatch a full battalion of the advancing keshiks, before succumbing to the inevitable counterattack.

Ereen’s advance finally brought him to the gates of Thermoplae itself, and the Keshik battalions were to prove almost as decisive under Ereen’s command as they had under Subedei. Although the fanatical hoplite had more battle mettle than the Indian soldiers had possessed, even with the help of an archer battalion, those hoplites were at best able to turn the first Keshik charge at Thermoplae, before succumbing to the superior equipment, and superior numbers of Ereens troops. 3000 Greek soldiers perished in the battle that saw Ereen capture Thermoplae. But in one last act of defiance, the residents of Thermoplae destroyed the galley that was in port, rather than let it fall into Mongolian hands.

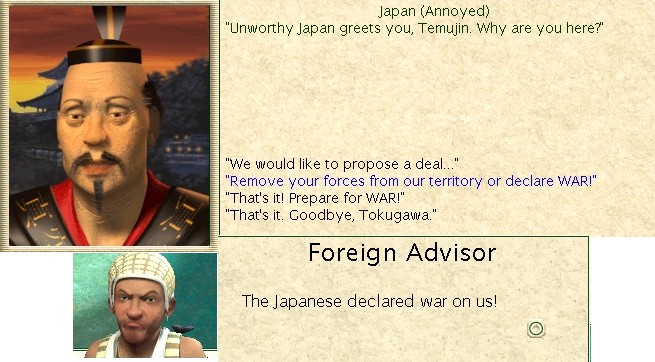

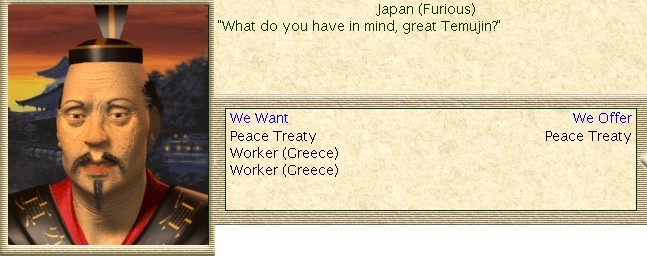

It was at this time that the military alliance with the Japanese against the Greeks was due to expire, and so Shogun Tokugawa himself journeyed to Karakorum to request the continuance of the alliance against the mutually hated foe. This time the Khan had no hesitation in continuing this alliance, for regardless of whatever small value his Japanese ally provided, this time the Khan was prepared to see the campaign run through to fruitition, such was his anger still at the atrocity of Ulaangrom. It was also at this time that Yeh-lu brought news that the mighty German people had completed a training facility, called Knights Templar, for an elite foot soldier troupe, rumoured to be considerably stronger than the Mongols’ own medieval infantry. The troupe lacked the mobility of the Mongol Keshik, however, and so was not considered to be a significant threat at the time.

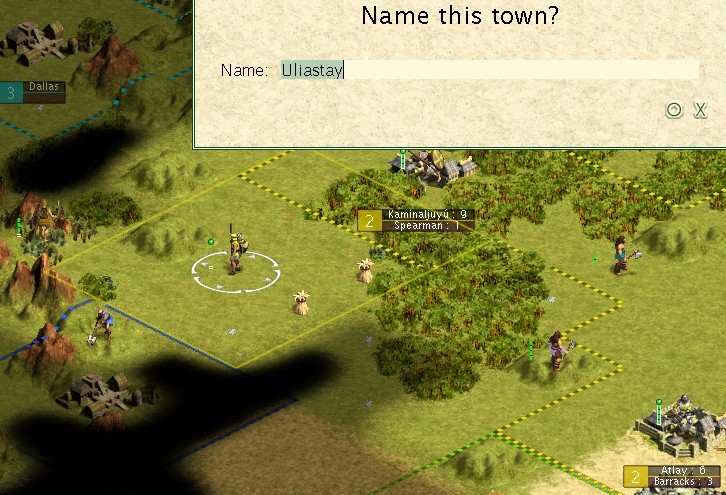

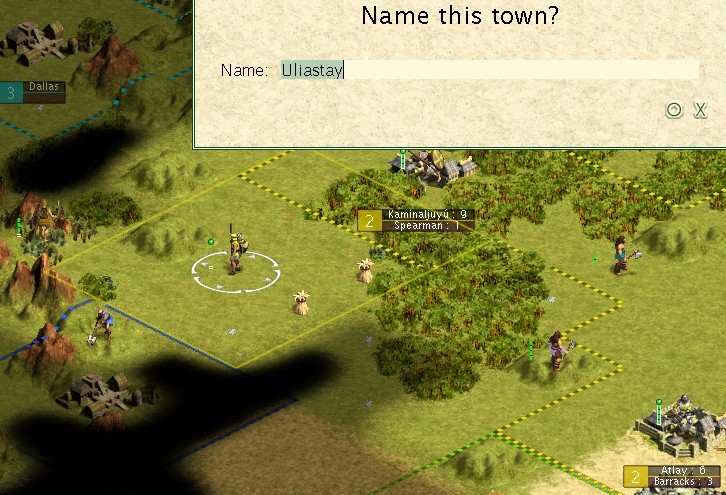

Meanwhile, the Mongols’ continual population growth and demand for more space, resulted in the settling of a new town, Uliastay by the town of Kaminaljuro in the rich grasslands to the west. Uliastay was right up next to the border with the Mayan’s new second town, perhaps acting as a reminder to the Khan that there was unfinished business there as well.

Meanwhile, Subedei was not to be outdone by his rival general, and so on hearing of the capture of Thermoplae, he immediately ordered the assaults on both Madras and Karachi. The town of Madras was an important hub, situated as it was between the great powers of the Byzantines to the east, the Chinese to the north, and the Russians to the west. But that didn’t make its defence any sturdier, as the first Keshik Army mowed through two Indian spear battalions to seize the city.

The defenders at Karachi were taken by complete surprise by the speed of the Keshik advance, foolishly believing that the difficult mountain terrain would give them time to prepare for the attack. They were wrong, and three Keshik battalions accounted for the spear battalions defending here as well.

And in an attempt to make it three, Subedei ordered two elite sword battalions to attack the Indian city of Chittingong in the far west. This city was one of two Indian cities forming the New Indian Territories. But the three-peat was not to be, as the Indian spear battalions held firm. The battle was evenly divided with about 1000 casualties on each side.

But the Indians were not done with their atrocities even yet. A horse battalion, with orders direct from Lahore and Ghandi himself, used the veil of secrecy provided by Russian territory to attack another party of defenceless workers by Hovd, and butcher more Mongolian lives.

Ereen was pushing on as well. The town of Mycenae was next. Though it cost another Keshik battalion, two more Greek hoplite battalions were destroyed resulting in the capture of the town.

The Mongolian military might was continuing to grow, and had just reached the strength of three full divisions of Keshiks, 30 battalions. Subedei continued to put the forces at his disposal to good use, using the second and third keshik armies to smash resistance in Calcutta, and then making the long trek to Kolhapur.

Realising that Kolhapur represented the last town of the old Indian core, and that the Khan was unlikely to authorise committing troops to hunting down and destroying the remaining and widely spread towns of India, Subedei decided to end the Indian campaign with a bang. First an elite horse battalion was sent in to Chittagong with orders to raze the city to the ground, after dispensing with an archer battalion en route. Then and only then did the assault on Kolhapur commence. A further two spear and one archer battalions fell as Kolhapur came under Mongol power.

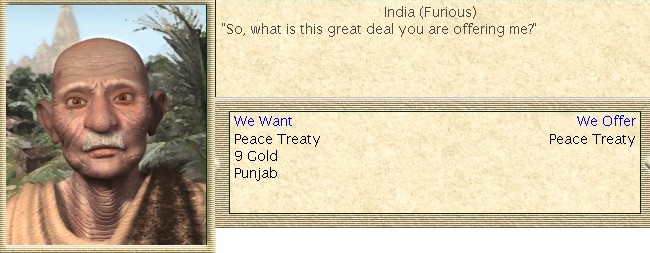

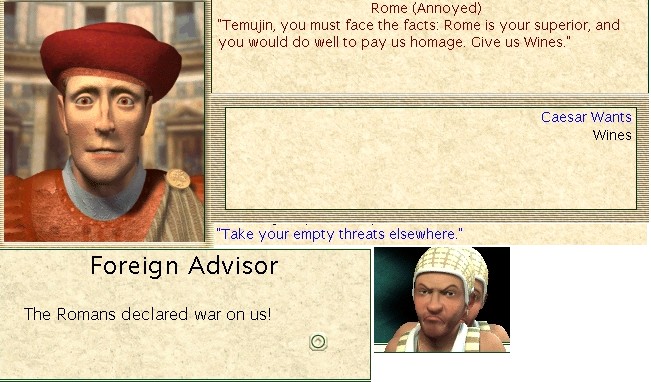

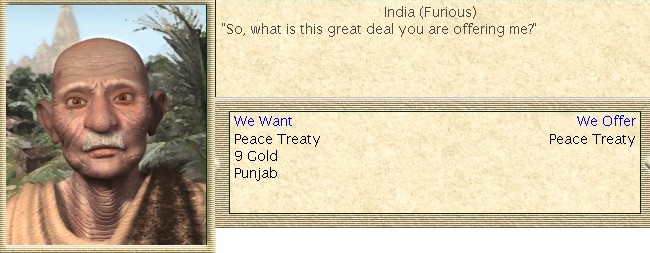

Subedei’s concerns were realised, as the Khan, himself, intervened at this point. The Khan was aware of the locations of only two of the remaining three Indian cities, and so as a ploy to extract the location of the third, the town was demanded in the peace settlement. It turned out that Punjab was founded in the midst of the Great Dividing Range itself, next to a gem source, but also perilously close to the expanding Roman empire.

440AD was a red letter year for the forces of Subedei. The assault on Delhi destroyed three more Indian spear battalions and an archer battalion to take the town, and saw the rising of yet another field commander to a position of glory, Chagati. Chagati was immediately sent to Bombay, commissioned to form a second Keshik army. But Subedei was not done there. The horse herds of Hyderabad, from which the Indians were making their horse battalions, were within easy reach. The prospect of being able to liberate the sacred animals from the yoke of Indian oppression drove Subedei onwards. Two Keshik battalions were enough to destroy the two Indian spear battalions and free both the town of Hyderabad and the herd of horses as well. And just for good measure, an Indian horse battalion being rushed to Delhi to support the garrison there was cut down by another Keshik battalion.

Ghandi himself managed to escape from the defeat at Delhi and establish a temporary governing residence at Jaipur. However, he realised that the unstoppable march of Subedei’s forces would soon attack here as well, and so a more permanent solution was sought at the town of Lahore, hidden as it was behind the territory of the Russians, and thus providing a defensive buffer from the Mongol attack.

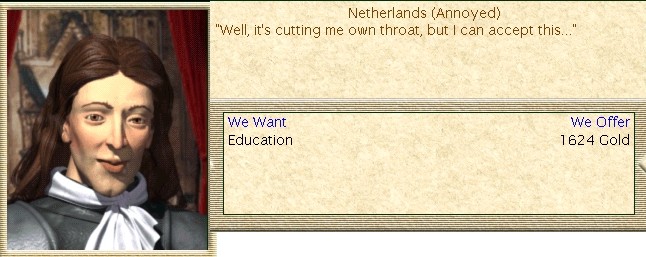

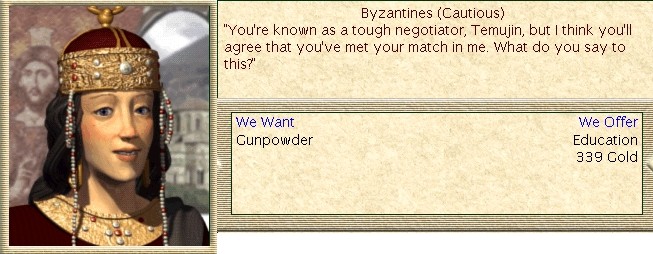

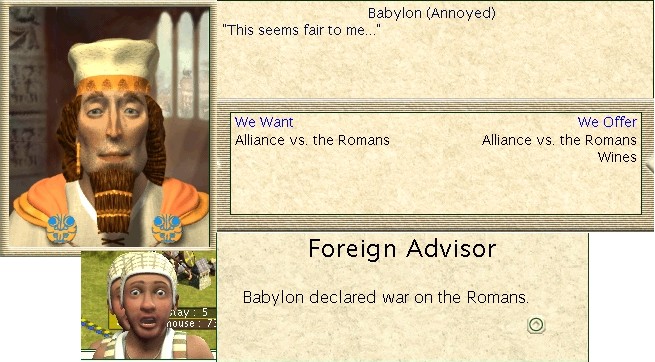

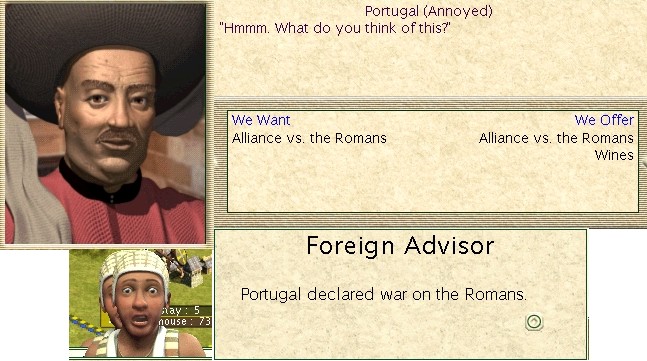

Back in Karakorum, Yeh-lu had returned from the international circuit with the knowledge that there existed an opportunity to bring the Mongols up to technological parity with the world’s leaders. It turned out the Byzantines did not yet possess the religious concept of theology and may be willing to trade such knowledge for the ability of invention. Invention was available from half a dozen sources globally, and so it was that a trade was organised once again with King Hammurabi of the Babylonian people.

The 1525 gold demanded by Hammurabi meant that there was insufficient gold left in the Treasury to satisfy Theodora on a swap for invention, however. And so it was not for a further decade that the Mongols had sufficient gold to make the Byzantine deal. Long gone was the previous antagonism between the Byzantines and the Mongols, and a very polite Theodora greeted Yeh-lu and affirmed the friendship between the two peoples.

Subedei’s campaign rolled on as the unstoppable war machine it was. But now it faced a new problem, and one which was not really caused by Ghandi at all. Subedei would have liked to split his forces and finish off the Indians within a couple of remaining decades, but this was not to be. The central area of the great Indian peninsular was riddled with extensive marshland known as the Jaipur Marshes. To the south of the Jaipur Marshes was dense jungle, called the Calcutta jungle, and to the north was a large range of mountains called the Karachi Mountains. Even for the lightly equipped Keshik, progress through the marshland or the jungle would be unacceptably slow, thus forcing Subedei’s forces to go around and over the Karachi Mountains. To make matters even worse, the Indian engineers had not even completed a pass through the mountains, and so when this journey was commenced, Subedei would be forever thankful of the design decisions taken by Yeh-lu that resulted in a light configuration for the Keshik, as this enabled rapid progress through the rugged terrain.

The Indian command structure was clearly broken, for although there were still many Indian units deployed against Subedei’s forces, they now appeared to lack cohesion and had little coordination in their attacks. And they continued to have no answer to the power of the Keshik! During the march to Jaipur, three more Indian horse battalions fell, though two of these emerged from a trek through the Calcutta Jungle to try and regain the Hyderabad horse herd. All were cut down easily and yet another battle field leader so distinguished himself as to also be commissioned to form an army. The leader Tolur was honoured to command the third Keshik army.

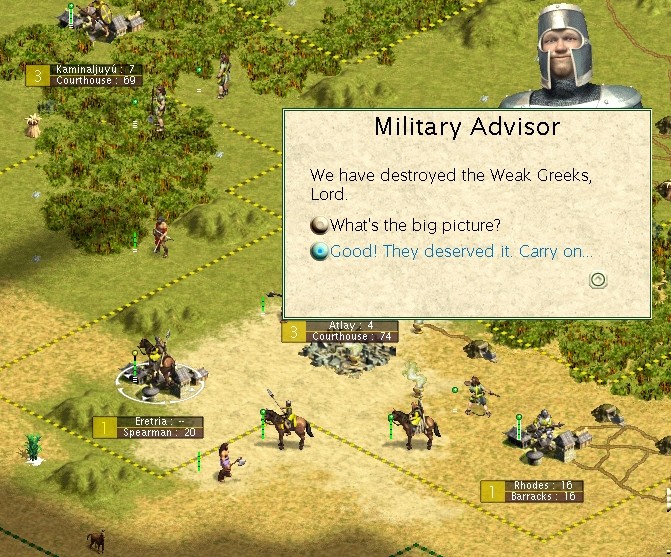

Subedei’s crushing victory at the town of Jaipur, in which a further three spear battalions were slaughtered, was in a way a mixed blessing for Subedei. General Ereen adopted his most diplomatic of stances to finally convince the Khan’s most trusted Military Advisor, General Chebe, that clearly Subedei had sufficient force to finish the Indians, and that the priority now lay with bringing the vile Greeks in line. The evidence overwhelmingly supported this view, and so Subedei was informed that while he could keep the forces currently under his command, that all new reinforcements would be directed to the Greek theatre of war, in expectation of the battles there. Subedei could see no point in arguing with this logic, for although he was to have no part in the Greek campaign, it was certainly true that the Indians were not going to survive his assaults much longer.

In the west, an Indian spear battalion was found lurking in the forests by Copan. The attack command was given to the local Keshik battalion, but perhaps lacking the inspirational leadership of Subedei in person, the Keshik unit found itself repulsed by the spear unit, and then showing weakness in retreat, the Indian spear was able to take advantage of the situation and cut down the battalion. This small victory was one of the few things giving the Indians some vain hope. But it was not to last, the spear battalion was soon destroyed by another Keshik.

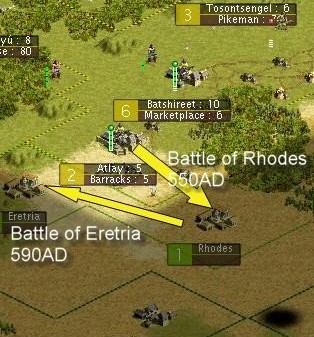

General Ereen now had gathered a full division of mounted troops, and so began his advance on the Greek town of Thermoplae. The forward division was backed with a further two keshik and one pike battalions. Ereens troops were not to have the advantage of surprise, however, as they found themselves ambushed by a Greek archer battalion, and owing to the accuracy of the Greek archers in their opening salvos, they were able to dispatch a full battalion of the advancing keshiks, before succumbing to the inevitable counterattack.

Ereen’s advance finally brought him to the gates of Thermoplae itself, and the Keshik battalions were to prove almost as decisive under Ereen’s command as they had under Subedei. Although the fanatical hoplite had more battle mettle than the Indian soldiers had possessed, even with the help of an archer battalion, those hoplites were at best able to turn the first Keshik charge at Thermoplae, before succumbing to the superior equipment, and superior numbers of Ereens troops. 3000 Greek soldiers perished in the battle that saw Ereen capture Thermoplae. But in one last act of defiance, the residents of Thermoplae destroyed the galley that was in port, rather than let it fall into Mongolian hands.

It was at this time that the military alliance with the Japanese against the Greeks was due to expire, and so Shogun Tokugawa himself journeyed to Karakorum to request the continuance of the alliance against the mutually hated foe. This time the Khan had no hesitation in continuing this alliance, for regardless of whatever small value his Japanese ally provided, this time the Khan was prepared to see the campaign run through to fruitition, such was his anger still at the atrocity of Ulaangrom. It was also at this time that Yeh-lu brought news that the mighty German people had completed a training facility, called Knights Templar, for an elite foot soldier troupe, rumoured to be considerably stronger than the Mongols’ own medieval infantry. The troupe lacked the mobility of the Mongol Keshik, however, and so was not considered to be a significant threat at the time.

Meanwhile, the Mongols’ continual population growth and demand for more space, resulted in the settling of a new town, Uliastay by the town of Kaminaljuro in the rich grasslands to the west. Uliastay was right up next to the border with the Mayan’s new second town, perhaps acting as a reminder to the Khan that there was unfinished business there as well.

Meanwhile, Subedei was not to be outdone by his rival general, and so on hearing of the capture of Thermoplae, he immediately ordered the assaults on both Madras and Karachi. The town of Madras was an important hub, situated as it was between the great powers of the Byzantines to the east, the Chinese to the north, and the Russians to the west. But that didn’t make its defence any sturdier, as the first Keshik Army mowed through two Indian spear battalions to seize the city.

The defenders at Karachi were taken by complete surprise by the speed of the Keshik advance, foolishly believing that the difficult mountain terrain would give them time to prepare for the attack. They were wrong, and three Keshik battalions accounted for the spear battalions defending here as well.

And in an attempt to make it three, Subedei ordered two elite sword battalions to attack the Indian city of Chittingong in the far west. This city was one of two Indian cities forming the New Indian Territories. But the three-peat was not to be, as the Indian spear battalions held firm. The battle was evenly divided with about 1000 casualties on each side.

But the Indians were not done with their atrocities even yet. A horse battalion, with orders direct from Lahore and Ghandi himself, used the veil of secrecy provided by Russian territory to attack another party of defenceless workers by Hovd, and butcher more Mongolian lives.

Ereen was pushing on as well. The town of Mycenae was next. Though it cost another Keshik battalion, two more Greek hoplite battalions were destroyed resulting in the capture of the town.

The Mongolian military might was continuing to grow, and had just reached the strength of three full divisions of Keshiks, 30 battalions. Subedei continued to put the forces at his disposal to good use, using the second and third keshik armies to smash resistance in Calcutta, and then making the long trek to Kolhapur.

Realising that Kolhapur represented the last town of the old Indian core, and that the Khan was unlikely to authorise committing troops to hunting down and destroying the remaining and widely spread towns of India, Subedei decided to end the Indian campaign with a bang. First an elite horse battalion was sent in to Chittagong with orders to raze the city to the ground, after dispensing with an archer battalion en route. Then and only then did the assault on Kolhapur commence. A further two spear and one archer battalions fell as Kolhapur came under Mongol power.

Subedei’s concerns were realised, as the Khan, himself, intervened at this point. The Khan was aware of the locations of only two of the remaining three Indian cities, and so as a ploy to extract the location of the third, the town was demanded in the peace settlement. It turned out that Punjab was founded in the midst of the Great Dividing Range itself, next to a gem source, but also perilously close to the expanding Roman empire.