You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Timeline Building Experiment, v1.0

- Thread starter Daftpanzer

- Start date

Ninja Dude

Sorry, I wasn't listening...

Aww, no great war on democracy? I was quite looking forward to that...

Don't worry. Good ol' communism should be on its way soon. Then every one will have a common enemy!

qoou

Emperor

- Joined

- Dec 13, 2007

- Messages

- 1,991

Which is another reason why I was looking forward to some democrat-killing: none of my empires have fallen apart yet, and it's time that one of them burned, fell over, and sank into a swamp (except there'd be no one to build another empire) (Monty Python reference).

Dannydehz

Chieftain

- Joined

- Mar 25, 2007

- Messages

- 94

Hello,

I'm interested in joining, but being the NES newbie that I am, I have a question regarding the cultures I can choose from.

Each culture has major and lesser influence in one or more different states. How does that work exactly? I've read that multiple players can hold influence in a single state, so I guess that having a major influence in state A, while one (or more) players with lesser influence in the same state will make it more likely that your orders are followed?

I'm interested in joining, but being the NES newbie that I am, I have a question regarding the cultures I can choose from.

Each culture has major and lesser influence in one or more different states. How does that work exactly? I've read that multiple players can hold influence in a single state, so I guess that having a major influence in state A, while one (or more) players with lesser influence in the same state will make it more likely that your orders are followed?

Terrance888

Discord Reigns

A Major Influence means that a large part of that is under your culture, so a larger part of your orders will be followed and a compromise will usually be toward your orders.

A Lesser Influence means that you can effect it but it will be minor and very easily overshadowed by the ordrs of a Major Influence.

But still, lesser influence is enough to enforce changes large enough to help your overall culture.

A Lesser Influence means that you can effect it but it will be minor and very easily overshadowed by the ordrs of a Major Influence.

But still, lesser influence is enough to enforce changes large enough to help your overall culture.

Daftpanzer

canonically ambiguous

Spoiler short version :

Technology of the leading powers is roughly at World War One levels (greater and lesser in some areas).

Big wars happened in Europe and North America, but nothing like a real 'world war' yet.

There is a possibility of deadly disease spreading from India.

Big wars happened in Europe and North America, but nothing like a real 'world war' yet.

There is a possibility of deadly disease spreading from India.

Long version: (couldn't help getting carried away

)

)Era 16: Imperialism and Ideology

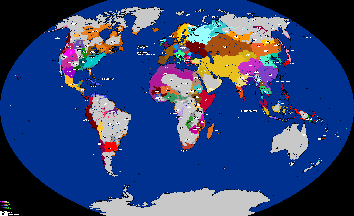

Map 1875:

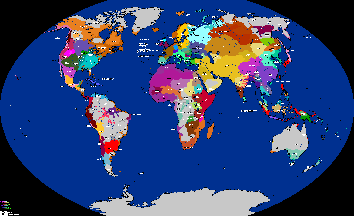

Map 1910:

THE NEW WORLD:

Spoiler :

NORTH AMERICA:

The Aarut expand their influence over the peoples of the far north-west. The Great Washagon Federation eventually spreads as far as the [Alaskan] coast, where it competes against the Suraji and Waeluta 'invaders' from far-east Asia.

Aarut explorers reach the mysterious Lanataw Kingdom, an old offshoot of the Xanto civilization. Although originally 'heretics' from the Lantan faith, they have preserved much of the old Xanto culture due to their isolation. Writings of these travels are published in the Old World and renew foreign interest in Xanto-Lantan culture.

After getting their hands on modern rifles, the Huomei horse-riding peoples are able to forge powerful states in the northern plains. For a while they are happy to attack other native states (and each other), but later turn hostile to the expanding Aarut colonies.

In alliance with the Suraji foreigners, the Hachago Kingdom expands to become a new empire on the western coast. It later competes with the Xanto Empire for influence over the Xante states, heartland of Xanto culture.

The Emperor of Antehauta inherits the Xanauk kingdom [central Texas] after a marriage between ruling families. But the core territories of the two states are separated by the isolationist Namache tribes - a war is fought to consolidate the new greater empire, now known as the Empire of the Xanto (although the leaders of Hachago could equally claim that title). The new empire also makes another attempt to annex the Marinata kingdoms [California], forcing them to seek the protection of the Suraji [north Japanese] colonists. The southern Lantamac Empire is then drawn into the fighting against the Xanto

Although only a sideshow compared to events elsewhere, this war still claims tens of thousands of lives. With their enemies being equipped with Suarji weapons (including early machine-guns), the Xanto are outgunned and forced to back down on some of their claims. The Xanto Empire does however become a closer ally of the Panto, and the fighting in the west ends in time for them to send expeditions to the [Mississippi] to aid in the fight against Aarut invasions. This is made easier by the building of great roadways between east and west.

New forges and cannon foundries are also built, with some use of steam power. The Xanto Empire becomes the leader of native industrial efforts, in terms of both quantity and quality. Although foreign technology is slowly being absorbed, the Xanto benefit more from an influx of Panto armourers and metalworkers fleeing westwards from the Aarut armies. The motivation is almost entirely militaristic. Industry for commerce and profit remains a foreign idea.

Marinata becomes a joint protectorate of the Suraji and northern Hachago. Lantamac gains more ground, but grows wary of growing Suraji power.

Hopes of some kind of peace accord between the Aarut and Panto come to nothing. Bitter fighting continues for decades, varying between small skirmishes and all-out war. The Aarut deploy tens of thousands of new troops to the continent, with machine-guns and heavy artillery, backed up by the big guns of their warships. At times they take control of around half the combined Panto territories. The fighting spreads to the Dahukat lands [Great Lakes] and other territories across the north-east. Airships are brought in to terrify the natives.

Panto industry is small-scale and chaotic compared to the Aarut. But they are able to arm themselves with basic explosive-shot cannons, mortars, and gunpowder-rocket launchers. Panto rifles are simple but effective, and very reliable. Arms dealers and smugglers from other European states (even some unscrupulous ones from Aarut) are also happy to deal with the Panto, if and when they can sneak through the Aarut blockade.

There are many frustrating sieges and counter-sieges on the Atlantic coast. Trench lines appear, similar to those seen in Europe. The Panto build crude-but-effective anti-ship mines in large numbers, and these prove to be a pain for the Aarut, sinking several ships, including one of their newest, largest all-metal warships. The Panto also build the first submarines, primitive human-powered tubs, but these have no real success.

Gains and losses are made by both sides. The Aarut look for a breakthrough further south.

In 1888, the Aarut 'surge' along the [Mississippi] makes rapid progress. The Panto leadership comes close to the point of collapse. But this coincides with the outbreak of war in Europe, while there is growing trouble in the [Brazilian] colonies and elsewhere. Aarut troops are gradually called away to other fronts.

Some Panto tribes take the opportunity to switch sides, or settle old scores. But most of them rally around the common cause of defending their homeland. Grievances between different tribes and ethnic groups are largely forgotten, at least for now. Other native peoples under attack (or threat of attack) by the Aarut begin to ally with the Panto.

Under pressure to achieve decisive victory, some Aarut commanders use brutal tactics (equal to the Rosk in Amestria). Panto cities are burned to the ground, and there are massacres of women and children, although few reports make it back to European newspapers. The Panto fight back just as viciously, and make the most of their home terrain. Despite all the new weapons employed, the fighting is sometimes hand-to-hand. Holding land proves more costly than taking it. Panto casualties number in the hundreds of thousands, but the Aarut lack the strength to launch the anticipated knock-out blow.

Things begin to quiet down around 1900. The Aarut gain the [Great Lakes] and other parts of the north, but are forced to 'temporarily' give up other holdings on the Atlantic coast and on the [Mississippi]. The Panto political system emerges much stronger than before, although it is more militarized, its manpower is depleted, and it is now reliant on the Xanto Empire for arms and supplies.

But, the fighting never truly stops. Frontier forces carry on the fight using terror tactics. Both sides bombard and sabotage each other at every opportunity.

Aarut soldiers look forward to the next 'big war' to finally stamp out the Panto Confederacy. But resentment grows among many Aarut colonists. In most cases the endless war is bad for trade and enterprise. The Aarut leadership is accused of persuing war for imperial glory, at the expense of allowing the colonies to prosper in peace.

CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA:

The Suraji conquer large swathes of territory from the Tumec and gain a foothold on the [Gulf of Mexico]. The Suraji also carve out a stronghold far to the south in [Peru], and also begin to explore and colonise the remote islands of the south Pacific.

Hulat territories expand deeper into northern South America, and then become united under a single ruler. Known as the Rayulat Kingdom, this southern Hulat state begins to separate from the old [Carribean] centres of power, and courts the attention of foreign powers (including Tezan and Kronahar, as well as the omnipresent Aarut).

Aarut begins a policy of taking direct control of the joint Argine-Aarut colonies in northern [Brazil]. This causes unrest among the colonists and chaos in the local government. Another rebellion occurs, which once again has to be crushed with brute force. The fighting spills across the border into the Zamarac Kingdom which is already home to many disaffected colonists. Aarut eventually succeeds in taking full control of the coast, but the area becomes less profitable, especially as a larger garrison is now needed to maintain order.

New colonies are set up by Tezan and Kronahar on the coast of [eastern Brazil]. The Kronahar colonists in particular push aggressively inland, despite the efforts of the Aarut privateers to strangle all trade competition in the Atlantic.

The power and influence of the Matac kingdom grows as it gains new territory along the Pacific coast, and makes contact with Suraji and Aarut foreigners. The kingdom prospers as a trade link between the Pacific and the interior of the [Amazon], especially as the neighbouring Colmassa kingdoms grow increasingly hostile to all foreign ideas and shut their doors to any trade with the Old World.

The Zanac kingdom emerges in the far south, spawned from the remains of recent Tezanian colonial efforts. The kingdom is founded by Great King Zuyca Hiyo, alleged to be the son of the famous Tezanian [north African] explorer Zhyrenigos and a native princess. There are some other foreign influences, including some Aarut and Suraji settlement (although the common people remain basically identical to the Colmassans further north).

The Aarut expand their influence over the peoples of the far north-west. The Great Washagon Federation eventually spreads as far as the [Alaskan] coast, where it competes against the Suraji and Waeluta 'invaders' from far-east Asia.

Aarut explorers reach the mysterious Lanataw Kingdom, an old offshoot of the Xanto civilization. Although originally 'heretics' from the Lantan faith, they have preserved much of the old Xanto culture due to their isolation. Writings of these travels are published in the Old World and renew foreign interest in Xanto-Lantan culture.

After getting their hands on modern rifles, the Huomei horse-riding peoples are able to forge powerful states in the northern plains. For a while they are happy to attack other native states (and each other), but later turn hostile to the expanding Aarut colonies.

In alliance with the Suraji foreigners, the Hachago Kingdom expands to become a new empire on the western coast. It later competes with the Xanto Empire for influence over the Xante states, heartland of Xanto culture.

The Emperor of Antehauta inherits the Xanauk kingdom [central Texas] after a marriage between ruling families. But the core territories of the two states are separated by the isolationist Namache tribes - a war is fought to consolidate the new greater empire, now known as the Empire of the Xanto (although the leaders of Hachago could equally claim that title). The new empire also makes another attempt to annex the Marinata kingdoms [California], forcing them to seek the protection of the Suraji [north Japanese] colonists. The southern Lantamac Empire is then drawn into the fighting against the Xanto

Although only a sideshow compared to events elsewhere, this war still claims tens of thousands of lives. With their enemies being equipped with Suarji weapons (including early machine-guns), the Xanto are outgunned and forced to back down on some of their claims. The Xanto Empire does however become a closer ally of the Panto, and the fighting in the west ends in time for them to send expeditions to the [Mississippi] to aid in the fight against Aarut invasions. This is made easier by the building of great roadways between east and west.

New forges and cannon foundries are also built, with some use of steam power. The Xanto Empire becomes the leader of native industrial efforts, in terms of both quantity and quality. Although foreign technology is slowly being absorbed, the Xanto benefit more from an influx of Panto armourers and metalworkers fleeing westwards from the Aarut armies. The motivation is almost entirely militaristic. Industry for commerce and profit remains a foreign idea.

Marinata becomes a joint protectorate of the Suraji and northern Hachago. Lantamac gains more ground, but grows wary of growing Suraji power.

Hopes of some kind of peace accord between the Aarut and Panto come to nothing. Bitter fighting continues for decades, varying between small skirmishes and all-out war. The Aarut deploy tens of thousands of new troops to the continent, with machine-guns and heavy artillery, backed up by the big guns of their warships. At times they take control of around half the combined Panto territories. The fighting spreads to the Dahukat lands [Great Lakes] and other territories across the north-east. Airships are brought in to terrify the natives.

Panto industry is small-scale and chaotic compared to the Aarut. But they are able to arm themselves with basic explosive-shot cannons, mortars, and gunpowder-rocket launchers. Panto rifles are simple but effective, and very reliable. Arms dealers and smugglers from other European states (even some unscrupulous ones from Aarut) are also happy to deal with the Panto, if and when they can sneak through the Aarut blockade.

There are many frustrating sieges and counter-sieges on the Atlantic coast. Trench lines appear, similar to those seen in Europe. The Panto build crude-but-effective anti-ship mines in large numbers, and these prove to be a pain for the Aarut, sinking several ships, including one of their newest, largest all-metal warships. The Panto also build the first submarines, primitive human-powered tubs, but these have no real success.

Gains and losses are made by both sides. The Aarut look for a breakthrough further south.

In 1888, the Aarut 'surge' along the [Mississippi] makes rapid progress. The Panto leadership comes close to the point of collapse. But this coincides with the outbreak of war in Europe, while there is growing trouble in the [Brazilian] colonies and elsewhere. Aarut troops are gradually called away to other fronts.

Some Panto tribes take the opportunity to switch sides, or settle old scores. But most of them rally around the common cause of defending their homeland. Grievances between different tribes and ethnic groups are largely forgotten, at least for now. Other native peoples under attack (or threat of attack) by the Aarut begin to ally with the Panto.

Under pressure to achieve decisive victory, some Aarut commanders use brutal tactics (equal to the Rosk in Amestria). Panto cities are burned to the ground, and there are massacres of women and children, although few reports make it back to European newspapers. The Panto fight back just as viciously, and make the most of their home terrain. Despite all the new weapons employed, the fighting is sometimes hand-to-hand. Holding land proves more costly than taking it. Panto casualties number in the hundreds of thousands, but the Aarut lack the strength to launch the anticipated knock-out blow.

Things begin to quiet down around 1900. The Aarut gain the [Great Lakes] and other parts of the north, but are forced to 'temporarily' give up other holdings on the Atlantic coast and on the [Mississippi]. The Panto political system emerges much stronger than before, although it is more militarized, its manpower is depleted, and it is now reliant on the Xanto Empire for arms and supplies.

But, the fighting never truly stops. Frontier forces carry on the fight using terror tactics. Both sides bombard and sabotage each other at every opportunity.

Aarut soldiers look forward to the next 'big war' to finally stamp out the Panto Confederacy. But resentment grows among many Aarut colonists. In most cases the endless war is bad for trade and enterprise. The Aarut leadership is accused of persuing war for imperial glory, at the expense of allowing the colonies to prosper in peace.

CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA:

The Suraji conquer large swathes of territory from the Tumec and gain a foothold on the [Gulf of Mexico]. The Suraji also carve out a stronghold far to the south in [Peru], and also begin to explore and colonise the remote islands of the south Pacific.

Hulat territories expand deeper into northern South America, and then become united under a single ruler. Known as the Rayulat Kingdom, this southern Hulat state begins to separate from the old [Carribean] centres of power, and courts the attention of foreign powers (including Tezan and Kronahar, as well as the omnipresent Aarut).

Aarut begins a policy of taking direct control of the joint Argine-Aarut colonies in northern [Brazil]. This causes unrest among the colonists and chaos in the local government. Another rebellion occurs, which once again has to be crushed with brute force. The fighting spills across the border into the Zamarac Kingdom which is already home to many disaffected colonists. Aarut eventually succeeds in taking full control of the coast, but the area becomes less profitable, especially as a larger garrison is now needed to maintain order.

New colonies are set up by Tezan and Kronahar on the coast of [eastern Brazil]. The Kronahar colonists in particular push aggressively inland, despite the efforts of the Aarut privateers to strangle all trade competition in the Atlantic.

The power and influence of the Matac kingdom grows as it gains new territory along the Pacific coast, and makes contact with Suraji and Aarut foreigners. The kingdom prospers as a trade link between the Pacific and the interior of the [Amazon], especially as the neighbouring Colmassa kingdoms grow increasingly hostile to all foreign ideas and shut their doors to any trade with the Old World.

The Zanac kingdom emerges in the far south, spawned from the remains of recent Tezanian colonial efforts. The kingdom is founded by Great King Zuyca Hiyo, alleged to be the son of the famous Tezanian [north African] explorer Zhyrenigos and a native princess. There are some other foreign influences, including some Aarut and Suraji settlement (although the common people remain basically identical to the Colmassans further north).

THE OLD WORLD:

Spoiler EUROPE :

EUROPE:

There are many discussions about uniting the Furotoca of Curias with the Orimudan Alliance. Many are not quite ready to accept such a change. Decades pass without a decision being made, although the two states become close allies. The northern powers of Aarut and Rosk become increasingly hostile towards them as their influence grows.

The Furotocans and their allies give full support to liberalist and democratic uprisings in eastern Europe, namely the Keyzad of Nadzavosk-Savizia and the Varakan Empire, leading to large-scale conflict from 1880 onwards. Furotocan ironclads and torpedo-boats defeat the Varakan [Mediterranean] fleet, which is left with only its few modern armoured cruisers to raid enemy supply lines (the building of a great canal between the Mediterranean and the [Red Sea] is still just an idea at this point, so the Varakans cannot deploy their mighty Indian Ocean fleet). Varakan forces are overstretched across their empire - despite the use of heavy artillery, machine-guns, and large airships for terror-bombing, they are ultimately unable to keep a hold on all their western territories.

Some uprisings are crushed, but after decades of fighting, several more liberalist states appear on the map - all of them are allied to the Furotocans and Orimudans, but few of them are very stable. Some refugees move into the Varakan Empire or Poneb, while others move to the Orimuda and Furotoca. Varakan knowledge of microbiology and the telegraph finds its way into Europe. The [Balkan] kingdoms of Varas and Arad (the 'Eastern Kingdoms') are the only ones to stubbornly resist the liberalists, and they form a small island of authoritarian rule.

But the spread of 'corrosive' liberalist ideas to the rest of Europe is basically an invention by Roskian and Aarut propagandists. The peasants of the Argine Empire remain apathetic, and the militarist-nationalism of the Amestrian Empire counters Furotocan influence in the north. Ironically, it is not until the Rosk Empire wages a brutal war on the Amestrians, supposedly to halt the spread of liberalist ideals, that those ideals actually gain more support across the rest of Europe.

The armies of Rosk invade the Amestrian Empire in 1885, and years of gruelling warfare follow. The area had barely recovered from previous wars and is now subject to even more destruction. New weapons - repeating rifles and high-explosive artillery - are used by both sides. The Roskians have more of these weapons, but the Amestrians are rallied by their nationalist ideology to defend their Empire (which had only recently come into being after the campaigns of Varik Taraskalic), and can field more men. They also have a tradition of military theory and leadership which the Roskians struggle to match (at the famous battle of [Krakow], the Amestrians manage to surround and capture an army of 35,000 Roskian soldiers complete with all their weapons and supplies).

After two years of manoeuvre warfare, with three hundred thousand casualties on the Amestrian side (and not much less on the Roskian side), the war begins to slow down. Trenches are dug, guarded by metal stakes and minefields (although machine-guns remain rare on this front, and barbed wire is yet to be invented). Still the Roskian leaders refuse any peace treaty, and continue to send in more troops and weapons, making gradual progress, but draining their manpower and almost bankrupting their empire in the process. Aarut-built airships are used to bomb Amestrian towns and cities by night. The brutality of the Rosk armies is condemned throughout much of Europe, and much sympathy is gained for the Amestrian cause. The peoples of Lanverg (northern Norway) press the Aarut leadership for sanctions against Rosk and for more liberal reforms, both unsuccessfully. The Amestrians begin to adopt Furotocan ideals and seek Furotocan support, out of desperation more than anything else. Any libertarians captured by the Roskians are summarily executed.

Refugees flee in all directions. The neighbouring Thessen Union remains officially neutral, but unofficially backs its fellow Amestrians in various ways, and forces the Roskians to keep a large garrison on the border.

In 1887, two flashpoints trigger a greater war. The first is near the northern borders of the Furotoca, deep inside Amestrian territory, where advancing Rosk armies begin skirmishing with Furotocans. The second is in former Taretara [Spain], where there is growing unrest over the uninspiring rule of Argine aristocrats, and also popular anger towards the Aarut for their annexation of old overseas colonies and their increasing influence in the home peninsular itself. The adoption of Furotocan ideals is an afterthought, a convenient common cause to rally round, but to the Aarut and Rosk it is seen as another example of the Furotocan efforts to destabilize Europe.

The Aarut send one of their old, ornate, large sailing warships, the Vilgaarstad, to escort the Archduke of Taretara (son of the Argine Emperor) and his family to safety. Allegedly, it is attacked by a rebel torpedo-boat, supplied to the rebels by the Furotocans. What is certain is that the Vilgaarstad[/I explodes and sinks with the deaths of most onboard, including the Archduke and his family. The Aarut and Argine people are outraged, and their leaders declare war on both the Taretaran rebels and the Furotocan alliance. Rosk also gives its support. The scale of the fighting soon exceeds anything yet seen in Europe.

In 1888, a combined Argine-Aarut army enters into the northern territories of the Furotoca and pillages several of their key industrial cities. Furotocan war-industry takes years to recover from this blow. But Argine army is in poor shape after a century of inactivity. The ill-equipped and ill-led Argine forces prove to be more of a liability for the Aarut than anything else. The Furotocans soon rally and expel the invasion (rushing reinforcements to the front by steam train), and send forces to aid the Amestrians, although they have to pull forces out of eastern Europe and [Turkey] from the fight against the Varakans. Battles are fought across [southern France] and [northern Italy] until the front stabilizes at roughly the original borders.

Aarut forces win famous victories, with the aid of machine-guns and superior artillery, but due to their colonial commitments they simply don't have enough men in Europe to hold on to their gains.

The fighting in Taretara becomes a protracted guerrilla war. The liberalist rebels enjoy popular support and eventually triumph, although at great cost in lives.

The Furotocans and their allies close the straights of [Gibraltar] with mines and artillery emplacements on the northern side. Given embarrassing losses of ships to the 'primitive' weapons of the Panto on the North American front, the Aarut admirals are not willing to risk forcing a way through the straights. The great modern warships of the Aarut fleet play little part in the Mediterranean, although they do prevent the Furotocans and their allies from receiving any trade from the Atlantic.

The fight between Roskian and Amestrian forces spills across the eastern border into Nadzavosk-Savizia, which is already engulfed in civil war.

After reaching all the way south into Furotocan territory, Roskian forces are finally exhausted and forced to retreat. In the process, the short-lived Amestrian Empire dissolves into a coalition of resistance forces with a mix of ideologies, known as the Amestrian Union.

The first awkward aerial combat takes place when steam-powered airships and blimps of the Furotocans and Aarut/Rosk begin to encounter each other in the skies over northern [Italy] and southern Amestria. The war also sees the first appearance of armoured, steam-powered, tracked vehicles, mostly built by the Aarut - but these perform poorly and are hardly used except in siege situations.

In 1895, the Peace of [Zurich], signed in the neutral Kingdom of Ustri, brings a temporary peace to Europe. The liberalists gain Taretara, creating new states there, while the islands of [Corsica] and [Sardinia] voluntarily join the Furotoca, and Rosk gains much of the former Amestrian Empire, some of which becomes a vassal state under the 'Kingdom of Amestria'. The final death toll from the 'Great War' is somewhere between two and four million combatants, plus an estimated one million civilians. Although, barely a year passes before the Roskians and Amestrians resume their conflict - an unofficial war continues into 1910, with hardened guerrilla forces and brutal tactics employed by both sides. Fighting within the Varakan Empire and Nadzavosk-Savizia also carries on for some time.

The Rosk Empire is weakened by loss of manpower, wealth and popularity. It is seen as a cruel militarist state and is widely blamed for causing the war in western and central Europe. The Poneb Empire gains greater influence in the [Baltic] and [Finland].

The Furotocan economy (and that of its allies) struggles to recover. Although patriotism is as high as ever, there are ongoing trade restrictions put in place by the Varakans and Aarut. Anti-war movements gain popularity, and there is little desire for any more military involvement in foreign lands.

The Argine Empire is shaken by the war, the loss of Taretara and the loss of its overseas colonies. After their initial outrage towards the liberalists passes, the Argine people press for moderate reforms. Their empire becomes a 'union' with a purely ceremonial monarch, and seeks a middle ground between the two main spheres of Europe.

Ustri, Thessen, Geldut and the Kronahar Kingdom, having remained neutral, are left in a stronger position than before, with comparatively greater wealth and manpower. Kronahar also gains from the arrival of Aarut industrial entrepreneurs, attracted by the country's plentiful coal and iron ore deposits. However, the war has also led to rapid progress of industry and technology by the various warring factions, in some ways going beyond the achievements of the Far East.

The peaceful anti-industrial spiritualist movement of 'Suloism' gains popularity in Ustri and the Furotoca, partly as a reaction to the war. It takes influences from Reformist-Wainist philosophy, ancient Targarotan cults, and the translated writings of the great Lantanist prophets of North America.

There are many discussions about uniting the Furotoca of Curias with the Orimudan Alliance. Many are not quite ready to accept such a change. Decades pass without a decision being made, although the two states become close allies. The northern powers of Aarut and Rosk become increasingly hostile towards them as their influence grows.

The Furotocans and their allies give full support to liberalist and democratic uprisings in eastern Europe, namely the Keyzad of Nadzavosk-Savizia and the Varakan Empire, leading to large-scale conflict from 1880 onwards. Furotocan ironclads and torpedo-boats defeat the Varakan [Mediterranean] fleet, which is left with only its few modern armoured cruisers to raid enemy supply lines (the building of a great canal between the Mediterranean and the [Red Sea] is still just an idea at this point, so the Varakans cannot deploy their mighty Indian Ocean fleet). Varakan forces are overstretched across their empire - despite the use of heavy artillery, machine-guns, and large airships for terror-bombing, they are ultimately unable to keep a hold on all their western territories.

Some uprisings are crushed, but after decades of fighting, several more liberalist states appear on the map - all of them are allied to the Furotocans and Orimudans, but few of them are very stable. Some refugees move into the Varakan Empire or Poneb, while others move to the Orimuda and Furotoca. Varakan knowledge of microbiology and the telegraph finds its way into Europe. The [Balkan] kingdoms of Varas and Arad (the 'Eastern Kingdoms') are the only ones to stubbornly resist the liberalists, and they form a small island of authoritarian rule.

But the spread of 'corrosive' liberalist ideas to the rest of Europe is basically an invention by Roskian and Aarut propagandists. The peasants of the Argine Empire remain apathetic, and the militarist-nationalism of the Amestrian Empire counters Furotocan influence in the north. Ironically, it is not until the Rosk Empire wages a brutal war on the Amestrians, supposedly to halt the spread of liberalist ideals, that those ideals actually gain more support across the rest of Europe.

The armies of Rosk invade the Amestrian Empire in 1885, and years of gruelling warfare follow. The area had barely recovered from previous wars and is now subject to even more destruction. New weapons - repeating rifles and high-explosive artillery - are used by both sides. The Roskians have more of these weapons, but the Amestrians are rallied by their nationalist ideology to defend their Empire (which had only recently come into being after the campaigns of Varik Taraskalic), and can field more men. They also have a tradition of military theory and leadership which the Roskians struggle to match (at the famous battle of [Krakow], the Amestrians manage to surround and capture an army of 35,000 Roskian soldiers complete with all their weapons and supplies).

After two years of manoeuvre warfare, with three hundred thousand casualties on the Amestrian side (and not much less on the Roskian side), the war begins to slow down. Trenches are dug, guarded by metal stakes and minefields (although machine-guns remain rare on this front, and barbed wire is yet to be invented). Still the Roskian leaders refuse any peace treaty, and continue to send in more troops and weapons, making gradual progress, but draining their manpower and almost bankrupting their empire in the process. Aarut-built airships are used to bomb Amestrian towns and cities by night. The brutality of the Rosk armies is condemned throughout much of Europe, and much sympathy is gained for the Amestrian cause. The peoples of Lanverg (northern Norway) press the Aarut leadership for sanctions against Rosk and for more liberal reforms, both unsuccessfully. The Amestrians begin to adopt Furotocan ideals and seek Furotocan support, out of desperation more than anything else. Any libertarians captured by the Roskians are summarily executed.

Refugees flee in all directions. The neighbouring Thessen Union remains officially neutral, but unofficially backs its fellow Amestrians in various ways, and forces the Roskians to keep a large garrison on the border.

In 1887, two flashpoints trigger a greater war. The first is near the northern borders of the Furotoca, deep inside Amestrian territory, where advancing Rosk armies begin skirmishing with Furotocans. The second is in former Taretara [Spain], where there is growing unrest over the uninspiring rule of Argine aristocrats, and also popular anger towards the Aarut for their annexation of old overseas colonies and their increasing influence in the home peninsular itself. The adoption of Furotocan ideals is an afterthought, a convenient common cause to rally round, but to the Aarut and Rosk it is seen as another example of the Furotocan efforts to destabilize Europe.

The Aarut send one of their old, ornate, large sailing warships, the Vilgaarstad, to escort the Archduke of Taretara (son of the Argine Emperor) and his family to safety. Allegedly, it is attacked by a rebel torpedo-boat, supplied to the rebels by the Furotocans. What is certain is that the Vilgaarstad[/I explodes and sinks with the deaths of most onboard, including the Archduke and his family. The Aarut and Argine people are outraged, and their leaders declare war on both the Taretaran rebels and the Furotocan alliance. Rosk also gives its support. The scale of the fighting soon exceeds anything yet seen in Europe.

In 1888, a combined Argine-Aarut army enters into the northern territories of the Furotoca and pillages several of their key industrial cities. Furotocan war-industry takes years to recover from this blow. But Argine army is in poor shape after a century of inactivity. The ill-equipped and ill-led Argine forces prove to be more of a liability for the Aarut than anything else. The Furotocans soon rally and expel the invasion (rushing reinforcements to the front by steam train), and send forces to aid the Amestrians, although they have to pull forces out of eastern Europe and [Turkey] from the fight against the Varakans. Battles are fought across [southern France] and [northern Italy] until the front stabilizes at roughly the original borders.

Aarut forces win famous victories, with the aid of machine-guns and superior artillery, but due to their colonial commitments they simply don't have enough men in Europe to hold on to their gains.

The fighting in Taretara becomes a protracted guerrilla war. The liberalist rebels enjoy popular support and eventually triumph, although at great cost in lives.

The Furotocans and their allies close the straights of [Gibraltar] with mines and artillery emplacements on the northern side. Given embarrassing losses of ships to the 'primitive' weapons of the Panto on the North American front, the Aarut admirals are not willing to risk forcing a way through the straights. The great modern warships of the Aarut fleet play little part in the Mediterranean, although they do prevent the Furotocans and their allies from receiving any trade from the Atlantic.

The fight between Roskian and Amestrian forces spills across the eastern border into Nadzavosk-Savizia, which is already engulfed in civil war.

After reaching all the way south into Furotocan territory, Roskian forces are finally exhausted and forced to retreat. In the process, the short-lived Amestrian Empire dissolves into a coalition of resistance forces with a mix of ideologies, known as the Amestrian Union.

The first awkward aerial combat takes place when steam-powered airships and blimps of the Furotocans and Aarut/Rosk begin to encounter each other in the skies over northern [Italy] and southern Amestria. The war also sees the first appearance of armoured, steam-powered, tracked vehicles, mostly built by the Aarut - but these perform poorly and are hardly used except in siege situations.

In 1895, the Peace of [Zurich], signed in the neutral Kingdom of Ustri, brings a temporary peace to Europe. The liberalists gain Taretara, creating new states there, while the islands of [Corsica] and [Sardinia] voluntarily join the Furotoca, and Rosk gains much of the former Amestrian Empire, some of which becomes a vassal state under the 'Kingdom of Amestria'. The final death toll from the 'Great War' is somewhere between two and four million combatants, plus an estimated one million civilians. Although, barely a year passes before the Roskians and Amestrians resume their conflict - an unofficial war continues into 1910, with hardened guerrilla forces and brutal tactics employed by both sides. Fighting within the Varakan Empire and Nadzavosk-Savizia also carries on for some time.

The Rosk Empire is weakened by loss of manpower, wealth and popularity. It is seen as a cruel militarist state and is widely blamed for causing the war in western and central Europe. The Poneb Empire gains greater influence in the [Baltic] and [Finland].

The Furotocan economy (and that of its allies) struggles to recover. Although patriotism is as high as ever, there are ongoing trade restrictions put in place by the Varakans and Aarut. Anti-war movements gain popularity, and there is little desire for any more military involvement in foreign lands.

The Argine Empire is shaken by the war, the loss of Taretara and the loss of its overseas colonies. After their initial outrage towards the liberalists passes, the Argine people press for moderate reforms. Their empire becomes a 'union' with a purely ceremonial monarch, and seeks a middle ground between the two main spheres of Europe.

Ustri, Thessen, Geldut and the Kronahar Kingdom, having remained neutral, are left in a stronger position than before, with comparatively greater wealth and manpower. Kronahar also gains from the arrival of Aarut industrial entrepreneurs, attracted by the country's plentiful coal and iron ore deposits. However, the war has also led to rapid progress of industry and technology by the various warring factions, in some ways going beyond the achievements of the Far East.

The peaceful anti-industrial spiritualist movement of 'Suloism' gains popularity in Ustri and the Furotoca, partly as a reaction to the war. It takes influences from Reformist-Wainist philosophy, ancient Targarotan cults, and the translated writings of the great Lantanist prophets of North America.

Daftpanzer

canonically ambiguous

Spoiler THE REST :

AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE-EAST:

Tezan's leaders refuse to become entangled in Taretara [Spain], and abandon their last few enclaves to be fought over by others. While it is feared the Furotocans have ambitions in North Africa, there is basically no popular support for their liberal ideals. Conservative, orthodox-Wainist traditions remain entrenched throughout Tezan's empire.

Peace with the Varakans and Furotocans gives Tezan a free hand to push further into north-western Africa. Another incentive is the turmoil in the Mediterranean - as the straights of [Gibraltar] are closed off, the ports on the Atlantic coast become more important. The armies of Tezan are barely better equipped than the neighbouring African states, but they have the advantage of greater organization and large amounts of gold to bribe their enemies. The Awi and Jologi kingdoms soon disappear from the map, while other states become vassals and protectorates. By 1910 only the Hawaladu kingdoms remain openly defiant of Tezan.

Tezan also expands into southern Africa. As the Saikaran [south Japanese] and Argine colonies in Africa fall into turmoil due to events elsewhere, Tezan absorbs them under a cosmopolitan vassal state, the so-called Saigara Bahila, which soon becomes famous for violence, corruption and occasionally abundant wealth.

With the aid of advisors and weapons from south-east Asia, the Hom Empire reclaims its former territory on the mainland, and expands further. By 1895 it is in position to claim sole authority over the southern Nacubian lands, formerly shared with Saikara (although much Takaraji [Japanese] influence remains). Aarut settlers and traders also begin to arrive in Nacubia, becoming an influential minority there by 1910.

Hom establishes colonies in southern [Australia] after 1895. Many of the colonists are actually Zhul peoples from Ceyloni and Zhulhara [southern India], or Aarut adventurers from Nacubia.

The remnants of Hom rebels and various other powers defeated by the Hom Empire are absorbed into the Timuru Empire, which rises from one of the minor Haburu kingdoms in little more than a decade. Although comparatively 'primitive', Haburu can field a large army and seems to be a threat to both the Hom territories and the new Tezanian colonies in the west.

Hom's borders reach up to the Manzuru Empire and tension grows between the two states. Manzuru continues to play host to many notable foreigners, including Varakan industrialists. The army is steadily modernized. More territory and influence is gained in central Africa. Several neighbouring kingdoms agree to become protectorates.

The Varakan Empire and its vassals take greater control of the [Arabian Peninsular], though the Nayir tribes remain a threat and cause costly damage to Varakan railways and prospecting camps. There is also growing unrest among the peoples of the Garakal Katanates.

Apart from increased Varakan military activity, the ancient land of Yansala is left as a quiet backwater. Varakan archaeologists begin to document the ruins of long-forgotten Pargian kingdoms and empires.

Acting against official orders, the commander of Varakan garrisons in southern Yansala takes a thousand horsemen armed with repeating rifles, and claims large tracts of land west of the [Nile] in the name of Varaka. This causes some tension with Tezan and its affiliated tribes in the nearby desert.

INDIA AND ASIA:

Poneb benefits from the war in Europe, gaining influence in the [Baltic] and Nadzavosk-Savisia. But it suddenly faces the onset of civil war in 1901. Although there is some unrest among the various eastern peoples, the rebellion can really be blamed on the charisma and brutal determination of Varyk Leksandsy, a man born to a poor ethnic-Sarvonian peasant family on the expanding eastern borders of the empire (he later claims ancestry from famous Sarvonian and Ponebian leaders but this is never proven). Leksandsy's rebellion is a tale of inspired leadership and stunning betrayal. It is also tale of careful exploitation of shared fear and anger towards the Poneb and Marzhung empires.

In 1901, after gaining influence over the Vonoth kingdom, Leksandsy marches west and encourages the Sezat people to rise up against Poneb's rule. In the following years, there are victories against punitive expeditions sent by Poneb, which either encourages or intimidates more of the north-eastern peoples into joining Leksandsy's cause. Disaffected Marzhung warlords are also tempted north to join the rebellion, brining with them some modern Varakan weapons.

Eventually, Leksandsy is himself betrayed and assassinated. But his coalition remains largely intact, not least because of the shared threat of capture and death at the hands of Poneb. In 1907, at the town of Sezvyr, most of Leksandsy's former allies and lieutenants make a pact to carry on the fight, and vow to build a new empire in the east, borrowing just a little from libertarian ideas of both the Furotocans and the Yanshi Republic of the far-east.

The 'Sezvyr Covenant' never seems far from collapse into anarchy, but by 1910 it is still holding together, and the fighting continues. The epic distances involved helping to slow things down, although Poneb loyalists have control of the empire's industrial sites in the west, and have the use of its expanding rail network.

The Sezvyr try to gain support from the southern Sarvonians in the Keyzad of Nadzavosk-Savisia. But after suffering from Furotocan-backed uprisings which came close to overrunning the whole country, the western Keyzad is left in a weak state, and comes under the joint influence of Varaka (via the Marzhung) and Poneb.

---

Marozhung III, the latest so-called emperor of Marzhung, opens his doors to Varakan influence and surrounds himself with Varakan and pro-Varakan advisors. This is generally approved of, due to popular antagonism towards Poneb and Nadzavosk-Savisia. Varakan troops help stabilize the borders (apart from the north, where borders are more chaotic) and gradually help Marozhung III unite the various Marzhung factions under his authority. In return, Varakan industrialists gain access to Marzhung territory and resources. Varakan railroads and infrastructure spread across the country. By 1910, the 'Great Keyzad' is a firm ally and unofficial vassal state of Varaka.

The Marzhung are happy to let Poneb and Sezvyr fight amongst themselves, although both Marzhung and Varakan troops help suppress the revolutions in Nadzavosk-Savisia.

During the long reign of Empress Taina IV, the Varakan Empire goes through several crises of confidence. There is almost an expectation of decline and collapse. The Furotocan-backed uprisings in the western territories cause the loss of several of the empire's important industrial centres, along with some of its best engineers and scientists. Some factions call for the conscription of millions of troops for a full-scale war against the Furotocan sphere, while others call for a radical division of the empire into small reformist states. Taina IV and her advisors favour a cautious approach. The empire deploys every modern weapon at its disposal, but otherwise conserves its strength. By 1910 confidence begins to return

In theory, the Varakans are allies of the Aarut and Rosk in their struggle against the Furotocan sphere. Aarut envoys are present in the Varakan capitol, but otherwise there is no real cooperation. The Varakans still regard the northern Europeans as somewhat primitive.

Liberalism, Krashenism and other 'dangerous' ideas spread into the heartland of the empire. But the sheer diversity of different customs and cultures serves to divide the dissenters into small and insignificant groups. The imperial ideal remains the only unifying factor at this point.

Partly as a reaction to western uprisings, there is a revival of interest in eastern Yeuren culture and literature, which had been carried into central Asia by various steppe empires over the centuries.

As the situation in [northern India] deteriorates, the Varakans begin to lose interest and gradually fall back to the more stable parts of Tanyuria.

Despite the official stance of holding the borders, the empire continues to expand in certain places (Pargia and the Irzhul Katan), almost by accident. Varakan colonies begin to appear in the Indian Ocean, following the problems of the Takaraji [Japanese]. Other colonies are then founded in the southern Atlantic islands and eastern Australia, funded by private industrialists and merchant-houses.

Industry continues to take hold. Varakan prospectors begin to uncover the true extent of oil reserves in their empire. There are experiments with refining oil on a large scale, and using it to replace coal as a fuel for steam engines, especially onboard ships.

The Varakans have the resources to build the largest airships of the time - although some are lost in horrific accidents, others make many successful journeys to neighbouring countries, and have great propaganda value.

The invention of the telegraph is disputed between east and west, but again it is the Varakans who are the first use the technology on a large scale, with considerable benefits when it comes to controlling their territories.

---

In the Grajaj territories, the philosopher known as Krashenis Marumba publishes his famous works on social and political theory, stating that power should be taken by the ordinary people, with wealth and property distributed fairly and according to need. 'Krashenism' begins to gain support among the people, but conservatives try to suppress it, and eventually the Krashenist factions split off from the Grajaj leadership.

The eastern Tiandulong states become entangled in the fighting. The struggle against the Varakan Empire breaks down into a bitter four-way guerrilla war. Small forces fight each other, often in difficult terrain, using a wide range of old and new weapons. Some important cities and forts change hands almost every year. Although, both the Grajaj and the Krashenists style themselves as defenders of the people. Special care is taken to protect the old temples and monuments of the former Kaj and Guraj empires.

The Zhulhara Alliance does its best to remain neutral. It quietly absorbs some of the less-radical Krashenist ideals and spreads them around the Indian Ocean.

An independent Ceyloni kingdom reappears. It maintains close relations with both the Takaraji [Japanese] and the east-African empires.

In 1909, a deadly new outbreak of plague occurs around the [Bay of Bengal] and begins to spread across India, and across the Indian Ocean. The Varakans turn to chemistry and microbiology in the search for a cure.

EAST ASIA:

Most of the far eastern powers fight each other at some point between 1875 and 1910, but none wishes a full-scale war of the kind seen in Europe and North America. These wars are fairly small in scale, some no more than skirmishes. Nonetheless, there remains the potential for the biggest war yet known. The far-eastern powers can call upon greater manpower and, at least until 1900, deadlier weapons than the rest of the world.

The Yanshi Republic continues its rivalry with the Takaraji [Japanese] factions. A naval arms-race begins. All sides build large metal-hulled ships, but there is disagreement about what kind of speed, armour and firepower are needed. The result is a great variety of ship designs, from small torpedo-boats to large, near-circular 'mobile fortresses'.

In 1883, before the expected Yanshi-Takaraji war can begin, an unexpected war breaks out between the Takaraji factions. By this time the political situation of the home islands has become extremely complex and treacherous. If there is a single main cause for the war, it is the overconfidence of the Tekoda [central Japanese] faction and their attempts to gain greater influence over the others. In any case the Tekoda find themselves betrayed and attacked by their rivals. Battles are fought across [Indonesia] and the south-west Pacific, but the war in the home islands becomes almost ceremonial. The most powerful siege-guns in the world are built for this war, but the generals of the various factions are ultimately unwilling to use them against their intended targets - the ornate medieval castles still used as headquarters and places of residence for the nobility.

In 1886, after several years of siege, stalemate and political wrangling, a major naval battle off the coast of [Mindanao] finally forces the issue. The main Tekoda battle fleet is crippled by a combined fleet of Suraji and Saikara. Various foreign privateers and observers also take part - the Yanshi note with interest how heavy-calibre guns prove decisive, even if few in number.

In 1887, the Tekoda faction is disbanded in agreement with the ceremonial emperor of Takaraji. Suraji and Saikara attempt to divide the spoils, but the colonies in [Indonesia] and the Indian Ocean have been thrown into turmoil. Yanshi finally commits to an 'unofficial' war against the remaining Takaraji factions, with the aim of 'liberating' large parts of their colonial empire.

Like the Furotocans in the Mediterranean, the Yanshi encourage liberalist and nationalist uprisings throughout [Indonesia], and gain influence among the new states. Naval skirmishes are fought with the Saikara especially. The arms-race gathers pace when the Yanshi show off their latest, all-heavy-gun warships, with deadly results.

The Saikara ultimately lose control over many territories (including the crucial Straights of [Malacca]), but make gains elsewhere, including [Australia] - where rumours of gold and precious minerals have begun to attract other colonists, including Varakans, Hom, and the Yanshi who make an alliance with the Pahay tribes of the south.

By 1910 there is a unified Dagon kingdom in southern [Borneo], with ambitions to reunite [Indonesia], although the region now has a great mixture of peoples from Asia and east Africa.

The Yanshi and Takaraji also begin experimenting with large electric motors and internal-combustion engines. Takaraji inventors dream of fast-moving, heavier-than-air flying machines to unite their island territories. The principles of aerodynamics are understood, but a suitable lightweight power source has yet to be built.

The 'barbarian' Akuden Empire [Manchuria] collapses under the pressure of its powerful neighbours. The scramble for its former territory is mostly won by the Varakans, with the aid of their Marzhung allies. The Irzhul peoples are made into another Katan (Varakan vassal state).

Holy Emperor Feng-Hasham begins a campaign of aggressively expanding Shynist influence, contributing to the collapse of the Akuden Empire. But, ultimately this leads to a short war with the Tiandishi. Shyin's efforts fail against better-equipped Tiandishi forces, and some land is lost. Shynism is increasingly persecuted in the Tiandishi Empire, which is now dominated by Mingdebuists. But elsewhere the prestige of Shynism is increased - more converts are gained from the eastern Varakan Empire especially.

The Shyin Empire tightens its grip on the vassal states of Hayata and Nadal. Shyin traditionalism forms a barrier to the northward spread of Krashenist influence from India.

Shynists migrate from India and Tiandishi begin to migrate to the Siyaga Kingdom [Thailand]. There they form an influential community known as the Litarotangs or 'The Free Ones'. Their liberalist ideas are similar to the Furotoca and Yanshi. They help to undermine Takaraji imperialism in south-east Asia, out of which the Siyaga Kingdom gains new territory.

The Tiandishi gain the Yienvai and Naga kingdoms as vassal states, and begin to see themselves as the true inheritors of all the glorious ancient empires of the east. While there is a revival of their own culture, there is also renewed interest in Tuizen traditions. Advisors at the Tiandhsi court revive the philosophy of Quandao, preaching that brutal and unsentimental pragmatism is the only way for rulers to maintain peace and order.

The Tiandishi Empire remains behind the Yanshi and Takaraji in terms of technology, but makes gradual progress.

Apart from the Dai Gedeba theocracy in [Indonesia] and some other isolated areas, the wave of Mingdebu fanaticism continues to subside.

Tezan's leaders refuse to become entangled in Taretara [Spain], and abandon their last few enclaves to be fought over by others. While it is feared the Furotocans have ambitions in North Africa, there is basically no popular support for their liberal ideals. Conservative, orthodox-Wainist traditions remain entrenched throughout Tezan's empire.

Peace with the Varakans and Furotocans gives Tezan a free hand to push further into north-western Africa. Another incentive is the turmoil in the Mediterranean - as the straights of [Gibraltar] are closed off, the ports on the Atlantic coast become more important. The armies of Tezan are barely better equipped than the neighbouring African states, but they have the advantage of greater organization and large amounts of gold to bribe their enemies. The Awi and Jologi kingdoms soon disappear from the map, while other states become vassals and protectorates. By 1910 only the Hawaladu kingdoms remain openly defiant of Tezan.

Tezan also expands into southern Africa. As the Saikaran [south Japanese] and Argine colonies in Africa fall into turmoil due to events elsewhere, Tezan absorbs them under a cosmopolitan vassal state, the so-called Saigara Bahila, which soon becomes famous for violence, corruption and occasionally abundant wealth.

With the aid of advisors and weapons from south-east Asia, the Hom Empire reclaims its former territory on the mainland, and expands further. By 1895 it is in position to claim sole authority over the southern Nacubian lands, formerly shared with Saikara (although much Takaraji [Japanese] influence remains). Aarut settlers and traders also begin to arrive in Nacubia, becoming an influential minority there by 1910.

Hom establishes colonies in southern [Australia] after 1895. Many of the colonists are actually Zhul peoples from Ceyloni and Zhulhara [southern India], or Aarut adventurers from Nacubia.

The remnants of Hom rebels and various other powers defeated by the Hom Empire are absorbed into the Timuru Empire, which rises from one of the minor Haburu kingdoms in little more than a decade. Although comparatively 'primitive', Haburu can field a large army and seems to be a threat to both the Hom territories and the new Tezanian colonies in the west.

Hom's borders reach up to the Manzuru Empire and tension grows between the two states. Manzuru continues to play host to many notable foreigners, including Varakan industrialists. The army is steadily modernized. More territory and influence is gained in central Africa. Several neighbouring kingdoms agree to become protectorates.

The Varakan Empire and its vassals take greater control of the [Arabian Peninsular], though the Nayir tribes remain a threat and cause costly damage to Varakan railways and prospecting camps. There is also growing unrest among the peoples of the Garakal Katanates.

Apart from increased Varakan military activity, the ancient land of Yansala is left as a quiet backwater. Varakan archaeologists begin to document the ruins of long-forgotten Pargian kingdoms and empires.

Acting against official orders, the commander of Varakan garrisons in southern Yansala takes a thousand horsemen armed with repeating rifles, and claims large tracts of land west of the [Nile] in the name of Varaka. This causes some tension with Tezan and its affiliated tribes in the nearby desert.

INDIA AND ASIA:

Poneb benefits from the war in Europe, gaining influence in the [Baltic] and Nadzavosk-Savisia. But it suddenly faces the onset of civil war in 1901. Although there is some unrest among the various eastern peoples, the rebellion can really be blamed on the charisma and brutal determination of Varyk Leksandsy, a man born to a poor ethnic-Sarvonian peasant family on the expanding eastern borders of the empire (he later claims ancestry from famous Sarvonian and Ponebian leaders but this is never proven). Leksandsy's rebellion is a tale of inspired leadership and stunning betrayal. It is also tale of careful exploitation of shared fear and anger towards the Poneb and Marzhung empires.

In 1901, after gaining influence over the Vonoth kingdom, Leksandsy marches west and encourages the Sezat people to rise up against Poneb's rule. In the following years, there are victories against punitive expeditions sent by Poneb, which either encourages or intimidates more of the north-eastern peoples into joining Leksandsy's cause. Disaffected Marzhung warlords are also tempted north to join the rebellion, brining with them some modern Varakan weapons.

Eventually, Leksandsy is himself betrayed and assassinated. But his coalition remains largely intact, not least because of the shared threat of capture and death at the hands of Poneb. In 1907, at the town of Sezvyr, most of Leksandsy's former allies and lieutenants make a pact to carry on the fight, and vow to build a new empire in the east, borrowing just a little from libertarian ideas of both the Furotocans and the Yanshi Republic of the far-east.

The 'Sezvyr Covenant' never seems far from collapse into anarchy, but by 1910 it is still holding together, and the fighting continues. The epic distances involved helping to slow things down, although Poneb loyalists have control of the empire's industrial sites in the west, and have the use of its expanding rail network.

The Sezvyr try to gain support from the southern Sarvonians in the Keyzad of Nadzavosk-Savisia. But after suffering from Furotocan-backed uprisings which came close to overrunning the whole country, the western Keyzad is left in a weak state, and comes under the joint influence of Varaka (via the Marzhung) and Poneb.

---

Marozhung III, the latest so-called emperor of Marzhung, opens his doors to Varakan influence and surrounds himself with Varakan and pro-Varakan advisors. This is generally approved of, due to popular antagonism towards Poneb and Nadzavosk-Savisia. Varakan troops help stabilize the borders (apart from the north, where borders are more chaotic) and gradually help Marozhung III unite the various Marzhung factions under his authority. In return, Varakan industrialists gain access to Marzhung territory and resources. Varakan railroads and infrastructure spread across the country. By 1910, the 'Great Keyzad' is a firm ally and unofficial vassal state of Varaka.

The Marzhung are happy to let Poneb and Sezvyr fight amongst themselves, although both Marzhung and Varakan troops help suppress the revolutions in Nadzavosk-Savisia.

During the long reign of Empress Taina IV, the Varakan Empire goes through several crises of confidence. There is almost an expectation of decline and collapse. The Furotocan-backed uprisings in the western territories cause the loss of several of the empire's important industrial centres, along with some of its best engineers and scientists. Some factions call for the conscription of millions of troops for a full-scale war against the Furotocan sphere, while others call for a radical division of the empire into small reformist states. Taina IV and her advisors favour a cautious approach. The empire deploys every modern weapon at its disposal, but otherwise conserves its strength. By 1910 confidence begins to return

In theory, the Varakans are allies of the Aarut and Rosk in their struggle against the Furotocan sphere. Aarut envoys are present in the Varakan capitol, but otherwise there is no real cooperation. The Varakans still regard the northern Europeans as somewhat primitive.

Liberalism, Krashenism and other 'dangerous' ideas spread into the heartland of the empire. But the sheer diversity of different customs and cultures serves to divide the dissenters into small and insignificant groups. The imperial ideal remains the only unifying factor at this point.

Partly as a reaction to western uprisings, there is a revival of interest in eastern Yeuren culture and literature, which had been carried into central Asia by various steppe empires over the centuries.

As the situation in [northern India] deteriorates, the Varakans begin to lose interest and gradually fall back to the more stable parts of Tanyuria.

Despite the official stance of holding the borders, the empire continues to expand in certain places (Pargia and the Irzhul Katan), almost by accident. Varakan colonies begin to appear in the Indian Ocean, following the problems of the Takaraji [Japanese]. Other colonies are then founded in the southern Atlantic islands and eastern Australia, funded by private industrialists and merchant-houses.

Industry continues to take hold. Varakan prospectors begin to uncover the true extent of oil reserves in their empire. There are experiments with refining oil on a large scale, and using it to replace coal as a fuel for steam engines, especially onboard ships.

The Varakans have the resources to build the largest airships of the time - although some are lost in horrific accidents, others make many successful journeys to neighbouring countries, and have great propaganda value.

The invention of the telegraph is disputed between east and west, but again it is the Varakans who are the first use the technology on a large scale, with considerable benefits when it comes to controlling their territories.

---

In the Grajaj territories, the philosopher known as Krashenis Marumba publishes his famous works on social and political theory, stating that power should be taken by the ordinary people, with wealth and property distributed fairly and according to need. 'Krashenism' begins to gain support among the people, but conservatives try to suppress it, and eventually the Krashenist factions split off from the Grajaj leadership.

The eastern Tiandulong states become entangled in the fighting. The struggle against the Varakan Empire breaks down into a bitter four-way guerrilla war. Small forces fight each other, often in difficult terrain, using a wide range of old and new weapons. Some important cities and forts change hands almost every year. Although, both the Grajaj and the Krashenists style themselves as defenders of the people. Special care is taken to protect the old temples and monuments of the former Kaj and Guraj empires.

The Zhulhara Alliance does its best to remain neutral. It quietly absorbs some of the less-radical Krashenist ideals and spreads them around the Indian Ocean.

An independent Ceyloni kingdom reappears. It maintains close relations with both the Takaraji [Japanese] and the east-African empires.

In 1909, a deadly new outbreak of plague occurs around the [Bay of Bengal] and begins to spread across India, and across the Indian Ocean. The Varakans turn to chemistry and microbiology in the search for a cure.

EAST ASIA:

Most of the far eastern powers fight each other at some point between 1875 and 1910, but none wishes a full-scale war of the kind seen in Europe and North America. These wars are fairly small in scale, some no more than skirmishes. Nonetheless, there remains the potential for the biggest war yet known. The far-eastern powers can call upon greater manpower and, at least until 1900, deadlier weapons than the rest of the world.

The Yanshi Republic continues its rivalry with the Takaraji [Japanese] factions. A naval arms-race begins. All sides build large metal-hulled ships, but there is disagreement about what kind of speed, armour and firepower are needed. The result is a great variety of ship designs, from small torpedo-boats to large, near-circular 'mobile fortresses'.

In 1883, before the expected Yanshi-Takaraji war can begin, an unexpected war breaks out between the Takaraji factions. By this time the political situation of the home islands has become extremely complex and treacherous. If there is a single main cause for the war, it is the overconfidence of the Tekoda [central Japanese] faction and their attempts to gain greater influence over the others. In any case the Tekoda find themselves betrayed and attacked by their rivals. Battles are fought across [Indonesia] and the south-west Pacific, but the war in the home islands becomes almost ceremonial. The most powerful siege-guns in the world are built for this war, but the generals of the various factions are ultimately unwilling to use them against their intended targets - the ornate medieval castles still used as headquarters and places of residence for the nobility.

In 1886, after several years of siege, stalemate and political wrangling, a major naval battle off the coast of [Mindanao] finally forces the issue. The main Tekoda battle fleet is crippled by a combined fleet of Suraji and Saikara. Various foreign privateers and observers also take part - the Yanshi note with interest how heavy-calibre guns prove decisive, even if few in number.

In 1887, the Tekoda faction is disbanded in agreement with the ceremonial emperor of Takaraji. Suraji and Saikara attempt to divide the spoils, but the colonies in [Indonesia] and the Indian Ocean have been thrown into turmoil. Yanshi finally commits to an 'unofficial' war against the remaining Takaraji factions, with the aim of 'liberating' large parts of their colonial empire.

Like the Furotocans in the Mediterranean, the Yanshi encourage liberalist and nationalist uprisings throughout [Indonesia], and gain influence among the new states. Naval skirmishes are fought with the Saikara especially. The arms-race gathers pace when the Yanshi show off their latest, all-heavy-gun warships, with deadly results.

The Saikara ultimately lose control over many territories (including the crucial Straights of [Malacca]), but make gains elsewhere, including [Australia] - where rumours of gold and precious minerals have begun to attract other colonists, including Varakans, Hom, and the Yanshi who make an alliance with the Pahay tribes of the south.

By 1910 there is a unified Dagon kingdom in southern [Borneo], with ambitions to reunite [Indonesia], although the region now has a great mixture of peoples from Asia and east Africa.

The Yanshi and Takaraji also begin experimenting with large electric motors and internal-combustion engines. Takaraji inventors dream of fast-moving, heavier-than-air flying machines to unite their island territories. The principles of aerodynamics are understood, but a suitable lightweight power source has yet to be built.

The 'barbarian' Akuden Empire [Manchuria] collapses under the pressure of its powerful neighbours. The scramble for its former territory is mostly won by the Varakans, with the aid of their Marzhung allies. The Irzhul peoples are made into another Katan (Varakan vassal state).

Holy Emperor Feng-Hasham begins a campaign of aggressively expanding Shynist influence, contributing to the collapse of the Akuden Empire. But, ultimately this leads to a short war with the Tiandishi. Shyin's efforts fail against better-equipped Tiandishi forces, and some land is lost. Shynism is increasingly persecuted in the Tiandishi Empire, which is now dominated by Mingdebuists. But elsewhere the prestige of Shynism is increased - more converts are gained from the eastern Varakan Empire especially.

The Shyin Empire tightens its grip on the vassal states of Hayata and Nadal. Shyin traditionalism forms a barrier to the northward spread of Krashenist influence from India.

Shynists migrate from India and Tiandishi begin to migrate to the Siyaga Kingdom [Thailand]. There they form an influential community known as the Litarotangs or 'The Free Ones'. Their liberalist ideas are similar to the Furotoca and Yanshi. They help to undermine Takaraji imperialism in south-east Asia, out of which the Siyaga Kingdom gains new territory.

The Tiandishi gain the Yienvai and Naga kingdoms as vassal states, and begin to see themselves as the true inheritors of all the glorious ancient empires of the east. While there is a revival of their own culture, there is also renewed interest in Tuizen traditions. Advisors at the Tiandhsi court revive the philosophy of Quandao, preaching that brutal and unsentimental pragmatism is the only way for rulers to maintain peace and order.

The Tiandishi Empire remains behind the Yanshi and Takaraji in terms of technology, but makes gradual progress.

Apart from the Dai Gedeba theocracy in [Indonesia] and some other isolated areas, the wave of Mingdebu fanaticism continues to subside.

Notes:

Its now 1910 AD.

@Nick014, if you see this, I meant to reply about something - the divides amongst the Panto are between the 'pure' tribes and those who mixed with those outside cultures you've conquered or allied with over the centuries. Also, I realize I messed up your orders this time about who was supposed to unite with whom… I decided just to go with it, hope its not too offensive

Cultures and Factions Ownership:

Spoiler show :

Please feel free to ignore stuff, and only send orders/input for anything you are interested in. For unclaimed cultures, please check the first post in this thread.

tuxedohamm: (Colmassa culture)

Major influence: Colmassa Kingdoms, Amasa Empire

Lesser influence: Matac Kingdom, Zanac Kingdom

Masada: (Marzhung culture)

Major influence: Great Keyzad of Marzhung

Lesser influence: Keyzad of Nadzavosk-Savisia

El Naranja: (Anucat culture)

Major influence: Zamarac Kingdom, Anukarac Kingdoms, Anucat Chiefdoms

qoou: (Olan culture)

Major influence: Imperial Aarut Republic, Rosk Empire, Poneb Empire

Lesser influence: Argine Union, Nacubia, Republic of Nemarthia

Warhead: (Bretoch culture)

Major influence: Kronahar Kingdom

Lesser influence: Rithland, Marith Union

Crezth: (Amestrian culture)

Major influence: Amestrian Union, Thessen Union

Lesser influence: Rosk Empire, Ustri Kingdom, Imperial Aarut Republic, Sezvyr Covenant, Poneb Empire

Lord_Iggy: (Sarvonian culture)

Major influence: The Furotoca of Curias, Keyzad of Nadzavosk-Savisia, Keyzad of Urgury, Thuratica of South Savisia

Lesser influence: Holy Yansalan Kingdom, Garakal Katanates, Holy Tezan Empire, Great Keyzad of Marzhung, Thuratica of Zevon, Sezvyr Covenant, Zanac Kingdom

Ninja Dude: (Kramtob culture)

Major influence: Holy Shyin Empire, Grajaj Alliance, Krashenist Alliance

Lesser influence: Furotoca of Cheguia, Varakan Empire, The Furotoca of Curias, Argine Union, Keyzad of Urgury, Siyaga Kingdom

Charles Li: (Hsin-Yuan culture)

Major influence: Yanshi Republic

Lesser influence: Huiyan Allliance, Great Sarih Katanate, Zayan Kingdom

Luckymoose: (Agrian culture)

Major influence: Varakan Empire

Lesser influence: Zulhara Alliance, Great Keyzad of Marzhung

mythmonster2: (Zul cutlure)

Major influence: Hom Empire, Manzuru Empire, Saikara, Great Dagon Kingdom, Ulayasamat Kingdom, Zulyan/Zuli Tribes

Lesser influence: Garakal Katanates, Zulhara Alliance, Zayan Kingdom, Dai Gedeba, Ceyloni Kingdom

KrimzonStriker: (Toshion culture)

Major influence: Saikara, Suraji

Lesser influence: Waeluta Chiefdoms, Samaia Kingdom, Juray Kingdom, Zayan Kingdom, Ceyloni Kingdom

Bestshot9: (Washagon culture)

Major influence: Washagon Tribes, Tagon Kingdoms, Hachago Empire, Asuat Tribes, Waeluta Tribes/Chiefdoms, Asalyat Kingdom

Lesser influence: Aarut Empire, Suraji

Nick014: (Xanto culture)

Major influence: Xante States, Antehauta Empire, Panto Republic

Lesser influence: Xanauk Kingdoms, Lantamac Empire, Dahukat Kingdoms

human-slaughter: (Mavan culture)

Major influence: Orimudian Alliance

Lesser influence: The Furotoca of Curias, Sumetche Katad, Varas Kingdom, Kingdom of Pelonar, Turun Republic

LightFang: (Tianshi culture)

Major influence: Tiandishi Empire

Lesser influence: Tiandulong Tribes, Yienvai Kingdom, Siyaga Kingdom, Dai Gedeba

Next Era:

I would like to mention that technology could progress surprisingly fast, and there could be a kind of mixed up world war situation which would fit somewhere between ww1 and ww2 in real history. I would like to know what kind of political ideology your country/countries support, and who you would prefer to be allied with.

I would also say that its OK not to be an industrial superpower at this point, as more opportunities will probably come later, and you can just keep your great culture alive for now

NEW PEOPLE CAN STILL TAKE PART, there's probably some culture/country for every flavour, although not necessarily a great power

Luckymoose

The World is Mine

Varakan Empire is a conservative economically and liberal socially nation with a full election cycle for provinces, parliament and other forms of office. The monarchy holds a veto over every action, but generally stands back and allows our highly educated politicians do the work. I would like to be allied with Aarut, Nadzavosk-Savia and Manzuru. I would prefer to be enemies with Argine, Curias, and Tezan. With conflicts on all borders.

Orders for Varaka: