Genghis the Barbarian

Chieftain

- Joined

- Jan 19, 2021

- Messages

- 61

S3P2 Writeup

Probably the most shocking result I have ever gotten. This remains and will probably remain my all time favorite set ever.

Overview

To use my best Sullla voice: Whaaaaaaaaaaaaaaat?!?!?!

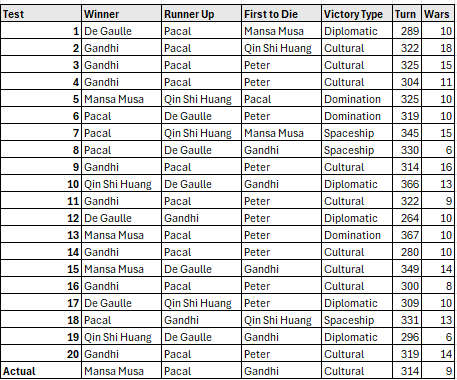

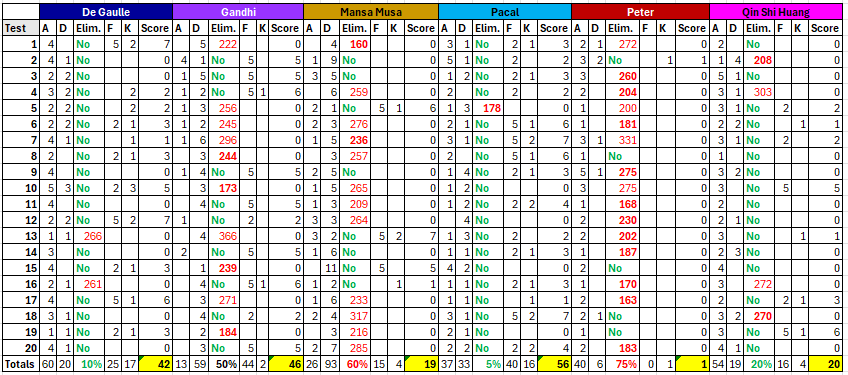

I mean, seriously. What?!? Gandhi winning the most games by far amidst this hostile field and with Mansa Musa as his only ally? Mansa looking like a massive disappointment here? De Gaulle being the 3rd best leader in this setup? Five Diplomatic finishes, all from the same two leaders? Minimal strong teching performances despite this star studded cast? The Actual Game turning out to be atypical? What the heck happened here?

Map Dynamics

This was not your typical 2v4 Good vs. Evil showdown. For starters, most of these leaders had builder-oriented personalities, and although they fought early and often, their overall approaches to these games were centered around internal development rather than external conquest. The only true warmonger in this field was Peter, and the results made it pretty clear that he was the odd man out here. The first tsar was a major wildcard in these games despite, or perhaps because of, his pathetic showing. Sometimes, he did his job softening up the high peaceweight duo for his fellow low peaceweights. Other times, he was so incompetent that he became a free source of territory for his evil brethren. Most of the time, however, Peter was a troll, launching meaningless and distracting wars against his supposed allies that only served to buy more precious time for the Mansa/Gandhi duo, helping them combine to win eleven games despite their awful diplomatic situation.

Of course, it did not hurt that Team Good was comprised of the best economic leader and the best pure culture-monger in Civilization IV, and the two also happened to have the best land. Mansa's land was rich and fertile, while Gandhi had a lot of room and was all but guaranteed a nice peninsula to his east that secured him 3-4 extra cities than normal. Shockingly, it was Gandhi who got the king’s ransom of the win-share. Thankfully, there is an easy explanation: Mansa’s central position, while lush, was a deathtrap in this field, giving all four of the bad guys easy access to him. In many games, Mansa would be so embroiled in war that all he could do was serve as a meat shield for the Indians. As Gandhi’s eight wins can attest, Mansa was a fantastic meat shield, but it came at a cost nonetheless: Mansa only won three games and was either dead or utterly broken in most of the other games. We do not often see Mansa lucky to win the Actual Game!

Interestingly, the biggest hurdles to high peaceweight success were Mansa and Gandhi themselves. The two frequently held different faiths, sparking conflicts between the two that derailed multiple of their games. Alternatively, the two could neglect their militaries and become easy pickings for the four vultures.

Leader Dynamics

These games had three storylines that determined how they went. First, there was Peter and Pacal. Pacal was playing this game on easy mode, as he was almost guaranteed a spot in the Championship Game due to his neighbor Peter’s incompetence and insanity. Peter was like Pacal’s little brother throwing a tantrum at the family board game, basically rage quitting and suiciding into the Mayans once he realized how irrelevant he was. Peter’s culture was also terrible, and there were some games where the Mayans were looking quite weak until Peter gifted them culturally crushed cities to immediately vault Pacal from straggler to game leader. Conversely, there were a couple of scenarios where Peter succeeded in becoming bane of Pacal’s presence. For example, in Game 5 Peter was the one to instigate an early 4v1 that led to Pacal’s one First To Die (his only elimination in the entire set):

Now you know how it feels!

Pacal generally had to kill Peter somewhat early to have a chance at winning. If he failed to do so, either someone else would to become the game leader, or Pacal would be too slow to stop Gandhi.

The next storyline involved the deep enmity between De Gaulle and Mansa. These two fought in every single game, usually to the death. De Gaulle tended to get the better of these conflicts for a couple of reasons. First, Mansa was THE dogpile magnet, and there were many instances where Mansa’s army was all the way in, say, China, while De Gaulle had a fresh army about to break through the Mali borders:

There is an imposter among us here…

Secondly, De Gaulle’s land had a TON of production, while Mansa’s land was on the flatter side, which helped the French overrun Mansa even when technologically behind:

That’s enough hammers to give one Gaullestones

It was almost always a De Gaulle invasion that broke Mansa’s back, opening the floodgates. Upon killing Mansa, De Gaulle’s success hinged on if he could take out Gandhi early enough, if Gandhi was already too far ahead to be stopped, and then if he was large enough to tag team with Qin (more on that later). Mansa would only come out on top if he had an unusually strong opening, if De Gaulle had an unusually weak one, or if De Gaulle attacked Mansa too late for his massive numbers to overcome Mansa’s tech disparity. Less commonly, De Gaulle merely served to soften up Mansa for Pacal to take the spoils instead, a major factor in Pacal's best games.

Finally, there was the Qin v Gandhi conflict, one that often determined if the others even mattered. Qin and Gandhi’s rivalry began long before the first war horns blared out announcing their conflict, as they competed for the same expansions, particularly in the eastern peninsula. Gandhi usually won this race, as Qin's expansion was hampered by his isolated coastal start and his penchant to go after early wonders (amusingly, Qin built The Great Wall in all twenty games). In the rare instances where Qin outexpanded Gandhi, it was a disaster for Team Good. Like De Gaulle and Mansa, Gandhi and Qin fought in virtually every game, although Qin was a slightly more forgiving opponent than De Gaulle. If Gandhi was able to stalemate (or outright win), then his victory was all but assured.

How Typical Was the Actual Game?

4/10. In most games, Mansa's diplomatic situation was too much for him to overcome. A more typical game would see Pacal kill Peter, followed by the three remaining evil leaders to continuously deal hit-and-runs to Mansa until he collapsed or became permanently crippled. From there, two scenarios could take place: either the evil coalition took Gandhi down, with the victor generally being the largest leader no matter who the tech leader was (as we will soon discover), or Gandhi was just too far ahead to be stopped.

The three Mansa Musa victories were each unique in their own way, suggesting that any deviation from the script would likely tip the scales in favor of the Mali. In the livestream, Mansa and Pacal became religious allies (the two were mortal enemies in the AHs), giving Mansa a vital diplomatic shield while turning Gandhi into the dogpile magnet instead. Regarding his Alternate Histories wins: in Game 5, Mansa was by far the biggest beneficiary of the 4v1 of Pacal, while his Game 13 win was a strange game where everyone generally played poorly and Mansa just kind of won by default after conquering Russia. Meanwhile, his Game 15 win was the single most spectacular performance I have, and will have, ever witnessed by a leader in Civilization IV: he somehow mustered a victory despite getting attacked an unfathomable ELEVEN TIMES.

An Addendum: Diplomatic Victories

Diplomatic finishes generally stem from two scenarios:

However, with the exception of Game 12 where Gandhi was legitimately shafted out of a win (although it was partially his fault for beelining Mass Media before Rifling ), every game with a UN finish saw the most deserving winner come up on top. De Gaulle and Qin are not the types of leaders who can just sit back and coast on Financial like Pacal. They had to go out and earn every scrap for themselves, without being born on third base, and while Pacal arrogantly sat back thinking that his Financial trait and a weak Peter suiciding into him was enough to win, De Gaulle and Qin put in all of the hard work taking down Mansa and/or Gandhi. They may have been too far behind in tech to win in any other way, but they still played the best and tried the hardest, and I could not conceive of any Diplomatic finish as a troll ending save for Game 12.

), every game with a UN finish saw the most deserving winner come up on top. De Gaulle and Qin are not the types of leaders who can just sit back and coast on Financial like Pacal. They had to go out and earn every scrap for themselves, without being born on third base, and while Pacal arrogantly sat back thinking that his Financial trait and a weak Peter suiciding into him was enough to win, De Gaulle and Qin put in all of the hard work taking down Mansa and/or Gandhi. They may have been too far behind in tech to win in any other way, but they still played the best and tried the hardest, and I could not conceive of any Diplomatic finish as a troll ending save for Game 12.

Religion had a minimal impact on diplomacy, as in most cases the Evil leaders all followed the same faith. If anything, religion was the primary source of division for Team Good. This was a violent world filled with stalemated wars which considerably down the tech pace despite this field of elite techers. Mansa’s economy was especially mediocre by his lofty standards, although his nearly 5.5 wars per game average had something to do with that. With Gandhi and Mansa winning eleven games, it was no wonder that Cultural finishes dominated, but I still found it crazy that there were as many Diplomatic finishes as Spaceship and Domination combined.

Onto the leader summaries:

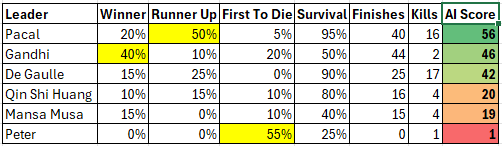

Pacal II of the Maya

Offensive Wars: 37

Defensive Wars: 33

Survival Rate: 95%

Finishes: 4 Wins, 10 Runner Ups (40 Points)

Kills: 16

Overall Score: 56

I thought this would be a Pacal romp, with a few Mansa or Gandhi wins sprinkled here and there and the occasional random De Gaulle or Qin victory. However, this was only a romp as far as Runner Up finishes were concerned. Regarding actually winning, Pacal had to overcome three hurdles:

Ultimately, the Mayan leader did little to dispel the notion that he is an otherwise mediocre leader blessed with a golden package. His overall inactivity cost him dearly in many cases and was the catalyst for the UN dynamics of this set. Those Diplomatic victories would not have taken place had Pacal not placed himself in the awkward circumstance of having a small empire yet also being the tech runaway. As a result, when he inevitably reached Mass Media first and built the UN, the election would be between him and a leader like De Gaulle with, say, 35-40% of the world population, while there was a third party, say Qin, with around 25-30% of the world population who thus held the kingmaking power. If Qin liked De Gaulle more, then De Gaulle could easily snatch a victory from right under Pacal’s nose.

All of this was avoidable if Pacal was able to muster any sort of military initiative. Yes, he had 16 kills, but a good chunk of those came from Peter having drank too much vodka before these games. Naturally, Pacal’s four wins came when he got his hands dirty and conquered some fools. Pacal is one of the game's very best economic leaders, but this set demonstrated why he does not quite belong in the absolute top tier of leaders. For a Financial leader with one of the best packages in the game, a dream diplomatic setup, and two easy neighbors to kill, Pacal should have performed far better than 56 points and four wins. There is a reason why he is a leader that we root against in every game.

Best Performance: Game 6 demonstrated Pacal’s sky high ceiling, as he actually leveraged his economic advantage to murder the rest of his competition.

Worst Performance: I can give a pass to his one death – there is nothing anyone can do about an early 4v1. More embarrassing was his Game 12, where Pacal failed to connect metals and was rendered irrelevant by an early Peter attack.

Hare Award: Pacal would have easily won Game 11 had he not taken a nap with his Mechs and Modern Armors and allowed a backwards Gandhi to win by Culture.

Democratic People’s Republic Of Wang Kon Award: De Gaulle was for once the tech runaway in Game 10… but Pacal baited the French into attacking him and devoting his entire production to military rather than research, allowing Qin to catch up in tech (with some help from the Internet). Then, when De Gaulle was about to run over Pacal, the Mayans used the UN to end De Gaulle’s conquest, keeping it in Mayan hands. De Gaulle then voted Qin as world leader on the same turn he launched his spaceship, and Pacal had completed a successful troll.

Gandhi of India

Offensive Wars: 13

Defensive Wars: 59

Survival Rate: 50%

Finishes: 8 Wins, 2 Runner Ups (44 Points)

Kills: 2

Overall Score: 46

For once, Gandhi was not a lamb to the slaughter in a playoff game! On the contrary, Gandhi was the map’s best performer, even if the score does not indicate this. To start, Mansa Musa should never have to pay for his drinks in Delhi ever again. Mansa had Skirmishers to shelter Team Good from early dogpiles, and his economic skills kept his tech going despite being mired in an endless brutal struggle for survival. Mansa’s resilience was instrumental in giving Gandhi those precious few extra turns that meant the difference between victory and destruction. Put literally any other leader in that central spot, and Gandhi would likely have been dead meat in this setup.

This is not to say Gandhi did not deserve his success. He executed his part of the bargain to near perfection and proved actually capable of defending himself if need be (unlike in the livestream). Normally, being in culture mode from Turn 0 is a weakness, but here, every turn mattered for Gandhi. Game 20, for example, saw Gandhi get three legendary cities just as Tanks from the Sino-French coalition army were outside of his 3rd city – one more turn, and Gandhi was done for. I noticed some utterly absurd cultural beelines: getting Meditation AND Polytheism, going for Philosophy before getting the crucial defensive Longbows, and which I had already mentioned, going for MASS MEDIA before RIFLING, a move that directly threw away a victory in Game 12. Despite this extreme display of culturephilia, Gandhi’s teching was excellent (perhaps aided by his strong expansion), and he was more than capable of helping with military matters; he was a better fighter than his 13 offensive wars may have suggested.

Unsurprisingly, Gandhi either won, almost won (In addition to Game 12, Gandhi’s Game 18 Runner Up finish came when he uncharacteristically never touched the cultural slider when he would have won otherwise), or died. There were three reasons Gandhi could falter. First, he and Mansa could come to blows due to religious differences, leaving him completely isolated and a sitting duck. This was not necessarily a death knell for Gandhi’s chances, as there were two games where the two fought and Gandhi still won, one of them being the oddball Game 2 where Indira took the helm (Gandhi actually attacked early in that game). Nevertheless, fighting his only ally was not good for his prospects. Second, Mansa could fall apart too quickly, meaning that Gandhi was next on the chopping block – this was the most common cause of Gandhi’s failures. Finally, Gandhi could be his own worst enemy at times. He was prone to crashing his economy if he combined over-expansion with the neglection of essential development techs like Wheel and Pottery (Game 13). I noticed Gandhi quite effectively utilized a failgold economy (for those unfamiliar, this means to use gold from incomplete wonder builds to fuel research – a common technique on higher difficulties) in these games, but sometimes that was not enough and he fell too far behind to compete. Gandhi could also fail to properly defend himself, like in Game 15 where he died to a cross-map invasion from De Gaulle; this was how he failed in the Actual Game. Nonetheless, this set showed why Gandhi is an elite culture-monger, and I kind of wish that we saw this Gandhi in the livestream game.

Best Performance: Game 14 was a well-executed Cultural victory, especially coming from a non-Financial leader.

Worst Performance: Crashing his economy in Game 13, failing to expand, and dying one turn before Mansa’s victory triggered. Dishonorable mention to Game 15, for reasons already mentioned.

Tortoise Award: With some help from Pacal’s inactivity, Gandhi won a Culture victory in Game 11 without ever turning up the Culture slider.

No More Mr. Nice Guy Award: Look at his Game 2 statline! At first glance, his zero kills may have made one think that Gandhi should stick to his pacifist ways, but he should have had at least two kills in that game. His first one was stolen when Peter troll sniped Qin in a last-minute vulture of a dying civ, and Gandhi was in the process of running over De Gaulle and Peter at the same time when he hit three legendary cities.

Why You Should Never Give The Nice Guy A Chance Award:

De Gaulle of France

Offensive Wars: 60

Defensive Wars: 20

Survival Rate: 90%

Finishes: 3 Wins, 5 Runner Ups (25 Points)

Kills: 17

Overall Score: 42

Qin Shi Huang of China

Offensive Wars: 54

Defensive Wars: 19

Survival Rate: 80%

Finishes: 2 Wins, 3 Runner Ups (16 Points)

Kills: 4

Overall Score: 20

Although there was a decent score disparity between these two leaders, I chose to pair them here as they were for all intents and purposes on the same team. Even outside of map dynamics, these two leaders share many similarities. Both leaders have excellent starting techs and like-minded personalities, both being Industrious low peaceweight backstabbers who prefer more builder-focused strategies. Qin has the blah Protective while De Gaulle has the decent Charismatic as a second trait, but Qin compensates with better uniques. Regarding the map, both leaders had Fishing starts and at least one dogpile candidate as a neighbor. These two were not strange bedfellows in these replays – despite being conniving backstabbers situated on the opposite corners of the map, their objectives and pathways to victory were in perfect tandem with each other. All of their wins followed the exact same pattern – run over one or more of their neighbors, wait for Pacal or Gandhi to build the UN, and then rig the UN in their favor. Yet another sign of how similar the two were: they had virtually identical offensive to defensive war ratios of 3:1. At the very least, one leader could get into the championship game by killing one of their neighbors and leveraging that into a Runner Up finish. Their strategies reminded me of a human Deity player – they tended to break out with Cuirassiers (De Gaulle’s two move Musketeers were quite useful with this), before splitting enough territory to win through the UN. Their failures stemmed from the following: taking too long to conquer, being unable to coordinate dogpiles, and eventually getting wrecked in the late game by a much more advanced enemy.

The main reason why De Gaulle’s score was so much better: his land and neighbor situation. While Qin had to contend with Pacal and the hyper-cultural Gandhi as neighbors (and was First To Die a couple of times as a result), De Gaulle had the hapless Peter and the more vulnerable Mansa, the latter of whom was a more consistent dogpile magnet than Gandhi. Moreover, De Gaulle’s land was just better both from a quality and quantity perspective. Qin either needed to conquer Gandhi in due time or effectively use a Great Lighthouse-Colossus economy in order to have a chance. Switch Qin and De Gaulle’s starting positions, and their results would likely be flip-flopped. Altogether, this was a better performance from the two than I was expecting, and perhaps the community especially underestimates De Gaulle. The French leader has flailed around more often than not, but this season did demonstrate that he can be a viable leader.

Best Performances: Games 1 and 10, respectively, as those were the games where the two would have had a chance to win without the UN.

Worst Performances: De Gaulle’s expansion was moribund in both the games he died, and Qin tried to backstab Pacal in Game 18, only for it to completely backfire in his face. Qin also got run over by GANDHI in Game 2.

Civil Disobedience Award: In Game 14, De Gaulle (and Pacal, and the United Nations) were about to finish off Mansa… when his last city became ensconced in Gandhi’s borders. Since Gandhi refused to sign Open Borders, De Gaulle was stuck in a forever war with another opponent, which gave the Indians all the security they needed.

City Wok Award:

Gotta keep out those darn 北京人.

Mansa Musa of Mali

Offensive Wars: 26

Defensive Wars: 93

Survival Rate: 40%

Finishes: 3 Wins, 0 Runner Ups (15 Points)

Kills: 4

Overall Score: 19

Poor, poor Mansa. 93 defensive wars says it all. His games were painful to watch, as the Malinese leader would frequently explode out into what appeared to be a dominant position, until the first of a relentless barrage of attacks took place, taking down the titan through death by a thousand cuts. In every game, Mansa was teetering on the knife’s edge, never sure if the latest invasion would cause the whole moneybags machine to collapse. Even if he withstood these invasions, he was more often than not a husk of himself, failing to advance in more than half of the games he survived.

With that said, it was still clear why Mansa is one of the best leaders in AI Survivor. I am unsure that any other leader is capable of winning 3/20 games while being attacked 93 times. In fact, they would be lucky to win one game. Mansa only had one easy game, that being Game 5 where Pacal uncharacteristically died early. In the other 19 games, Mansa had one major issue: this was not the right field for culture-monging, not in this hostile field and especially not with Gandhi in the game. Mansa could have done better had he played more like he did in his opening round game, rather than trying to build missionaries while being in a 3v1 and still missing out on the cultural milestones. When Mansa did exhibit aggression, it was not always smart – he attacked Gandhi more often than I thought he would, and taking out his only potential ally tended to backfire on him. At the end of the day, Mansa’s central position proved to be a deathtrap, and he was incredibly lucky to have befriended Pacal in the real game to secure a Championship Game spot.

Best Performance: In Game 15, when he faced 11 invasions, Mansa had to contend with a 3v1 on five separate occasions. Also:

Worst Performance: Game 1 was perhaps the one game where Mansa looked extremely pedestrian, and was deservedly First To Die.

Living Long Enough To Become The Villain Award:

Peter of Russia

Offensive Wars: 40

Defensive Wars: 6

Survival Rate: 25%

Finishes: 0 Wins, 0 Runner Ups (0 Points)

Kills: 1

Overall Score: 1

I have read Alternate Histories sets where leaders scored zero points, where leaders died in all twenty games, and where leaders squandered starting positions that would make a human Deity player jump in joy. Yet, there is a valid argument that this may be the single worst Alternate Histories performance ever. To start, look at the war counter. Peter was attacked only six times - I do not think I have ever seen a defensive war count that low - yet he died in three quarters of the replays, was the overwhelming favorite for First To Die despite being in the peaceweight majority, never sniffed a top two spot, and would have laid a complete egg had he not somehow sniped what should have been Gandhi’s kill in Game 2. This was an utterly inexcusable performance for a warmonger with a dream diplomatic setup and golden dogpile opportunities.

There were two major problems with Peter here. First, in this field, he might as well have been Ragnar or Genghis Khan, as he was the only pure warmonger and by far the worst economic leader in this field. Most games saw him launch random attacks without rhyme or reason (often with only 5-6 cities), get absorbed by one of his neighbors, or derail the evil gameplan with troll war declarations. The second issue, and perhaps a mitigating factor here: Peter had BY FAR the worst land. He had a coastal capital without coastal resources, little room to expand (exacerbated by his poor cultural output), and lots of jungle with land that was not good enough to compensate post-Iron Working. His land was so bad (especially relative to his rivals), I think Huayna Capac would have struggled in his position. With that said, although there is some debate over if Peter is an underestimated or overrated leader due to him sometimes overperforming in other Alternate Histories sets, I personally see him perfectly rated as a mediocrity.

Best Performance: Surely, you must be joking…

Worst Performance: Game 1, where his expansion was so awful that De Gaulle was able to jam border cities right next to Moscow.

Temujin Award:

Yes, Peter now has just three cities on T73.

Conclusions

This was yet another fascinating set, full of twists and turns, some shocking results, and some of the most exciting individual games I had the pleasure of watching. Some people enjoy seeing pure dominance, while others like to see evenly matched Alternate History sets – and I have personally find my favorite sets to be the ones with clashes to the death between Good and Evil, like in both this and the first playoff game. Some final food for thought: maybe we underestimate high peaceweights a little bit? This was not the first set in this season where the high peaceweights were able to overcome long odds to find success. Do not be surprised when the goodie two shoes of Civ IV eventually get their time to shine.

Probably the most shocking result I have ever gotten. This remains and will probably remain my all time favorite set ever.

Overview

To use my best Sullla voice: Whaaaaaaaaaaaaaaat?!?!?!

I mean, seriously. What?!? Gandhi winning the most games by far amidst this hostile field and with Mansa Musa as his only ally? Mansa looking like a massive disappointment here? De Gaulle being the 3rd best leader in this setup? Five Diplomatic finishes, all from the same two leaders? Minimal strong teching performances despite this star studded cast? The Actual Game turning out to be atypical? What the heck happened here?

Map Dynamics

This was not your typical 2v4 Good vs. Evil showdown. For starters, most of these leaders had builder-oriented personalities, and although they fought early and often, their overall approaches to these games were centered around internal development rather than external conquest. The only true warmonger in this field was Peter, and the results made it pretty clear that he was the odd man out here. The first tsar was a major wildcard in these games despite, or perhaps because of, his pathetic showing. Sometimes, he did his job softening up the high peaceweight duo for his fellow low peaceweights. Other times, he was so incompetent that he became a free source of territory for his evil brethren. Most of the time, however, Peter was a troll, launching meaningless and distracting wars against his supposed allies that only served to buy more precious time for the Mansa/Gandhi duo, helping them combine to win eleven games despite their awful diplomatic situation.

Of course, it did not hurt that Team Good was comprised of the best economic leader and the best pure culture-monger in Civilization IV, and the two also happened to have the best land. Mansa's land was rich and fertile, while Gandhi had a lot of room and was all but guaranteed a nice peninsula to his east that secured him 3-4 extra cities than normal. Shockingly, it was Gandhi who got the king’s ransom of the win-share. Thankfully, there is an easy explanation: Mansa’s central position, while lush, was a deathtrap in this field, giving all four of the bad guys easy access to him. In many games, Mansa would be so embroiled in war that all he could do was serve as a meat shield for the Indians. As Gandhi’s eight wins can attest, Mansa was a fantastic meat shield, but it came at a cost nonetheless: Mansa only won three games and was either dead or utterly broken in most of the other games. We do not often see Mansa lucky to win the Actual Game!

Interestingly, the biggest hurdles to high peaceweight success were Mansa and Gandhi themselves. The two frequently held different faiths, sparking conflicts between the two that derailed multiple of their games. Alternatively, the two could neglect their militaries and become easy pickings for the four vultures.

Leader Dynamics

These games had three storylines that determined how they went. First, there was Peter and Pacal. Pacal was playing this game on easy mode, as he was almost guaranteed a spot in the Championship Game due to his neighbor Peter’s incompetence and insanity. Peter was like Pacal’s little brother throwing a tantrum at the family board game, basically rage quitting and suiciding into the Mayans once he realized how irrelevant he was. Peter’s culture was also terrible, and there were some games where the Mayans were looking quite weak until Peter gifted them culturally crushed cities to immediately vault Pacal from straggler to game leader. Conversely, there were a couple of scenarios where Peter succeeded in becoming bane of Pacal’s presence. For example, in Game 5 Peter was the one to instigate an early 4v1 that led to Pacal’s one First To Die (his only elimination in the entire set):

Now you know how it feels!

Pacal generally had to kill Peter somewhat early to have a chance at winning. If he failed to do so, either someone else would to become the game leader, or Pacal would be too slow to stop Gandhi.

The next storyline involved the deep enmity between De Gaulle and Mansa. These two fought in every single game, usually to the death. De Gaulle tended to get the better of these conflicts for a couple of reasons. First, Mansa was THE dogpile magnet, and there were many instances where Mansa’s army was all the way in, say, China, while De Gaulle had a fresh army about to break through the Mali borders:

There is an imposter among us here…

Secondly, De Gaulle’s land had a TON of production, while Mansa’s land was on the flatter side, which helped the French overrun Mansa even when technologically behind:

That’s enough hammers to give one Gaullestones

It was almost always a De Gaulle invasion that broke Mansa’s back, opening the floodgates. Upon killing Mansa, De Gaulle’s success hinged on if he could take out Gandhi early enough, if Gandhi was already too far ahead to be stopped, and then if he was large enough to tag team with Qin (more on that later). Mansa would only come out on top if he had an unusually strong opening, if De Gaulle had an unusually weak one, or if De Gaulle attacked Mansa too late for his massive numbers to overcome Mansa’s tech disparity. Less commonly, De Gaulle merely served to soften up Mansa for Pacal to take the spoils instead, a major factor in Pacal's best games.

Finally, there was the Qin v Gandhi conflict, one that often determined if the others even mattered. Qin and Gandhi’s rivalry began long before the first war horns blared out announcing their conflict, as they competed for the same expansions, particularly in the eastern peninsula. Gandhi usually won this race, as Qin's expansion was hampered by his isolated coastal start and his penchant to go after early wonders (amusingly, Qin built The Great Wall in all twenty games). In the rare instances where Qin outexpanded Gandhi, it was a disaster for Team Good. Like De Gaulle and Mansa, Gandhi and Qin fought in virtually every game, although Qin was a slightly more forgiving opponent than De Gaulle. If Gandhi was able to stalemate (or outright win), then his victory was all but assured.

How Typical Was the Actual Game?

4/10. In most games, Mansa's diplomatic situation was too much for him to overcome. A more typical game would see Pacal kill Peter, followed by the three remaining evil leaders to continuously deal hit-and-runs to Mansa until he collapsed or became permanently crippled. From there, two scenarios could take place: either the evil coalition took Gandhi down, with the victor generally being the largest leader no matter who the tech leader was (as we will soon discover), or Gandhi was just too far ahead to be stopped.

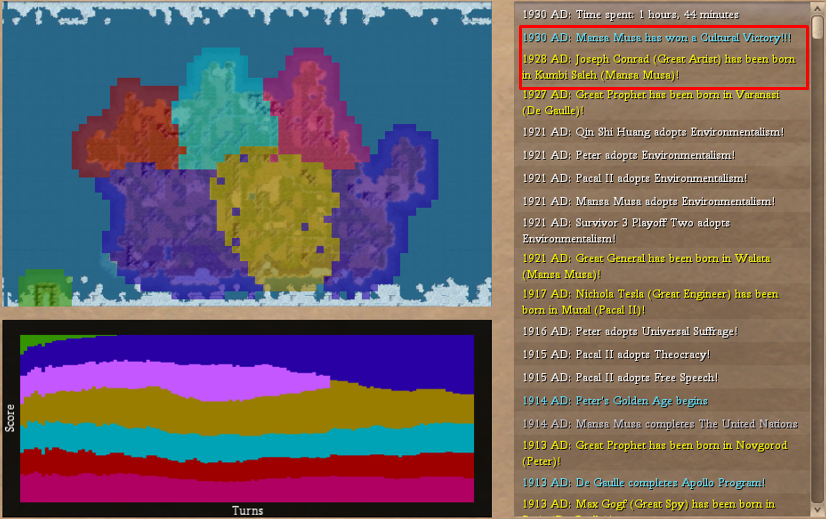

The three Mansa Musa victories were each unique in their own way, suggesting that any deviation from the script would likely tip the scales in favor of the Mali. In the livestream, Mansa and Pacal became religious allies (the two were mortal enemies in the AHs), giving Mansa a vital diplomatic shield while turning Gandhi into the dogpile magnet instead. Regarding his Alternate Histories wins: in Game 5, Mansa was by far the biggest beneficiary of the 4v1 of Pacal, while his Game 13 win was a strange game where everyone generally played poorly and Mansa just kind of won by default after conquering Russia. Meanwhile, his Game 15 win was the single most spectacular performance I have, and will have, ever witnessed by a leader in Civilization IV: he somehow mustered a victory despite getting attacked an unfathomable ELEVEN TIMES.

An Addendum: Diplomatic Victories

Diplomatic finishes generally stem from two scenarios:

- Coronating the obvious game winner 30 or so turns before that leader would have won anyway – this is the most common scenario.

- The infamous “troll” diplo where a much less deserving leader wins because he for whatever reason had better diplomacy with the non-ballot leaders while the non-ballot leaders were relevant enough to play kingmaker – we always remember these cases, but they occur far less frequently than we think.

However, with the exception of Game 12 where Gandhi was legitimately shafted out of a win (although it was partially his fault for beelining Mass Media before Rifling

), every game with a UN finish saw the most deserving winner come up on top. De Gaulle and Qin are not the types of leaders who can just sit back and coast on Financial like Pacal. They had to go out and earn every scrap for themselves, without being born on third base, and while Pacal arrogantly sat back thinking that his Financial trait and a weak Peter suiciding into him was enough to win, De Gaulle and Qin put in all of the hard work taking down Mansa and/or Gandhi. They may have been too far behind in tech to win in any other way, but they still played the best and tried the hardest, and I could not conceive of any Diplomatic finish as a troll ending save for Game 12.

), every game with a UN finish saw the most deserving winner come up on top. De Gaulle and Qin are not the types of leaders who can just sit back and coast on Financial like Pacal. They had to go out and earn every scrap for themselves, without being born on third base, and while Pacal arrogantly sat back thinking that his Financial trait and a weak Peter suiciding into him was enough to win, De Gaulle and Qin put in all of the hard work taking down Mansa and/or Gandhi. They may have been too far behind in tech to win in any other way, but they still played the best and tried the hardest, and I could not conceive of any Diplomatic finish as a troll ending save for Game 12.Religion had a minimal impact on diplomacy, as in most cases the Evil leaders all followed the same faith. If anything, religion was the primary source of division for Team Good. This was a violent world filled with stalemated wars which considerably down the tech pace despite this field of elite techers. Mansa’s economy was especially mediocre by his lofty standards, although his nearly 5.5 wars per game average had something to do with that. With Gandhi and Mansa winning eleven games, it was no wonder that Cultural finishes dominated, but I still found it crazy that there were as many Diplomatic finishes as Spaceship and Domination combined.

Onto the leader summaries:

Pacal II of the Maya

Offensive Wars: 37

Defensive Wars: 33

Survival Rate: 95%

Finishes: 4 Wins, 10 Runner Ups (40 Points)

Kills: 16

Overall Score: 56

I thought this would be a Pacal romp, with a few Mansa or Gandhi wins sprinkled here and there and the occasional random De Gaulle or Qin victory. However, this was only a romp as far as Runner Up finishes were concerned. Regarding actually winning, Pacal had to overcome three hurdles:

- Gandhi having a Gandhi game and winning

- Mansa having a Mansa game and winning

- De Gaulle or Qin getting large, building camaraderie, and then using the United Nations to pull the rug underneath Pacal.

Ultimately, the Mayan leader did little to dispel the notion that he is an otherwise mediocre leader blessed with a golden package. His overall inactivity cost him dearly in many cases and was the catalyst for the UN dynamics of this set. Those Diplomatic victories would not have taken place had Pacal not placed himself in the awkward circumstance of having a small empire yet also being the tech runaway. As a result, when he inevitably reached Mass Media first and built the UN, the election would be between him and a leader like De Gaulle with, say, 35-40% of the world population, while there was a third party, say Qin, with around 25-30% of the world population who thus held the kingmaking power. If Qin liked De Gaulle more, then De Gaulle could easily snatch a victory from right under Pacal’s nose.

All of this was avoidable if Pacal was able to muster any sort of military initiative. Yes, he had 16 kills, but a good chunk of those came from Peter having drank too much vodka before these games. Naturally, Pacal’s four wins came when he got his hands dirty and conquered some fools. Pacal is one of the game's very best economic leaders, but this set demonstrated why he does not quite belong in the absolute top tier of leaders. For a Financial leader with one of the best packages in the game, a dream diplomatic setup, and two easy neighbors to kill, Pacal should have performed far better than 56 points and four wins. There is a reason why he is a leader that we root against in every game.

Best Performance: Game 6 demonstrated Pacal’s sky high ceiling, as he actually leveraged his economic advantage to murder the rest of his competition.

Worst Performance: I can give a pass to his one death – there is nothing anyone can do about an early 4v1. More embarrassing was his Game 12, where Pacal failed to connect metals and was rendered irrelevant by an early Peter attack.

Hare Award: Pacal would have easily won Game 11 had he not taken a nap with his Mechs and Modern Armors and allowed a backwards Gandhi to win by Culture.

Democratic People’s Republic Of Wang Kon Award: De Gaulle was for once the tech runaway in Game 10… but Pacal baited the French into attacking him and devoting his entire production to military rather than research, allowing Qin to catch up in tech (with some help from the Internet). Then, when De Gaulle was about to run over Pacal, the Mayans used the UN to end De Gaulle’s conquest, keeping it in Mayan hands. De Gaulle then voted Qin as world leader on the same turn he launched his spaceship, and Pacal had completed a successful troll.

Gandhi of India

Offensive Wars: 13

Defensive Wars: 59

Survival Rate: 50%

Finishes: 8 Wins, 2 Runner Ups (44 Points)

Kills: 2

Overall Score: 46

For once, Gandhi was not a lamb to the slaughter in a playoff game! On the contrary, Gandhi was the map’s best performer, even if the score does not indicate this. To start, Mansa Musa should never have to pay for his drinks in Delhi ever again. Mansa had Skirmishers to shelter Team Good from early dogpiles, and his economic skills kept his tech going despite being mired in an endless brutal struggle for survival. Mansa’s resilience was instrumental in giving Gandhi those precious few extra turns that meant the difference between victory and destruction. Put literally any other leader in that central spot, and Gandhi would likely have been dead meat in this setup.

This is not to say Gandhi did not deserve his success. He executed his part of the bargain to near perfection and proved actually capable of defending himself if need be (unlike in the livestream). Normally, being in culture mode from Turn 0 is a weakness, but here, every turn mattered for Gandhi. Game 20, for example, saw Gandhi get three legendary cities just as Tanks from the Sino-French coalition army were outside of his 3rd city – one more turn, and Gandhi was done for. I noticed some utterly absurd cultural beelines: getting Meditation AND Polytheism, going for Philosophy before getting the crucial defensive Longbows, and which I had already mentioned, going for MASS MEDIA before RIFLING, a move that directly threw away a victory in Game 12. Despite this extreme display of culturephilia, Gandhi’s teching was excellent (perhaps aided by his strong expansion), and he was more than capable of helping with military matters; he was a better fighter than his 13 offensive wars may have suggested.

Unsurprisingly, Gandhi either won, almost won (In addition to Game 12, Gandhi’s Game 18 Runner Up finish came when he uncharacteristically never touched the cultural slider when he would have won otherwise), or died. There were three reasons Gandhi could falter. First, he and Mansa could come to blows due to religious differences, leaving him completely isolated and a sitting duck. This was not necessarily a death knell for Gandhi’s chances, as there were two games where the two fought and Gandhi still won, one of them being the oddball Game 2 where Indira took the helm (Gandhi actually attacked early in that game). Nevertheless, fighting his only ally was not good for his prospects. Second, Mansa could fall apart too quickly, meaning that Gandhi was next on the chopping block – this was the most common cause of Gandhi’s failures. Finally, Gandhi could be his own worst enemy at times. He was prone to crashing his economy if he combined over-expansion with the neglection of essential development techs like Wheel and Pottery (Game 13). I noticed Gandhi quite effectively utilized a failgold economy (for those unfamiliar, this means to use gold from incomplete wonder builds to fuel research – a common technique on higher difficulties) in these games, but sometimes that was not enough and he fell too far behind to compete. Gandhi could also fail to properly defend himself, like in Game 15 where he died to a cross-map invasion from De Gaulle; this was how he failed in the Actual Game. Nonetheless, this set showed why Gandhi is an elite culture-monger, and I kind of wish that we saw this Gandhi in the livestream game.

Best Performance: Game 14 was a well-executed Cultural victory, especially coming from a non-Financial leader.

Worst Performance: Crashing his economy in Game 13, failing to expand, and dying one turn before Mansa’s victory triggered. Dishonorable mention to Game 15, for reasons already mentioned.

Tortoise Award: With some help from Pacal’s inactivity, Gandhi won a Culture victory in Game 11 without ever turning up the Culture slider.

No More Mr. Nice Guy Award: Look at his Game 2 statline! At first glance, his zero kills may have made one think that Gandhi should stick to his pacifist ways, but he should have had at least two kills in that game. His first one was stolen when Peter troll sniped Qin in a last-minute vulture of a dying civ, and Gandhi was in the process of running over De Gaulle and Peter at the same time when he hit three legendary cities.

Why You Should Never Give The Nice Guy A Chance Award:

De Gaulle of France

Offensive Wars: 60

Defensive Wars: 20

Survival Rate: 90%

Finishes: 3 Wins, 5 Runner Ups (25 Points)

Kills: 17

Overall Score: 42

Qin Shi Huang of China

Offensive Wars: 54

Defensive Wars: 19

Survival Rate: 80%

Finishes: 2 Wins, 3 Runner Ups (16 Points)

Kills: 4

Overall Score: 20

Although there was a decent score disparity between these two leaders, I chose to pair them here as they were for all intents and purposes on the same team. Even outside of map dynamics, these two leaders share many similarities. Both leaders have excellent starting techs and like-minded personalities, both being Industrious low peaceweight backstabbers who prefer more builder-focused strategies. Qin has the blah Protective while De Gaulle has the decent Charismatic as a second trait, but Qin compensates with better uniques. Regarding the map, both leaders had Fishing starts and at least one dogpile candidate as a neighbor. These two were not strange bedfellows in these replays – despite being conniving backstabbers situated on the opposite corners of the map, their objectives and pathways to victory were in perfect tandem with each other. All of their wins followed the exact same pattern – run over one or more of their neighbors, wait for Pacal or Gandhi to build the UN, and then rig the UN in their favor. Yet another sign of how similar the two were: they had virtually identical offensive to defensive war ratios of 3:1. At the very least, one leader could get into the championship game by killing one of their neighbors and leveraging that into a Runner Up finish. Their strategies reminded me of a human Deity player – they tended to break out with Cuirassiers (De Gaulle’s two move Musketeers were quite useful with this), before splitting enough territory to win through the UN. Their failures stemmed from the following: taking too long to conquer, being unable to coordinate dogpiles, and eventually getting wrecked in the late game by a much more advanced enemy.

The main reason why De Gaulle’s score was so much better: his land and neighbor situation. While Qin had to contend with Pacal and the hyper-cultural Gandhi as neighbors (and was First To Die a couple of times as a result), De Gaulle had the hapless Peter and the more vulnerable Mansa, the latter of whom was a more consistent dogpile magnet than Gandhi. Moreover, De Gaulle’s land was just better both from a quality and quantity perspective. Qin either needed to conquer Gandhi in due time or effectively use a Great Lighthouse-Colossus economy in order to have a chance. Switch Qin and De Gaulle’s starting positions, and their results would likely be flip-flopped. Altogether, this was a better performance from the two than I was expecting, and perhaps the community especially underestimates De Gaulle. The French leader has flailed around more often than not, but this season did demonstrate that he can be a viable leader.

Best Performances: Games 1 and 10, respectively, as those were the games where the two would have had a chance to win without the UN.

Worst Performances: De Gaulle’s expansion was moribund in both the games he died, and Qin tried to backstab Pacal in Game 18, only for it to completely backfire in his face. Qin also got run over by GANDHI in Game 2.

Civil Disobedience Award: In Game 14, De Gaulle (and Pacal, and the United Nations) were about to finish off Mansa… when his last city became ensconced in Gandhi’s borders. Since Gandhi refused to sign Open Borders, De Gaulle was stuck in a forever war with another opponent, which gave the Indians all the security they needed.

City Wok Award:

Gotta keep out those darn 北京人.

Mansa Musa of Mali

Offensive Wars: 26

Defensive Wars: 93

Survival Rate: 40%

Finishes: 3 Wins, 0 Runner Ups (15 Points)

Kills: 4

Overall Score: 19

Poor, poor Mansa. 93 defensive wars says it all. His games were painful to watch, as the Malinese leader would frequently explode out into what appeared to be a dominant position, until the first of a relentless barrage of attacks took place, taking down the titan through death by a thousand cuts. In every game, Mansa was teetering on the knife’s edge, never sure if the latest invasion would cause the whole moneybags machine to collapse. Even if he withstood these invasions, he was more often than not a husk of himself, failing to advance in more than half of the games he survived.

With that said, it was still clear why Mansa is one of the best leaders in AI Survivor. I am unsure that any other leader is capable of winning 3/20 games while being attacked 93 times. In fact, they would be lucky to win one game. Mansa only had one easy game, that being Game 5 where Pacal uncharacteristically died early. In the other 19 games, Mansa had one major issue: this was not the right field for culture-monging, not in this hostile field and especially not with Gandhi in the game. Mansa could have done better had he played more like he did in his opening round game, rather than trying to build missionaries while being in a 3v1 and still missing out on the cultural milestones. When Mansa did exhibit aggression, it was not always smart – he attacked Gandhi more often than I thought he would, and taking out his only potential ally tended to backfire on him. At the end of the day, Mansa’s central position proved to be a deathtrap, and he was incredibly lucky to have befriended Pacal in the real game to secure a Championship Game spot.

Best Performance: In Game 15, when he faced 11 invasions, Mansa had to contend with a 3v1 on five separate occasions. Also:

Worst Performance: Game 1 was perhaps the one game where Mansa looked extremely pedestrian, and was deservedly First To Die.

Living Long Enough To Become The Villain Award:

Peter of Russia

Offensive Wars: 40

Defensive Wars: 6

Survival Rate: 25%

Finishes: 0 Wins, 0 Runner Ups (0 Points)

Kills: 1

Overall Score: 1

I have read Alternate Histories sets where leaders scored zero points, where leaders died in all twenty games, and where leaders squandered starting positions that would make a human Deity player jump in joy. Yet, there is a valid argument that this may be the single worst Alternate Histories performance ever. To start, look at the war counter. Peter was attacked only six times - I do not think I have ever seen a defensive war count that low - yet he died in three quarters of the replays, was the overwhelming favorite for First To Die despite being in the peaceweight majority, never sniffed a top two spot, and would have laid a complete egg had he not somehow sniped what should have been Gandhi’s kill in Game 2. This was an utterly inexcusable performance for a warmonger with a dream diplomatic setup and golden dogpile opportunities.

There were two major problems with Peter here. First, in this field, he might as well have been Ragnar or Genghis Khan, as he was the only pure warmonger and by far the worst economic leader in this field. Most games saw him launch random attacks without rhyme or reason (often with only 5-6 cities), get absorbed by one of his neighbors, or derail the evil gameplan with troll war declarations. The second issue, and perhaps a mitigating factor here: Peter had BY FAR the worst land. He had a coastal capital without coastal resources, little room to expand (exacerbated by his poor cultural output), and lots of jungle with land that was not good enough to compensate post-Iron Working. His land was so bad (especially relative to his rivals), I think Huayna Capac would have struggled in his position. With that said, although there is some debate over if Peter is an underestimated or overrated leader due to him sometimes overperforming in other Alternate Histories sets, I personally see him perfectly rated as a mediocrity.

Best Performance: Surely, you must be joking…

Worst Performance: Game 1, where his expansion was so awful that De Gaulle was able to jam border cities right next to Moscow.

Temujin Award:

Yes, Peter now has just three cities on T73.

Conclusions

This was yet another fascinating set, full of twists and turns, some shocking results, and some of the most exciting individual games I had the pleasure of watching. Some people enjoy seeing pure dominance, while others like to see evenly matched Alternate History sets – and I have personally find my favorite sets to be the ones with clashes to the death between Good and Evil, like in both this and the first playoff game. Some final food for thought: maybe we underestimate high peaceweights a little bit? This was not the first set in this season where the high peaceweights were able to overcome long odds to find success. Do not be surprised when the goodie two shoes of Civ IV eventually get their time to shine.

Last edited: