You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

stNNES7: Worlds and Empires

- Thread starter North King

- Start date

North King

blech

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2004

- Messages

- 18,165

Jason The King said:When is the deadline today, north?

In the next... oh... 6 hours or something.

North King

blech

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2004

- Messages

- 18,165

Because some people *coughdascough* are being arrogant perks, and because theoretically das gave up the copyright to his idea when he shared it with me about two months before he put it into action, and because I'd like seeing stories which can have actual character development without immortal kings, I'm probably going to switch to an ITNES system soon enough. Say, in the next three turns.

What say ye, NESers?

What say ye, NESers?

Grandmaster

Deity

Fine with me. Orders sent.

Oruc

Reactionary

i dont know, i dont really like anything to do with das

edit: and the fact i have no idea what the Itnes system is

edit: and the fact i have no idea what the Itnes system is

Jason The King

Deity

heh, i dont care for the idea too much. i like the nes too much to have whole periods of times skipped and have no control over my country. i like the boring times of peace when i get to build up my country, i dont play an NES just to fight wars all the time.

conehead234

Braves on the Warpath

Orders sent.

North King

blech

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2004

- Messages

- 18,165

Jason The King said:heh, i dont care for the idea too much. i like the nes too much to have whole periods of times skipped and have no control over my country. i like the boring times of peace when i get to build up my country, i dont play an NES just to fight wars all the time.

I wouldn't do it like das. I would do, say, updates every 200 years or something, until events get too big to handle in that sort of update, and switch to like 5 years or some such.

F*** NO!

this NES is killer the way it is being developed, in the standard NES style; leave the experimental update system for an experimental NES- this NES is successful because it uses the best sytem so far developed, and dosent err from that standard.

this NES is killer the way it is being developed, in the standard NES style; leave the experimental update system for an experimental NES- this NES is successful because it uses the best sytem so far developed, and dosent err from that standard.

North King

blech

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2004

- Messages

- 18,165

I didn't ask you to bleed my eyeballs.

well, you didnt say I couldnt bleed your eyeballs either, so uhhh, next time, uhhh, specify that i cant, in fact belled your eyeballs, or, if I can, to what extent they can be blead (blead to death, blead to half infaltion, and so on) specifics NK, I need specifics!

Grandmaster

Deity

The country along the Senegal River had been annexed many years ago, overrun quickly by the unstoppable Malian army. Attempts had immediately been made to subdue and assimilate this territory; its population had been sold into slavery, and the irrigation system and public works of Mali had been extended into the Senegal valley. Despite these effort, the power and culture of the Malian kingdom were not yet fully secured in the West.

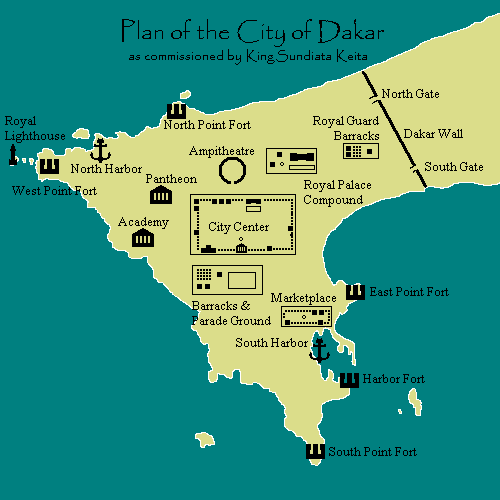

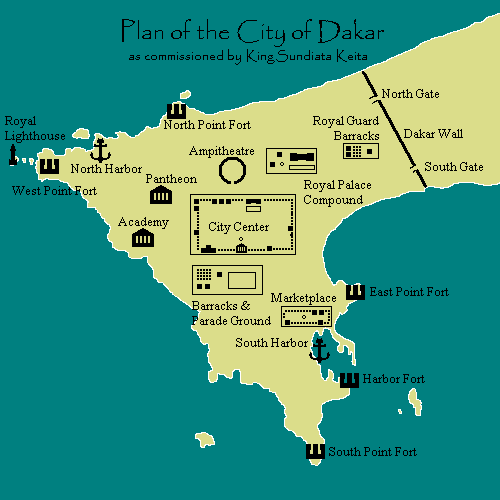

Sundiata Keita, wise in his old age, knew that the only way to fully assimilate the Senegal country would be to establish a great economic and cultural center within it. From this center of Malian power, the prosperity and culture of the kingdom would spread outward, fully integrating the western lands into Sundiata's great empire. Furthermore, this great city would strengthen the power and prestige of the Malian state as a whole, increasing her greatness on the world stage.

And so the King gathered in Timbuktu the finest architects, engineers, city planners, geographers, seafarers, merchants, and holy men in all the kingdom. Sundiata commissioned these men to locate a site for his new city, and to then create a design for that city. Once a satisfactory plan had been created and approved, they were to immediately begin construction.

The location chosen by the geographers and seafarers was one of the most strategically important sites in the entirety of Sundiata's kingdom. The plot of land which would become Dakar was geographically blessed in several ways: firsty, its location at the westernmost point in Africa made it ideal for maritime trade with the North; secondly, its location at the turning point of the African Hump gave it command of all maritime trade between the North and South; thirdly, its location at the mouth of the Senegal River provided it with access to the inland country; fourthly, its location on a peninsula made it easilly defensible against attack; and finally, it possessed not one but two excellent harbors. These attributes made the site the ideal location for a new city to anchor Malian power along the Senegal.

The architects, engineers, city planners, merchants, and priests collaborated to create a plan for the new city. The urban planners proposed that particular areas be zoned off for specific purposes; it was thus agreed that the heart of the city would be a planned city center, housing cultural institutions, temples, and commercial businesses. The merchants proposed that a single large marketplace be constructed to facilitate commerce in the city, and that it be located close to the main seaport. The King had ordered that the city be impregnable, and so the wise men worked closely with military commanders and engineers to plan out the city's defenses. A wall was to be built to defend the eastern side of Dakar from attacks from the mainland; fortifications were to be constructed at strategic points to defend against attacks from the sea. A large military compound was to be built, along with a smaller barracks for the Royal Guard, near the ground of a secondary royal residence.

The seafarers, realizing how important Dakar would be to sailing the western waters, proposed that a lighthouse be built on the westernmost point in the city, which would in turn be the westernmost point in mainland Africa. The engineers concurred, and designed a large and magnificent lighthouse which would stand on the western tip of Africa, guiding sailors into Dakar's North Harbor and around the Hump.

The High Priest himself contributed to the design of Dakar. Having been spoken to in a dream by one of the gods, he declared that if a temple dedicated to all the gods and spirits were built in Dakar, the young city would be blessed for all time. Thus, a large Pantheon was designed by a brilliant young provincial architect, and the greatest artists, artisans, and stoneworkers in the land were hired to work on the massive project.

As the Malian people put great emphasis on education, it was decided that a great Academy, rivaling the one in Timbuktu, should be built in Dakar; this institution would draw the brightest minds and greatest talents in the western country to Dakar, where they would collaborate to improve their own brilliance while also educating future generations of Malian scholars, politicians, philosophers, and commanders. The thoughts and discoveries eminating from this institution of learning would spread and enlighten the entire kingdom. Here, too, would be accumulated great works of literature and scholarship, to preserve the history, tradition, and learning of Mali.

The King believed that he should keep his people happy, and one means to this end was mass entertainment. He therefore commissioned in his new city a large Ampitheatre, where for a small admission the public could go to see a play, hear a concert, listen to the retelling of traditional stories, view a dance show, watch a sporting event, or take in a lecture by scholars from the Academy. In this way the massed would be entertained and enlightened.

These things, and many more, were compiled into a comprehensive plan, which was then proposed to Sundiata. The King was thrilled, finding the proposal to be everything he had hoped for. The city was ordered built immediately. Engineers, artisans, masons, woodworkers, and laborers were gathered to construct the new center of Malian power in the West; priests were brought in to maintain the temples, and scholars to form the Academy faculty. People were moved out of small villages in the Senegal country to populate the new metropolis.

This was to be the new city. This was Dakar.

Sundiata Keita, wise in his old age, knew that the only way to fully assimilate the Senegal country would be to establish a great economic and cultural center within it. From this center of Malian power, the prosperity and culture of the kingdom would spread outward, fully integrating the western lands into Sundiata's great empire. Furthermore, this great city would strengthen the power and prestige of the Malian state as a whole, increasing her greatness on the world stage.

And so the King gathered in Timbuktu the finest architects, engineers, city planners, geographers, seafarers, merchants, and holy men in all the kingdom. Sundiata commissioned these men to locate a site for his new city, and to then create a design for that city. Once a satisfactory plan had been created and approved, they were to immediately begin construction.

The location chosen by the geographers and seafarers was one of the most strategically important sites in the entirety of Sundiata's kingdom. The plot of land which would become Dakar was geographically blessed in several ways: firsty, its location at the westernmost point in Africa made it ideal for maritime trade with the North; secondly, its location at the turning point of the African Hump gave it command of all maritime trade between the North and South; thirdly, its location at the mouth of the Senegal River provided it with access to the inland country; fourthly, its location on a peninsula made it easilly defensible against attack; and finally, it possessed not one but two excellent harbors. These attributes made the site the ideal location for a new city to anchor Malian power along the Senegal.

The architects, engineers, city planners, merchants, and priests collaborated to create a plan for the new city. The urban planners proposed that particular areas be zoned off for specific purposes; it was thus agreed that the heart of the city would be a planned city center, housing cultural institutions, temples, and commercial businesses. The merchants proposed that a single large marketplace be constructed to facilitate commerce in the city, and that it be located close to the main seaport. The King had ordered that the city be impregnable, and so the wise men worked closely with military commanders and engineers to plan out the city's defenses. A wall was to be built to defend the eastern side of Dakar from attacks from the mainland; fortifications were to be constructed at strategic points to defend against attacks from the sea. A large military compound was to be built, along with a smaller barracks for the Royal Guard, near the ground of a secondary royal residence.

The seafarers, realizing how important Dakar would be to sailing the western waters, proposed that a lighthouse be built on the westernmost point in the city, which would in turn be the westernmost point in mainland Africa. The engineers concurred, and designed a large and magnificent lighthouse which would stand on the western tip of Africa, guiding sailors into Dakar's North Harbor and around the Hump.

The High Priest himself contributed to the design of Dakar. Having been spoken to in a dream by one of the gods, he declared that if a temple dedicated to all the gods and spirits were built in Dakar, the young city would be blessed for all time. Thus, a large Pantheon was designed by a brilliant young provincial architect, and the greatest artists, artisans, and stoneworkers in the land were hired to work on the massive project.

As the Malian people put great emphasis on education, it was decided that a great Academy, rivaling the one in Timbuktu, should be built in Dakar; this institution would draw the brightest minds and greatest talents in the western country to Dakar, where they would collaborate to improve their own brilliance while also educating future generations of Malian scholars, politicians, philosophers, and commanders. The thoughts and discoveries eminating from this institution of learning would spread and enlighten the entire kingdom. Here, too, would be accumulated great works of literature and scholarship, to preserve the history, tradition, and learning of Mali.

The King believed that he should keep his people happy, and one means to this end was mass entertainment. He therefore commissioned in his new city a large Ampitheatre, where for a small admission the public could go to see a play, hear a concert, listen to the retelling of traditional stories, view a dance show, watch a sporting event, or take in a lecture by scholars from the Academy. In this way the massed would be entertained and enlightened.

These things, and many more, were compiled into a comprehensive plan, which was then proposed to Sundiata. The King was thrilled, finding the proposal to be everything he had hoped for. The city was ordered built immediately. Engineers, artisans, masons, woodworkers, and laborers were gathered to construct the new center of Malian power in the West; priests were brought in to maintain the temples, and scholars to form the Academy faculty. People were moved out of small villages in the Senegal country to populate the new metropolis.

This was to be the new city. This was Dakar.

das

Regeneration In Process

Because some people *coughdascough* are being arrogant perks, and because theoretically das gave up the copyright to his idea when he shared it with me about two months before he put it into action, and because I'd like seeing stories which can have actual character development without immortal kings, I'm probably going to switch to an ITNES system soon enough. Say, in the next three turns.

What say ye, NESers?

*shrugs*

If you're talking about my suggestion that 100 years MIGHT possibly be enough for a little bit of marching and a marginally larger bit of genocide...

Um, anyhow, I like it the way it is, I would still like it if changed if you remain dedicated to it.

Grandmaster

Deity

Xen said:OOC: looks suspiciouslly like a certina city in eastern europe.....

OOC: The underlying terrain is in fact a map of modern Dakar that I pulled off Google and cleared of its details (place names, arondissement boundaries, etc); any similarity to Constantinople in terms of what is within the city is simply a coincidence owing to my intention to make Dakar as important and powerful a city as OTL Constantinople.

I don't understand....Xen said:well, you didnt say I couldnt bleed your eyeballs either, so uhhh, next time, uhhh, specify that i cant, in fact belled your eyeballs, or, if I can, to what extent they can be blead (blead to death, blead to half infaltion, and so on) specifics NK, I need specifics!

North King

blech

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2004

- Messages

- 18,165

Oh dear, not again...

I'm working on it, all right?

I'm working on it, all right?

Similar threads

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 311

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 163

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 293