You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Screenshots Thread

- Thread starter civverguy

- Start date

Ah, yes, thureophoroi/thorakitai are also in EB, but for me they're usually too expensive to serve as anything other than line infantry/skirmishers in the field armies. I keep a tight rein on my wallet in that game, especially in early game, due to the massive upkeep stuff.Theurophoroi (because they're good enough to serve as reliable infantry in addition to be fast enough to be skirmishers), but that's about it..

Can you say "Anarchronism?" I knew you could.

Cheezy the Wiz

Socialist In A Hurry

They cost a bit less than hoplites do in RTR, but more than most other skirmishers do (apart from Illyrian Mercenaries, which are badass omgwtf), so they make a good, flexible, and reliable Greek counterpart to Roman Auxilia. I'd describe them as "cost-effective."

Solid. You know what are one of the most cost-effective units in EB? The Greek sphendonetai, the slingers. The dudes in the development team, I guess, were struck by how many ancient armies included them, and sought to justify that. Sphendonetai can really whittle down enemy light infantry, with insane range. Nice and convenient, lets me keep my cavalry for destruction of the enemy horsemen and enveloping.They cost a bit less than hoplites do in RTR, but more than most other skirmishers do (apart from Illyrian Mercenaries, which are badass omgwtf), so they make a good, flexible, and reliable Greek counterpart to Roman Auxilia. I'd describe them as "cost-effective."

Patrick555

Chieftain

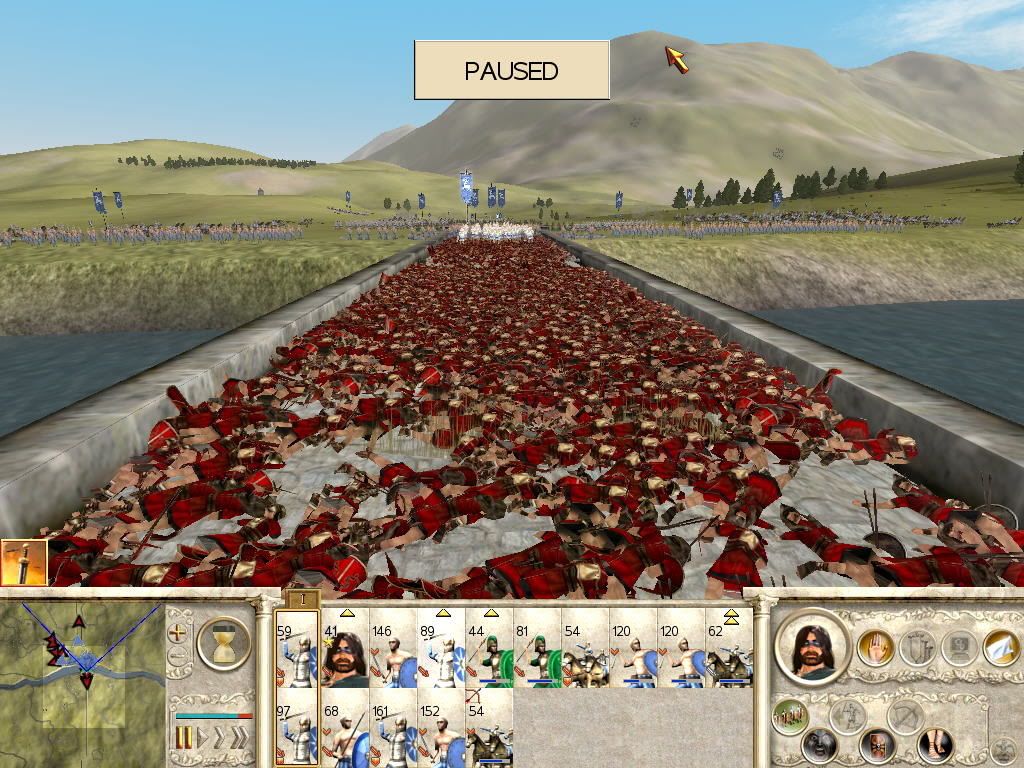

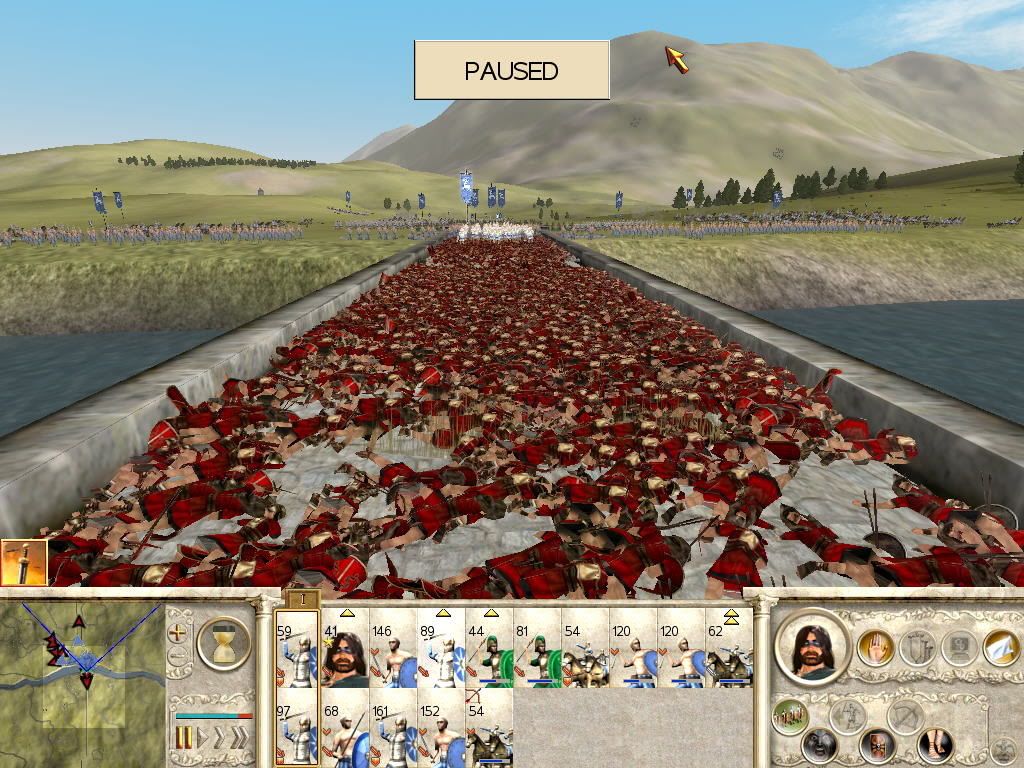

Well, To bring this topic come alive here is my clear victory of My seleucid adventure with Egyptians. Anyway I've been playing on hard difficult of battle but even though it's hard it wasn't for me as exhaustive as it would be on very hard difficut level.There's one shame that's not a heroic one.

Cheezy the Wiz

Socialist In A Hurry

My Russian empire, around 1300 AD.

Allied with Mongols and Byzantines (who by some strange happening are at war with one another, yet still allied to me ), at war with the English. Once that is concluded, I will either move against the Milanese, Sicilians, and Papacy, solidifying my southern front before I turn around and make my drive for Jerusalem. I figure by then the Byzantines will have been eliminated, which means a tough war against the Golden Horde. Fortunately I have omgwtf amounts of money to draw from, all the more when I conquer the areas previously discussed.

), at war with the English. Once that is concluded, I will either move against the Milanese, Sicilians, and Papacy, solidifying my southern front before I turn around and make my drive for Jerusalem. I figure by then the Byzantines will have been eliminated, which means a tough war against the Golden Horde. Fortunately I have omgwtf amounts of money to draw from, all the more when I conquer the areas previously discussed.

Allied with Mongols and Byzantines (who by some strange happening are at war with one another, yet still allied to me

), at war with the English. Once that is concluded, I will either move against the Milanese, Sicilians, and Papacy, solidifying my southern front before I turn around and make my drive for Jerusalem. I figure by then the Byzantines will have been eliminated, which means a tough war against the Golden Horde. Fortunately I have omgwtf amounts of money to draw from, all the more when I conquer the areas previously discussed.

), at war with the English. Once that is concluded, I will either move against the Milanese, Sicilians, and Papacy, solidifying my southern front before I turn around and make my drive for Jerusalem. I figure by then the Byzantines will have been eliminated, which means a tough war against the Golden Horde. Fortunately I have omgwtf amounts of money to draw from, all the more when I conquer the areas previously discussed.Cheezy the Wiz

Socialist In A Hurry

LightSpectra

me autem minui

The Revival of Rome, Pt. I.

I'm playing as the Eastern Roman Empire, and I'm stagnating quite a bit. I managed to use swift and unexpected attacks to blitz up to Budapest, but my war with Venice is slowly draining my efforts; in addition to this, the Holy Roman Empire is becoming increasingly concerned with my rapid expansions, so I expect a war with them sometime soon. With my resources and manpower being drained, I expect this to be the apex of the Greek Empire.

Then a Jihad is declared against Constantinople, and the Turks quickly amass their forces to, what I could assume, to crush my weak position in western Anatolia and then cross the Bosphorus and annihilate me. This looks grim.

However, they do something I didn't expect. I have control of the Crimea and so, my naval control over the Black Sea up until this point was uncontested. Instead of a land war with me, the Turks decide for a quick victory by building an armada, and then using troops trained in the Caucasus and eastern Anatolia to land just north of Constantinople and bypass my defenses. Leaving their forces without supplies in the middle of my territory means that they can't continue the pressure on me until I fail; if they didn't take the city now, the Jihad will fail.

While they could have economically drained me from the east and finished me off for good, their leap for a quick victory was a grave error. As their legion began its siege of Constantinople, one of my armies, lead by the Crown Prince, surrounded the Turkish crusaders. They weren't starving my capital to death in the middle of my own empire.

Realizing that they were trapped, they decided to go out for an all-out attack on the city. The Theodosian Walls proved to be impenetrable, and their attack force was easily crushed, while the escapees were butchered by the Prince's army.

Losing an entire legion without doing a bit of economic damage to me would lead to the downfall of the Turks. The Crown Prince plus another force departing from Antioch would lead a two-pronged attack against the Turkish nation and begin the revival of the Great Roman Empire.

I'm playing as the Eastern Roman Empire, and I'm stagnating quite a bit. I managed to use swift and unexpected attacks to blitz up to Budapest, but my war with Venice is slowly draining my efforts; in addition to this, the Holy Roman Empire is becoming increasingly concerned with my rapid expansions, so I expect a war with them sometime soon. With my resources and manpower being drained, I expect this to be the apex of the Greek Empire.

Then a Jihad is declared against Constantinople, and the Turks quickly amass their forces to, what I could assume, to crush my weak position in western Anatolia and then cross the Bosphorus and annihilate me. This looks grim.

However, they do something I didn't expect. I have control of the Crimea and so, my naval control over the Black Sea up until this point was uncontested. Instead of a land war with me, the Turks decide for a quick victory by building an armada, and then using troops trained in the Caucasus and eastern Anatolia to land just north of Constantinople and bypass my defenses. Leaving their forces without supplies in the middle of my territory means that they can't continue the pressure on me until I fail; if they didn't take the city now, the Jihad will fail.

While they could have economically drained me from the east and finished me off for good, their leap for a quick victory was a grave error. As their legion began its siege of Constantinople, one of my armies, lead by the Crown Prince, surrounded the Turkish crusaders. They weren't starving my capital to death in the middle of my own empire.

Realizing that they were trapped, they decided to go out for an all-out attack on the city. The Theodosian Walls proved to be impenetrable, and their attack force was easily crushed, while the escapees were butchered by the Prince's army.

Losing an entire legion without doing a bit of economic damage to me would lead to the downfall of the Turks. The Crown Prince plus another force departing from Antioch would lead a two-pronged attack against the Turkish nation and begin the revival of the Great Roman Empire.

The Famous History of the Life of Emperor Henry V

Following Heinrich IV's coronation by Pope Gregory VII in 1084, the Kaiser, while remaining in Italy to keep a tight grip on his territories in Romagna, dispatched several talented subordinates to the north to crush the many antikings and other rebellious vassals that had popped up during the investiture conflict earlier. Of these, the greatest were three men: Friedrich, herzog von Schwaben, who boldly seized Hamburg and Magdeburg from the Sachsen rebel Hermann von Salm; Heinrich's son, also named Heinrich, King of the Romans, who fought in Switzerland and Lothringen; and the warrior monk and former ministeriale Hermann von Salza, who reasserted imperial power in Böhmen and then cunningly captured Schlesien from a rebellious Piast duke. In the 1110s von Salza would go on to march on Stettin, home of the Wendish people, and drive them out, spearheading a great effort at conversion of the conquered populace that went surprisingly rapidly; German clergy were attracted from all over the Reich and by 1140 the Wends had been largely Christianized. German settlers soon began to arrive to populate the towns that were springing up there in Pommern, and a herzogtum was created out of the region.

Kaiser Heinrich himself had to deal with the vicissitudes of Italian politics. The distractions of the other great Italian states, however, allowed him to seize Tuscany, which had previously been semi-independent, in 1090, thus establishing a solid band of Imperial territory across north-central Italy. The direct Imperial-ruled areas thus became a counterpart to the four already-extant Italian states. In the north, the Serenissima of Venizia, which controlled colonies in Greek Crete and Rhodes, also ruled over Dalmatia and inland Illyria, including Croatia. To their west, the newly coalescent Lombard League, dominated by the Podestà of Milano and the Serenissima of Genova, began to claim alienated Imperial territory in Provence. To the south, the newly formed Sicilian duchy of Robert Guiscard and his Normans had a tight grip on Napoli. And finally, in the middle of it all, Pope Gregory, having fully reconciled himself to imperial power due to important concessions made by the Kaiser, ruled the Patrimony of St. Peter, in firm alliance - as equals, politically - with the Empire.

Heinrich sought to protect his western flanks and his Italian territories via two critical alliances, negotiated in the 1090s. In 1093 the French were convinced to allow a marriage alliance between the King of the Romans and the princess Gisele; Heinrich elected to overlook the French conquest of Imperial Burgund in order to make his long western border a quiet one. The following year an Imperial princess was married to Guiscard of Sicily's son Bohemund, with an attendant alliance there as well. Kaiser Heinrich was firmly convinced that any war in south Italy would be senseless without control of the Po River Valley. And finally, the Danish settlement in the north was recognized. Though Hamburg had returned to the Imperial fold along with Magdeburg, Holland's story was different: a Danish army had conquered it, and war nearly erupted between the Empire and the Danes over the issue. The Kaiser, however, elected not to pursue alienated Holland; Italy became the priority.

The Kaiser's machinations did not bear fruit, though, until after his death in 1123. His son, Heinrich V, was crowned Kaiser by Pope Eugenius III the next year, fresh from a victory outside Metz over some Lothringen rebels. Kaiser Heinrich V was childless - his French wife, unfortunately, was barren - but the position of King of the Romans was unexpectedly filled by his confederate, Hermann von Salza. Von Salza, following his Bohemian and Silesian victories, had been the man to help the new order of warrior monks, the Teutonic Knights, found their headquarters in Frankfurt am Main, bringing in a new source of powerful allied soldiers for the Reich. But this service and his successful eastern campaigns still, to many contemporaries, did not remotely qualify him to be the heir presumptive to the Imperial throne. Heinrich V's motives for choosing von Salza over his own cousin or over the herzog von Schwaben will forever remain mysterious. But for now, von Salza was reluctantly accepted in his new office. Many of his detractors doubtless recognized the age difference between him and his adoptive 'father' and believed he would never come to the throne anyway.

Heinrich V had to deal with a series of crises in southern France and northern Italy immediately upon his accession. The Lombard League, searching for a good route for expansion, settled its eye on the Imperial ally, the Kingdom of France. The French royal armies were largely occupied in the north, pacifying the Duchy of Brittany and reasserting royal control over Flanders, and thus the only forces in the way of the Milanese armies were feudal retainers, hardly a match for the crack urban militiamen of Milan. Genoese fleets swept the Mediterranean of the weak French fleet and initiated a grand blockade of Languedoc and Provence in 1126; at the same time, a grand offensive began on land, across the Alps. Responding to this offensive forced the French to abandon their Breton and Flemish campaigns. The King was also unable to prevent the alienation of the Duchy of Aquitaine to the Castilian crown, by way of a fortuitous marriage.

Here would seem a perfect opportunity for the Empire to intervene to save its ally and crush the League, fulfilling two major foreign policy objectives at once. But the Kaiser's attention was turned elsewhere, repeatedly. While he gathered his army in Switzerland to debouch south into Italy, a rebellion popped up in Sachsen, combined with threatening Danish movements with large armies near the frontier, even crossing it a few times. Since the Danish king Erik reunited Scandinavia in 1129, Danish troops had been appearing along the frontier with frightening regularity, and it appeared that Erik harbored expansionist designs on north Germany to link his duchy in Holland to the rest of his royal holdings. Imperial attention was diverted; the Danish war scare turned out to be just that, but the rebels took several years to bring to heel fully. A Hungarian border war erupted near almost-undefended Wien in 1037, again occupying Imperial attention. Budapest fell in 1041, but the Kaiser willingly yielded it in exchange for peace. (Hungary and the Byzantine Empire were at the time fighting a war in the northern Balkans; the Kaiser's peace settlement with the Magyars returned Budapest but only in exchange for Sofia, which was then rewarded to the Byzantines along with an alliance, sealed by the marriage of an Imperial princess to the crown prince Ioannis.)

So it was not until 1150 that the Kaiser could turn his attention southwards again, and by then the situation had gotten infinitely worse. The Milanese had defeated the French royal army that had been dispatched against them; the Podestà, Gerardo, had crushed the French crown prince in 1145 at a titanic battle, fought at Mâcon south of Dijon. The following year the Milanese used their leverage with Pope Innocent II to have the French king excommunicated; in 1148 they convinced the same Pope to call for all Christian princes to send soldiers to fight the French king, with the goal of capturing Toulouse in Languedoc.

This "Crusade", as some called it, was mostly a dead letter. Not a single Christian king permitted his nobility to join; no other Christian states entered war with the Kingdom of France. Most recognized the whole thing as a political ploy by the Lombard League and refused to have any part of it. But in several countries, especially England and Poland, the nobility was champing at the bit for some action, and for awhile it seemed as though war would break out after all; it was in this climate that Heinrich V finally collected his army north of the Alps and sent emissaries to the Podestà and the Genoese assembly to reaffirm their loyalty to their nominal sovereign, the Kaiser, by halting their invasion of France. The entreaty was summarily refused; the Kaiser then led his host south in May of 1050.

He was aided by the lack of any major Lombard League armies in Italy. The main force was at that time protecting newly-conquered Dijon from a French counterattack, under the Doge of Genova; the Podestà was administering conquered Nice and Marseilles. Lombardy itself was woefully underdefended, and Heinrich captured Milano itself with ease in 1051 after a brief siege and assault. But by then forces were marshaling against him. A fresh Sachsen rebellion diverted Hermann von Salza and his reinforcements, leaving only the Kaiser's personal army in Italy to defend against the Milanese that were hastily marching back over the Alps. Heinrich departed Milano to prevent from being trapped in the city, and moved south to Alessandria in the spring of 1051; the Doge followed him, and finally in the winter of 1051-2 the two armies clashed at Piacenza. The German infantry held up admirably against the Milanese urban spearmen, despite being outnumbered; German levy archers hit back blow for blow against the Genoese pavise crossbowmen. But the German cavalry delivered the coup de grâce, spearheaded by the Kaiser and by knights of the Teutonic Order; confronted by the irresistible Imperial horse charge, the Lombard army gave way, and Heinrich had his first victory. He proceeded south, across the Ligurian mountains, and in 1154 besieged Genova itself.

This of course brought another army down on his head, commanded by the Podestà himself, one Guglielmo. At Voltri on the Ligurian coast, Heinrich fought the Lombard League's second major army, once again outnumbered due to a sizable contingent of reinforcements from within Genova that sallied to fight the Imperial force. With a Lombard army that had nearly twice his own depleted numbers, the Kaiser ably operated on tactical interior lines; the Milanese infantry was driven back in front, and then while the crack German cavalry pursued them the German infantry turned round to face the Genoese urban levies in a long, sanguinary contest that only ended when the German cavalry returned to crush the Italian troops. Genova lay open to the Imperial army, which revenged its tribulations over the last few months by sacking the city.

In the later part of the 1150s, the war died down a bit; what Lombard League-allied forces remained guarded the Alpine passes well, and were aided by partisan outbreaks in Lombardy and Liguria. Heinrich also wished to install friendly stable governments in his new Italian territories, a delicate mixture of carrot and stick; eventually, the Serenissima in Genova was abolished and an imperial Grafschaft established in its place; Milano itself was turned into a free city, while much of the remainder of Lombardy became imperial lands. The French, for their part, used this time space to recapture Dijon, and successfully conclude their Breton war. The tide had clearly turned after the Battle of Voltri. In 1164 Kaiser Heinrich moved with his grizzled veterans through the cleared passes in the Maritime Alps and besieged the final Lombard League holdouts in Marseilles, led by a Milanese nobleman refugee, Giordano Attendolo, and garrisoned by a small force of sailors and urban militia armed in the Italian style. The following year the Imperial army was able to assault the walls of the final Lombard stronghold; a coordinated push through the streets from several directions was conducted by the infantry, but at the town center Attendolo held out with two hundred retainers and militia. German sergeant spearmen moved in and engaged the diehards, while the Kaiser himself led a force of retainers and Teutonic Knights along a side alleyway for a charge into Attendolo's troops' unprotected rear. The Kaiser began the charge, and four hundred horsemen hurtled down the road towards the melee in the town square...but a few of Attendolo's men saw them coming, fifty urban spearmen turned around, and the charge was partially broken before it swept all before it.

There were only thirteen casualties of the storming of Marseilles, but the one that mattered most was the Kaiser, dead at 39, impaled by a spear during that final climactic charge. His second-in-command at Marseilles, Hermann Balk, quickly took charge and limited looting in the city, and had the unenviable task of explaining to the assembled Reichstag a few weeks later that the young dynamo Kaiser had died at the moment of his final victory. And the King of the Romans, Hermann von Salza, aged 52, the low-born ministeriale that had, in a span of a few decades, ascended to the heights of power, traveled to Rome to have the diadem placed on his head by Pope Clement IV.

Europe in 1165 at the ascension of Hermann I, Römisch-deutscher Kaiser

---

Weird dates and ages explained away by the broken M2TW age system, which doesn't match up with the year at all.

Difficulty is H/H.

I'm pretty angry about that death, which happened an hour ago. He had friggin' 9 command stars and was almost full up on Chivalry, Authority, and Piety too. One of the best generals I've had, and he got promoted pretty unusually fast. So the weird M2TW heir system picks Hermann von Salza (a general I got by adoption in the early stages of the campaign, to much hilarity - he was, in OTL, the greatest of the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order, and his victories strangely coincided with the foundation of the Order in Frankfurt in-game) who in OTL was definitely not imperial stock by any stretch (and about a hundred years later to boot) as the heir to succeed Heinrich V. I'll probably bring in another update, this was a lot more fun to write up than I originally planned.

Sick of meddling in Byzantine wars to help them. They've been consistently losing to Hungarian armies in Bulgaria after losing it again a few years ago, and they also brilliantly decided to attack the Turks while they a) were already fighting a war in the west and b) still hadn't captured Smyrna for chrissakes. And then they sent most of the good part of their army north to capture Kiev and the Kalmuk steppe. I don't get the AI at all.

Sicily has been doing fantastically since we allied. They've been rolling over rebel settlements and just DoWed the Moors with two fullstacks marching through their North African domains. I expect great things from them. Should be a fun challenge in a hundred years or so.

Danish armies keep wandering around Hamburg in distressingly large numbers. I have a damn big army, but most of it is immobile and watching the AI in my north and east for any signs of trouble. Not enough to go on an offensive yet, but that'll change now that my south is clear. I'm still pretty sore about them stealing Antwerp from under my nose, too - they beat my besiegers to the punch by a single turn.

What annoys me is that the only Crusade so far was that lame one against French Toulouse. Nobody friggin joined, not even the Milanese, and the whole thing petered out pretty quickly, and used up a crusade slot that oughta have gone into Spain or the Levant. Now we have to wait until crusading armies are possible again. Stupid.

Oh, and Scotland never captured Inverness, but they just got Ireland, and are now at war with the English. I wonder how long it'll take the English to steamroll them. Do the Scots get the Wallace event even if they don't control Inverness?

If you read all this, you have my personal thanks.

Following Heinrich IV's coronation by Pope Gregory VII in 1084, the Kaiser, while remaining in Italy to keep a tight grip on his territories in Romagna, dispatched several talented subordinates to the north to crush the many antikings and other rebellious vassals that had popped up during the investiture conflict earlier. Of these, the greatest were three men: Friedrich, herzog von Schwaben, who boldly seized Hamburg and Magdeburg from the Sachsen rebel Hermann von Salm; Heinrich's son, also named Heinrich, King of the Romans, who fought in Switzerland and Lothringen; and the warrior monk and former ministeriale Hermann von Salza, who reasserted imperial power in Böhmen and then cunningly captured Schlesien from a rebellious Piast duke. In the 1110s von Salza would go on to march on Stettin, home of the Wendish people, and drive them out, spearheading a great effort at conversion of the conquered populace that went surprisingly rapidly; German clergy were attracted from all over the Reich and by 1140 the Wends had been largely Christianized. German settlers soon began to arrive to populate the towns that were springing up there in Pommern, and a herzogtum was created out of the region.

Kaiser Heinrich himself had to deal with the vicissitudes of Italian politics. The distractions of the other great Italian states, however, allowed him to seize Tuscany, which had previously been semi-independent, in 1090, thus establishing a solid band of Imperial territory across north-central Italy. The direct Imperial-ruled areas thus became a counterpart to the four already-extant Italian states. In the north, the Serenissima of Venizia, which controlled colonies in Greek Crete and Rhodes, also ruled over Dalmatia and inland Illyria, including Croatia. To their west, the newly coalescent Lombard League, dominated by the Podestà of Milano and the Serenissima of Genova, began to claim alienated Imperial territory in Provence. To the south, the newly formed Sicilian duchy of Robert Guiscard and his Normans had a tight grip on Napoli. And finally, in the middle of it all, Pope Gregory, having fully reconciled himself to imperial power due to important concessions made by the Kaiser, ruled the Patrimony of St. Peter, in firm alliance - as equals, politically - with the Empire.

Heinrich sought to protect his western flanks and his Italian territories via two critical alliances, negotiated in the 1090s. In 1093 the French were convinced to allow a marriage alliance between the King of the Romans and the princess Gisele; Heinrich elected to overlook the French conquest of Imperial Burgund in order to make his long western border a quiet one. The following year an Imperial princess was married to Guiscard of Sicily's son Bohemund, with an attendant alliance there as well. Kaiser Heinrich was firmly convinced that any war in south Italy would be senseless without control of the Po River Valley. And finally, the Danish settlement in the north was recognized. Though Hamburg had returned to the Imperial fold along with Magdeburg, Holland's story was different: a Danish army had conquered it, and war nearly erupted between the Empire and the Danes over the issue. The Kaiser, however, elected not to pursue alienated Holland; Italy became the priority.

The Kaiser's machinations did not bear fruit, though, until after his death in 1123. His son, Heinrich V, was crowned Kaiser by Pope Eugenius III the next year, fresh from a victory outside Metz over some Lothringen rebels. Kaiser Heinrich V was childless - his French wife, unfortunately, was barren - but the position of King of the Romans was unexpectedly filled by his confederate, Hermann von Salza. Von Salza, following his Bohemian and Silesian victories, had been the man to help the new order of warrior monks, the Teutonic Knights, found their headquarters in Frankfurt am Main, bringing in a new source of powerful allied soldiers for the Reich. But this service and his successful eastern campaigns still, to many contemporaries, did not remotely qualify him to be the heir presumptive to the Imperial throne. Heinrich V's motives for choosing von Salza over his own cousin or over the herzog von Schwaben will forever remain mysterious. But for now, von Salza was reluctantly accepted in his new office. Many of his detractors doubtless recognized the age difference between him and his adoptive 'father' and believed he would never come to the throne anyway.

Heinrich V had to deal with a series of crises in southern France and northern Italy immediately upon his accession. The Lombard League, searching for a good route for expansion, settled its eye on the Imperial ally, the Kingdom of France. The French royal armies were largely occupied in the north, pacifying the Duchy of Brittany and reasserting royal control over Flanders, and thus the only forces in the way of the Milanese armies were feudal retainers, hardly a match for the crack urban militiamen of Milan. Genoese fleets swept the Mediterranean of the weak French fleet and initiated a grand blockade of Languedoc and Provence in 1126; at the same time, a grand offensive began on land, across the Alps. Responding to this offensive forced the French to abandon their Breton and Flemish campaigns. The King was also unable to prevent the alienation of the Duchy of Aquitaine to the Castilian crown, by way of a fortuitous marriage.

Here would seem a perfect opportunity for the Empire to intervene to save its ally and crush the League, fulfilling two major foreign policy objectives at once. But the Kaiser's attention was turned elsewhere, repeatedly. While he gathered his army in Switzerland to debouch south into Italy, a rebellion popped up in Sachsen, combined with threatening Danish movements with large armies near the frontier, even crossing it a few times. Since the Danish king Erik reunited Scandinavia in 1129, Danish troops had been appearing along the frontier with frightening regularity, and it appeared that Erik harbored expansionist designs on north Germany to link his duchy in Holland to the rest of his royal holdings. Imperial attention was diverted; the Danish war scare turned out to be just that, but the rebels took several years to bring to heel fully. A Hungarian border war erupted near almost-undefended Wien in 1037, again occupying Imperial attention. Budapest fell in 1041, but the Kaiser willingly yielded it in exchange for peace. (Hungary and the Byzantine Empire were at the time fighting a war in the northern Balkans; the Kaiser's peace settlement with the Magyars returned Budapest but only in exchange for Sofia, which was then rewarded to the Byzantines along with an alliance, sealed by the marriage of an Imperial princess to the crown prince Ioannis.)

So it was not until 1150 that the Kaiser could turn his attention southwards again, and by then the situation had gotten infinitely worse. The Milanese had defeated the French royal army that had been dispatched against them; the Podestà, Gerardo, had crushed the French crown prince in 1145 at a titanic battle, fought at Mâcon south of Dijon. The following year the Milanese used their leverage with Pope Innocent II to have the French king excommunicated; in 1148 they convinced the same Pope to call for all Christian princes to send soldiers to fight the French king, with the goal of capturing Toulouse in Languedoc.

This "Crusade", as some called it, was mostly a dead letter. Not a single Christian king permitted his nobility to join; no other Christian states entered war with the Kingdom of France. Most recognized the whole thing as a political ploy by the Lombard League and refused to have any part of it. But in several countries, especially England and Poland, the nobility was champing at the bit for some action, and for awhile it seemed as though war would break out after all; it was in this climate that Heinrich V finally collected his army north of the Alps and sent emissaries to the Podestà and the Genoese assembly to reaffirm their loyalty to their nominal sovereign, the Kaiser, by halting their invasion of France. The entreaty was summarily refused; the Kaiser then led his host south in May of 1050.

He was aided by the lack of any major Lombard League armies in Italy. The main force was at that time protecting newly-conquered Dijon from a French counterattack, under the Doge of Genova; the Podestà was administering conquered Nice and Marseilles. Lombardy itself was woefully underdefended, and Heinrich captured Milano itself with ease in 1051 after a brief siege and assault. But by then forces were marshaling against him. A fresh Sachsen rebellion diverted Hermann von Salza and his reinforcements, leaving only the Kaiser's personal army in Italy to defend against the Milanese that were hastily marching back over the Alps. Heinrich departed Milano to prevent from being trapped in the city, and moved south to Alessandria in the spring of 1051; the Doge followed him, and finally in the winter of 1051-2 the two armies clashed at Piacenza. The German infantry held up admirably against the Milanese urban spearmen, despite being outnumbered; German levy archers hit back blow for blow against the Genoese pavise crossbowmen. But the German cavalry delivered the coup de grâce, spearheaded by the Kaiser and by knights of the Teutonic Order; confronted by the irresistible Imperial horse charge, the Lombard army gave way, and Heinrich had his first victory. He proceeded south, across the Ligurian mountains, and in 1154 besieged Genova itself.

This of course brought another army down on his head, commanded by the Podestà himself, one Guglielmo. At Voltri on the Ligurian coast, Heinrich fought the Lombard League's second major army, once again outnumbered due to a sizable contingent of reinforcements from within Genova that sallied to fight the Imperial force. With a Lombard army that had nearly twice his own depleted numbers, the Kaiser ably operated on tactical interior lines; the Milanese infantry was driven back in front, and then while the crack German cavalry pursued them the German infantry turned round to face the Genoese urban levies in a long, sanguinary contest that only ended when the German cavalry returned to crush the Italian troops. Genova lay open to the Imperial army, which revenged its tribulations over the last few months by sacking the city.

In the later part of the 1150s, the war died down a bit; what Lombard League-allied forces remained guarded the Alpine passes well, and were aided by partisan outbreaks in Lombardy and Liguria. Heinrich also wished to install friendly stable governments in his new Italian territories, a delicate mixture of carrot and stick; eventually, the Serenissima in Genova was abolished and an imperial Grafschaft established in its place; Milano itself was turned into a free city, while much of the remainder of Lombardy became imperial lands. The French, for their part, used this time space to recapture Dijon, and successfully conclude their Breton war. The tide had clearly turned after the Battle of Voltri. In 1164 Kaiser Heinrich moved with his grizzled veterans through the cleared passes in the Maritime Alps and besieged the final Lombard League holdouts in Marseilles, led by a Milanese nobleman refugee, Giordano Attendolo, and garrisoned by a small force of sailors and urban militia armed in the Italian style. The following year the Imperial army was able to assault the walls of the final Lombard stronghold; a coordinated push through the streets from several directions was conducted by the infantry, but at the town center Attendolo held out with two hundred retainers and militia. German sergeant spearmen moved in and engaged the diehards, while the Kaiser himself led a force of retainers and Teutonic Knights along a side alleyway for a charge into Attendolo's troops' unprotected rear. The Kaiser began the charge, and four hundred horsemen hurtled down the road towards the melee in the town square...but a few of Attendolo's men saw them coming, fifty urban spearmen turned around, and the charge was partially broken before it swept all before it.

There were only thirteen casualties of the storming of Marseilles, but the one that mattered most was the Kaiser, dead at 39, impaled by a spear during that final climactic charge. His second-in-command at Marseilles, Hermann Balk, quickly took charge and limited looting in the city, and had the unenviable task of explaining to the assembled Reichstag a few weeks later that the young dynamo Kaiser had died at the moment of his final victory. And the King of the Romans, Hermann von Salza, aged 52, the low-born ministeriale that had, in a span of a few decades, ascended to the heights of power, traveled to Rome to have the diadem placed on his head by Pope Clement IV.

Europe in 1165 at the ascension of Hermann I, Römisch-deutscher Kaiser

---

Weird dates and ages explained away by the broken M2TW age system, which doesn't match up with the year at all.

Difficulty is H/H.

I'm pretty angry about that death, which happened an hour ago. He had friggin' 9 command stars and was almost full up on Chivalry, Authority, and Piety too. One of the best generals I've had, and he got promoted pretty unusually fast. So the weird M2TW heir system picks Hermann von Salza (a general I got by adoption in the early stages of the campaign, to much hilarity - he was, in OTL, the greatest of the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order, and his victories strangely coincided with the foundation of the Order in Frankfurt in-game) who in OTL was definitely not imperial stock by any stretch (and about a hundred years later to boot) as the heir to succeed Heinrich V. I'll probably bring in another update, this was a lot more fun to write up than I originally planned.

Sick of meddling in Byzantine wars to help them. They've been consistently losing to Hungarian armies in Bulgaria after losing it again a few years ago, and they also brilliantly decided to attack the Turks while they a) were already fighting a war in the west and b) still hadn't captured Smyrna for chrissakes. And then they sent most of the good part of their army north to capture Kiev and the Kalmuk steppe. I don't get the AI at all.

Sicily has been doing fantastically since we allied. They've been rolling over rebel settlements and just DoWed the Moors with two fullstacks marching through their North African domains. I expect great things from them. Should be a fun challenge in a hundred years or so.

Danish armies keep wandering around Hamburg in distressingly large numbers. I have a damn big army, but most of it is immobile and watching the AI in my north and east for any signs of trouble. Not enough to go on an offensive yet, but that'll change now that my south is clear. I'm still pretty sore about them stealing Antwerp from under my nose, too - they beat my besiegers to the punch by a single turn.

What annoys me is that the only Crusade so far was that lame one against French Toulouse. Nobody friggin joined, not even the Milanese, and the whole thing petered out pretty quickly, and used up a crusade slot that oughta have gone into Spain or the Levant. Now we have to wait until crusading armies are possible again. Stupid.

Oh, and Scotland never captured Inverness, but they just got Ireland, and are now at war with the English. I wonder how long it'll take the English to steamroll them. Do the Scots get the Wallace event even if they don't control Inverness?

If you read all this, you have my personal thanks.

Krusader1985

Chieftain

What happens when you make the Berbers playable?

Well, let's see...

All the flags are cluster ed! + They worship Baal, although the cities can only build Christian buildings...

ed! + They worship Baal, although the cities can only build Christian buildings...

The Berber flag is a skeletal hand on a black background, and the rebel flag is now a gray/black CAMEL on the standard rebel-gray background.

Also, the swords of my armies are all jet-black...

Now before you go tell me I ruined my BI forever, I played as the Celts later and ALL WAS NORMAL.

Here's another one fresh from today:

The Eastern Empire found three mountain men regiments all of the sudden, and was forced to fight them with what troops it had available.

My archers stood on the hill and rained down death, while my general lured them up next to the archers so they could get good volleys in. Then when the mountain men turned tail from the archers, my cavalry rode them down and routed them, one by one.

Well, let's see...

All the flags are cluster

ed! + They worship Baal, although the cities can only build Christian buildings...

ed! + They worship Baal, although the cities can only build Christian buildings...

The Berber flag is a skeletal hand on a black background, and the rebel flag is now a gray/black CAMEL on the standard rebel-gray background.

Also, the swords of my armies are all jet-black...

Now before you go tell me I ruined my BI forever, I played as the Celts later and ALL WAS NORMAL.

Here's another one fresh from today:

The Eastern Empire found three mountain men regiments all of the sudden, and was forced to fight them with what troops it had available.

My archers stood on the hill and rained down death, while my general lured them up next to the archers so they could get good volleys in. Then when the mountain men turned tail from the archers, my cavalry rode them down and routed them, one by one.

Two screenshots from Fourth Age Total War, just messing around in custom battle...

it has a very very high mountain in one custom battle map

I had a video on the same map where my dwarven archers that you see here engaged them from half the minimap away... the arrows reached the enemy column falling straight down... and killed perhaps 200 people in 100 yards. Units can't move very fast up that mountain. Next they came in range of my ballistas and the ammunition & the slope of the mountain sent them flying for perhaps 500 feet. I am a good distance measurer as well...

LightSpectra

me autem minui

The E:TW AI is much improved, but there are still some quirks. For example, I essentially re-produced the Franco-Prussian War here, only with far more severity: France has been reduced to Paris, which is in gross bankruptcy and has nothing to defend itself. I have troops burning all of their factories and ports and besieged their capital.

They're currently losing 10% of their GDP every year. France, when I was offering to settle for peace, has less wealth than the single region of Bavaria in the German empire.

For peace, I offered to give them 3,000 ducats and a temporary trade agreement in exchange for one of their colonies in South America. Seems fair enough, right? I quickly end their bankruptcy, severe depression and military occupation in exchange for a single slice of their empire. Well, they refuse; in fact, the only terms they'll settle for peace on is if I unload my entire treasury (roughly 7,000 ducats) and give them Alsace-Lorraine and the Rhineland. That doesn't even make sense; I'm close to simply annexing France altogether and they're demanding more territory than they had when the war began?

The one possibility I could think of is that they had a full stack coming from North America that they were going to use to defeat my armies. (Which is still illogical, since I could've destroyed their faction forever whenever I chose.) Well, I waited until Paris starved to death, and that didn't happen; and they were still arguing for hilarious peace terms. I finally rolled my eyes and just eliminated France.

Spoiler :

They're currently losing 10% of their GDP every year. France, when I was offering to settle for peace, has less wealth than the single region of Bavaria in the German empire.

For peace, I offered to give them 3,000 ducats and a temporary trade agreement in exchange for one of their colonies in South America. Seems fair enough, right? I quickly end their bankruptcy, severe depression and military occupation in exchange for a single slice of their empire. Well, they refuse; in fact, the only terms they'll settle for peace on is if I unload my entire treasury (roughly 7,000 ducats) and give them Alsace-Lorraine and the Rhineland. That doesn't even make sense; I'm close to simply annexing France altogether and they're demanding more territory than they had when the war began?

The one possibility I could think of is that they had a full stack coming from North America that they were going to use to defeat my armies. (Which is still illogical, since I could've destroyed their faction forever whenever I chose.) Well, I waited until Paris starved to death, and that didn't happen; and they were still arguing for hilarious peace terms. I finally rolled my eyes and just eliminated France.

Maniacal

the green Napoleon

it seems to me they used the exact same AI scripts from every previous game, and only tweaked them to work with new changes in Empire. Although it isn't quite as bad as it used to be.

LightSpectra

me autem minui

Spoiler :

I had to auto-resolve this battle, because my computer couldn't take 12,000 soldiers on the battlefield.

Maniacal

the green Napoleon

I think the game won't deploy all of them on the field anyways.

Daftpanzer

canonically ambiguous

Some pics from my first and so far only campaign of MTW2 that I played until victory. Minor victory that is. I'm not sure I've ever conquered the whole map even in MTW1. Venice single-handedly defeats the mongol invasion and owns you all.

Conquering stuff.

And more stuff.

The horrors of war.

Meanwhile, in an alternate universe, the Britons conquer all of italy.

Now I'm trying to get back into RTW. I have the BI expansion, but my internet conncetion doesn't quite stretch to downloading multi-gigabyte mods yet. Really, I am still a sprite aficionado at heart, but I suffer the battle-map mouse selection problem with the later GeForce cards and so I sadly cannot play Shogun or MTW1 on this comp.

Spoiler :

Conquering stuff.

Spoiler :

And more stuff.

Spoiler :

The horrors of war.

Spoiler :

Meanwhile, in an alternate universe, the Britons conquer all of italy.

Spoiler :

Now I'm trying to get back into RTW. I have the BI expansion, but my internet conncetion doesn't quite stretch to downloading multi-gigabyte mods yet. Really, I am still a sprite aficionado at heart, but I suffer the battle-map mouse selection problem with the later GeForce cards and so I sadly cannot play Shogun or MTW1 on this comp.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 54

- Views

- 1K