the following passages were perhaps my favorite of the entire essay. as many of my CFC friends know, i love military history and this is no expection. i was able to uncover some fabulous records and plenty of first-hand accounts of the pacification process in the P.I. also, i was able to C&P this passage with the footnotes! i was quite happy to find this out!

The roles of the American military in the Philippine Islands went beyond simply rooting out the insurgents. This dual-task of pacification and civil reconstruction will be shown to have a tremendous impact on the outcome of the war. However, it is important to note that these tasks varied greatly from one region of the Philippines to the next. In some areas, the resistance raged on for years while in others, it was disorganized and meager. For that reason, the variety of circumstances that the Americans encountered deserves mentioning. This chapter is not intended, however, to be a standard chronicle of military operations. Instead, the aim is to uncover the particular successes and failures that the U.S. military achieved while pacifying the Philippines. This examination begins with what is now known as the Second Battle of Manila. The goal is to uncover exactly what measures that were taken to secure the city and its surrounding barrios. The second example is the pacification efforts in the Visayan Islands. It will be shown how the American actions here had both positive and negative effects on the pacification efforts. The island of Negros is the next topic. Negros was considered to be the model for American pacification in the Philippines and as a result, it is extremely important that it be reviewed. Following this is an examination of the American efforts to pacify on the island of Samar. The goal of this section is to uncover and debunk the myths that are inevitably attached to it. The final and most interesting portion of this chapter is an analysis of the memoirs of James Parker, a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Cavalry. He was responsible for occupying two different regions of Luzon and it will be shown how his efforts there form a good part of the story in the Philippines that is not very well known.

The roles of the American military in the Philippine Islands went beyond simply rooting out the insurgents. This dual-task of pacification and civil reconstruction will be shown to have a tremendous impact on the outcome of the war. However, it is important to note that these tasks varied greatly from one region of the Philippines to the next. In some areas, the resistance raged on for years while in others, it was disorganized and meager. For that reason, the variety of circumstances that the Americans encountered deserves mentioning. This chapter is not intended, however, to be a standard chronicle of military operations. Instead, the aim is to uncover the particular successes and failures that the U.S. military achieved while pacifying the Philippines. This examination begins with what is now known as the Second Battle of Manila. The goal is to uncover exactly what measures that were taken to secure the city and its surrounding barrios. The second example is the pacification efforts in the Visayan Islands. It will be shown how the American actions here had both positive and negative effects on the pacification efforts. The island of Negros is the next topic. Negros was considered to be the model for American pacification in the Philippines and as a result, it is extremely important that it be reviewed. Following this is an examination of the American efforts to pacify on the island of Samar. The goal of this section is to uncover and debunk the myths that are inevitably attached to it. The final and most interesting portion of this chapter is an analysis of the memoirs of James Parker, a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Cavalry. He was responsible for occupying two different regions of Luzon and it will be shown how his efforts there form a good part of the story in the Philippines that is not very well known.

US troops on the outskirts of Manila, 1899

A half a year worth of waiting and negotiating erupted into full-scale war on February 4, 1899. Filipino accounts of the incident vary from that of the American accounts. Linn noted that the fogginess of these initial events in the San Juan del Monte section of Manila are matters of strong dispute among Filipino and American historians alike.[1] However, it is clear that the encounter occurred at night, several months after Aguinaldos Army of Liberation began digging trenches, artillery emplacements and an impressive array of earthworks on Manilas perimeter. The U.S. Army estimated that between fifteen and forty thousand insurgent troops formed a loose ring around the city at the time hostilities commenced. The American boots on the ground in the Philippines at this time was about 800 officers and a little more than twenty thousand troops. Seventy-seven of the officers and another 2338 troops were either in the southern theater of Cavite or aboard the transports off the coast of Iloilo City. An estimated eight-thousand troops were in Manila and another eleven thousand were in a sixteen mile-wide, home plate-shaped defensive line extending from Manila to the west and extending eastwards. Two brigades were garrisoned at the western banks of the Pasig River: McArthurs 2nd Division and Brig. Gen. Harrison G. Otiss (no relation) 1st Brigade. Brig. Gen. Irwin Hales 2nd Brigade extended the American lines further eastward in order to link up with Otiss lines. The 1st South Dakota were dug in around San Mateo near the Pasig River, the 1st Colorado at Samplac on the southern side of the Pasig, and at the point, the 1st Nebraska in Santa Mesa. The remaining American lines were made up Maj. Andersons 1st Division and Brig. Gen. Charles Kings 1st Brigade near Blockhouse 12. Brig. Gen. Samuel Overshines 2nd Brigade rounded at the southern flank as they stretched from Kings lines at Blockhouse 12 to Manila Bay. These troops that formed the American lines around Manila were referred to as the 8th Corps. These somewhat over-stretched American lines stood a good chance of being either overran or surrounded.[2]

For our European and Asian friends who may not know what a 'home plate shaped' design is. it is a reference to the game of baseball.

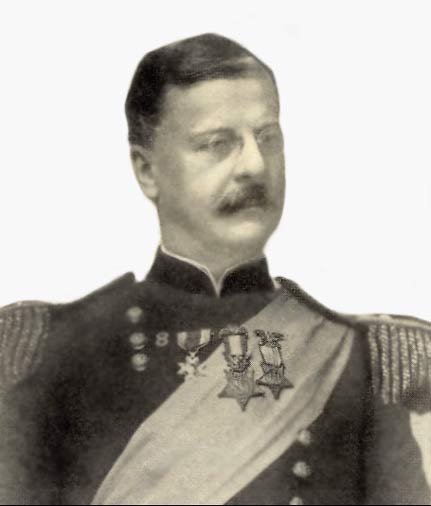

Arthur MacArthur

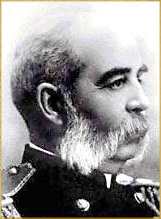

Brig. Gen Harrison G. Otis

As soon as the hostilities erupted on the evening of February 4, Gen. Robert P. Hughes ordered three regiments of the citys Provost Guard onto the streets of Manila to quell the disturbances as they began sealing off thoroughfares, dispersing large gatherings, and keeping a close watch on the suspected neighborhoods.[3] The Guards arrested dozens, perhaps hundreds of suspects and fended off a possible disaster for the 8th Corps.[4] However, the street battles continued in other sections of the city. Lt. Col. Victor Duboce and four companies of the 1st California of Kings Brigade were taking heavy sniper fire from the buildings in the Manila suburb of Paco. A house-to-house fight ensued and King ordered all buildings suspected of housing or providing cover for the snipers to be torched. The troops complied and the whole village was essentially burnt to the ground.[5] There would be several other instances similar to the two described above and their impact on pacification efforts in the Philippines would have varying degrees of effect.[6]

The battles raged on into the morning of February 5. It was to become what Linn termed as the biggest of the entire Philippine War.[7] The key element to the American victory in Manila was Col. Stotensburg and the 1st Nebraskas securing of Manilas water supply. The attack was launched at ten in the morning on 5 February with the support of the 1st Colorado, a few mountain guns from the Utah Battery and a few captured Nordenfelt artillery pieces. The Volunteers took hill after hill, trench after trench from the enemy.[8] They eventually captured the waterworks building but found that the fleeing insurgents had disassembled the apparatus. However, the missing parts were found hidden in a coal pile. The pumps were soon put into order and running smoothly; Manila now had a secure supply of water, and the army could continue using the capital (Manila) as a showpiece for benevolent assimilation.[9]

The Second Battle of Manila was waged along the aforementioned sixteen-mile American front lines and it involved all or parts of thirteen different U.S. regiments and thousands of Filipinos. American casualty numbers for the conflict report that 194 were wounded and 44 killed, half of whom were Regulars from the 14th Infantry and the 3rd Artillery.[10] Linn suggested that Filipino losses can only be estimated. Official army reports claimed the insurgents suffered four thousand wounded and seven hundred killed.[11] It is difficult to determine exactly how many Filipinos perished, both civilians and combatants. However, news of the Second Battle of Manila finally reached Washington in the days following its completion. The news had stunned the administration. It was largely believed in the capital that the situation in Manila had been cooling.[12] McKinley had recently sent a commission to the Islands to meet with Aguinaldos representatives in a sign of good faith. For that reason, the outbreak of hostilities was emphatically not desired in Washington, not at this particular time and place.[13] Roots comments upon hearing of the news: Our forces were attacked by the Tagalogs, who attempted to take the city.[14] However, despite the grim possibilities that could have occurred, the 8th Corps effectively snuffed out the offensive capacities of the enemy forces on Luzon during the battles of 4-5 February 1899. Aguinaldos Army of Liberation suffered incalculable losses and was now on the run. Gen. Otis would spend the next two years sending columns into the dense hills and jungles of northern Luzon in the chase for Aguinaldo and the ultimate destruction of the Republic.

Gen. Otis dispatched Brig. Gen. Marcus P. Miller of the 1st Separate Brigade to the Visayas on 24 December 1898 with the orders to occupy the port of Iloilo City on the island of Panay. Otis did not anticipate any form of organized resistance and put Miller in command of only the 18th Infantry and Provisional Machine Gun Battery along with the 1st Tennessee. The objective for Miller and his troops would be to peaceably enter the city and lay the groundwork for civil government while maintaining the general order in Iloilos City.[15] However, trouble lay ahead. According to a reconnaissance of the island of Panay prior to the hostilities, it was reported to Otis that insurgent forces had entered the city and formally declared the Federal State of the Visayas which pledged nominal allegiance to Aguinaldos Philippine Republic.[16] It was also estimated that some 19,000 insurgent troops were on the island.[17] Miller took notice and promptly arranged for negotiation with the insurgents. He sought to peacefully transfer to American authority on the island but found out that the insurgent government had no intentions of relinquishing their position in favor of the Americans. It became clear that hostilities would be inevitable.

the Visayas

The Americans initiated hostilities in the Visayas on 11 February 1899 when the U.S. Navy commenced with a naval bombardment of Iloilos City. What occurred next is a matter of dispute between the U.S. Army and the Navy. Each claimed to have captured the city even though it lay in ruins from the bombardments and a series of fires set by fleeing insurgents and residents. Admiral Dewey claimed that naval forces captured, occupied and held the fort and city of Iloilo, and drove the Filipinos out, with absolutely no assistance form the Army.[18] Miller declared that his troops had captured five sixths of the city[19] and that the Army held the main square, all of the trenches surrounding the city and all of the bridges leading in and out of Iloilo. Linn notes that Miller now occupied a burned-out and deserted town, surrounded on three sides by enemy forces and that he was now burdened with the task of rebuilding all public services water, sanitation, trade and government and also deal with a substantial military threat in an effort to combine civil projects with military operations, to find a proper balance of conciliation and coercion.[20]

Miller issued an official proclamation on 21 February 1899. The premise of the decree was the establishment of military government in Iloilo and it was promised that private property was to be respected as well as freedom of religion, the retention of local municipal officials save for misconduct and the opening of the port for trade. Miller proclaimed the Americans have not come to the Island of Panay as conquerors and that the locals need to unite as one people in suppressing crime and lawlessness in the Island.[21] It was also said that a general amnesty would ensue should the insurgents lie down their arms. Millers message was beginning to sink in. Local elites began to recognize that the resistance in and around Iloilos was generally comprised of outside influences, most notably the Tagalogs under the direction of Aguinaldo. By early March of 1899, Miller had set up a thin five mile perimeter around Iloilo.[22]

By mid-March, the situation on the ground was beginning to deteriorate. Guerilla bands roamed the countryside extorting money, kidnapping women, and terrorizing the inhabitants.[23] On 16 March 1899, insurgent Gen. Martin Delgado launched a one thousand man assault on the American perimeter of Iloilo. The lightly defended American garrison near the Iloilo suburb of Jaro was besieged by the insurectos but the 18th Infantry dug in and repelled the onslaught. The waves of bolomen were met by fierce machine gun fire and volley after volley of artillery fire[24]. Delgado and the insurgents quickly retreated to the nearby town of Santa Barbara in an attempt to regroup. However, many of troops sensed the futility of forcibly resisting the Americans. Linn notes that the rebel soldiers quietly returned to their villages and limited their military activity to service in the local militia. Furthermore, this essentially crushed the insurgent offensive capacity on the island of Panay and they would never again try a concerted push to drive the invaders off the island.[25] American casualty figures for the battle stood at one killed and fourteen wounded while the insurgents were believed to have lost at least fifty killed and maybe as high as two hundred[26]. Despite this setback, Delgado and his troops continued to harass Millers perimeters around Iloilo City.

pictured above is a 'bolo' which is very much like a machete. some Filipino soldiers were armed w/ these weapons (and no rifles either). they were famous for charging American lines and being struck down in a hail of gunfire. i even convinced CivArmy1994 to make a 'Boloman' unit for civ3 and he did!

On 5 May 1899, Gen. Otis replaced Miller in favor Brig. Gen. Robert P. Hughes. Otis was insistent upon concentrating the bulk of American manpower in Luzon and around Manila and Miller had petitioned for more troops on several occasions.[27] Thus Hughess task was to root out the remaining resistance on Panay while maintaining the military government and general peace. Linn noted that Hughes went into this task with the mindset that Visayans, in general, were friendly and receptive to the Americans and that the ill will was harbored solely towards the Tagalog sector of the island. Hughes quickly discovered that it was not simply Aguinaldos Republican and Tagalog supporters. It was now becoming clear that Visayans were committed to independence.[28]

Hughes was now becoming more and more frustrated[29] with the unconventional and harassing tactics that the insurrectos were now conducting. For that reason, he set out to completely obliterate the remaining resistance by employing a scorched earth campaign in order to deprive the enemy of sustenance. Search-and-destroy missions were undertaken by Hughess troops in an effort to squash the rebel army in Panay. By August of 1899, the remaining elements of resistance dispersed and Iloilo City was about to receive a significant boost courtesy of Brig. Gen. Hughes.

The key to the pacification and implementation of civic government in Iloilo City rests wholly with the actions of Robert P. Hughes. The total war[30] strategy had compounded the already famine-like conditions that surrounded Iloilo City. The rebel army had already stripped much of the islands livestock, grain and other foodstuffs during the course of resisting the Americans. Hughess aggressive approach simply magnified the dilemma. During the summer of 1899, Hughes cleverly initiated a directive that forbade any and all foodstuffs to leave the city of Iloilos. However, he allowed for the provisions to enter the city. In combination with this, it was directed that any persons living outside the city limits of Iloilo would be subjected to meager daily rations. Delgado, the rebel leader still in nominal control of some portions of the countryside surrounding the port city, denounced Hughess tactics and countered with a blockade of his own for all food coming into the city. It backfired and by mid-August 1899 the conditions of the famine greatly subsided due in large part to Hughess tactics; the citys population had doubled since June 1899.[31]

The next examination is of the island of Negros. This rich sugar-producing island is located in the central Philippines archipelago. The revolutionary sentiments against Spain had arrived quite late on Negros and Linn notes that whatever angst against Spain that existed was restricted to the local levels and that there was no violence or popular participation of Negrenses[32] of the Spanish who departed the island for good on November 22, 1898. However, a flurry of political activities quickly ensued. Aguinaldo promptly claimed Negros as part of the newly created Philippine Republic. The Federal State of the Visayas, those who pledged only nominal allegiance to Aguinaldos Republic, also claimed the island. The dilemma became a bit more complicated when the inhabitants of Negros shunned both claimants and officially declared two separate states. El Gobierno Republicano Federal de Canton de Ysla de Negros (The Federal Republican Government of the Canton of Negros Island), which consisted of Negros Occidental, and La Republica Federal Filipina del Canton de Ysla de Negros Oriental (The Federal Philippine Republic of the Canton of Negros Island Oriental) declared shortly thereafter their independence from both Spain and Aguinaldos Republic. Both Negros Occidental and Negros Oriental did not prefer Aguinaldos rigid, centralized set-up for the Republic and the Negrenses sought a more autonomous and decentralized format. Prior to the American-Philippine hostilities, the Negros Occidental contingent petitioned the Americans for a protectorate status. It was promptly rebuffed.[33] Shortly afterwards, Aniceto Lascon, the first president of Negros Occidental, unfurled an American flag in Bacolod as a sign of peace. He also sent a petition to Gen. Otis highlighting the desires for American protection.[34] There appears to have been a certain amount of uncertainty in the American military command regarding this offer. However, by March of 1899, Otis had no choice but to accept the offer from the Negrenses in lieu of the recently initiated hostilities in Manila. For that reason, Gen. James F. Smith was appointed as military governor of the new Sub-District of Negros, part of the new Visayan Military District. A four hundred man force was deployed under the command of the 1st California and Maj. Hugh T. Sime.

map showing location of the island of Negros

James F. Smith is an interesting study. Linn described him as an experienced politico who had close ties with Gen. Otis and that he avowed the concept of benevolent assimilation. Furthermore, Smith is said to have had a great interest in humanitarian endeavors and that he had a particular interest in political issues.[35] He arrived in Bacolod on March 4, 1899 and his immediate tasks as military governor was to control customs and trade, communications and the police.[36] Smiths situation in Negros differed greatly from that of his peers insomuch that resistance did not initially exist upon the arrival of the Americans. For that reason, a direct route towards civil government was in the offering. Smith promptly left the day-to-day business of local government in the hands of the locals, or at least the wealthy pro-American Negrenses.[37] This expedited pace of pacification and installation of civil government allowed Smith to form a Negrense delegation in order to attempt to adopt a local constitution. However, as Linn noted, it exploded into factional battles and any such consensus on a constitution would have to wait.[38] Frustrated by the non-consensus, Smith re-organized the format of the local governments and essentially stripped them of most of their municipal authority. Instead, Smith redefined their roles as an advisory council in support of American military governance with an eye on a much broader and inclusive local governmental structure. Its participants would be decided in local elections slated for October 1899.[39] In the meantime, Smith insisted that the 1st California do nothing to disturb the harmonious relations with the public. In order to facilitate this, Smith established a list of prices for goods and services a dozen eggs for a quarter, twenty cigarettes for a nickel so as to nip any potential conflicts between soldiers and the local merchants in the bud.[40] This, in effect, defused any potential tensions in the market districts of Bacolod and at the same time, stabilized the local economic markets.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Linn, The Philippine War 1899-1902, 42. It is noted that Filipino accounts center on the unnecessary provocation by the American sentries. American accounts claim that armed insurgents were seen scurrying about the Manila suburb. The darkness and the seemingly chaotic and unorganized nature of the conflict surely complicates the matter.

[2] Linn, The Philippine War, 44. Linn noted that the defensive troop formations in and around Manila was a most precarious position to be in and that the 1st Nebraska, at the extreme eastern point of the lines, suffered from an extreme vulnerability to being cut off or surrounded by the enemy.

[3] Linn, The Philippine War, 47.

[4] Linn, The Philippine War, 47. Linn: Suppression of the Manila disturbances was a crucial, if often overlooked, part of the battle of 4-5 February. Furthermore, the Guards prompt action secured the city and prevented the terrifying prospect of the 8th Corps facing attack in all directions.

[5] Linn, The Philippine War, 50.

[6] See Linn, The Philippine War, pp. 42-64.

[7] Linn, The Philippine War, 52.

[8] Quoted in Linn, The Philippine War, 56.

[9] Linn, The Philippine War, 57-58.

[10] Linn, The Philippine War, 52.

[11] Linn, The Philippine War, 52.

[12] Linn, The Philippine War, 54.

[13] Linn, The Philippine War, 55.

[14] Quoted in Linn, The Philippine War, 52.

[15] Linn, The Philippine War, 38. The author notes that Otis gave extensive instructions for setting up a military government in Iloilos City.

[16] Linn, The Philippine War, 38. The newly arranged Visayan state had a government that was composed primarily of wealthy and influential Panayans and nothing else thus leaving one ethnic group in charge of the entire island chain of the Visayas. They recognized Aguinaldos Republic but refused to forward taxes and sought to pursue independent policies. This caused a certain amount of friction between the two sides. Some wanted to dig in a fight while other pleaded for a peaceful transition. Others were adamant and promised that theyd burn the city upon the arrival of American troops.

[17] Linn, The Philippine War, 38. According to Linn, an estimated 4,000 tiradors (riflemen), 14,000 macheteros (bolomen machete-wielding infantry) and an additional 1,000 to 1,500 crack troops sent from Luzon under the direction of Aguinaldo.

[18] Quoted in Linn, The Philippine War, 68.

[19] Quoted in Linn, The Philippine War, 68.

[20] Linn, The Philippine War, 69.

[21] Quoted in Linn, The Philippine War, 69.

[22] Linn, The Philippine War, 70.

[23] Linn, The Philippine War, 70.

[24] Linn, The Philippine War, 70. It is stated that approximately three quarters of all the insurgent attackers were bolomen. Linn also notes that the rebel officers convinced the machete-wielding infantry that the American soldiers would simply flee upon sight of the bolos!

[25] Linn, The Philippine War, 70.

[26] Linn, The Philippine War, 70.

[27] Linn, The Philippine War, 71-72.

[28] Linn, The Philippine War, 72. Numerous Iloilo elites presented evidence to suggest that they wanted no part of American rule and instead preferred complete autonomy.

[29] Linn, The Philippine War, 72.

[30] This is a direct reference to William T. Shermans concept of scorched earth or total war in that the intention is to deny the enemy of any and all means of sustenance. For more on total war see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_war.

[31] Linn, The Philippine War, 73.

[32] Linn, The Philippine War, 75.

[33] Linn, The Philippine War, 75. It is noted that Captain Henry Glass of the USS Charleston was approached on 12 November 1898 by the leaders in Bacolod regarding the possibility of an American protectorate in Negros Occidental. Glass deferred on the grounds that Otis and the McKinley Administration had yet to set the official policy for the Islands.

[34] Linn, The Philippine War, 75.

[35] Linn, The Philippine War, 76.

[36] Linn, The Philippine War, 76.

[37] Linn, The Philippine War, 76.

[38] Linn, The Philippine War, 76.

[39] Linn, The Philippine War, 76. Smith was apparently fed up with the grid-lock that the native legislative body had created within the Balocod.

[40] Linn, The Philippine War, 76.

Real fighting men of character appreciate a good man, even if he comes from the opposing side.

Real fighting men of character appreciate a good man, even if he comes from the opposing side.

The "system" edited the Washington Post.

The "system" edited the Washington Post.