Harvin87

The Youth

Hermann Kriebal spoke those as the last words of the German commission to surrender to the Allies at the end of World War I.

Hehe.. that sounded like a football match ... "see you on sunday" ....

Hermann Kriebal spoke those as the last words of the German commission to surrender to the Allies at the end of World War I.

H. Morgenthau about his talk with Arthur Zimmerman in Berlin, 1916, according to his book published in 1918.after the war, he said, they (Jews) are going to be much better treated in Germany than they were before

It's just so ironic, sad and funny at the same time.

I don't know much about anti-Semitism immediately after the war, but I'm guessing that he was actually right until 1933. Weimar Germany was very socially liberal system, so there probably wouldn't have been much (or any more than people) discrimination against Jewish people until Hitler started changing things.

But was that any worse that before the end of the war?

Hmmm. No, that's not exactly true. Hitler didn't just show up in '33 and change (or capitalize on a change in) German society. These things had been developing for quite some time. Pretty much since the end of WW1; the stab-in-the-back legend had always blamed "the Jews" (primarily because some of the more notable Spartacists and other revolutionary groups happened to be Jewish, for instance, Rosa Luxembourg) and anti-semitism was quite widespread in the Freikorps movement.

Germany was a divided society prior to Hitler's rise; the liberals certainly had the upper hand throughout the 20s, dominating the public sphere and most social discourse, but that's not to say that these sentiments weren't held by a signifigant minority through the same period. Hitler was, at best, a catalyst that transformed these elements and brought them to power. He didn't create them, nor were they new.

Oh, I don't disagree at all - but, just as you say (bolded above), the anti-Semites were a minority. There are anti-Semites around today, too, in Germany just as in other countries

No. Not right away, at least. Eventually it was. The Dolchstoßlegende was the foundation upon which the anti-semitism of Nazi Germany evolved. It didn't come from the sort of garden-variety anti-semitism born of general regressive forces, that you might find in Britain or the US or anywhere else at that time. German anti-semitism took on a special character after the war, because it was the Jews who were blamed by the right for the defeat of Germany.

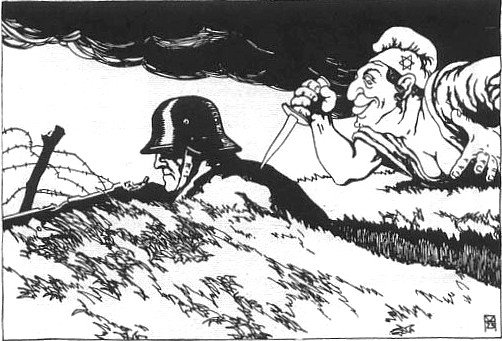

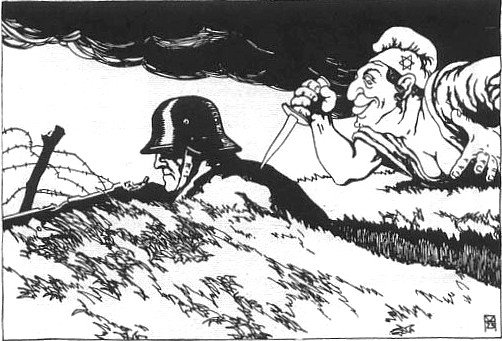

This cartoon, printed in 1919, pretty much sums up how the right was seeing Jews after the war, and throughout the Weimar period:

The right was largely discredited after the war, but as we all know, the pendulum eventually swung back. Unfortunately, the Weimar centrists were unable to contain the radical elements of the right as well as they were able to contain the Spartacists and other radicals of the left. But it wasn't like they could incite the Freikorps to assassinate Hitler, as they did with Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknicht. They had a falling out over the Kapp Putsch, plus, most of the Freikorps had joined the SA.

Yeah, the extreme right was always going to persecute the Jews with their fanciful escapism from the truth, but that had not particularly changed from during the war, when Jews were similarly persecuted.

The Kapp Putsch shows the lack of support by the government of the extreme right and vise versa.

No, it had changed quite a bit from before the war. Anti-semites in other countries didn't have the stab-in-back-legend, which fundamentally changes the character of the anti-semitism and creates the possibility of it becoming a popular sentiment in that society ... which eventually happened.

The right that had been in power before the war didn't set up death camps or institutionalize extraordinarily extreme persecution of the Jews. They taunted them, treated them as second class, threw some Kafkaesque red tape their way - that's about it. Even before the Weimars, Germany was a better place for a Jew than many other places in Europe (France comes to mind). The right that got into power 20 years after the war was a little different than the one that had been around before the war.

The Kapp Putsch shows that the Weimars couldn't keep their attack dogs on a short leash anymore; the Freikorps had begun to get unmanageable, a portent of things to come.