Here is the full-length first instalment of the History of Lyne (up to c. 1000 BN). All this is subject to change, and is merely the first draft. I welcome any comments; there will be no radical changes to this, but it will almost certainly change in small ways here or there whatever anyone else says. If I edit, I will edit in red here and I will post the whole thing again when it is all complete. As I continue this history, I will edit this post rather than posting new posts, because I may do it in relatively small chunks.

Lyne is an ancient kingdom; perhaps it has the longest recorded history in the world. Dozens of dynasties have fallen and risen over Lyne, and it is by these that Lyne’s history is recalled: the dynasties are numbered and named, and every educated Lyni knows the deeds and works of each Royal House from back to front.

People lived in Lyne eight thousand years ago, but they were not Lyni; they were barbarians from the north on the fringes of even their own civilisation (migration no. 1). They were the children of the god Replesit, but he was cast from heaven by his cousins and cast into the sea. The cousins were many in number, and they have ruled the world ever since. The Lyni were their descendants, and they came from the west (migration no. 3), and ejected the Replesians, who fled back into the north, where they had come from.

The Lyni were of the same stock as the pre-Avardians, and the differences were not more than regional ones until the third millennium BN, when the pre-Avardians were displaced by invaders from the central sea. They pushed the pre-Avardians into Lyne, and they mingled and became as one people. Their gods became one pantheon, and this pantheon was thoroughly established by 2

800 BN. Leore became a centre of religion at this time, and the main city was ruled by a theocracy, known to history as the First and Second Dynasties.

The influx of Pre-Avardians around this time sped up the urbanisation of Lyne further, and, in the area around Leore, kingdoms began to emerge around urban centres, and Lyne was the most important of these, based around Leore itself, which had always been an important religious centre for the worship of not a particular god, but rather a particular selection out of the many gods. Lyne was a fairly centralised despotism by 2

500 BN, with a well-recognised monarch, the Lere. The Third Dynasty began at this time, and the rule of the Lere was secular, with religious matters being referred to the priesthood.

There were other kingdoms all around, and it is an interesting topic for the study of modern classicists, but this is an era where little of the cultures of the surrounding kingdoms is known. It was quite similar, but there were differences too. One legend says that in the old Oxperit kingdom the people were mostly cannibals. Anyway, the Oxperiti were the first to be defeated in battle and subjugated rather quickly in 2354 BC after a long siege of their capital. However, that wasn’t the end of that, because they rebelled several times, resulting in the thirty-year long Oxperit war (2

320-2

289) before Leore City was sacked by Jityli soldiers sent to intervene on the Oxperiti’s behalf. After this, there was an eighteen-month period of bankruptcy and rioting under an Oxperit-imposed tyranny (2

289-2

287) before the tyrant, Ipe, was ejected by the mob, resulting in a brief period of something that might be called democracy but might better be called chaos.

The next twenty years were spent in a state of anti-Oxperit paranoia, and this culminated in the restoration tyrant’s son, Peregrit, by Oxperiti arms in 2

264. He finally crushed resistance in Leore City and, with a few supporters, seized a large silver mine, and used it to fund his expansion of control over the area. He encouraged trade, and the city grew, and he subdued the rest of Leore and parcelled its land out to his supporters.

His son Opite succeeded him in 2234, and he campaigned into Jityle and received its ruler’s submission and married his heiress, before declaring himself Lere Lerype (King of Kings). This, not unnaturally, evoked the ire of Oxperit, which again crushed the Leori armies in battle several times before being caught in an ambush. With the support of Jityle,

Opite managed to defeat Oxperit in a long campaign, and subdued Oxperit fully by

2190, before murdering his father-in-law and pressing the Jityli contingent into his service by decimating it. He marched straight east and took over Jityle before anything could stop him.

Lyne’s future was, perhaps, only safeguarded by the fact that he chose that moment to die, before he had had a chance to have any heirs, because this allowed a minor ruler from a small area of Jityle (dark green), who had sent a small contingent to

Opite’s army and accompanied it himself, to declare himself King, beginning the Fifth Dynasty in 2

185. The army, seeing no better candidate, went along with this reasonably quietly, and thus king Leple started his dynasty.

Leple

and his son, Leple II, were extravagant ruler

s, and

their reigns involved the building of numerous palaces which dominate the Old City of Leore to this day. It was partly this extravagance and his setting up of a new tax system that meant that Lyne broke into civil war again, but throughout the

intermittent civil war lasting for

eighty-two years (2118-2036), the conflict was kept relatively small-scale, and the Leplids always retained control of their capital, and found the funds here and there to aggrandise it still further. They eventually won by recruiting large numbers of auxiliaries from the desert and peasants from Lyne itself, who, immediately after their conclusive victory against the opposing Tyrid dynasty in

2036, rebelled and expelled the Leplids from the capital and set up a government along the lines of a tribal council. However, by recruiting the remains of the Tyrid armies, the Leplids were eventually able to besiege Leore, but once again, their troops ran riot, and, while they had managed to reaffirm their control of Lyne by the end of the

century, Leore City was gutted and the capital was moved to their fortress near the river-mouth at what is now the city of Rityre (the strategic centre on the political map).

Much of the next century was spent on subduing rebel remnants and bringing the country back under central control. A highly effective military machine was constructed, which managed to conquer the last two independent principalities in Jityle. At any rate, Lyne was pretty much pacified and

large revenues were beginning to flow into the King’s coffers again when Uplerit, the dominant warlord of Milene and a renowned military leader, invaded with a huge army in

1935.

The Old Kingdoms of Lyne.

It was on the occasion of Uplerit’s first incursion when it was first found that Lyne’s financial system was utterly inadequate. The decision was made to bribe the invaders to leave, and an extraordinary tax was levied for the purpose, but this highlighted the increased need for the bureaucracy that was presently insufficient for purpose and housed in the Temples to the various gods. The gods’ shrines were plundered by the Lyni to save them from their oncoming plunder by the southerners. Clearly, this was no solution, so new methods had to be found, and the way forward was simply to make taxation a sacred matter: the Temples’ resources were the Treasury, and they had the power to collect at will. This gave them great power, but they banded together and the solution worked admirably. With the populace in a state of panic about what would happen next time Uplerit invaded, the Temples gained riches and each began to specialise in a certain type of government business, only partly dependent on the previous significance of the god in question. The war with Uplerit signalled a great increase in the number of Lyni war gods, and these war gods’ identities were gradually merged as Lyne’s military establishment became more refined over future centuries.

Temple guards were gathered in huge numbers; enormous wealth was invested in shields and armour (but this all went to the Temples because many of the armouries were attached to particular Temples) and a huge army was constructed to wage a long, existential campaign against Uplerit from 1931 all the way up to 1905, in the course of which Uplerit lay siege to and conquered both Old Leore City and Rityre before being outmanoeuvred, deprived of supplies, and his army was almost annihilated in a series of ambushes in Jityle. The army’s general, Tsilie, riding on a wave of enthusiasm from his troops, marched his army to Rityre and was crowned King in spite of the Leplid who was supposedly ruling, founding the Sixth (Tsiliad) Dynasty in 1904. Uplerit’s realm fragmented, and Tsilie received the submission of the Mileni princes one by one after his son, Tsilipit, marched south and set himself up as a sub-king in the most powerful of the principalities. He also enforced a rota-principality system for the other six Mileni principalities; this kept them in line admirably well, especially as the lowest position on the rota was attendance at the royal court in Rityre.

This war clearly revolutionised Lyne and it would never be the same again. The south was conquered and well-administered as a practice-kingdom for the eldest son of the King, with the other princes on an enforced rota. The civil service-cum-religious establishment had proved itself extremely efficient, and there was healthy competition between the Temples in the raising of funds and dealing with problems in local government as they arose.

However, the division of the country into temple-districts and temple-units which possessed far more power than the central government merely led to the development of anarchy in Lyne. The Mileni principalities were far calmer than the Lyni heartland for the next century as the Temples competed, at times violently, over their lands, and this was exacerbated during the first decades of the century by the large numbers of soldiers in the service of the Temples, who were unwilling to be disbanded. Instead, they fought and in each town the multitude of Temples was shortly reduced to a single one in each. The Tsiliads were utterly inept at stopping the chaos, and, after enduring a few decades of it, they gave up and left properly for Milene, which was not in such a state of chaos, in 1877.

In the end, the previously extensive Pantheon was reduced to six gods while the rest were ignored and largely forgotten from then on, and only one god was normally worshipped in each town, although the others’ existence was not denied. In the largest cities alone were multiple Temples to be found, and in the capital the six Temples each housed a division of the bureaucracy. These gods were Sinclarit, Otsulit, Arare, Minit, Emplerude, and Neplit. The Otsulitists came off best after the half-century of chaos that ended in 1849, and they nominated as a king a certain Lorepode (numbered as the Seventh Dynasty), who, after a few years of restless peace, set off for Milene in 1842 with insufficient force to defeat Tsilie IV, and was consequently defeated and killed in the following year. Tsilie marched east with a larger army, and was opposed by equally large armies from all the Temples. The warlords fought each other and Tsilie until eventually a warlord called Mereciane came out on top, defeating his last opposition in 1812, and coming to terms with Tsilie V who was left in power in Milene. He founded the Merecianid (Eighth) Dynasty, and in this period the corruption in the war-exhausted Temples was largely ironed out, so that, despite a few rebellions, the Merecianid era was one where the religious bureaucrats actually served as royal deputies rather than troublemakers.

The Merecianids, then, achieved internal security for the most part, and could concentrate on the integration and expansion of their realm. Mereciane’s first acts were with regard to Jityle, which was overly sectionalist, and which was not as fully integrated into the Temple system as Leore was. He crushed the last barriers that defined the old kingdoms and generally expanded the power of Neplitism over the area. Neplitism was by far the most evangelical cult, even if it was not the largest, and so it dominated Jityle relatively easily, and the Neplitist Temple in Rityre was, after all, the main royal treasury. In fact, the treasury moved out of the capital into Majute, the city in Jityle that is the capital to-day, in 1752.

The Merecianids also had to deal with Milene, and they did so at great length and with great difficulty. When Tsilie VI died in 1761, it was decided to replace him with the heir apparent to the throne of Lyne, as had been practised under the previous Tsiliads. However, this caused a long war with between the two dynasties, and the rota princes, who had come to respect the Tsiliads highly, had to be dealt with individually. It was a difficult and acrimonious process, and, in 1743 a Tsiliad army managed to raid and inflict significant damage on Oxperit, causing widespread panic there and a mutiny. Faced with a very real possibility of total defeat, the Merecianid king withdrew and made peace.

Reforms to the system were made and the army was restructured before another invasion was made into Milene, which actually managed to defeat the Tsiliads fully in the years 1723-1711. The Temple system was imposed on the Tsiliad demesne land by the end of the century, and the rota princes in the outlying areas of the region were subdued over the first decades of the next century, although not without resistance, and Temples were installed there too.

Stability, then, had come to Lyne at last, and the Kings became increasingly tied into the administration of the kingdom and less and less bothered with military and external matters. Milene gradually became more peaceful and more integrated, and largely adopted a combination of Emplerudism and Ararism. Lyne remained at peace and stable for a remarkably long period of time, although there were occasional raids and rebellions here and there. However, this ended with a series of incidents on the northern border with the petty rulers of Micit, and these incidents were blown up beyond proportion because there was a regency in Lyne, which meant that the regents were exceedingly eager to defend Lyne on any and every basis, especially as their charge was very near adulthood but they wanted to maintain their power anyway. The regents sent the King and his army into Micit in 1592, where they were dealt a significant defeat by the more battle-hardened Miciti. It was a difficult struggle for Lyne, but one that it ultimately won simply by being able to recruit more men than the Miciti princes could, even if the Lyni troops were generally worse, having been at peace, apart from a few minor rebellions and raids, continuously for the last century.

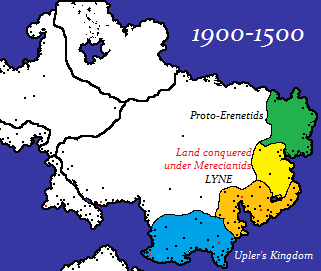

The next century contained a series of campaigns to subdue the north, featuring increasing overexpansion the further north the Lyni armies got. By 1540, the Merecianids had subdued a large area to the north, but were meeting with far fiercer opposition, and in the end, a series of Merecianid armies were defeated by an alliance of the three northern dynasties who ruled kingdoms of semi-nomads, the Erenetids, Pleporitids, and Lycorids, and a huge army of northerners with a large number of cavalrymen went on a terrifying rampage into Lyne. The Erenetids seized the throne and wreaked terrible destruction on most of the major cities and crushed all resistance mercilessly, establishing the Ninth Dynasty in the 1520s, whereupon the Lyni Temples (except the Otsulitists who were mostly massacred or converted on this very pretext that they didn’t) allied with the Pleporitids and fought another large-scale civil war, which ended with a Pleporitid victory in 1496.

However, the Pleporitid apparent triumph and the coronation of the first ruler of the Tenth Dynasty was not as conclusive as it might have seemed, because the Lyni were not content to be ruled by any barbarian, and there were numerous Erenetid regiments still freely plundering the countryside, and there were even more Lycorid forces; the Lycorids were beginning to set themselves up in Jityle as an independent principality.

This shortly caused the effective breakup of the Lyni state for the next century and a half into four warring states, namely the Pleporitid state in Leore, the Lycorid state in western Jityle, the Erenetids in Milene, and a Neplitist theocracy running parallel to that and also ruling over Jityle and Micit and recognising the Erenetid king. The Lycorids and Neplitists, however, remained largely peaceable towards each other, and the Neplitists even supported the Lycorids against the Pleporitids until about 1440, and the Erenetids were largely peaceful during this time too. The Neplitists concentrated all their energy and resources into centralising Micit and the North into their theocratic state, and, when this was done, they moved to do the same to the Lycorids, and fought a long war over it. Meanwhile, the Erenetids finally defeated the Pleporitids by 1420, and reinstated themselves in the capital. The Erenetid monarch became a Neplitist himself, and the Neplitist and Erenetid states united, crushing the Lycorids between them.

However, in this arrangement, where the Erenetid King was little but a foreign figurehead superimposed on a bureaucracy that had quite a mind of its own, the Nepleone-Porit was by far the greater figure. The Erenetids wished to reconquer their homeland to the north, and in return for the allocation of funds for the purpose, the Nepleonids (who were already being sarcastically called the “Eleventh Dynasty” by contemporary observers) alienated more and more royal prerogatives and established control over the other Temples as well as the Neplitist ones, and the King’s long absences on campaign helped with this too. Soon enough, the Erenetid king had conquered the north, and he held his capital there for several years while he crushed resistance.

The Neplitists, then, used the opportunity to grab a few more converts, and to use their influence to found cities of Lyni colonists and missionaries in the north. Some of their efforts were successes, and they form some of the biggest cities in Juplene to-day. Nevertheless, they met considerable resistance from the local princes, and, in the end, the Erenetid monarch decided that the Neplitists were undermining his authority in his kingdom in the north and had to be expelled. Unsurprisingly, the Nepleone-Porit merely declared him a heretic and deposed him, to great acclaim from most Lyni, and sent an army north, which, with ample support from the Lyni colonists, who were already numerous, defeated and killed the last Erenetid in battle in 1357. Juplene was now annexed, and the Nepleone-Porit staged a great triumph and coronation in Majute, where he was crowned Oristare (Emperor) with great pomp. The monarchy continued, invested in a Merecianid who had a very specious connection with the original dynasty, but whatever powers it still possessed were gradually taken away until it was finally abolished in 1267.

Summary of Lyne’s governmental system (partly for Masada's use): So, then, Lyne’s system of government was firmly crystallised into the ideal that would be varied upon, but never supplanted, for the next millennium and a half. Local government was in the hands of a particular Temple, and the cult of the Temple depended on the region: most of the outlying regions were in the hands of Neplitist Temples. Ministerial government was also in the hands of particular Temples, although the allocation of funds was similarly in Neplitist hands, rendering them more powerful than the other Temples. This bureaucracy was headed by the various Poriti (High Priests) who were all subordinate to the Nepleone-Porit (High Priest of Neplit). In theory, there was a position of Lere (King) but it had lapsed by now, mostly because it was largely powerless because all the power was in the hands of the bureaucracy anyway, and this was formalised by the coronation of the Nepleone-Porit as Oristare (Emperor) and the declaration that Lyne was an Empire (Oristate), which vested full authority in the Nepleone-Porit, although this authority was limited by the power of the bureaucracy and the power of the other parts of the bureaucracy to disobey the Emperor, who, while he may have been supreme commander and ruler on foreign matters as Oristare and supreme Chancellor as Nepleone-Porit, he had no theoretical authority to do anything that did not fall within those spheres. For instance, he could not summon an army without the command being passed down through the Sinclaritist hierarchy first.

Of course, under this, there is a land-owning aristocracy, especially in the countryside; the Temples do not actually own enormous areas of land, and their authority runs parallel and sometimes in competition with the aristocrats.

In the next few centuries, the Merecianids conducted extensive expansion into the interior and along the northern coast, a coast that was inhabited by peoples who were a combination of Erenetid and Messadi elements. Here, they supported Erenetid chieftains (this was what the Merecianids have always called the northerners; they have never distinguished them from the Erenetid dynasty in Lyne) against their Messadi counterparts, precipitating large-scale conflict in the area throughout the latter part of the period. Lyni military camps became permanent, increasingly, and as hatred grew and Messadi raids and Lyni missionaries came into the area, they grew into major towns. The Messadi were driven into the desert by 1040, generally speaking, after a good century of resistance and raids.

Meanwhile, in the west, the Merecianids pursued a more direct approach, subduing various domains separately, and adding them to the Imperial demesne. Several towns along the coast of Jilpe became, thus, royal towns, and a few new towns were founded in the interior. Land that was not tremendously suitable for cultivation and civilisation had attempts to be cultivated and civilised on it, and the Merecianids’ efforts mostly failed in their ambitious goal to bring huge amounts of Eglante into direct Imperial rule quickly. However, perseverance eventually meant that Eglante was more or less owned directly by the Emperor by the end of the period, again at the expense of numerous prosperous Messadi tribes who were driven out of the few fertile valleys of Eglante, and eventually out of all Eglante by 950.

The war against the Messadi, then, was originally motivated by the desire to increase the power of the crown over the aristocracy and the Temples, but, ostensibly, it was for the prevention of raids, and it was a crusade against a heretical cult. Of course, the Emperor was, in fact, the High Priest of Neplit, but he used the conquests to limit the power of his own Temple, which was, without doubt, the most powerful entity in the country. He did this by granting privileges to evangelise in Eglante, Jilpe, and in the far north, to the worshippers of Emplerude, and he granted them funds. The Neplitist establishment was, of course, highly dismayed, and while it did not try to monopolise evangelism while this pro-Emplerudist policy was being carried out in the 1200s and 1100s in the north, the Neplitists used their own resources to convert equally many Erenetid and Messadi chieftains.

When the Emperor began to repeat his predecessors’ policy in Eglante in about 1050, it proved too much for the Neplitists, not to mention the fact that the Neplitists and Emplerudists in the north had deviated somewhat from their homeland’s religion and had developed something of a frontier culture, but, in terms of doctrine, they had moved in somewhat opposite directions. At any rate, the Neplitist and Emplerudist towns and Erenetid chiefdoms in the north and across the borderlands all the way to Eglante fought a long war, which was tenuously connected to a series of rebellions in the lower echelons of the Neplitist hierarchy, and the Emplerudists eventually came out on top, because they had, with Imperial backing, been stronger in the first place. In the end, though, the Neplitists continued to dominate many areas in the north, because the war ended with a peace imposed by the Emperor by force in 1009.

Thus, then, was the position when the Messadi attacked in large numbers in 1005, and they were repulsed by the ingenious tactics of experienced generals who had just spent their lives fighting each other. Dealt a sound hiding, the Messadi went away and

migrations started at this point, particularly, that would set off the chain of events that resulted in the huge Messadi empire that would conquer much of the continent.