You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The European Project: the future of the EU.

- Thread starter Hrothbern

- Start date

Eu helps us not have to worry about money.

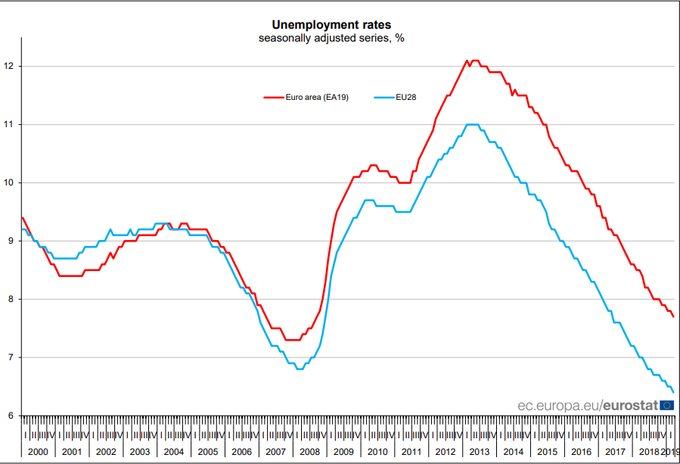

Don't worry. That blue color of the employment graph will spread southward.

This last 7 year budget period East Europe did very, very well in utilising the unrestricted access to the Single market of old EU while having new investments equipment + much lower labor cost, to boost its intra-EU export economy. (an advantage third countries, or simple Custom Union members, outside the Single Market never get). It has hit a bit the job growth of the old EU (Macron complaining and coming with statements on EU reforms to lower that competition), but it went all in all fairly well.

=> East Europe is up and running. Won't be stopped anymore in its catch up.

For the new 7 year budget period there will be more attention (and money) for the South European countries. Getting more jobs there.

Labor mobility from South to North will help there (job market in the North and East will get overheated).

Prime the pump.

Last edited:

Patine

Deity

- Joined

- Feb 14, 2011

- Messages

- 12,041

A lot of news currently ofc on the EU parliament election of May 23-26.

Here a list of posts from the Business Live feed of the Guardian on the Q1 2019 GDP and unemployment expectations for EU countries.

Unemployment at its lowest % since 2000, and for the EU-28 even lower than the booming years 2007-2008. Current rate 1% less per year.

What I understand is that special funds will be raised in the coming 5 year period to tackle the high unemployment rate in some regions in South Europe. Spain doing on its own already quite good.

It is not as strong as for example the US, not as spectactular as underdeveloped countries picking up... but all in all a fair perspective for the elections.

The only bad news is that it will strenghten the Euro somewhat.

View attachment 523868 View attachment 523869

Why are Turkey, Serbia, Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland on that map if it's statistics of EU members?

Why are Turkey, Serbia, Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland on that map if it's statistics of EU members?

It is first of all practical to add those numbers when it is about unemployment because of labor mobility. Certainly for Norway, Switzerland and Iceland who are in the EFTA.

And I must say that I really dislike it when for example Norway is shown as a grey area for all kinds of EU statistics. After all Norway is (for me) part of the family.

In the dawn of the EU.... there was Spel Zonder Grenzen, Jeux Sans Frontières, It's a Knock-out, Spiel ohne Grenzen, Giochi senza Frontiere

It started in 1965

And in homage to Jacques Revaux who wrote the music for the TV series Jeux Sans Frontières, sung by who else than Mireille Matthieu (how lovely chaotic).

In the time that French was still seen as genuine culture here in NL (I had to learn French at primary school... not that it did help much)

But it did help loving French chansons

And in homage to Jacques Revaux who wrote the music for the TV series Jeux Sans Frontières, sung by who else than Mireille Matthieu (how lovely chaotic).

In the time that French was still seen as genuine culture here in NL (I had to learn French at primary school... not that it did help much)

But it did help loving French chansons

I grew up watching Its a Knockout and Jeux Sans Frontieres although like Eurovision we didn't do very well at them, perhaps why we maintained everyone else took them much too seriously

Cheetah

Deity

Just for completeness' sake, I would say. Turkey is partly in the Customs Union, Serbia is an aspiring member, and Norway and Iceland are members of EFTA and the Single Market. Switzerland is an EFTA member, and has signed (but not ratified) the EEA agreement.Why are Turkey, Serbia, Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland on that map if it's statistics of EU members?

In the dawn of the EU.... there was Spel Zonder Grenzen, Jeux Sans Frontières, It's a Knock-out, Spiel ohne Grenzen, Giochi senza Frontiere

It started in 1965

I don't think anyone should mourn the demise of "Games without frontiers". I mean... WTH was it even there?

I don't think anyone should mourn the demise of "Games without frontiers". I mean... WTH was it even there?

European nostalgia

You really miss an elementary part of historic awareness !

That piece of music and that black-white TV picture at the start... that was also there when international European wide broadcasts were there on for example football. The Champions Leagues, etc.

For my generation that music and picture is of iconic European value already.

And then those games.

We had in NL the same games between cities, and everybody who could watch, watched, the whole family together... and perhaps even with some cola or fanta with chips (the plain salted ones.. even paprika (bell pepper) chips had to be invented yet).

And instead of ideological nationalism, we were all immersed in our bias for our cities or our countries. Looking at often hopelessly failing representatives slippering over soap, in water, etc.

It was all new !

EnglishEdward

Deity

Yes, I remember watching Jeux Sans Frontieres when I was a growing lad.

Its manifestation in the UK was presented by the infamous Eddie Waring.

It was the highlight of European Civilisation, although at that age I thought that

adding an alligator or two to the water would have made it more interesting.

Been downhill ever since.

Its manifestation in the UK was presented by the infamous Eddie Waring.

It was the highlight of European Civilisation, although at that age I thought that

adding an alligator or two to the water would have made it more interesting.

Been downhill ever since.

Ferocitus

Deity

NSFW and a choking hazard for those having Doritos for breakfast while watching Judge Judy.

innonimatu

the resident Cassandra

- Joined

- Dec 4, 2006

- Messages

- 15,377

Update on how the EU creates "government by corporations": CETA's "investment courts" were declared legal by the ECJ. ISDS had become a dirty word, so the EU created the "Investment Court System" to be essentially the same thing, only under a different name and whitewashed, as per the drunkard-in-chief's declarations here.

It fully remains about "measures to protect foreign investments and investors". Including the non-foreign "investors" who set up convenient "foreign" corporations. Investor is kind of a citizen with more rights, an upper caste, you see...

Keep in mind that this would not exist without the EU. When they spew their propaganda about "social Europe" and "democratic accountability".

On the issue of democratic accountability, keep in mind especially that the commission declared CETA in force even despite most countries not having yet ratified it.

It fully remains about "measures to protect foreign investments and investors". Including the non-foreign "investors" who set up convenient "foreign" corporations. Investor is kind of a citizen with more rights, an upper caste, you see...

Keep in mind that this would not exist without the EU. When they spew their propaganda about "social Europe" and "democratic accountability".

On the issue of democratic accountability, keep in mind especially that the commission declared CETA in force even despite most countries not having yet ratified it.

Last edited:

Patine

Deity

- Joined

- Feb 14, 2011

- Messages

- 12,041

Update on how the EU creates "government by corporations": CETA's "investment courts" were declared legal by the ECJ. ISDS had become a dirty word, so the EU created the "Investment Court System" to be essentially the same thing, only under a different name and whitewashed, as per the drunkard-in-chief's declarations here.

It fully remains about "measures to protect foreign investments and investors". Including the non-foreign "investors" who set up convenient "foreign" corporations. Investor is kind of a citizen with more rights, an upper caste, you see...

Keep in mind that this would not exist without the EU. When they spew their propaganda about "social Europe" and "democratic accountability".

On the issue of democratic accountability, keep in mind especially that the commission declared CETA in force even despite most countries not having yet ratified it.

This sounds like how the Mega-Corps (most of which were centred in Japan) created, ran, and administered national governments all over the world in the corporatist-dictatorship-oriented dystopian science fiction series "Cyberpunk 2020," from back in the '80's.

innonimatu

the resident Cassandra

- Joined

- Dec 4, 2006

- Messages

- 15,377

And another example of EU institutional corporatocracy at work: EU court advisor sides with Airbnb against French restrictions

The European Court of Justice Advocate General submitted an opinion Tuesday siding with Airbnb in a case challenging strict French rules.

The Prosecutor’s Office in Paris France filed an indictment for infringement of Hoguet law (real estate law) concerning real estate agents against Airbnb Ireland. Airbnb Ireland denies acting as a real estate agent and the Court of Justice agreed. The opinion found that Airbnb services fall within the scope of “information society services.” The AG rejected that the Irish company would be covered by the nation’s Hoguet Law because there was not proper notification of the intention to apply French law to the Irish company.

Patine

Deity

- Joined

- Feb 14, 2011

- Messages

- 12,041

And the main effect of CETA - the general offensiveness of Ms. Freeland notwithstanding - is probably that we're paying them less.

Ah, yes. Yet another scapegoat to blame for all the troubles you see in the world - who doesn't have the power and influence to even remotely pull it off alone. When will you call to task, in a serious way, those you CLAIM to so vehemently oppose - the reactionary, nationalistic far-right groups - and whom you have treated, strangely, with kid gloves and prefer to blame "Anglosphere liberals" for EVERYTHING they do and get away with, instead? Sounds VERY disingenuous to me. And, when will you, in a rhetorical sense toward the blame and responsibility thing, finally "look in the mirror?"

innonimatu

the resident Cassandra

- Joined

- Dec 4, 2006

- Messages

- 15,377

Speaking of the Anglos - and Germany - I highly recommend reading this piece on the history of how the EU became what it is. I do not agree with everything the author writes (namely, the hope of the left in several countries managing to take over the monster...), but for the sake of good discussion the whole text merits attention. His descriptions of the roles played by people in several of the member countries is one of the best short descriptions I have found.

Quoting just a few paragraphs:

So that it does not get hidden unless expanded, it is worth quoting this part separately:

The author however is somewhat deluded in thinking that there is a way out in changing the EU institution for the better. His description of the situation is Portugal is simply wrong:

Budget cuts and privatizations were not really rolled back, they were just suspended, in the sense that more of this ceased being done. That was, in the PM's appreciation (and probably correct) the limit of what the EU would "tolerate". The growth was indeed part luck, tourism picking up. Investment in critical areas remains far below the values prior to the crisis and public services face ongoing (slower) degradation, both in personnel and in material, due to budget restrictions. Whenever the international credit cycle ends the results of this will be devastating.

Centeno, though he is a decent person in my opinion (the only one in the family...), continues to play the role of the austeritarian apostle. Proof of this is that the stranglehold on Greece was not relieved.

So while it is true that there is a battle to be fought inside each country if neoliberalism is to be beaten, the EU remains thoroughly neoliberal and ready as a shield to protect any of the so-called "reforms" that implemented liberalism inside each country. It keeps indeed demanding more of thoe. And under these conditions the fight against it is much, much harder, perhaps impossible. Imho the EU has to break before an Europe free from this disaster can be remade.

Quoting just a few paragraphs:

One initial European response to the 2008 shock was to blame Anglo-American free market ideology for infecting a traditionally social-democratic continent. This was always a weak alibi at a purely material level: as Adam Tooze has recounted, Europe’s overgrown banking sector played a key role in causing the global finance crisis. The impression of European innocence is equally untenable in the realm of ideology; scholars like Quinn Slobodian have recovered the Central European origins of many key neoliberal thinkers over the last decade. Some historians of neoliberalism have thought in terms of a “road from Mont Pèlerin,” the Swiss town where the most influential network of laissez-faire economists and lawyers originated in 1947. Analytically, this argument presupposes a pattern of influence that runs outward from a single center: market-friendly ideas may have been adapted to local contexts, but they essentially derived from a single concentrated template.

But there is a difference between the concentrated point of origin of neoliberal ideas and the diffuse successes of neoliberalism as an electoral program and policy agenda. After World War II, West Germany was an outlier in that it never adhered to the kind of strongly interventionist economic policy that characterized postwar growth elsewhere. For this reason, the country plays a major role in most narratives of how the EU became neoliberal, with the reunification of Germany as a key turning point. Left-wing critics of the EU often reason backwards: if the Eurozone and EU budget treaties have disproportionately benefited Germany, then those institutions must have been German ideas to begin with. Following that logic, the entire common currency and the structure of budget discipline get cast as instruments of German power over the continent. The implication is that reclaiming national sovereignty by leaving the euro or the Union will allow member states such as France, Italy, and Spain to return to their natural inclination for big-spending statist welfare regimes.

[...]

The political trajectories of the five non-German EEC countries in the 1980s and early 1990s show a different picture. Elites in these countries pursued their own agendas, for their own reasons. François Mitterrand, elected as President of France in 1981 on hopes of a socialist transformation, pursued left-wing economics for less than two years before capitulating in his infamous “turn to rigor” in March 1983, after which he transformed into the most avid privatizer in French history. Mitterrand’s liberalization agenda was run by a group of influential Socialist Party members, who eventually led a global campaign to abolish capital controls: Jacques Delors, first Mitterrand’s finance minister and later president of the European Commission; Michel Camdessus, Bank of France governor and IMF chairman from 1987 to 2000; and Henri Chavranski, who ran capital movements at the OECD. Far from victims of German hegemony, these policymakers were self-consciously trying to transform their political economies to adjust to the new world created by the end of fixed exchange rates and the onset of worldwide financialization. They wanted leaner and meaner states that would be able to preserve social provisions in a much tougher international environment.

A similar national makeover with an eye to global competition occurred in the Netherlands, where the Christian democrat Ruud Lubbers (1982-1994) forced his country’s labor unions into a new wage-suppressing compact. This allowed the Dutch to shadow the export-driven growth trajectory and hard money policies of Germany, but it was in no way done at the behest of the Germans. In the south, Italy temporarily overtook Britain in GDP in 1987 to become the world’s fourth-largest economy—the sorpasso or “overtaking”—but the unequal gains of this growth were further compounded by an enormous expansion in public debt. Following the implosion of the entire postwar Italian political system in 1992, Silvio Berlusconi and his successors began to pursue privatization and deregulation in earnest. A similar slash-and-burn procedure in Belgium under prime minister Wilfried Martens (1981-1992), who lowered taxes and nearly doubled the government debt, set the stage for his successors to cut back entitlements.

Yet it may be the Duchy of Luxembourg, the smallest of the founding six, that best illustrates the conversion of Europe’s national elites to neoliberalism. A hilly territory with a population under 400,000 people, Luxembourg’s steel-making economy supported a Christian Democratic welfare state for much of the postwar period. The duchy’s interstitial position and its middle-of-the-road politics also made it a reliable source of European Commission presidents: prime minister Pierre Werner proposed a common currency as a strategy to gain independence from American hegemony as early as 1970. But as free market ideas swept European capitals in the 1980s, the meaning of further economic and financial integration changed. Under prime minister Jacques Santer (1984–1995), the duchy reinvented itself as a global corporate tax haven and a sanctuary for money market funds from around the world. Santer’s agenda was executed by his right-hand man, the affable and self-effacing lawyer Jean-Claude Juncker.

So that it does not get hidden unless expanded, it is worth quoting this part separately:

Europe’s neoliberal transformation reached its apogee in the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, the preface of which defined the European Union as a “social market economy”—the original ordoliberal slogan developed in 1940s West Germany, in which the state’s economic role was that of a referee, not a player. The measure of this victory of market conformity was how many social democratic governments implemented these reforms — Gerhard Schröder’s SPD in Germany, Lionel Jospin’s PS in France, Romano Prodi’s L’Ulivo coalitions in Italy, Blair and Brown’s New Labour in Britain— and how avidly they did so.

The author however is somewhat deluded in thinking that there is a way out in changing the EU institution for the better. His description of the situation is Portugal is simply wrong:

Portugal has been the only Eurozone and EU member state which has been able to combine left-wing economic and social policies with material recovery while remaining committed to European institutions. The Portuguese progressive experiment under Lisbon’s former mayor, the Socialist prime minister António Costa, illustrates one possible path for the European left: capturing power in national elections and rolling back budget cuts and privatizations, thereby boosting growth and reducing debt.

Budget cuts and privatizations were not really rolled back, they were just suspended, in the sense that more of this ceased being done. That was, in the PM's appreciation (and probably correct) the limit of what the EU would "tolerate". The growth was indeed part luck, tourism picking up. Investment in critical areas remains far below the values prior to the crisis and public services face ongoing (slower) degradation, both in personnel and in material, due to budget restrictions. Whenever the international credit cycle ends the results of this will be devastating.

Centeno, though he is a decent person in my opinion (the only one in the family...), continues to play the role of the austeritarian apostle. Proof of this is that the stranglehold on Greece was not relieved.

So while it is true that there is a battle to be fought inside each country if neoliberalism is to be beaten, the EU remains thoroughly neoliberal and ready as a shield to protect any of the so-called "reforms" that implemented liberalism inside each country. It keeps indeed demanding more of thoe. And under these conditions the fight against it is much, much harder, perhaps impossible. Imho the EU has to break before an Europe free from this disaster can be remade.

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 82

- Views

- 2K