I must admit it seems to me there's a pretty clear difference between greeting someone and reciting an oath, even considered purely as a social ritual. It's a public statement of belief and commitment, not merely a gesture that has no overt meaning.

I disagree; rituals matter and they never have "no overt meaning." Human communities are rife with little rituals that exist primarily for building connections between the people in a community as well as bonding people to the community at large. The relationship, the bonds, that I have with a friend in my social is different from the relationship that a child has with the government that protects her rights, sustains her security, and provides her education free of charge. So the cementing rituals will be, obviously, different rituals.

Our relationships are less formal than our social contracts with our various governments, and so they'll have less formality in them. The rituals you go through with your friends are personalized, customized to how yall get along. But that doesn't make them unimportant. Rituals build connections and connections sustain friendships past the natural frictions that occur whenever your interest or values might come into conflict.

Personal social rituals exist to help only my personal relationships. The relationship of the citizen with the state is the very foundation of sustaining liveable communities. Both rituals have overt meanings, even if the Pledge is more important. Less is riding on one interpersonal relationship, but that's not to say that it doesn't matter. Having a resilient circle of friends can make a huge difference in someone's life--although it would be on a different scale than one's relationship with a government.

Now, a lot of people complain that the Pledge to the American flag is silly, or is indoctrination, or forces a state ideology on the child. Some say it's hypocritical to have a country based on personal liberty then go ahead and mandate that its kids all recite a statement of beliefs in unison. But my larger point was that we have a myriad of rituals in our lives and every one of them is about establishing a place and an identity within the context of a larger social unit, be it a church, a country, or a circle of friends.

It strikes me as reasonable and just that the government ask that a child pledge allegiance to our form of government, of which the flag is only a token. This makes sense because this child will be expected as an adult in the future to sustain that form of government so that future generations of Americans can also enjoy the rights and benefits that she as a child is now enjoying. We all have a covenant with future generations to pass along to them a workable, liveable world. Establishing among today's children a sense of being part of that covenant is necessary for sustaining that covenant with the future by sustaining the government that exists to carry out that covenant. This is at the heart of how societies maintain their values over time.

Is this particular flag pledge ritual indispensable? No, it's just a ritual. Maybe someone could come up with a better one. But the very existence and unchanging nature of rituals is part of their strength. If you monkey around with them, they become less important. Rituals have a concrete value: they reinforce social bonds; they communicate social norms; they remind us that there's a larger purpose going on with each day's smaller actions. The absence of ritual exposes those important social bonds to neglect, if they're taken for granted. So ritual is needed; ritual matters.

But I must ask, purely for information: as a teacher leading this particular ritual, do you have a choice? Could you not participate if you didn't want to?

As a purely philosophical statement, the Pledge to the American flag is pretty bland. You salute the flag and commit to a republican form of government. That's all there is to it. But even at that, it's still permissible to opt out. Lots of kids do. It doesn't bother me, because they've at least thought about what they're doing--and a questioning public serves the purposes of a republic anyway.

As a functionary of a social organ, it's not really my business to choose, for myself whether I order kids to stand for the pledge. Most of them don't say it anyway. The repetition, the standing, the respect for the icon of the government--that's important too. It's 30 seconds of deference in an 8 hour school day; not a big price. But repeated day after day, it is a useful reminder of what it all comes down to.

I reckon if it really bothered me to salute the flag, I could opt out. No one's around to enforce it. But as a social studies teacher, I have a special obligation not to infuse my political biases into the teaching of history. I surrender that to the process because I want to live in a country where kids get educated by the facts first and form their own opinions later. By the same token I don't choose to question how much I buy into the need for this particular ritual. My employer asks me to do it and the request makes sense. I'm a public servant; so seeing no injustice done, I comply.

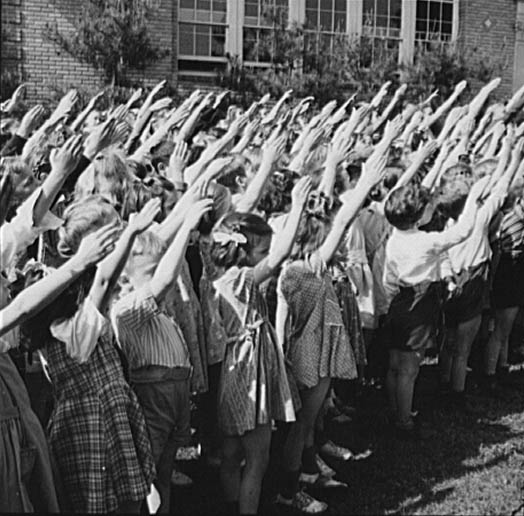

to see conservatives extolling the virtues of reciting "patriotic" mantras from a national socialist.

to see conservatives extolling the virtues of reciting "patriotic" mantras from a national socialist.