‘Fantastic’ particle could be most energetic neutrino ever detected

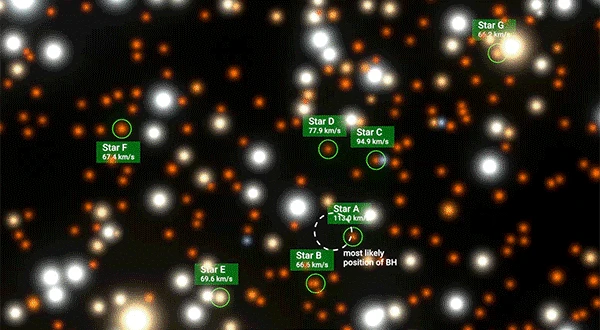

An observatory still under construction at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea has spotted what could be the most energetic neutrino ever detected. Such ultra-high-energy neutrinos — tiny subatomic particles that travel at nearly the speed of light — have been known to exist for only a decade or so, and are thought to be messengers from some of the Universe’s most cataclysmic events, such as growth spurts of supermassive black holes in distant galaxies.

Neutrino physicist João Coelho stunned researchers at the Neutrino 2024 conference in Milan, Italy, on 18 June, when he revealed the discovery only at the very end of his talk.

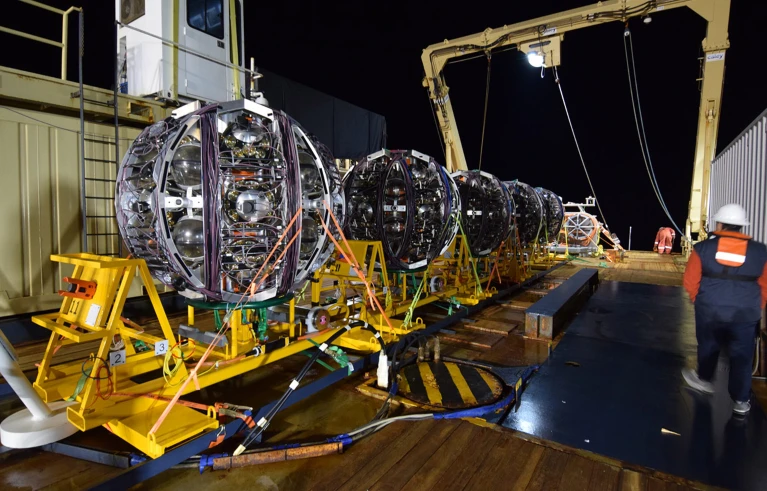

The neutrino detection was “a fantastic event”, says Francis Halzen, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He added that the observation highlights the potential of the Astroparticle Research with Cosmics in the Abyss (ARCA) observatory — a forest of detectors on ‘strings’ attached to the 3,500-metre-deep sea floor southeast of the Italian island of Sicily.

The neutrino “really stands out, very far away from anything else”, said Coelho, who is at the AstroParticle and Cosmology Laboratory in Paris. He did not disclose the precise direction from which the particle had come, nor when the observation occurred: doing so could have tipped off competitors about the possible origin of the neutrino, researchers at the conference told Nature. Coelho instead promised that these details would be revealed in a paper further down the line. “It would be really interesting to see where in the sky the neutrino originated,” says Nepomuk Otte, a physicist at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

The majority of the light that ARCA detects is the result of highly energetic cosmic-ray particles, which produce showers of electrically charged subatomic particles when they hit Earth’s atmosphere. These particle showers can travel in water for kilometres and leave behind faint flashes of light, which ARCA is designed to spot.

The observatory can also detect light from other kinds of particle, including neutrinos. It does not ‘see’ neutrinos directly. Instead, when a neutrino hits a molecule — of air, water or underlying rock — it can create a highly energetic charged particle called a muon, which produces a shower of other charged particles as it moves through the detector. Neutrinos can travel through Earth, so the particle showers that they produce can come from any direction, whereas those resulting from cosmic rays tend to come from the atmosphere. So, when ARCA detects a shower from above, it can be difficult to determine the source, but showers that are horizontal or upwards-moving are most likely to be neutrinos, says Elisa Resconi, a neutrino physicist at the Technical University of Munich in Germany.

But for the highest-energy neutrinos — those carrying half a petaelectronvolt (0.5x1015 eV) or more — the Earth acts as a barrier, says Resconi. That leaves a strip of sky around the horizon where the Earth-skimming particles can be detected and easily distinguished from cosmic rays. “We have this narrow region in which we can see very clean signatures of these neutrinos,” says Resconi, who is part of the collaboration that discovered ultra-high-energy neutrinos around a decade ago; that group used the much larger IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a detector similar to ARCA that is embedded in Antarctic ice.

Five ARCA detectors on board a ship, ready for deployment.