You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

December World - game thread

- Thread starter Ahigin

- Start date

tobiisagoodboy

Prince

Pharissär, the perfect to keep warm and fool your church. Cook liquor and then mix it with hot coffee and cover it with whipped cream, so nobody can smell the booze.

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

The Sikh Man

Two parts gin, one part absinthe.

Favourite drink of foreigners and impious men alike.

Although tharra was originally used instead of gin, the unavailability of licensed and regulated tharra led to its substitution by wary foreigners. The original can still be found in sleazy joints.

Two parts gin, one part absinthe.

Favourite drink of foreigners and impious men alike.

Although tharra was originally used instead of gin, the unavailability of licensed and regulated tharra led to its substitution by wary foreigners. The original can still be found in sleazy joints.

Last edited:

Crezth

i knew you were a real man of the left

The Jo'burg Glider

2 parts Witblits (a type of brandy fermented from grapes)

1 part cointreau or triple-sec

1 part lemon juice

Add a slice of orange and serve without ice.

2 parts Witblits (a type of brandy fermented from grapes)

1 part cointreau or triple-sec

1 part lemon juice

Add a slice of orange and serve without ice.

Traveller76

Prince

Margarita

7 parts Tequila

4 part Cointreau

3 parts Lime Juice

Pour all ingredients into a shaker with ice. Shake well and strain into cocktail glass rimmed with salt.

7 parts Tequila

4 part Cointreau

3 parts Lime Juice

Pour all ingredients into a shaker with ice. Shake well and strain into cocktail glass rimmed with salt.

Important organizational announcement

It's become known to me that some resourceful players have found a way to point out at culprits of secret spy actions by finding patterns in their losses, even if I mask the name of the culprit. At first, I didn't think much about the impact that action would have on the game, but it seems like a lot of players are now drawn to withholding from espionage all together or are ready to do that only if I mask their losses as well. I can do that, but it'd make the game less fun, because now you'd never know how effective (or not effective) your police was against foreign agents, depriving you of useful information.

Therefore, I'll start with a soft approach: please don't use this and any other metagame methods of investigating espionage and sabotage, and if you learn some information via in-game means, please don't share it with other players via metagame channels. I respect your ingenuity and curiosity, but part of the fun of this game is playing geopolitics, which, in turn, requires some intrigue.

If this soft approach fails (and trust me, I'll know if it does), I'll have to mask all espionage/sabotage losses from now on. Not much fun for me, not much fun for you. But it's better than people being afraid of doing espionage.

Thank you.

It's become known to me that some resourceful players have found a way to point out at culprits of secret spy actions by finding patterns in their losses, even if I mask the name of the culprit. At first, I didn't think much about the impact that action would have on the game, but it seems like a lot of players are now drawn to withholding from espionage all together or are ready to do that only if I mask their losses as well. I can do that, but it'd make the game less fun, because now you'd never know how effective (or not effective) your police was against foreign agents, depriving you of useful information.

Therefore, I'll start with a soft approach: please don't use this and any other metagame methods of investigating espionage and sabotage, and if you learn some information via in-game means, please don't share it with other players via metagame channels. I respect your ingenuity and curiosity, but part of the fun of this game is playing geopolitics, which, in turn, requires some intrigue.

If this soft approach fails (and trust me, I'll know if it does), I'll have to mask all espionage/sabotage losses from now on. Not much fun for me, not much fun for you. But it's better than people being afraid of doing espionage.

Thank you.

Just to brief rule-related reminders to everyone submitting their orders.

1. Newly researched technologies can be adopted by other nations only two turns after the research is completed. They're too fresh and unusual for the world to accept them quickly. (This has impacted some sets of orders last turn, and I see it again this turn, so just want to set expectations straight.)

2. Until a quest is completed all the way (or fails all the way, whichever applies), it won't result in any non-RP results. Finish your quests if you want to receive bonuses they give.

1. Newly researched technologies can be adopted by other nations only two turns after the research is completed. They're too fresh and unusual for the world to accept them quickly. (This has impacted some sets of orders last turn, and I see it again this turn, so just want to set expectations straight.)

2. Until a quest is completed all the way (or fails all the way, whichever applies), it won't result in any non-RP results. Finish your quests if you want to receive bonuses they give.

Sniiperman456

Warlord

- Joined

- Nov 5, 2016

- Messages

- 253

Instead of worrying about wine recipes, I just go to a wine shop and buy a normal wine bottle.

Immaculate

unerring

- Joined

- Jan 22, 2003

- Messages

- 7,623

wine box.

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

Goon is the most repugnant form of wine. Especially if you let it become vinegar. Ew.

Crezth

i knew you were a real man of the left

Instead of worrying about wine recipes, I just go to a wine shop and buy a normal wine bottle.

"Hello I'll have one bottle of normal wine, please."

thomas.berubeg

Wandering the World

"Hello I'll have one bottle of normal wine, please."

thomas.berubeg

Wandering the World

Also, for what it's worth, Hungary has an incredibly rich alcoholic tradition.Instead of worrying about wine recipes, I just go to a wine shop and buy a normal wine bottle.

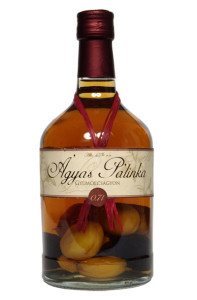

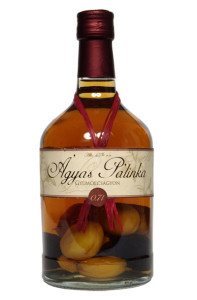

There's Palinka:

Palinka is a (Usually Clear) brandy like liquor, made from any number of local Hungarian fruit (in fact, IIRC, it can't NOT be fruit,) most commonly apricot, plums, cherries, apples, or pears. I've seen it sometimes with some of the fruit infusing in it, enhancing that particular flavor. It's drunk at room temperature, because too cold, and you don't get the fruit flavors. It's pretty strong, and, legally, producible by literally anyone.

There's Unicum

It's an herbal Liquor, similar conceptually to, say, Jaegar, or chartreuse. It's only produced by one company, now, Zwack, who have a secret recipe that they claim contains more than 40 distinct herbs. I tend to find it pretty foul, but it IS the national drink of Hungary.

There are Hungarian Vodkas, too, but they're not very common, and, from what I've been told, if you ask for Vodka, oftentimes you're going to get a Palinka.

And, yes, Hungary does have wines, two of which of famous outside of Hungary itself. Tokaji is a wine made with grapes with "Noble Rot," which is a fungus affecting wine grapes in moist regions. If dried at the right time, it makes for a pretty sweet wine. Though the technique of using Noble Rot is in use in other places, it comes from Hungary and is a distinctive Hungarian thing. Tokaji, the wine itself, is made in the Tokaj region, and, for manufacturing purposes, like champagne, can only be called so if produced in the region. (There are actually a pretty large variety of Tokaji, though I myself associate those kinds of wine with a sweet white bubbly. I know there are some reds, some dry whites, some bubblies.) Historically, production of wine in the Tokaj region dates back at least to Arpad himself, though it's likely the region was a winemaking region for a lot longer than that.)

There's also "Bull's blood," or Egri Bikaver, which supposedly dates back to the 16th century, to the Seige of Eger, when the soldiers were wined and dined by the lord to keep up their vigor and Morale. The Turkish soldiers blamed the resolve of the Defenders on a secret ingredient in the wine, Bull's blood. What IS known is that the red wine grapes were introduced to Hungary by the Turks, replacing/complementing the local white grapes. Bulls' Blood itself is generally a blend of grapes, and, according to wikipedia (I didn't know this) must have at least three of these grapes: Bíbor kadarka, Blauburger, Cabernet franc, Cabernet sauvignon, Kadarka, Kékfrankos, Kékoportó, Menoire, Merlot, Pinot noir, Syrah, Turán, Zweigelt. The Wine itself is aged for at least three years in oak barrels. It tastes pretty strong, having a distinctish spicy pallet - and is delicious with a lot of Hungarian type stews, especially in winter.

I'm SURE there's also quite a bit of hungarian beers, but none really stick out to me off the top of my head.

...

Now I wish I was playing Hungary. It'd be the culinary capital of the world! I can go on for a hell of a long time about hungarian cuisine. IF anyone is interested, check out this book: I've used it so much.

On that monumental (and highly educational) post, I'll call the end of the alcohol discussion and meme/joke exchange regarding it in this thread. You are, however, more than welcome to continue it in Discord, because, as Shadowbound said, drinking is important. (The only exception I'm willing to make is if you post some good, thought-through cocktail recipes about your in-game nation, as a sort of background/setting info. And when I say "good," I mean I expect them to be good enough for you to be willing to drink them if we meet in real life (the drink's on me)).

World Tension update:

As two wars have been declared in the very heart of Europe, and multiple more wars seem to be looming on the horizon, the world tensions have risen. Nations mobilize their resources, scientists are preparing for a giant technological leap, and people across the globe wake up with the same sense of determination, worry, or anxiety that keeps the world going.

At this level of World Tension, all updates will cover the span of half a year, from January to late June (Q1-Q2). All of your resource production, in-game actions, research, etc. will stay the same, reflecting how the world has mobilized for this brave, new age.

World Tension update:

As two wars have been declared in the very heart of Europe, and multiple more wars seem to be looming on the horizon, the world tensions have risen. Nations mobilize their resources, scientists are preparing for a giant technological leap, and people across the globe wake up with the same sense of determination, worry, or anxiety that keeps the world going.

At this level of World Tension, all updates will cover the span of half a year, from January to late June (Q1-Q2). All of your resource production, in-game actions, research, etc. will stay the same, reflecting how the world has mobilized for this brave, new age.

Sniiperman456

Warlord

- Joined

- Nov 5, 2016

- Messages

- 253

I would prefer if you didn't roleplay stuff about my country without my permission?Also, for what it's worth, Hungary has an incredibly rich alcoholic tradition.

There's Palinka:

Palinka is a (Usually Clear) brandy like liquor, made from any number of local Hungarian fruit (in fact, IIRC, it can't NOT be fruit,) most commonly apricot, plums, cherries, apples, or pears. I've seen it sometimes with some of the fruit infusing in it, enhancing that particular flavor. It's drunk at room temperature, because too cold, and you don't get the fruit flavors. It's pretty strong, and, legally, producible by literally anyone.

There's Unicum

It's an herbal Liquor, similar conceptually to, say, Jaegar, or chartreuse. It's only produced by one company, now, Zwack, who have a secret recipe that they claim contains more than 40 distinct herbs. I tend to find it pretty foul, but it IS the national drink of Hungary.

There are Hungarian Vodkas, too, but they're not very common, and, from what I've been told, if you ask for Vodka, oftentimes you're going to get a Palinka.

And, yes, Hungary does have wines, two of which of famous outside of Hungary itself. Tokaji is a wine made with grapes with "Noble Rot," which is a fungus affecting wine grapes in moist regions. If dried at the right time, it makes for a pretty sweet wine. Though the technique of using Noble Rot is in use in other places, it comes from Hungary and is a distinctive Hungarian thing. Tokaji, the wine itself, is made in the Tokaj region, and, for manufacturing purposes, like champagne, can only be called so if produced in the region. (There are actually a pretty large variety of Tokaji, though I myself associate those kinds of wine with a sweet white bubbly. I know there are some reds, some dry whites, some bubblies.) Historically, production of wine in the Tokaj region dates back at least to Arpad himself, though it's likely the region was a winemaking region for a lot longer than that.)

There's also "Bull's blood," or Egri Bikaver, which supposedly dates back to the 16th century, to the Seige of Eger, when the soldiers were wined and dined by the lord to keep up their vigor and Morale. The Turkish soldiers blamed the resolve of the Defenders on a secret ingredient in the wine, Bull's blood. What IS known is that the red wine grapes were introduced to Hungary by the Turks, replacing/complementing the local white grapes. Bulls' Blood itself is generally a blend of grapes, and, according to wikipedia (I didn't know this) must have at least three of these grapes: Bíbor kadarka, Blauburger, Cabernet franc, Cabernet sauvignon, Kadarka, Kékfrankos, Kékoportó, Menoire, Merlot, Pinot noir, Syrah, Turán, Zweigelt. The Wine itself is aged for at least three years in oak barrels. It tastes pretty strong, having a distinctish spicy pallet - and is delicious with a lot of Hungarian type stews, especially in winter.

I'm SURE there's also quite a bit of hungarian beers, but none really stick out to me off the top of my head.

...

Now I wish I was playing Hungary. It'd be the culinary capital of the world! I can go on for a hell of a long time about hungarian cuisine. IF anyone is interested, check out this book: I've used it so much.

This is not roleplay, it's what Hungarians actually drink. But you're welcome to add to this if you wish.

I do agree that players shouldn't probably make up leaders, events, etc. for other nations. But whether or not real Hungarian alcohol is being consumed by in-game Hungarians? I'd say Thomas didn't break any in-game etiquette. There's snow in Russia, regardless if Shadowbound agrees with it or not.

I do agree that players shouldn't probably make up leaders, events, etc. for other nations. But whether or not real Hungarian alcohol is being consumed by in-game Hungarians? I'd say Thomas didn't break any in-game etiquette. There's snow in Russia, regardless if Shadowbound agrees with it or not.

The Profession

Question. What is your name?

Answer. Baoluo Li.

Question. Who gave you this name?

Answer. My Godfathers in my Baptism, where I was made one with Christ and Hong, a child of God, and an inheritor of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Question: What was your previous name?

Answer: Murhaci Gioro.

Question: That was a Manchu name, correct?

Baoluo hestitates. A bead of sweat drips off his head. The admission had come after six months of imprisonment.

Answer: Yes, I am ashamed to say. I have discarded it.

Question: Good. Very good. Now what did your Godfathers ask from you?

Answer: That I vow three things: First that I renounce the devil and all his works. Secondly, that I profess all the articles of the Christian faith. And third...

Baoluo pauses, his eyes range the room seeming to search for the right words. He focuses on the questioner, Comrade Questioner Pan, who nods with encouragement...

...that I should keep God's commandments and keep to them all the days of my life.

Pan smiles. His lips thin on a leathery peasant face. The hair long since gone to silver. Long hairs protrude from a nose that's been broken flat. His eyebrows a single chaotic line. His body lean, hard. A powerful chest strains his tunic. His accent had taken months for Baoluo's northern ears to get used to.

Question: Very good, Li. Do you think that that you can as you have promised?

Answer: Yes and with God's help I will. I thank God Almighty that he has called me to salvation, through our Saviours Christ and Hong. I pray that God will give me the strength that I may continue that way for the rest of my life.

Question: Now repeat the articles of the faith.

Answer: I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.

And in Jesus Christ, His elder Son, our Lord; Who was conceived by the Holy Spirit; Born of the Virgin Mary; Suffered under Pontius Pilate; Was crucified, dead and buried; He descended into Hell; The third day He rose again from the dead; He ascended into heaven; And sitteth on the right hand of God the Father Almighty; From thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

Another pause from Baoluo. He draws in a deep breath. It had taken him eight months of imprisonment to say these words. The first few times as a whisper. But he had spoken them earnestly that morning during his baptism and he would do so again.

And in Hong Xiuquan, His younger Son, our Lord; Who was concieved by the Holy Spirit; Born of the Virgin Wang; Suffered under demonic torment; He defeated the evil one; descended on Najing; in the fifteenth year He triumphed; thence he ascended into heaven; And sitteth on the left hand of God the Father Almighty; From thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Spirit; The Holy Christian Church, the Communion of Saints; The Forgiveness of sins; The Resurrection of the body; And the life everlasting. Amen.

Pan smiled once more. The lines around his eyes gave him a grandfatherly look. In the first few months of his captivity, Baoluo's had dimissed Pan as a dumb peasant. Pan was a peasant, that much was true, but he was not stupid. Pan was sharp, uncommonly so. Pan had been the one to force an admission of Baoluo's now discarded Manchu name. The other Questioners had accepted Bauluo's lie that he was just another Han. He still wasn't quite sure how old Pan had figured out he was a Manchu but the old fox had.

Question. You said that your Godfathers ask that you should keep God's Commandments. Tell me how many there are?

Answer. Ten.

Question. A quick test. We will depart from the script for just a while. Do not be afraid. Do you happen to know the words of Proverbs 14:5? It's in the short course.

Bauluo draws in a confused breathe. He think and then recites the words from memory.

Answer: An honest witness does not deceive, but a false witness pours out lies.

Question: What is ninth commandment?

Bauluo takes another breath.. and hestitates. Why these two questions? Why depart from the script? Bauluo recites again from memory.

Answer: Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.

Question: What do you these tell you?

Answer: My duty to my neighbour -- the Golden Rule.

Question: Succinct. I like that. Most stumble on this part.

Question. What is your duty towards your neighbour?

Bauluo pauses. Draws a breath. Ponders the question. His mind races. Could they know? But how? Nobody could know? He barely believed it himself now.

Answer: My duty is to love my neighbour as I love myself...

Pan smiles and cuts Bauluo off with a gesture.

Question: Comrade Bauluo have you treated all your brothers with love?

Answer: I don't understand the question.

Question: You are not Murhaci Gioro. You are Surgaci his elder brother correct? The second son. Nurhaci is the eldest.

Surgaci goes white. His heart skips a beat. Then another. Then more still. He wonders if he's been poisoned. Pan smiles his eyes glearming with peasant cunning.

Answer: Yes. I suppose I am.

Question: That's very good Colonel Surgaci. You were a member of the Manchu Warlord Intelligence Clique, correct?

Answer: Yes.

The admission seems to drain Surgaci. He slumps into his chair defeated. The hope that had bouyed him for the eleven months he had been in captivity was gone. His attempt to be a Han had failed and now his attempt to pass as his dead younger brother had failed. Pan, the old fox, had seen straight through him. But how? He didn't know. He had been so careful.

Question: You are good Surgaci. The others almost let you go the first time. You played the part of a Han perfectly. You underestimated me. That's not to be ashamed of. I'm good at what I do. As are you, Comrade. How do you think we figured out you were a Manchu?

Surgaci decides to humour the old man. His mind casts around looking for some mistake, some slip in his persona. He finds none.

Answer: Truthfully, I have no idea. I've pondered the question for the past five months. I'm still not closer to the answer.

Question: Here's the answer. When you first entered the camp, you looked at the Manchu instructions first. It was a glance but it was noted. You also had trouble joining in the camp songs. You didn't know the words. You mouthed them the first few times. Do you remember when the women walked past?

Answer: Yes, of course, that was the first time I had seen women for three months.

Pan lets out a burst of laughter and resumes smiling.

Question: You didn't give the lotus feet a second glance. It's a dead giveaway. It's been our most effective way of smoking out your kind. I came up with it. I'm quite proud of it to be frank. Now how do you think we figured out you were Surgaci and not, as you claimed, Murhaci?

Surgaci sits quietly with his eyes closed lost in thought. A few minutes go by.

Answer: I didn't make any obvious mistakes. I also don't know any of the men here, and besides I look very much like my brother. We're not twins but we might as well be. Besides, I'm only 18 months older than him. I honestly have no idea Pan.

Question: How did you find our your brother was dead?

Answer: My mother recieved a letter. It was a few days after the war had ended. The letter was late it was dated a few months ago. The postal system was in chaos, we had known for a while he must be dead, but it was still a shock.

Question: Your brother is alive. He was taken prisoner. He confessed who he was just before you tried to impersonate him. I will freely admit our records are in a shambles so it took longer than it should. The Honghuzi have kept us busy. The others argued you should be released as a low risk prisoner. Your brother was just a reserve artillerist. I didn't trust you so I held you back. Does that answer your question?

Answer: I suppose it does. It was luck then?

Question: Hong smiled on this old soldier. Now comrade what should we do with you?

Answer: As we've now established I'm an officer. I would only ask that you execute me as one. I won't need a blindfold. I just ask that the men shoot straight. Would you me the honour of leading the firing squad Pan?

Question: My dear boy, I would be honoured. But that would be a waste. I suppose what I'm offering is a job. Would you be interested?

The former colonel, now prisoner Surgaci freezes, his face goes red and contorts with rage.

Answer: That's a cruel joke to play! I wouldn't have figured you for the sort to play with a man like that!

A dry laugh leaves Pans lips. Eyes which normally shine with mirth turn flat. A slight smirk twists the corner of his mouth.

Question: I'm dead serious. You've impressed me. Very few have lasted half as long as you. This is really your only other chance. The others want you dead. I think that's a waste. I've cleared it with the boss. She's quite keen to meet you. Are you interested?

Answer: Yes, I am. But why are you sparing me?

Question: Just remember your Bible training comrade. "If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins purify us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:9). That applies to you, as much as it applies to me. You believe now. I know that. You know that. Why not take the opportunity to do good in the world?

Surgaci who has held himself so well begins to cry. Tears roll down his face. He cannot remember when he last wept so much. But these are not tears of sadness. These are tears of joy for the weight that had been sitting on his soul all his life, the weight that he had never noticed but which had suffused his whole being, had been lifted and with it came the realisation that his soul was now free. In the world just past the door of his cell, new snow had just begun to fall covering the cold Manchurian plain in a blanket of purest, perfect white.

Question. What is your name?

Answer. Baoluo Li.

Question. Who gave you this name?

Answer. My Godfathers in my Baptism, where I was made one with Christ and Hong, a child of God, and an inheritor of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Question: What was your previous name?

Answer: Murhaci Gioro.

Question: That was a Manchu name, correct?

Baoluo hestitates. A bead of sweat drips off his head. The admission had come after six months of imprisonment.

Answer: Yes, I am ashamed to say. I have discarded it.

Question: Good. Very good. Now what did your Godfathers ask from you?

Answer: That I vow three things: First that I renounce the devil and all his works. Secondly, that I profess all the articles of the Christian faith. And third...

Baoluo pauses, his eyes range the room seeming to search for the right words. He focuses on the questioner, Comrade Questioner Pan, who nods with encouragement...

...that I should keep God's commandments and keep to them all the days of my life.

Pan smiles. His lips thin on a leathery peasant face. The hair long since gone to silver. Long hairs protrude from a nose that's been broken flat. His eyebrows a single chaotic line. His body lean, hard. A powerful chest strains his tunic. His accent had taken months for Baoluo's northern ears to get used to.

Question: Very good, Li. Do you think that that you can as you have promised?

Answer: Yes and with God's help I will. I thank God Almighty that he has called me to salvation, through our Saviours Christ and Hong. I pray that God will give me the strength that I may continue that way for the rest of my life.

Question: Now repeat the articles of the faith.

Answer: I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.

And in Jesus Christ, His elder Son, our Lord; Who was conceived by the Holy Spirit; Born of the Virgin Mary; Suffered under Pontius Pilate; Was crucified, dead and buried; He descended into Hell; The third day He rose again from the dead; He ascended into heaven; And sitteth on the right hand of God the Father Almighty; From thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

Another pause from Baoluo. He draws in a deep breath. It had taken him eight months of imprisonment to say these words. The first few times as a whisper. But he had spoken them earnestly that morning during his baptism and he would do so again.

And in Hong Xiuquan, His younger Son, our Lord; Who was concieved by the Holy Spirit; Born of the Virgin Wang; Suffered under demonic torment; He defeated the evil one; descended on Najing; in the fifteenth year He triumphed; thence he ascended into heaven; And sitteth on the left hand of God the Father Almighty; From thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Spirit; The Holy Christian Church, the Communion of Saints; The Forgiveness of sins; The Resurrection of the body; And the life everlasting. Amen.

Pan smiled once more. The lines around his eyes gave him a grandfatherly look. In the first few months of his captivity, Baoluo's had dimissed Pan as a dumb peasant. Pan was a peasant, that much was true, but he was not stupid. Pan was sharp, uncommonly so. Pan had been the one to force an admission of Baoluo's now discarded Manchu name. The other Questioners had accepted Bauluo's lie that he was just another Han. He still wasn't quite sure how old Pan had figured out he was a Manchu but the old fox had.

Question. You said that your Godfathers ask that you should keep God's Commandments. Tell me how many there are?

Answer. Ten.

Question. A quick test. We will depart from the script for just a while. Do not be afraid. Do you happen to know the words of Proverbs 14:5? It's in the short course.

Bauluo draws in a confused breathe. He think and then recites the words from memory.

Answer: An honest witness does not deceive, but a false witness pours out lies.

Question: What is ninth commandment?

Bauluo takes another breath.. and hestitates. Why these two questions? Why depart from the script? Bauluo recites again from memory.

Answer: Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.

Question: What do you these tell you?

Answer: My duty to my neighbour -- the Golden Rule.

Question: Succinct. I like that. Most stumble on this part.

Question. What is your duty towards your neighbour?

Bauluo pauses. Draws a breath. Ponders the question. His mind races. Could they know? But how? Nobody could know? He barely believed it himself now.

Answer: My duty is to love my neighbour as I love myself...

Pan smiles and cuts Bauluo off with a gesture.

Question: Comrade Bauluo have you treated all your brothers with love?

Answer: I don't understand the question.

Question: You are not Murhaci Gioro. You are Surgaci his elder brother correct? The second son. Nurhaci is the eldest.

Surgaci goes white. His heart skips a beat. Then another. Then more still. He wonders if he's been poisoned. Pan smiles his eyes glearming with peasant cunning.

Answer: Yes. I suppose I am.

Question: That's very good Colonel Surgaci. You were a member of the Manchu Warlord Intelligence Clique, correct?

Answer: Yes.

The admission seems to drain Surgaci. He slumps into his chair defeated. The hope that had bouyed him for the eleven months he had been in captivity was gone. His attempt to be a Han had failed and now his attempt to pass as his dead younger brother had failed. Pan, the old fox, had seen straight through him. But how? He didn't know. He had been so careful.

Question: You are good Surgaci. The others almost let you go the first time. You played the part of a Han perfectly. You underestimated me. That's not to be ashamed of. I'm good at what I do. As are you, Comrade. How do you think we figured out you were a Manchu?

Surgaci decides to humour the old man. His mind casts around looking for some mistake, some slip in his persona. He finds none.

Answer: Truthfully, I have no idea. I've pondered the question for the past five months. I'm still not closer to the answer.

Question: Here's the answer. When you first entered the camp, you looked at the Manchu instructions first. It was a glance but it was noted. You also had trouble joining in the camp songs. You didn't know the words. You mouthed them the first few times. Do you remember when the women walked past?

Answer: Yes, of course, that was the first time I had seen women for three months.

Pan lets out a burst of laughter and resumes smiling.

Question: You didn't give the lotus feet a second glance. It's a dead giveaway. It's been our most effective way of smoking out your kind. I came up with it. I'm quite proud of it to be frank. Now how do you think we figured out you were Surgaci and not, as you claimed, Murhaci?

Surgaci sits quietly with his eyes closed lost in thought. A few minutes go by.

Answer: I didn't make any obvious mistakes. I also don't know any of the men here, and besides I look very much like my brother. We're not twins but we might as well be. Besides, I'm only 18 months older than him. I honestly have no idea Pan.

Question: How did you find our your brother was dead?

Answer: My mother recieved a letter. It was a few days after the war had ended. The letter was late it was dated a few months ago. The postal system was in chaos, we had known for a while he must be dead, but it was still a shock.

Question: Your brother is alive. He was taken prisoner. He confessed who he was just before you tried to impersonate him. I will freely admit our records are in a shambles so it took longer than it should. The Honghuzi have kept us busy. The others argued you should be released as a low risk prisoner. Your brother was just a reserve artillerist. I didn't trust you so I held you back. Does that answer your question?

Answer: I suppose it does. It was luck then?

Question: Hong smiled on this old soldier. Now comrade what should we do with you?

Answer: As we've now established I'm an officer. I would only ask that you execute me as one. I won't need a blindfold. I just ask that the men shoot straight. Would you me the honour of leading the firing squad Pan?

Question: My dear boy, I would be honoured. But that would be a waste. I suppose what I'm offering is a job. Would you be interested?

The former colonel, now prisoner Surgaci freezes, his face goes red and contorts with rage.

Answer: That's a cruel joke to play! I wouldn't have figured you for the sort to play with a man like that!

A dry laugh leaves Pans lips. Eyes which normally shine with mirth turn flat. A slight smirk twists the corner of his mouth.

Question: I'm dead serious. You've impressed me. Very few have lasted half as long as you. This is really your only other chance. The others want you dead. I think that's a waste. I've cleared it with the boss. She's quite keen to meet you. Are you interested?

Answer: Yes, I am. But why are you sparing me?

Question: Just remember your Bible training comrade. "If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins purify us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:9). That applies to you, as much as it applies to me. You believe now. I know that. You know that. Why not take the opportunity to do good in the world?

Surgaci who has held himself so well begins to cry. Tears roll down his face. He cannot remember when he last wept so much. But these are not tears of sadness. These are tears of joy for the weight that had been sitting on his soul all his life, the weight that he had never noticed but which had suffused his whole being, had been lifted and with it came the realisation that his soul was now free. In the world just past the door of his cell, new snow had just begun to fall covering the cold Manchurian plain in a blanket of purest, perfect white.

Last edited:

thomas.berubeg

Wandering the World

Confederate Culinaria:

The Deep South:

It is often said that the border with Maryland is the last place one can get good barbeque, though, undoubtedly there are some to the north who would disagree. The Confederate States boast three distinct styles of Barbeque, one of which is centered in North Carolina. Almost exclusively pork based, Atlantic Style Barbeque is known for vinegar based sauces, varying from almost exclusively vinegar in the east to a more robust tomato and spicy-sweet sauces towards the west. The cuts of meat usually barbequed are the Ribs, on the rack, and Butts (shoulder,) which makes a pulled pork, usually eaten in sandwiches. On special occasions, rural farmers may get together for a “pig-pickin’” where a whole pig is roasted in a pit.

Some regions of Virginia are well known for their Country Hams, which are protected by state law. These hams are salt-cured, and then smoked with cherry or apple wood, and finally left to age for anywhere between a few months and three years. Country hams are often cooked by boiling in several changes of water, and then pan frying lightly, just enough to brown the exteriors and warm up the meat. Some purists insist that the dry, salty, moldy crust must be eaten, but most people agree that the harder edges must be pared off before eaten. Often times, a red-eye gravy will be prepared with the drippings, as well as some Grits.

Hominy Grits, or just grits, may be the most quintessential culinary offering of the CSA, bar none, and nowhere is this more true than in the Atlantic and Deep south regions of the nation. Grits are, at it’s most fundamental, dried corn treated with Alkali and with the germ removed. These are ground, traditionally on a stone wheel, and prepared by boiling for in 5-6 times their volume in liquid, traditionally salted water or broth, but occasionally milk. They are typically seasoned with salt and pepper, and generous amounts of butter, but occasionally, grits are prepared with cheese, or with some sort of cooked or cured meats. In the Southern parts of the Atlantic region, Grits are served with Shrimp, in the quintessential “Shrimp and Grits.” Leftover grits can then be fried in animal fat to make “Grit Cakes.”

The Atlantic Regions are very well known for seafood, with crabs, clams, oysters, and haddock being served near the shore. Most times, this seafood is fried, and served with a tartare sauce, but can also be prepared in fried cakes, most famous of which are crab cakes. In the Tidewaters of the Carolinas and of Georgia, people eat stews in social gatherings very similar to the “boils” of Louisiana, usually involving shrimp, corn on the cob, sausage, red potatoes, sometimes ham. Known variously as Frogmore Stew, a Beaufort boil, a Lowcountry boil, or a tidewater boil, they tend to be a bit milder than their Louisiana cousins. Frog legs are eaten throughout the south, and considered a delicacy.

Stews tend to be relatively common away from the coasts as well. In the colder months, they are thick, hearty, most often prepared with root vegetables and small game meat.

Sausages are incredibly common throughout the region, with all kinds of meat (Anything from Beef and Pork to wild game to snake and even alligator) and flavorings making their way into the hog casings. Unlike sausages in many other parts of the world, Confederate Sausages almost always have both meat as well as a fruit (usually cooked apples or dried berries) to sweeten the meat.

Chicken also holds a soft place in the hearts of southerners, being prepared in soups, with thick bready “dumplings,” or being breaded and deep fried in oil. It is also not uncommon for whole chicken to be seasoned inside and out, placed on a rotating skewer, and roasted over an open flame.

The Flora of the Deep South Region, culinarily speaking, is also quite varied. Confederate Farmers produce a large variety of greens, vegetables, roots, and Fruit. Perhaps one of the most well known vegetable dishes are “Collard Greens,” which has spread from the slave quarters of backwoods plantations into the highest restaurants of Savannah. Large leafy greens (Sometimes mixed with or replaced with other leafy greens like Kale, Turnip Greens, or Swiss Chard, cooked with a small amount of a salty, fatty meat (Such as Ham Hock, Turkey Necks, or Bacon) as well as a bit of vinegar, sugar, salt, and spices. Corn on the Cob is often served as well, though rarely in the homes of the wealthy. It is often roasted over an open flame or boiled, then slathered with butter, salt, and sometimes spice, and then eaten, the soft and sweet kernels bitten off the hard, inedible core. Tomatoes, Onions, Ramps, and Okra are also commonly found on plates across the south, either as part of another dish, or sliced and served raw. (Even the Sweet vidalia onions can be served sliced and raw.)

Nuts abound in the Deep South, both tree nuts and ground nuts. Peanuts were native to the Americas. The most common use, however, originates with African Slaves, who replaced in their recipes a similar nut common in west africa with the peanut. The most obvious example of these is the Peanut Soup, which is served hot in the slave huts and cold in the plantation houses. Peanuts are also boiled and eaten soft, Roasted and salted, or even deep-fried. Tree nuts, such as Walnuts, Pecans, and Almonds, can be served candied, or ground into a breading for catfish or pork, or made into the filling for a pie.

Many Root vegetables are grown in the south, and served in different ways depending on the variety. Carrots are often lightly candied, cooked in butter and brown sugar and served as an accompaniment to meats, while potatoes and other tubers are often roasted or mashed.

Fruit truly showcases the variety of foods in the deep south, from sweet and crisp apples in the north to the juicy peaches of Georgia to apricots and fig groves in Alabama, to berries and melons in gardens nationwide. The Pawpaw of the atlantic coast is a delicate fruit that most outside of the region will never try, as it will not ship, but is unique in many ways, a strange combination of custard, mango, and banana. The Maypaw of the southern bayous is known to produce the most delicious jam in the world, while the American Persimmon, distinct from its asian counterpart, does not bear the same astringency, but instead has a taste like that of a firm apricot. The Japanese Lowcat has recently spread from New Orleans into orchards of Alabama and Mississippi, and, though the fruit is still a novelty, it has found it’s place in the repertoire of many a confederate housewife, in Jams, in Tarts, in Fruit Salads, even in buckets of moonshine and hooch.

While unfortunately for many outside of the CSA, most varieties of native fruit are too delicate to ship, and so are impossible to taste fresh, fortunately, one of the keenest culinary traditions of the south are preserves: fruit boiled with sugar until the natural pectins within make a thick and gelatinous. While every housewife has her own recipe for preserves, there are some traits that unify most confederate preserves, both those produced at home and those produced commercially. Confederate preserves are known for their relatively large chunks of fruit and relative purity: It is rare for a confederate preserve to mix different varieties of fruit. By the last decade of the 1800s, confederate preserves were being exported and sold almost around the world. Japan became a ready market, as did Italy, Poland, and Great Britain, sailors enjoying the fruit flavors after weeks at sea.

The Deep south has a soft spot for desserts and sweets. Perhaps the most ubiquitous of these delicacies of the South is the Pie. Pecan, Sugar, Molasses, or Fruit, pie recipes are as numerous as the cooks of the south. Everyone, from the poor backwoods grandmother, to the free black woman to the plantation’s house cook, has her own recipe she swears by, her own pie dough proportions (butter, flour, salt, and water can be combined in myriads of different ways), her own fillings, and her own method for covering the pie, whether it’s a lattice of dough, a simple flat layer covering the filling, an intricate construction of dough, or even a bare top.

Similar to pies, cobblers (and crisps and crumbles) fill an important role in confederate deserts. Less common amongst the elite, the cobbler is a symbol of the poor white farmer or factory worker. Cobblers consist of a few layers of fruit (often peach, apple, lowcat, or berries) baked with a layer of dough. Crisps and crumbles mix oats into the batter.

Despite the position pies and cobblers hold in the confederate zeitgeist, they are by no means the only sweet. In Kentucky, for example, cream candies are common, similar to the Tire of Quebec, or the Taffy of the North East. Confederate chocolatiers work with Bourbon, Cordials, and Candied fruit to make truffles, and Divinity, a nougat-like sweet made from Corn (or Cane) syrup, egg whites, sugar, and sometimes milk. Puddings also abound as desserts, often in the poorer regions. Unrecognizable to a traveling Brit hoping for more familiar cakelike pudding, Confederate (and American puddings as a whole) are much creamier. Confederates enjoy corn, banana, chocolate, chickory, and rice puddings, all of which are often eaten cool, or cold.

New Orleans/Mississippi:

New Orleans is the most diverse area of the confederacy, an interface of cultures so different it’s a wonder they get along. Spanish, Anglo-American, Caribbean Creole, Cajun, Japanese, and African cultures meld and mesh, and their cuisines have synthesized into something unique in the world.

The first European Settlers in New Orleans were the French, in the late 18th century, and by the time the spanish took dominion of the region, and intermingled with the french and african slaves that both had brought, a distinct Creole identity had been created, a fusion of their respective flavor profiles. Like Spanish and French Cuisine, Creole cuisine tends to be based on thick and flavorful sauces, though, unlike the french, Creole sauces boast robust flavors drawn from West African seasonings.

Cajun immigrants, acadians from canada, expelled by the british, in the late 18th century, brought their own culinary traditions, also descended from French, though distinct from creole. Eschewing the sharp flavors of their creole cousins, Cajun cuisine tends towards the more Rustic, heavy, hearty foods. Cajun cooks favor garlic, onion, and file powder (itself adopted from local native americans) over more spicy flavorings.

Though the Japanese are recent immigrants to the area, they have already had a significant impact on the cuisine of the new orleans, importing myriads of new ingredients to the area. The Makeup of the early days of the Chrysanthemum district was of a number of rich Japanese merchant families that imported a significant japanese retinue: Laborers, craftsmen, and cooks. Fascinated by the flavors of the deep south, Japanese cooks adapted the local Creole cuisine to Japanese tastes, and vice versa. Sweet Tea found a Green Tea equivalent, and Japanese chefs adapted the noodle soups of their homelands to the ingredients of the area: noodles in thick, fatty broth were made of corn, and became much thicker than those of their homelands, with fried porkchops as the main protein. This “Suimono” became a food of choice amongst laborers, and Fat and sweet ruled king for the chefs of the Japanese district. Japanese-Creole (Or Numajin) cuisine quickly spread outside of the Chrysanthemum district, as enterprising japanese opened restaurants in the docks districts, serving suimono to tired laborers. The Japanese also adopted their traditional fish dishes with local ingredients, oysters (which existed in Japan) supplanting clams (which were much rarer in New Orleans) and Mahi-Mahi replacing Tuna.

Despite its newfound appeal, and aside for one significant, utterly massive change - the replacement of the traditional cornmeal breading with a lighter tempura breading in most dishes aside for chicken, the new Numajin cuisine didn’t dramatically impact the majority of the greater New Orleans community. Most continued to eat what they had been eating for generations.

The most significant food groups in the New Orleans area had always been Seafood. Existing on the interface between a river, a marsh, and the ocean, the people of new orleans had always had access to a wide variety of freshwater and saltwater ingredients.

Shrimp and Oysters are the predominant saltwater Seafoods eaten. Oysters were eaten raw, cracked open and sprinkled with a mignonette sauce, or breaded and fried, or, in the case of many fishermen, skewered raw between chunks of half cooked bacon, and roasted over an open flame. Shrimp, on the other hand, tended to be used in thick stews, whether it be the flavorful creole Gumbo or a simple Boil, or fried and placed in a sandwich. The Freshwaters offered Crawfish (or Mudbugs) and catfish, among others. Catfish is often prepared blackened, a layer of seasoning and spice on the outside, and flash fried in a red-hot cast iron skillet, charring the outside black. Crawfish, on the other hand, has a large variety of different methods of preparation, from a simply boil, with corn and potatoes, to an etouffer, where the crawfish are “drowned” in a thick and spicy roux based sauce, and served over rice or grits.

Gumbo deserves a special mention, being the most famous creole dish of New Orleans. Possibly tracing it’s roots to Choctaw dishes, Gumbo is a thick roux-based stew that uses culinary techniques of Spain, West Africa, France, and, surprisingly, German. First, Meat (usually sausages or ham) is browned, and then taken off the heat, and something similar is done with the Okra. In the pan, then, are placed the Holy Trinity, the aromatics: Onion, Bell Peppers, and Celery. When those are cooked enough, the ingredients for the roux are added. When that thickens, a thick broth is poured over it, and the meat and Okra (and any other vegetables) are added back, and simmered until the meats are tender. As seafood cooks more quickly, and become inedible if added too early, it is added just before the end of the cooking process. Most Gumbos also use File Powder, which is dried leaves of the sassafras tree, and spicy sauces.

The Rice and Beans that exist throughout the Caribbean also have a variant in New Orleans. Red Kidney beans are used instead of the Black Beans of the Antilles, and the array of spices is very different. The Beans are simmered slowly with hocks of ham, or Andouille sausages as well as the Holy Trinity, and then served over white rice.

Sweets play a key role in the cuisine of the New Orleans, as they do in the rest of the south. Beignets, a sweet choux dough that is fried and sprinkled with powdered sugar, are the common weekend breakfasts of most wealthy New Orleans people, and the poor enjoy it in on holidays and special occasions. The Summer heat of New Orleans has also pushed people to create cooler desserts and treats, including the snowball, from ice imported from far away. The ice is shaved roughly and the “snow” is then covered in a sweet fruit syrup, creating a cold desert.

Finally, it’d be impossible to discuss Deserts in New Orleans without discussing the Praline. With it’s roots in the Praline of France, the confection was imported to New Orleans by settlers looking for a taste of “La Patrie.” New Orleans Praline bears some distinction from its ancestor, though, using Almonds instead of Pecans, and with the addition of Cream or Buttermilk to the creation process. The Abundance of Sugar and Almond trees in New Orleans has allowed the Praline to be one of the key candies of the area.

Caribbean:

For the Purpose of this discussion, the Caribbean refers to both the states Acquired during and after the Atlantic War and to Florida, which had been part of the American culinary complex for decades. It is safe to assume that many of the techniques, flavors, and ingredients common in Florida are also common in the States of Antilles, Cuba, and the Bahamian Territories.

The Antilles has a strong dichotomy between two distinct styles that coexist, sometimes even in the same meal. For the sake of ease, these are occasionally referred to as “coastal” and “inland” styles, but, though there is a slight geographic association, one is just as likely to find something like Cocido, emblematic of inland cuisine, on the coast, as one is to find marinated Casava up in the inlands of Antilles or Cuba.

The thousands of miles of coast in the Caribbean region provide a significant portion of the diets of the coast. Fish and shellfish are either cooked quickly over high heat, keeping them light, or “cooked” with lime-juice, creating a ceviche of sorts, such as the bahamian Conch Salad. Cooked dishes are most often served with tropical fruit, either fresh, or prepared in some sort of mildly spicy salsa. The sweet, cool, food helps cut the muggy heat of the southern reaches of the CSA. Aesthetically, the coastal techniques emphasize simple presentation over ostentatious ones.

The Introduction of ingredients from south east asia, through Japan, though still young, has also had an impact, increasing the variety of ingredients, and introducing traditional sushi preparations to coastal farmers, fishermen, and city dwellers.

In contrast, the island foods are heavier, heartier, and made with ingredients readily available to the poor far from the ocean, and which take a while to cook, so that they can be set on the heat in the morning and prepared to eat in the evening. This includes the ever-present Arroz con Gandules, or Rice and Beans, Cocido, Sancocho, Piccadilo, and even Ropa Vieja, which, though similar to the Pulled Pork of the deep south, has a very different flavor profile (it should be noted, however, that much of the elite and even middle class, have adopted the Confederate techniques for many cuisines.)

The Caribbean have a strong cured meat tradition, stemming from the historic spanish rule. Dried sausages, prosciutto, and even cured hams, hybridizing the virginia country ham traditions with the fine cured meats of spain, a Hamon Virginia. Some experts argue that the Hamon Virginia rivals some jamon Ibericos, or even some Jamon Serranos. Dry Sausages, both traditional Caribbean Sausages (Such as as Chorizo, Botifarra, and Andouilles) and Modified American style (with fruit in the mix,) are now common throughout the area, and even exported, as meat that does not spoil even after months of travel is extremely valuable.

There are regional distinctions between the various parts of the Caribbean, of course. Antilles and Cuba have a much greater native american, specifically Taino, influence than either the Bahamas or Florida, while Florida is much closer to the greater American culinary complex. The Native influence in Caribbean Cuisine is best seen in the use of Tubers, most especially Cassava, which is processed and ground to make thin wafer-like crackers. The vast majority of the spices used in Caribbean cuisine were raised by the Taino, as were a large variety of fruit, such as Soursop, Mango, Guavas, and Pineapples, all of which were used extensively. Unlike mainland Native tribes, Maiz was not used commonly, vulnerable as it is to hurricanes. The Original Spanish Colonists as well as the African Slaves who were brought in to replace the Dying Taino, learned much from the Taino, adopting their knowledge to new practices and flavors.

Mofongo is a dish that is quintessentially a hybrid between Taino cuisine and that of West African slaves. In west africa, Fufu is made with any kind of starchy root, but in the Caribbean, Mofongo is exclusively made with plantains, which are mashed and fried, often with salt, pork, and oil.

Caribbean Barbeque, or Barbacoa, is distinct from either other American styles, in that it does not use a sauce, but rather only a Dry Rub. In addition, most Caribbean barbeque is prepared as small chunks of meat (Pork chops, or quartered chickens, or, since the confederate takeover, Turkey) cooked ever a mesh of green shoots or sticks, providing the smoke flavor through the heating of the wet wood. Barbaoa, or Lehon, is also common, and consists of a whole animal, split down the belly and slowly roasted in a pit over an open flame, which is then covered with banana leaves, retaining heat. This tends to be a social event, with whole villages getting together with more than one animal being grilled.

Breads and Pastries are also extremely common throughout the Islands, and through migrants, to Florida, which does not itself have much of a baking tradition. Bread in the Islands comes from Cuba, their techniques supplanting whatever may have existed before it’s introduction. Cuban Breads are long and thin, with a hard, thing, flaky crust and a soft interior. It’s distinctive air pockets are a relic of the stretching process, which was designed to make less dough create more bread. Before the baking process, a wet palmetto frond is laid across the top and removed after, creating a depression similar to that caused by the slashing of European style loafs. Many sandwiches use this bread, though, unlike the laborers of the Continental CSA, they are not the food of choice for laborers bringing lunch into the field or factory. Instead, Caribbean laborers eat empanadas, deep fried packets of flaky dough, with a delicious filling inside. The insides are as varied as the people who eat them, using leftover meats, vegetables, cheeses, and even fruit. Though best when eaten fresh, they are still good later in the day.

Desserts in the Caribbean also follow the dichotomy expressed by the rest of it’s cuisine. Many people simply drink fresh fruit or cane juice, cooling and sweet. At the other end of the spectrum is Dulce de Leche, a sweet made through slowly reducing milk, so that it concentrates and caramelizes. Some regions add some spices to the process, and others add honey, but the bulk of the flavor will come from the caramelization of the milk sugars. Pastelitos are also common throughout the region. These baked puff-pastry recipes are traditionally filled with a slightly sweetened cream cheese and with a fruit paste, usually guava, but occasionally pinapple, mango, or soursop. Lychee, introduced by the Japanese, is also being increasingly used.

Southwest:

Like the food of the Caribbean, the food in the Southwest has two distinct regions. The first is Texan, which is a hybrid of Mexican cuisine and of Deep South. The Second is Cherokee. Though there are ingredients in common, the two do not readily mix.

Texas is the heartland of the third great Barbeque Tradition. Unlike either of the other two, Texan BBQ focuses primarily on beef, and most specifically, on the Beef Brisket, which is often seasoned with a dry rub and smoked slowly in a pit. Almost as common are beef ribs, which tend to be slathered in a thick molasses based sauce and smoked over mesquite until the meat practically falls off the bone. In the south of Texas, near the border with Mexico, Ranch Hands also developed a third technique. Often paid with lesser cuts of meat (such as the Head or Diaphragm of the cow) Texan ranchers cook the meat the same way mexican Rancheros on the other side of the border do. They would wrap the Head in wet agave leaves after seasoning it and buried in a pit of hot coals for a few hours. The meat would fall off the bone, and often would be eaten on a tortillas. Unlike in the rest of the CSA, BBQ is not served with coleslaw.

The Head “barbacoa” is not the only mexican influence on texan cuisine. Ranch hands prepare arrachetas from the Diaphragm, again a cheap meat, of the cow, frying it on a skillet with onions and peppers. This is then wrapped in a corn tortilla and easily eaten on the road. Other “Tex-Mex” foods include tamales, burritos, chimichangas, and quesadillas, all foods that are relatively easy to carry out on the range. This practicality without sacrificing flavor is common amongst texans, and perhaps evidenced in what has quickly become the most quintessentially texan food.

The Hamburger, a fried meat patty served with mustard and onion between two halves of a brioche bun, and with a pickle on the side, now recognizable in almost all cities of the CSA, was invested in Athens Texas by a man named Fletcher Davis. So named, he claims, for its relation to german meat patties, introduced to the CSA by German investors and laborers, the Hamburger is both delicious and filling, allowing a man to work long hours and enjoy his meal on the go. Though the first hamburgers were sold between two slices of bread, and in many places still are, the development of the “Hamburger bun” made this portable meal even more portable.

Cherokee cuisine, on the other hand, tends towards simple and rustic, and focuses on the “three sisters” emblematic of Native American Agriculture: Corn, beans, and Squash. Often, corn would be ground and made into cakes, which were grilled on an open flame, similar to the Arepas of South America. Meats, hunted and domesticated, including rabbit, deer, pork, and Turkey, are often also grilled. (Some records indicate that Turkey was being domesticated by the ancestors of the Cherokee nearly a millenia ago.)

Apples play a large part in cherokee cuisine, eaten fresh, dried, or baked in pies and tart. Berries are also an important part of their flavor profile, providing tartness and sweetness that is otherwise hard to come by. Cherokee children enjoy as a treat Kamanuchi, a dessert made with hickory nuts. The nuts are allowed to dry, then pounded into a rough paste, which is then allowed to dry, before being boiled until it has the consistency of thick cream, and used to prepare a sweet hominy or rice porridge.

Cherokee cuisine, however, is starting to fade, as the Cherokee have taken strongly to the Cuisine of the deep south.

Other:

There are two regions that are not impactful enough to the greater Confederate Culinary complex, but still unique enough to merit discussion.

The Foods of the Appalachian Mountains are similar at first glance to that of the rest of the deep south, but, upon closer inspection prove to be unique and remarkable. Appalachian cooks make do with what they have to produce meals of incredible complexity. Fermentation is often used, making Sauerkraut from cabbage, as well as “leather britches” long beans, sour corn from corn, and even fermented beans. The fermentation adds a layer of complexity, while allowing the food to be preserved for much longer.

That instinct for preservation is key to survival in the appalachians, as the short growing season meant that all foods need to be preserved in one manner or another. Meat, even small game like squirrel and raccoon, is smoked, and fruit are turned into Jams and Jellies. Apples are made into Apple Butter.

Finally, the most unique traits of appalachia cuisine is salt. Brine drawn from deep underground is allowed to dry, forming a pure white crystal with a cleaner flavor than salt produced from the ocean.

The Food of Gabon is a hybrid of Portuguese, Deep South, and West African. The relative social mobility of the Gabon colonies has allowed the melding of their respective foods. Chickens are roasted and smoked with Southern and African spices, and beignets are eaten with condensed coconut milk. Atlantic Style Barbeque has spread to the Gabon, but instead of wine or cider vinegar, it is palm that is used to make the sauce, and Seafood is blackened or made into stews, as do the people of New Orleans.

The Deep South:

It is often said that the border with Maryland is the last place one can get good barbeque, though, undoubtedly there are some to the north who would disagree. The Confederate States boast three distinct styles of Barbeque, one of which is centered in North Carolina. Almost exclusively pork based, Atlantic Style Barbeque is known for vinegar based sauces, varying from almost exclusively vinegar in the east to a more robust tomato and spicy-sweet sauces towards the west. The cuts of meat usually barbequed are the Ribs, on the rack, and Butts (shoulder,) which makes a pulled pork, usually eaten in sandwiches. On special occasions, rural farmers may get together for a “pig-pickin’” where a whole pig is roasted in a pit.

Some regions of Virginia are well known for their Country Hams, which are protected by state law. These hams are salt-cured, and then smoked with cherry or apple wood, and finally left to age for anywhere between a few months and three years. Country hams are often cooked by boiling in several changes of water, and then pan frying lightly, just enough to brown the exteriors and warm up the meat. Some purists insist that the dry, salty, moldy crust must be eaten, but most people agree that the harder edges must be pared off before eaten. Often times, a red-eye gravy will be prepared with the drippings, as well as some Grits.

Hominy Grits, or just grits, may be the most quintessential culinary offering of the CSA, bar none, and nowhere is this more true than in the Atlantic and Deep south regions of the nation. Grits are, at it’s most fundamental, dried corn treated with Alkali and with the germ removed. These are ground, traditionally on a stone wheel, and prepared by boiling for in 5-6 times their volume in liquid, traditionally salted water or broth, but occasionally milk. They are typically seasoned with salt and pepper, and generous amounts of butter, but occasionally, grits are prepared with cheese, or with some sort of cooked or cured meats. In the Southern parts of the Atlantic region, Grits are served with Shrimp, in the quintessential “Shrimp and Grits.” Leftover grits can then be fried in animal fat to make “Grit Cakes.”

The Atlantic Regions are very well known for seafood, with crabs, clams, oysters, and haddock being served near the shore. Most times, this seafood is fried, and served with a tartare sauce, but can also be prepared in fried cakes, most famous of which are crab cakes. In the Tidewaters of the Carolinas and of Georgia, people eat stews in social gatherings very similar to the “boils” of Louisiana, usually involving shrimp, corn on the cob, sausage, red potatoes, sometimes ham. Known variously as Frogmore Stew, a Beaufort boil, a Lowcountry boil, or a tidewater boil, they tend to be a bit milder than their Louisiana cousins. Frog legs are eaten throughout the south, and considered a delicacy.

Stews tend to be relatively common away from the coasts as well. In the colder months, they are thick, hearty, most often prepared with root vegetables and small game meat.

Sausages are incredibly common throughout the region, with all kinds of meat (Anything from Beef and Pork to wild game to snake and even alligator) and flavorings making their way into the hog casings. Unlike sausages in many other parts of the world, Confederate Sausages almost always have both meat as well as a fruit (usually cooked apples or dried berries) to sweeten the meat.

Chicken also holds a soft place in the hearts of southerners, being prepared in soups, with thick bready “dumplings,” or being breaded and deep fried in oil. It is also not uncommon for whole chicken to be seasoned inside and out, placed on a rotating skewer, and roasted over an open flame.

The Flora of the Deep South Region, culinarily speaking, is also quite varied. Confederate Farmers produce a large variety of greens, vegetables, roots, and Fruit. Perhaps one of the most well known vegetable dishes are “Collard Greens,” which has spread from the slave quarters of backwoods plantations into the highest restaurants of Savannah. Large leafy greens (Sometimes mixed with or replaced with other leafy greens like Kale, Turnip Greens, or Swiss Chard, cooked with a small amount of a salty, fatty meat (Such as Ham Hock, Turkey Necks, or Bacon) as well as a bit of vinegar, sugar, salt, and spices. Corn on the Cob is often served as well, though rarely in the homes of the wealthy. It is often roasted over an open flame or boiled, then slathered with butter, salt, and sometimes spice, and then eaten, the soft and sweet kernels bitten off the hard, inedible core. Tomatoes, Onions, Ramps, and Okra are also commonly found on plates across the south, either as part of another dish, or sliced and served raw. (Even the Sweet vidalia onions can be served sliced and raw.)

Nuts abound in the Deep South, both tree nuts and ground nuts. Peanuts were native to the Americas. The most common use, however, originates with African Slaves, who replaced in their recipes a similar nut common in west africa with the peanut. The most obvious example of these is the Peanut Soup, which is served hot in the slave huts and cold in the plantation houses. Peanuts are also boiled and eaten soft, Roasted and salted, or even deep-fried. Tree nuts, such as Walnuts, Pecans, and Almonds, can be served candied, or ground into a breading for catfish or pork, or made into the filling for a pie.

Many Root vegetables are grown in the south, and served in different ways depending on the variety. Carrots are often lightly candied, cooked in butter and brown sugar and served as an accompaniment to meats, while potatoes and other tubers are often roasted or mashed.

Fruit truly showcases the variety of foods in the deep south, from sweet and crisp apples in the north to the juicy peaches of Georgia to apricots and fig groves in Alabama, to berries and melons in gardens nationwide. The Pawpaw of the atlantic coast is a delicate fruit that most outside of the region will never try, as it will not ship, but is unique in many ways, a strange combination of custard, mango, and banana. The Maypaw of the southern bayous is known to produce the most delicious jam in the world, while the American Persimmon, distinct from its asian counterpart, does not bear the same astringency, but instead has a taste like that of a firm apricot. The Japanese Lowcat has recently spread from New Orleans into orchards of Alabama and Mississippi, and, though the fruit is still a novelty, it has found it’s place in the repertoire of many a confederate housewife, in Jams, in Tarts, in Fruit Salads, even in buckets of moonshine and hooch.

While unfortunately for many outside of the CSA, most varieties of native fruit are too delicate to ship, and so are impossible to taste fresh, fortunately, one of the keenest culinary traditions of the south are preserves: fruit boiled with sugar until the natural pectins within make a thick and gelatinous. While every housewife has her own recipe for preserves, there are some traits that unify most confederate preserves, both those produced at home and those produced commercially. Confederate preserves are known for their relatively large chunks of fruit and relative purity: It is rare for a confederate preserve to mix different varieties of fruit. By the last decade of the 1800s, confederate preserves were being exported and sold almost around the world. Japan became a ready market, as did Italy, Poland, and Great Britain, sailors enjoying the fruit flavors after weeks at sea.

The Deep south has a soft spot for desserts and sweets. Perhaps the most ubiquitous of these delicacies of the South is the Pie. Pecan, Sugar, Molasses, or Fruit, pie recipes are as numerous as the cooks of the south. Everyone, from the poor backwoods grandmother, to the free black woman to the plantation’s house cook, has her own recipe she swears by, her own pie dough proportions (butter, flour, salt, and water can be combined in myriads of different ways), her own fillings, and her own method for covering the pie, whether it’s a lattice of dough, a simple flat layer covering the filling, an intricate construction of dough, or even a bare top.

Similar to pies, cobblers (and crisps and crumbles) fill an important role in confederate deserts. Less common amongst the elite, the cobbler is a symbol of the poor white farmer or factory worker. Cobblers consist of a few layers of fruit (often peach, apple, lowcat, or berries) baked with a layer of dough. Crisps and crumbles mix oats into the batter.

Despite the position pies and cobblers hold in the confederate zeitgeist, they are by no means the only sweet. In Kentucky, for example, cream candies are common, similar to the Tire of Quebec, or the Taffy of the North East. Confederate chocolatiers work with Bourbon, Cordials, and Candied fruit to make truffles, and Divinity, a nougat-like sweet made from Corn (or Cane) syrup, egg whites, sugar, and sometimes milk. Puddings also abound as desserts, often in the poorer regions. Unrecognizable to a traveling Brit hoping for more familiar cakelike pudding, Confederate (and American puddings as a whole) are much creamier. Confederates enjoy corn, banana, chocolate, chickory, and rice puddings, all of which are often eaten cool, or cold.

New Orleans/Mississippi:

New Orleans is the most diverse area of the confederacy, an interface of cultures so different it’s a wonder they get along. Spanish, Anglo-American, Caribbean Creole, Cajun, Japanese, and African cultures meld and mesh, and their cuisines have synthesized into something unique in the world.

The first European Settlers in New Orleans were the French, in the late 18th century, and by the time the spanish took dominion of the region, and intermingled with the french and african slaves that both had brought, a distinct Creole identity had been created, a fusion of their respective flavor profiles. Like Spanish and French Cuisine, Creole cuisine tends to be based on thick and flavorful sauces, though, unlike the french, Creole sauces boast robust flavors drawn from West African seasonings.

Cajun immigrants, acadians from canada, expelled by the british, in the late 18th century, brought their own culinary traditions, also descended from French, though distinct from creole. Eschewing the sharp flavors of their creole cousins, Cajun cuisine tends towards the more Rustic, heavy, hearty foods. Cajun cooks favor garlic, onion, and file powder (itself adopted from local native americans) over more spicy flavorings.

Though the Japanese are recent immigrants to the area, they have already had a significant impact on the cuisine of the new orleans, importing myriads of new ingredients to the area. The Makeup of the early days of the Chrysanthemum district was of a number of rich Japanese merchant families that imported a significant japanese retinue: Laborers, craftsmen, and cooks. Fascinated by the flavors of the deep south, Japanese cooks adapted the local Creole cuisine to Japanese tastes, and vice versa. Sweet Tea found a Green Tea equivalent, and Japanese chefs adapted the noodle soups of their homelands to the ingredients of the area: noodles in thick, fatty broth were made of corn, and became much thicker than those of their homelands, with fried porkchops as the main protein. This “Suimono” became a food of choice amongst laborers, and Fat and sweet ruled king for the chefs of the Japanese district. Japanese-Creole (Or Numajin) cuisine quickly spread outside of the Chrysanthemum district, as enterprising japanese opened restaurants in the docks districts, serving suimono to tired laborers. The Japanese also adopted their traditional fish dishes with local ingredients, oysters (which existed in Japan) supplanting clams (which were much rarer in New Orleans) and Mahi-Mahi replacing Tuna.

Despite its newfound appeal, and aside for one significant, utterly massive change - the replacement of the traditional cornmeal breading with a lighter tempura breading in most dishes aside for chicken, the new Numajin cuisine didn’t dramatically impact the majority of the greater New Orleans community. Most continued to eat what they had been eating for generations.

The most significant food groups in the New Orleans area had always been Seafood. Existing on the interface between a river, a marsh, and the ocean, the people of new orleans had always had access to a wide variety of freshwater and saltwater ingredients.

Shrimp and Oysters are the predominant saltwater Seafoods eaten. Oysters were eaten raw, cracked open and sprinkled with a mignonette sauce, or breaded and fried, or, in the case of many fishermen, skewered raw between chunks of half cooked bacon, and roasted over an open flame. Shrimp, on the other hand, tended to be used in thick stews, whether it be the flavorful creole Gumbo or a simple Boil, or fried and placed in a sandwich. The Freshwaters offered Crawfish (or Mudbugs) and catfish, among others. Catfish is often prepared blackened, a layer of seasoning and spice on the outside, and flash fried in a red-hot cast iron skillet, charring the outside black. Crawfish, on the other hand, has a large variety of different methods of preparation, from a simply boil, with corn and potatoes, to an etouffer, where the crawfish are “drowned” in a thick and spicy roux based sauce, and served over rice or grits.

Gumbo deserves a special mention, being the most famous creole dish of New Orleans. Possibly tracing it’s roots to Choctaw dishes, Gumbo is a thick roux-based stew that uses culinary techniques of Spain, West Africa, France, and, surprisingly, German. First, Meat (usually sausages or ham) is browned, and then taken off the heat, and something similar is done with the Okra. In the pan, then, are placed the Holy Trinity, the aromatics: Onion, Bell Peppers, and Celery. When those are cooked enough, the ingredients for the roux are added. When that thickens, a thick broth is poured over it, and the meat and Okra (and any other vegetables) are added back, and simmered until the meats are tender. As seafood cooks more quickly, and become inedible if added too early, it is added just before the end of the cooking process. Most Gumbos also use File Powder, which is dried leaves of the sassafras tree, and spicy sauces.

The Rice and Beans that exist throughout the Caribbean also have a variant in New Orleans. Red Kidney beans are used instead of the Black Beans of the Antilles, and the array of spices is very different. The Beans are simmered slowly with hocks of ham, or Andouille sausages as well as the Holy Trinity, and then served over white rice.

Sweets play a key role in the cuisine of the New Orleans, as they do in the rest of the south. Beignets, a sweet choux dough that is fried and sprinkled with powdered sugar, are the common weekend breakfasts of most wealthy New Orleans people, and the poor enjoy it in on holidays and special occasions. The Summer heat of New Orleans has also pushed people to create cooler desserts and treats, including the snowball, from ice imported from far away. The ice is shaved roughly and the “snow” is then covered in a sweet fruit syrup, creating a cold desert.

Finally, it’d be impossible to discuss Deserts in New Orleans without discussing the Praline. With it’s roots in the Praline of France, the confection was imported to New Orleans by settlers looking for a taste of “La Patrie.” New Orleans Praline bears some distinction from its ancestor, though, using Almonds instead of Pecans, and with the addition of Cream or Buttermilk to the creation process. The Abundance of Sugar and Almond trees in New Orleans has allowed the Praline to be one of the key candies of the area.

Caribbean: