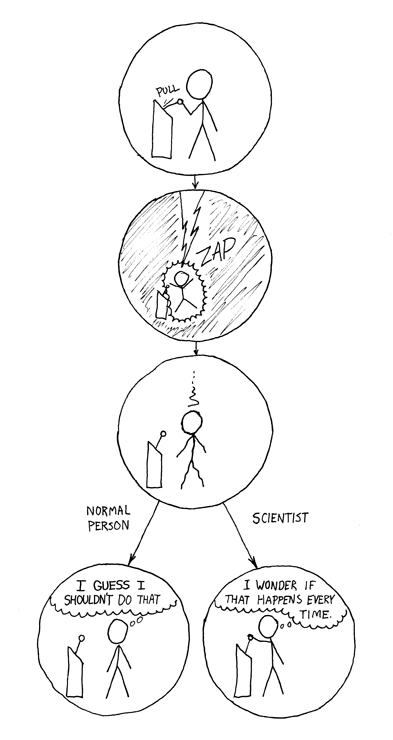

To the cartoon. I had a philosophy professor in college who would very pointedly look at the lights every time he turned on the light switch, as though no number of instances of the lights coming on when he flipped the switch would convince him that the next time it would be true too.

That's not totally unreasonable if you're in an area or situation where power outages can happen, or other strange things.

True story from one of the many science fiction conventions I attended in Calgary in the '80s and '90s:

Saturday afternoon, I'm in my hall costume (long black dress, head covering, black cape, silver jewelry, various other things such as those you'd find in a Larry Elmore painting of magic users, though I drew the line at skulls and bones; I did have feathers), and someone comes up to me, confidently stating that I must be part of the "spiral dance" panel coming up in a few minutes. (the term "cosplay" hadn't been coined yet)

I said no, I didn't even know what a "spiral dance" was. I was headed to the panel titled "Are These the Dark Ages?".

She argued with me; apparently people involved in "spiral dance" dress like Larry Elmore paintings? (though I was more covered up than his female subjects tend to be).

Anyway, she went to her panel, I went to mine. When we all got settled in our chairs, the moderator began by saying, "So. ARE these the Dark Ages?" (in the sociopolitical sense; this was not likely to be a discussion of what some refer to as the Dark Ages when they mean the Middle Ages, which weren't as "dark" as popular perception thinks they were)

BOOM. Out went the lights. We were literally in the dark. Thing is, nobody had been near the light switches (this was in a hotel). Everyone was either sitting down in the audience or up on the platform where the moderator and panelists sat.

What likely happened was an accident. We decided to blame it on the spiral dance panel next door, since they had turned off the lights for their panel (not sure if they used battery-powered candles or real ones).

To this day I don't know why the lights went out like that. It wasn't a practical joke, since nobody was close enough to have switched them off at that exact moment. But it did provide us with a memorable hour or so.