Second and third certainly do - secundus and tertius respectively. 'First' in Latin is primus, while it's 'erst' in German, so suspect that's more likely where it came from. As to why the first couple of numbers are irregular, that probably has something to do with how often we use them. Irregular verbs, by comparison, are usually the most common ones.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

History Questions Not Worth Their Own Thread VIII

- Thread starter Flying Pig

- Start date

sophie

Break My Heart

Third is Germanic in origin, cf. OE þridda, and its Gmc. relatives that went þ->d, eg. German: dritte, Dutch: derde, etc.

Second is, as you noted, French via Latin, the past participial form of sequor ("I follow").

First is also of Germanic origin. It's a superlative form of fore (as in "front", cf. "foremost"). Fore+est = first. The German erst is similar, taking the Germanic root word meaning "early" and putting it in a superlative form.

Second is, as you noted, French via Latin, the past participial form of sequor ("I follow").

First is also of Germanic origin. It's a superlative form of fore (as in "front", cf. "foremost"). Fore+est = first. The German erst is similar, taking the Germanic root word meaning "early" and putting it in a superlative form.

Last edited:

Traitorfish

The Tighnahulish Kid

English is such a beautiful mess.

SS-18 ICBM

Oscillator

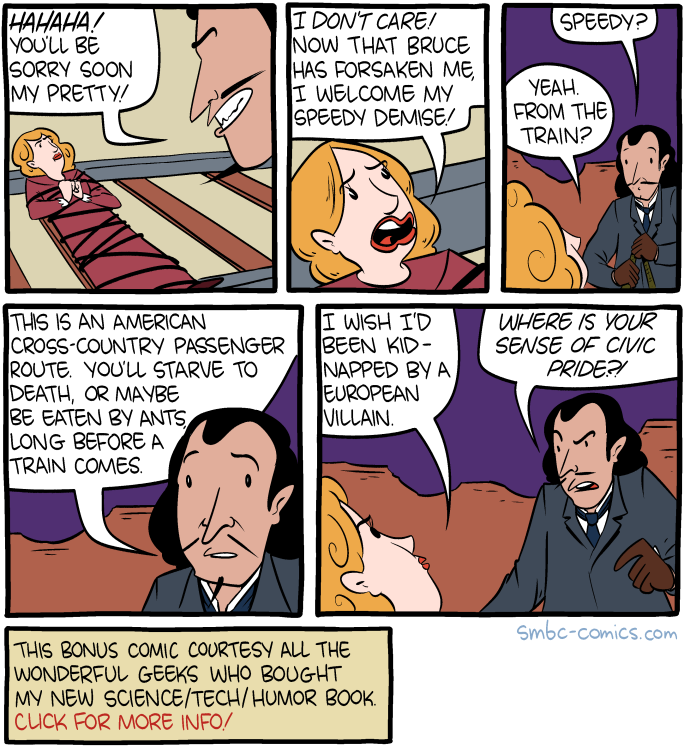

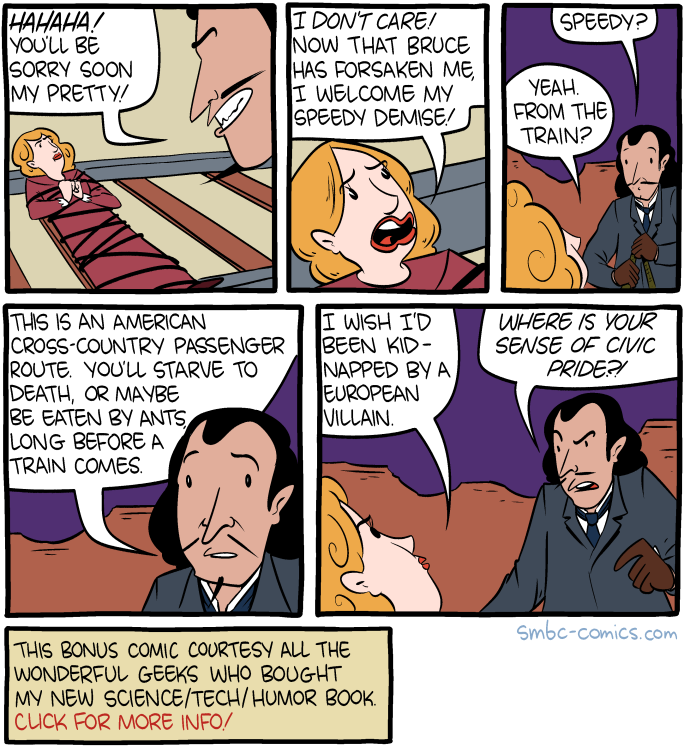

Did trains in the American frontier really only run every few months or so?

Gori the Grey

The Poster

- Joined

- Jan 5, 2009

- Messages

- 13,498

Have any of you read an estimate of the number of languages spoken in the regions covered by the Achaemenid Empire?

I'm looking at a map of the various satrapies and wondering how many of them represented distinct language units.

I'm looking at a map of the various satrapies and wondering how many of them represented distinct language units.

sophie

Break My Heart

Have any of you read an estimate of the number of languages spoken in the regions covered by the Achaemenid Empire?

I'm looking at a map of the various satrapies and wondering how many of them represented distinct language units.

Languages worked very differently then than they do now.

Absolution

King

In the furthest edges of distinction it is true. You don't have to go that much backwards - until the 19th century, the meaning of "language" in many areas of Europe was quite a different thing compared to now (the national-standard era).Languages worked very differently then than they do now.

But still, in order to answer the question above you can narrow it to lower levels in the branches of language families.

Say, instead of replying "Spoken languages were Franconian, Saxon, Tuscan and Genoese", you'll reply "West Germanic and Insular Romance languages were popular at the time".

We should ask ourselves:

1. Was the Persian language (of that era) a unified language?

2. Was that kind (or variants) of Persian language the official/court language of the whole empire?

3. Was it spoken by common residents anywhere outside of proper Parsa region?

4. What other languages were preserved as more than a spoken language of ethnic communities within the Persian borders?

5. Which peoples retained their spoken languages under the Persian rule?

From my limited knowledge:

- Aramaic language was the preferred "diplomatic" language by Persian rulers and was the popular language for international affairs and documentation at the time.

- Written texts in Judaea and Egypt show some kind of presence of their ethnic languages under the Persian rule.

- I assume that Akkadian and it's related languages didn't fade away so quickly after the collapse of the coral Mesopotamian regimes.

- I am actually mostly fascinated about the other frontiers of the empire - did Medes and other Iranians retain their language? Did Lydians and other Asia-Minor nations do so?

sophie

Break My Heart

That might well be true, but it doesn't actually answer his question.

It does in that "languages" in the pre-modern era were quite simply unquantifiable. Depending on how you define a language there could have been one "Persian" language (whether you categorized that as the dialect of Persian spoken among the elite, or you define "Persian" so broadly that you're effectively commenting on what today would be an entire language family) or there could be untold thousands of local dialects all as distinct from village to village as Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian are to us.

Language simply didn't exist as a unified pan-national all-encompassing element of identity as it has in the post nation-state, post-prescriptivist grammar, post-compulsory universal educational environment of today.

Last edited:

Absolution

King

I don't have the wider knowledge about it, but I'll try to challenge this:

Don't you think that statement is mostly Euro-centric?

Language simply didn't exist as a unified pan-national all-encompassing element of identity as it has in the post nation-state, post-prescriptivist grammar, post-compulsory universal educational environment of today.

Don't you think that statement is mostly Euro-centric?

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

No

innonimatu

the resident Cassandra

- Joined

- Dec 4, 2006

- Messages

- 15,377

- I am actually mostly fascinated about the other frontiers of the empire - did Medes and other Iranians retain their language? Did Lydians and other Asia-Minor nations do so?

I think you can safely assume that most regions retained their per-existing languages. Language changes very slowly unless a whole population is replaced. And that too is a rare event.

sophie

Break My Heart

I don't have the wider knowledge about it, but I'll try to challenge this:

Don't you think that statement is mostly Euro-centric?

This.

We can surely do better than two one-word answers!

I'm not a linguist, but I suspect the 'eurocentric' rub is more in the notion that languages are today a 'unified pan-national encompassing element of identity'. Look at any number of African countries, for example - South Africa has eleven official languages and sings its national anthem in five. English is only a kind of lingua franca, and speaking English is not part of South African identity - in fact, I've met plenty of people out there who can barely understand it.

I'm not a linguist, but I suspect the 'eurocentric' rub is more in the notion that languages are today a 'unified pan-national encompassing element of identity'. Look at any number of African countries, for example - South Africa has eleven official languages and sings its national anthem in five. English is only a kind of lingua franca, and speaking English is not part of South African identity - in fact, I've met plenty of people out there who can barely understand it.

Gen.Mannerheim

Grand Moff

Written texts in Judaea and Egypt show some kind of presence of their ethnic languages under the Persian rule.

By the 6th century BC the Hebrews had already begun the shift to using Aramaic as a daily & elite language while keeping Hebrew as a religious one. This happened during the Babylonian Conquest and meant that when the Achaemenids let the Jews return to Judaea Aramaic usage flooded the region. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the elite and educated Jews used Greek (like the majority of the Eastern Mediterranean) with Aramaic as the common tongue.

Its an interesting situation that for most of the history of the Jewish/Hebrew peoples, Hebrew wasn't the common spoken language. The rebirth of Hebrew in Israel in the 20th century quite a singular event in linguistic history, and was only really possible on such a scale because of the need to incorporate Jews from numerous languages into one citizenry. Hebrew was chosen over Yiddish after WWII because, even though ~85% of Jews spoke some level of Yiddish, it was just too "German".

sophie

Break My Heart

We can surely do better than two one-word answers!

I'm not a linguist, but I suspect the 'eurocentric' rub is more in the notion that languages are today a 'unified pan-national encompassing element of identity'. Look at any number of African countries, for example - South Africa has eleven official languages and sings its national anthem in five. English is only a kind of lingua franca, and speaking English is not part of South African identity - in fact, I've met plenty of people out there who can barely understand it.

Bah, really I'm just kinda lazy right now, but that's really not it either. Basically the paradigm upon which people think about languages is wrong. Well, not wrong; it works to an extent in the modern day, and it works historically if you're just talking about the literate elite class of any given region, but otherwise it is wrong.

So here's how you have to think about it:

1) If you know anything about Germany, think about Germany pre-1950. Essentially there were two "Germans" spoken in any given region. There was Hochdeutsch which was the proper, formal German that was spoken on the radio and on tv, in formal political addresses, and in writing. If you took German as a foreign language, this was the German you were taught. Then there was the local dialect. Every village had a local dialect distinct to the village through which locals communicated with one another, and which you almost never taught to outsiders. This dialect was related to Hochdeutsch, sure, but it was decidedly its own thing, linguistically speaking. And although the village dialects were close enough that someone from, say München could communicate with someone from Nürnberg, once you get further afield to into Styria or Sachsen those village dialects no longer become mutually intelligible.

2) The above is what is called a linguistic continuum. To better envision what this is, consider this second, more relatable example. So let's say today, in the year 2017, you start on the west coast of Sicily. You find some random villager (villager A) walking around, and task him with going to the next town over and talking with somebody over there to see if the version of Sicilian villager A uses is mutually intelligible with the Sicilian spoken by a villager B. Villager A walks to the next town, talks to villager B, and finds that, yes, Village A Sicilian and Village B Sicilian are mutually intelligible. Villager B goes to Village C and finds that B and C are mutually intelligible. Now, you can continue this daisy chain from Western Sicily, across the island, across the Strait of Messina, up the boot, through Liguria, through the South of France, over the Pyrenees, through Catalunya, up through Castille, and end at A Coruña, and at no point would that daisy chain be broken. That is- at no point would any given villager be unable to speak with someone from the next village over. Even though in the macro-scale, the Galician of A Coruña is demonstrably, self-evidently different from the Catalunyan of Barcelona, from the Italian of Florence, and from the Sicilian of Messina; at the micro-scale, you would never be able to point out where exactly the Galician ends and the Portuguese or Castilian begins.

That is a linguistic continuum: a continuous geographical stretch of closely related and interlinked dialects that form a band of gradual change. Examples would include the Sicily-Italy-France-Spain-Portugal/Galicia continuum I just mentioned above; the Northern/Western Germanic band of the various German Dialects of Switzerland, Austria, and Germany, plus Plattdeutsch, Nederland; and the North Germanic band of Danish-Swedish-Norwegian, etc. . These continua have faded rather dramatically over the last 200 years due to a) the proliferation of a written grammatic standard, and national, standardized compulsory language education, b) the rise of the nation-states, with national governments legislating the destruction of any and all local and regional dialects in pursuit of a more coherent and consistent national identity, and c) the rapid technological improvements in travel and communication (particularly tv and radio) necessitating and hastening the increased sublimation of local and regional dialects in favor of a more broadly intelligible standard dialect/accent.

However, before those trends started to develop, namely pre-c. 19th century, the continuum was the norm, and it is arguable that the whole of Europe, if not indeed the whole of Eurasia might have been one enormous linguistic continuum. It's important to remember that "language" is only a discrete, definite phenomenon inasmuch as we make it so for the ease of communication (viz: to be able to say "English" rather than "The assorted related dialects spoken in the US, UK, Ireland, Canada, Jamaica, Australia, India, New Zealand, and the various Pidgins spoken in West Africa and the Caribbean") and categorization (because human nature is to make sense of an inherently nonsensical, chaotic world), just as the delineation between species is in biological terms can often be a bit arbitrary and is, at the end of the day, something we apply post-facto for categorization purposes, rather than something that exists inherently in the system. There's no such thing as "Early Modern English" or "Classical Latin"; these are catch-all terms to refer to any hundreds if not thousands of variants and dialects and regionalisms that may have existed over however long is useful to us for the purposes of neat and immediately understandable geographic and historical categorizations. The same can be applied to Language Families. In the abstract Slavic and Germanic are obviously different families, but that is because the standardized, modern descendants that have come to represent these families grew up in geographically and linguistically very distant contexts. If we went to, say 1340, pulled a Brothers Grimm, and simply started documenting the forms of language we were hearing along the Oder, the sorts of dialects we would be hearing would probably not fit quite so neatly into our Linguistic Family archetypes.

We don't think about think these things because they simply aren't the reality that we inhabit today, and it's very easy to forget that linguistic reconstructions are themselves abstractions representing any hundreds upon thousands of different local realities. It certainly also doesn't help that languages, particularly regional and non-aristocratic languages only really started being documented with any kind of academic rigor about 200 years ago.

Last edited:

Gen.Mannerheim

Grand Moff

That is a linguistic continuum: a continuous geographical stretch of closely related and interlinked dialects that form a band of gradual change. Examples would include the Sicily-Italy-France-Spain-Portugal/Galicia continuum I just mentioned above; the Northern/Western Germanic band of the various German Dialects of Switzerland, Austria, and Germany, plus Plattdeutsch, Nederland; and the North Germanic band of Danish-Swedish-Norwegian, etc. . These continua have faded rather dramatically over the last 200 years due to a) the proliferation of a written grammatic standard, and national, standardized compulsory language education, b) the rise of the nation-states, with national governments legislating the destruction of any and all local and regional dialects in pursuit of a more coherent and consistent national identity, and c) the rapid technological improvements in travel and communication (particularly tv and radio) necessitating and hastening the increased sublimation of local and regional dialects in favor of a more broadly intelligible standard dialect/accent.

When I was doing research on the Gothic Language, an author on Germanic Languages in attempting to explain why generally mutually intelligible Danish, Swedish, & Norwegian were separate languages while almost completely incomparable forms of German were considered dialects gave the definition that: the difference between a language and a dialect is that a language is codified and given an arbitrary "standardized" form by an outside party, usually an academic one. For instance, Danish and Swedish are separate languages because the Dansk Sprognævn and the Svenska Akademien say they are.

English somehow become a rather conservative language (in terms of spelling) even though the closest thing to a governing body are the Oxford & Webster's Dictionaries for the UK & US

Deciding whether Croatian and Serbian are simply dialects of the same language or completely different languages is the kinda hot question that can get you killed.

There's no such thing as "Early Modern English"

Similarly there was no real universal form of Middle English. The form of "Middle English" that most students believe they know of today is because of the widespread teaching of Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales in Anglophone schools. Chaucer's language is really only indicative of a merchant class/lower elite Londoner dialect. If one looks at works from other authors of the "Middle English" age, a very wide spectrum emerges. Writers such as William Langland (from the Midlands), John Gower (from Kent), the "Pearl Poet", the unnamed author of The Pearl & Gawain and the Green Knight (from northern England I believe) show a fantastic variation in the written & spoken dialects of "English" in this age. Political writings from the reigns of Richard II & Henry IV show a further different form of English which was meant for the consumption of the Nobility and Clergy.

Last edited:

From what Owen is saying, any list like that is just a set of arbitrary lines. You would be just as justified in seeing one language or twenty languages. In a case like that, precision is not a virtue.

Gen.Mannerheim

Grand Moff

I am fully aware that the boundaries of language families are also up for dispute and debate, but just because we cannot have an exact answer doesn't mean that an approximate one is impossible. Wikipedia lists: Old Persia, Aramaic, Babylonian, Median, Greek, Elamite and Sumerian. This certainly overlaps with what little I know about Persia, but I feel like this is focussed on the core/urban areas of the empire and doesn't reflect what was going on in Egypt or in the Eurasian steppes. I suspect that sources for the latter will be very hard to find indeed however.

Because the vast majority of spoken dialects have disappeared into the shadows of history without leaving any record behind, its just easy academic shorthand to giver the general "language" without out tripping yourself up with minutia. Its much easier to say "Greek" than trying to sparse out who/where spoke Asian forms of Ionic, Aeolic, or Doric.

This doesn't even begin to touch on the number of creole languages that existed throughout Eurasia. From what I know of a much earlier period, historians have no real way of knowing where use of Sumerian ended and Akkadian began in the fertile crescent, with the most likely answer being that the area was huge creole zone with as many variations as there were towns and villages.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 264

- Replies

- 48

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 2K

- Views

- 152K

- Replies

- 40

- Views

- 4K