1938-1944: Defusing Tensions

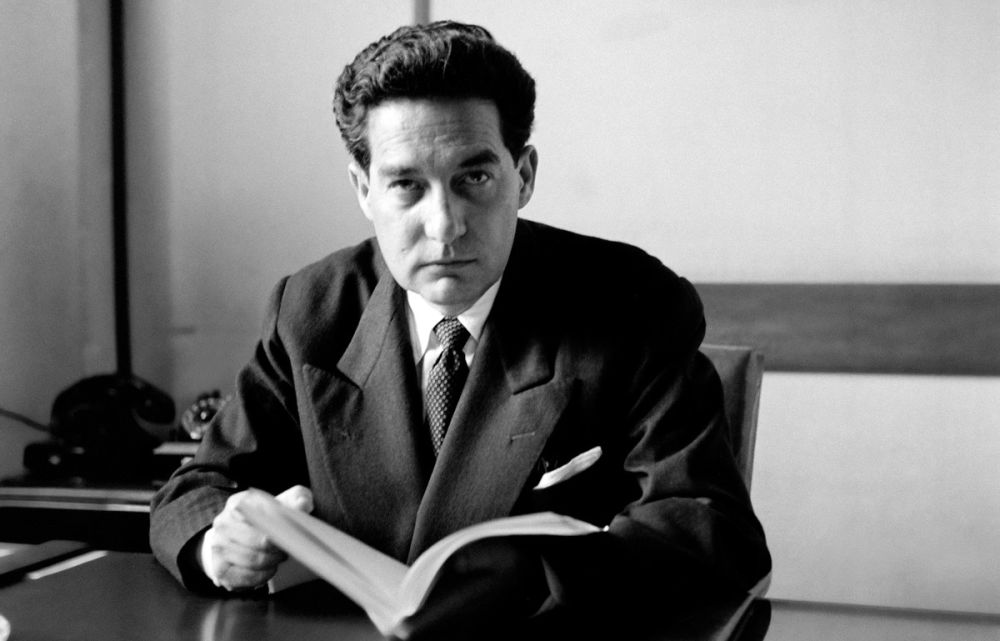

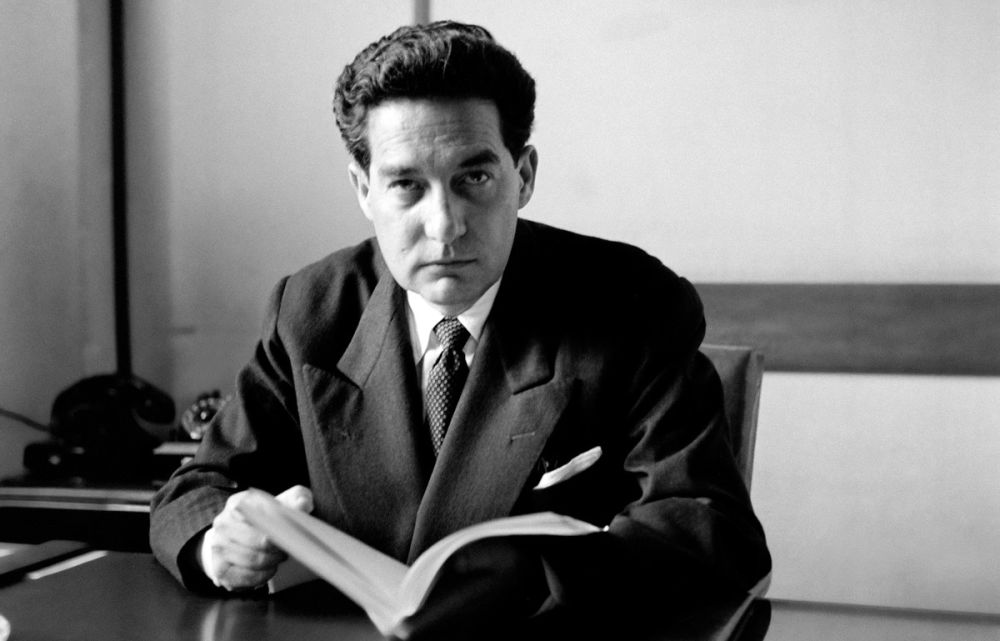

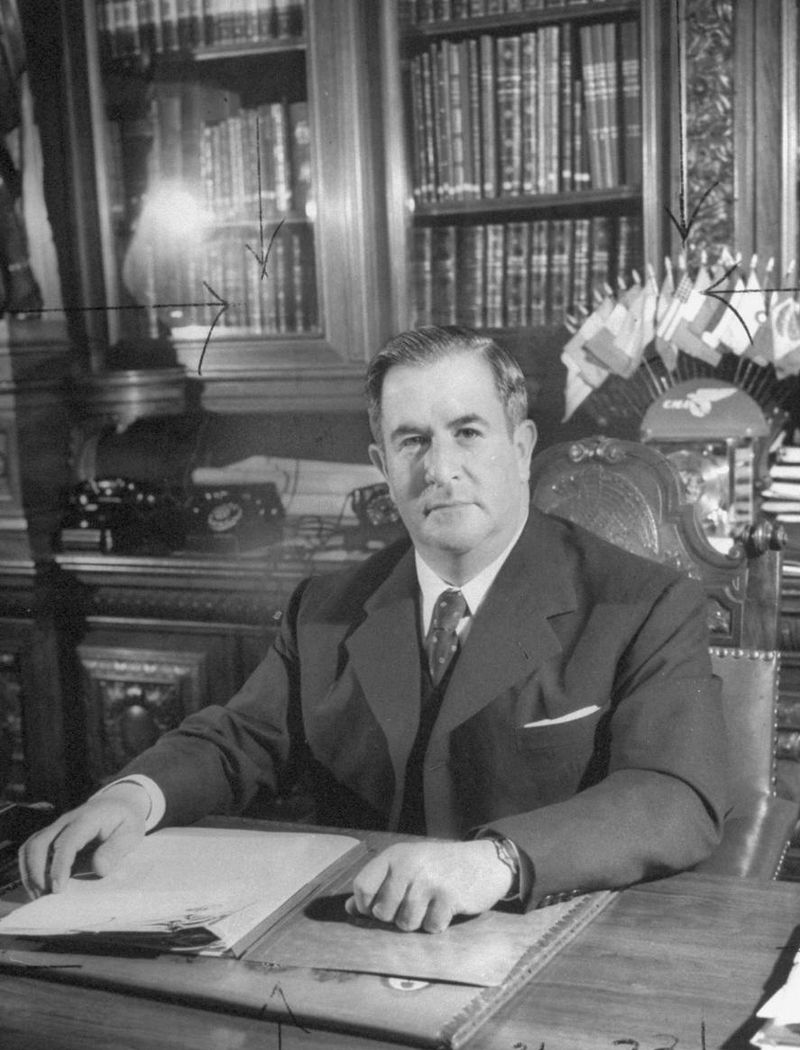

Shortly after securing control of the Presidential office, Horatio Kobayashi began to restore a more traditional status quo. The free market was released from total control, and Mella's plans for assigned careers and prices were scrapped. President Kobayashi did, however, maintain government control over several major industries that he deemed "necessary"; munitions, key manufacturing such as steel and, most importantly, power-plants and electricity. Despite this, he held onto the funds seized by the Communist Party from antiquated landowners. Though largely keeping things under control, even Kobayashi's reasoned approach could not maintain total peace. The remaining militant supporters of Mella and the Communist Party battled constantly against police, soldiers, and other civilians, made only worse by active protests from the right-wing of Mexican politics continuing to spiral. With tensions high, the President declared a State of Emergency, attempting to keep the peace while the government suffered through a near total shutdown.

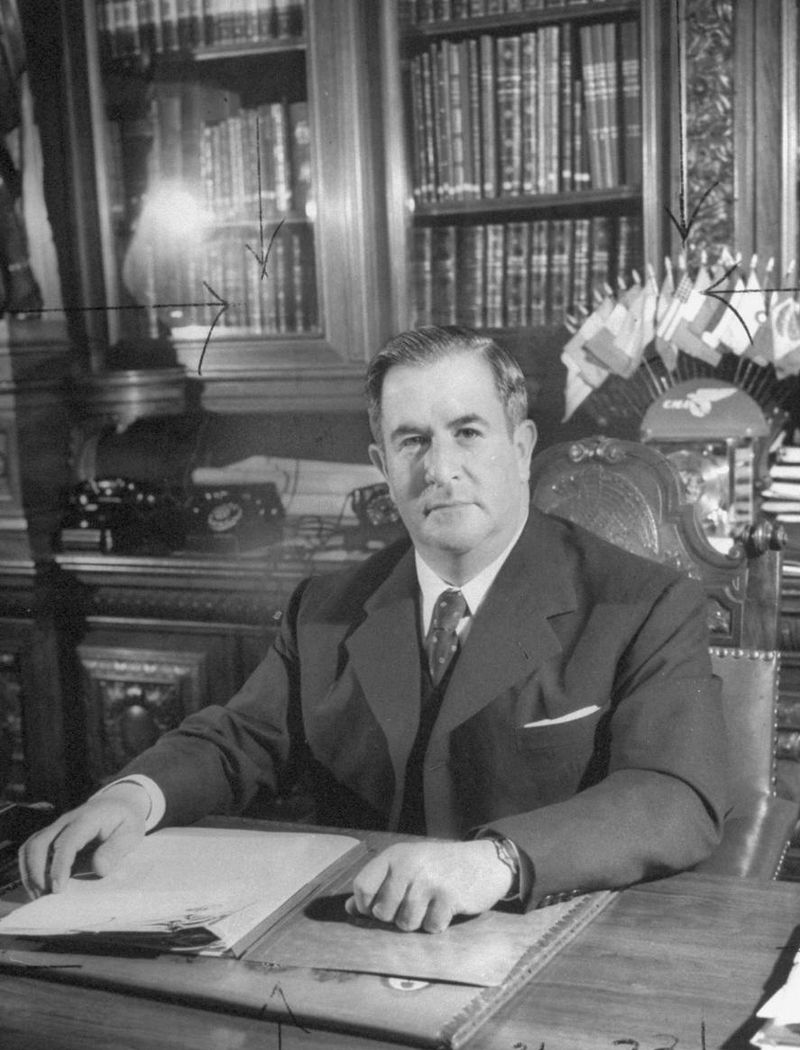

Meanwhile, the Synarchist Union of Dakota still loomed in the north, leaving Kobayashi with a major dilemma. President Elan Vital, if left unchecked, could establish his regime strongly unless dealt with soon. Kobayashi, however, needed Mexican troops to help maintain the peace and lead raids on the most violent Communist rebels, and chose instead to wait for further stability in Mexico before taking action against Vital.

By early 1939, the Russian Empire was finally beginning to buckle under the weight of its own size, made only worse by the Mexican trade embargo. Russian officials had long assumed direct governorship over much of Spain, but were forced to finally secede the entire peninsula to autonomous rule under a satellite government due to the ever rising costs of administration. The Great Bear's age was starting to show.

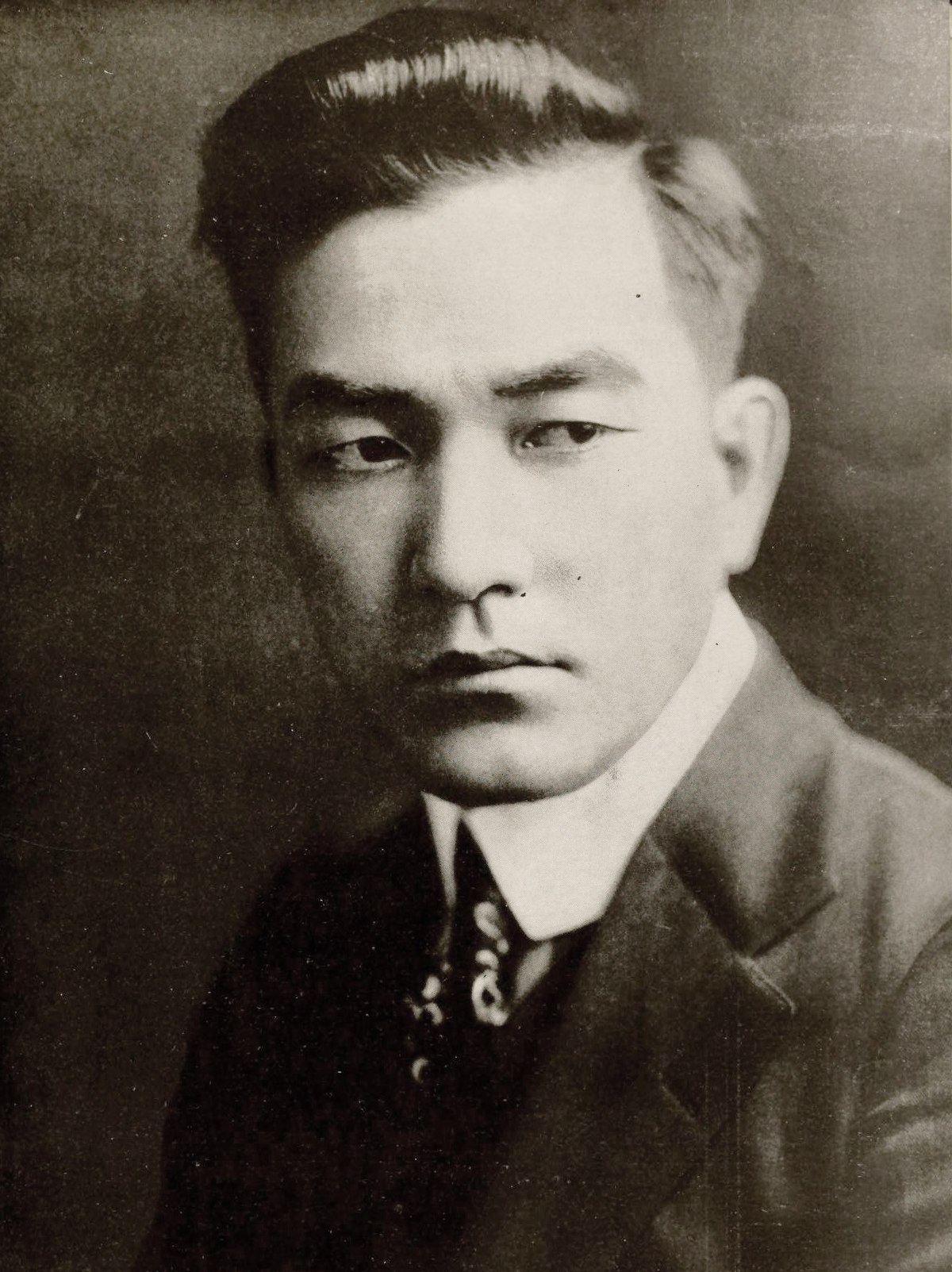

The riots across Mexico lasted for years, but it did not mean President Kobayashi was completely inactive. Though protests were slowly dying down as the army pacified whatever dissidence it could, with most arrests leading to imprisonments rather than executions, as ordered by the President. Additionally, foreign relations were still very much alive, including a newly signed defensive pact with the Republic of China.

By fall of 1940, the tensions had finally subsided. To the surprise of many, no bloody uprising had begun. The cautious use of police and military, accompanied by public exhaustion, had allowed Kobayashi to build up a seemingly stable peace. To continue to show good faith and compromise, the President pushed the "Billy-Club Act" into, law which disarmed Mexican police to match with the largely unarmed civilian population.

With the economy slowly starting to recover, President Kobayashi was once again able to increase the nation's research spending, using the large surplus to even justify running at a temporary deficit. The fastest way to recovery, in the eyes of the Socialist Party, would be for the nation to push for scientific advancement harder than it had in years.

This was followed by an aggressive stance taken towards changing the world and building good faith towards the Mexican Republic. The Mexican government organized various humanitarian missions, led by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Felipe Puerto. Experts were sent to various undeveloped countries to provide medical and scientific knowledge, and democratic movements were also funded or supported. Most of these missions were sent to South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, though a few visited Eastern or Southern Europe as well.

With all affairs in order, the final reunification of Mexico could begin. A non-explicit state of war had existed between Mexico proper and the Dakota Union since the revolution began, and soon the army was preparing to strike at Dakota proper, which lacked the defenses of their affiliated New Orleans.

By late next year, the minor town of Rapidos was once again in Mexican hands. Less than two thousand synarchist soldiers had been defending it, and, when faced by the full might of nearly one hundred thousand professional Mexican soldiers, many fled. The rest of Dakota would likely prove a similarly minor challenge.

Over the next year and a half, the "Dakota March" would prove to be a resounding success. Though the Union infantry would put up a dedicated resistance, they were ultimately no match for the training and numbers of Mexican troops, especially when facing the expert Rurales divisions, and deadly strikes by airships. By 1943, Minneapolis was seized, and President Vital was forced to admit his surrender. He would face charges of treason, but was granted a thirty year sentence instead of death. New Orleans, though uncontested, peacefully returned to the Republic, as its leadership knew their defeat would have been inevitable.

As Kobayashi and his economic advisors had predicted, the new period of peace had allowed the economy to grow further as recovery led to demand. Soon, the national deficit was running as profit once again.

By the end of 1944, a temporary national peace seemed to have been restored. After twelve years of conflict, Mexico City stood once again as a modern metropolis atop the world. Though many Communists still resented the Kobayashi regime, the growing distaste for extremism from the general populace, and a fair crackdown had kept them under control. On a similar vein, most extreme synarchists had been killed or arrested during Dakota's capture, leaving the more peaceful members of the movement leading the way. It seemed, for now, that peace had been restored.

Think of it as them relinquishing total state control of the economy while still spending heavily on social programs and nationalizing. Inherently, socialism and capitalism aren't exclusive... it's just hard to show that with what's available.

Think of it as them relinquishing total state control of the economy while still spending heavily on social programs and nationalizing. Inherently, socialism and capitalism aren't exclusive... it's just hard to show that with what's available.

Think of it as them relinquishing total state control of the economy while still spending heavily on social programs and nationalizing. Inherently, socialism and capitalism aren't exclusive... it's just hard to show that with what's available.

), some peace might be best for Mexico at the moment.

), some peace might be best for Mexico at the moment.