I shall continue where I left off, experiencing the first storm of my life, and describing how I would later venture into space. Now, the alien reader may expect that I had some kind of revenge-agenda, some deep longing to reap justice for my lost love, Namaiaa, that was to drive my actions for evermore. Yet that would be to misunderstand the thought processes of my species. There was no justice, no revenge to be gained. There was only a deep pain and loss to be endured.

I awoke from my first hibernation to find myself on another world, or so it seemed. The landscape of my youth was completely gone. Even the immortal mesas and mountains seemed disfigured. This was a bleak, blank world of mud, dirt, and gravel. The lingering winds still howled against my skin and threw stones in my eyes whenever I dared to open them. Nothing grew, nothing lived, except for small hardy scavengers, picking their way through sheltered piles of debris, hoping to find clumps of decomposing matter.

Yet it is often said that nature loves a blank canvas; and sure enough, I soon saw life renew itself. Many plants of my homeworld have evolved a two-stage lifecycle; some large bulbs survive the storms, but do not themselves grow into viable plants. Instead, they use all their stored energy to burst forth with masses of drifting seeds and spores, using the last of the storm-winds to carpet the newly-tilled topsoil with their offspring and thus gain a headstart on their rivals. Some of these springing-bodies grow to huge sizes, especially after such a long lull between storms. In some places, masses of newly-hatched flying creatures also emerge to feast on the seed-clouds. While wandering out on these renewed plains, I encountered fellow Satellians who had come to admire the short-lived spectacle, or perhaps just to absorb the ambience of the post-storm landscape.

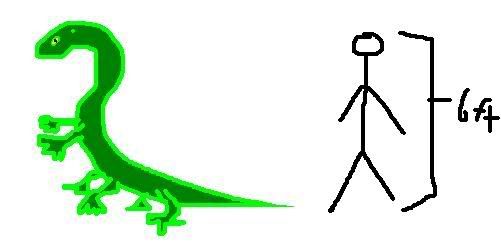

My homeworld has relatively small seas. Most of it is land, and much of this is very fertile; although, since the topsoils are redistributed with every storm, and local weather patterns also have a tendency to change, a jungle may become a desert with the passage of a single storm. Equally, whole lakes and seas can be sucked dry by the immense winds, only for new ones to be deposited by massive floods. Again, I was rather concerned about the fate of my home kin at this time, by which I mean my birth kin; without Namaiaa, I had little interest in keeping touch with my fellow juveniles of Nujunn-Nukk, and I believe that little kinship did not survive the storm; the others, presumably, like me, found their own paths. But I would not actually return home for many years yet; my path changed when I met two Dignitaries from the Aeronautical Kinship of Gurunn-Muurunn-Nannal-Harrur, whom I found temporarily stranded out on the plains along with their crash-landed flying machine. I wasn't able to offer much help, but there was something about our ambient energies in that moment that intrigued the three of us. Now, it was indeed a certain hexapod vehicle from the same Aeronautical Kinship that had killed Namaiaa; again, it may say something about the mentality of our species that I was soon recruited into this same kinship, even before my antennae had regrown.

To lessen the burden of an increasingly-rambling story, I will simply say that I discovered a talent for the art of Gurunnamarue. This word has no direct parallels in any language of which I am aware; it is an artform similar to poetry, with elements of psychological study, as well as highly technical aspects. The practitioner of Gurunnamarue attempts to condense complex ideas and notions into much simpler thought-forms, which are presented as webs of angled text, carrying thought from one place to another, often with no specific ending or starting point. Kinships of the technical arts often rely on Gurunnamarue to communicate their concepts and ideas with the rest of the homeworld. As my involvement grew, I saw the undercities for the first time, and was somewhat underwhelmed - my sense of aesthetics was still tuned to the outside world, and it is hard to grasp the sheer scale of these cities at first - yet I rapidly expanded upon my knowledge of technology; for I was soon invited to tour the offworld facilities of Gurunn-Muurunn-Nannal-Harrur.

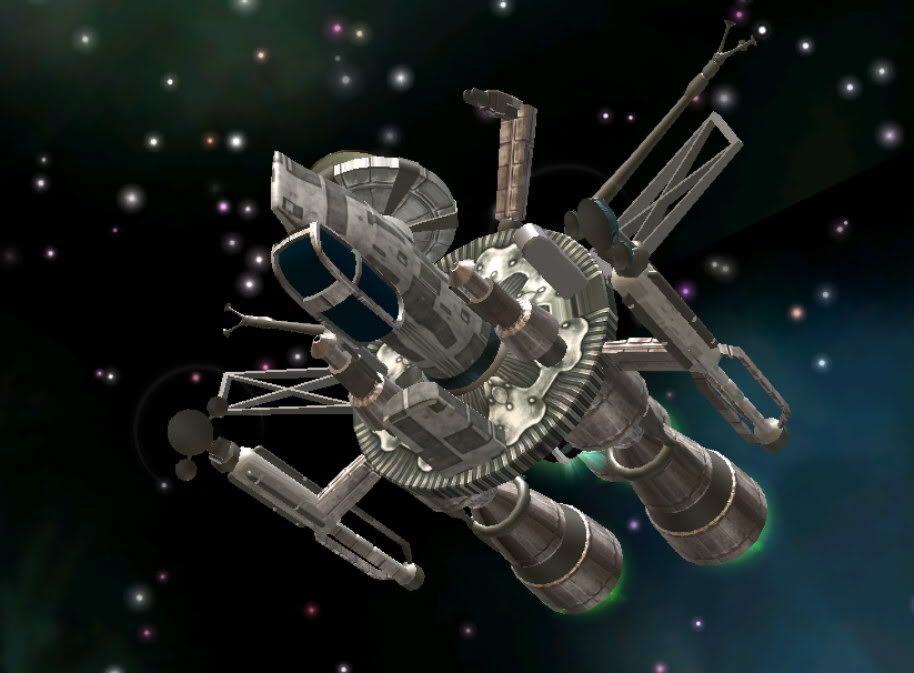

My first blast-off was a day of wonders, a much welcome relief from the previous few days of invasive cleaning and probing by the preparation team; from entering the cavernous launch chamber, to climbing into that sublimely technologent vehicle, to bracing myself against the sudden crushing acceleration - by magnetic impulse tube for the first kilometre, then by radial ramjets, then switching to the barbaric central rocket engine - to viewing my whole homeworld descending beneath me, and seeing a truly black and star-sprinkled sky emerging for the first time... First-timers like myself were easily recognised by our extruded big-eyes, permanently glued to the viewscreens. I then watched as this wondrous darkness was obscured by the growing form of Mennamue, a small dull brown asteroid originally stolen from the outer Sleeper group, now infested by a sprawling space facility like some kind of metallic parasite; here we docked, and had some more time to adjust to the oddities of space - the lack of gravity, the strange sterility, the initially-painful lack of pressure - for reasons of economy and safety, pressure was maintained near the low end of our survivable tolerances - and the sheer ominpresent artificial-ness of our surroundings.

From Mennamue, I eventually ventured to the sister moons beyond; I frolicked naked in the warm toxic seas of Saimue, I jumped and trundled across the dusty voclanic plains of Naiar, and I breathed alien air on the iceworld Maraa. Now, Satellians had been venturing into space for many centuries by this point. But to me, it was all new, and it was all much more than I had dared to anticipate. Suffice to say, that I was deeply inspired by these voyages, and my writings gained ever greater respect. It is here that I must introduce another alien concept to confuse the reader; what we call 'Aihar' may be considered a mix of kudos, respect, sympathy, career level and authority. Aihar is also, in effect, a kind of universal currency, the oldest and longest-lived of all Satellian attempts at introducing such a concept. Now, untimely deaths do not pass without notice amongst my people, especially not the deaths of charismatic young females, and somewhat to my surprise I found that I had gained a head start in my career simply by association with that final, tragic day at Nujunn-Nukk.

I was now forty-five years old, which was still very young for an astronaut, and even younger for a Gurunnamaruist. While awaiting the chance to travel to Hesmue and the outer system, I was to be one of several writers to be invited to the launch of a new kind of space vehicle, one that had been entirely assembled in space itself. As a joint venture between several aero-space kinships, I knew this was something special. But details were deliberately limited, so as not to give us any false expectations which could impact the emotional content of our work. At my insistence, my home kin repaired their centuries-old communication links, so I could send what turned out to be my final farewell; it gave me a mild sense of pride to know they were aware of my works and wished me a safe return.

So we watched from the now-familiar setting of Mennamue, in what could be called an observation lounge, getting mildly intoxicated, gazing at another asteroid-base beyond, waiting patiently for something to happen. To my surprise, and without warning, there was a sudden white flash that blinded my small-eyes - luckily, my big-eyes were closed at that moment - and burnt my outer skin, even through the thickly-shielded windows, which did not survive for a moment longer. Anti-matter is dangerous stuff, indeed. And I can say that vacuum exposure is not pleasant, either, though not necessarily fatal, even for the more vulnerable species; I had been given basic instruction in vacuum survival, and had trained my bodily orifices to resist the pressure gradient. Thus I was picked up by a rescue-drone roughly an hour later, one of several lucky survivors.

Now, if an outside observer, one with sufficiently sensitive instruments, happened to be watching a certain nearby star a few minutes after this event, they might have detected a subtle, short-lived change in the pattern of energy emission, being the only evidence of our first spacetime bubble core completing its interstellar journey and crashing into the heart of another star; this act of cosmic vandalism was hardly intentional, nor was the vaporisation of the rest of the test craft at origin, nor the deaths of dozens of assorted crew, guests, technicians and observers. As I recuperated inside a rescue shuttle-craft, the talk was already of what to do next; perhaps annihilation-reaction should be abandoned in favour of super electron-dense materials as a power source? I couldn't have known, but at that exact time my home kin were dying sudden and terrible deaths, as the debris from Mennamue station and other assorted orbitals crashed down upon the surface of Hmmaiaa, resulting in several secondary anti-matter explosions and the obliteration of approximately one-tenth of the homeworld's surface.

As soon as I was able, I returned to my home kinship of Hammul Ulurr-Nunn, or at least to the coordinates I was given. I recognised nothing; there was perhaps just a faint rise in the blacked rock where our home plateau had been. Even those who were veterans of many storms said they had seen nothing like this before. My Aihar was once again raised by tragedy, but I desired no part in the ensuing discussions; I didn't care about new safety protocols, and I didn't care about what direction our technological efforts should take. We Satellians pride ourselves on being unsentimental, but I could not help feeling a great sense of numbness at this time. Everything seemed wrong; I simply wanted to sleep, for a long time, until things changed for the better. So I used up some of my Aihar-credit on a visit to a biotician kinship, taking various drugs and having various implants inserted into my body to prepare it for an unnaturally-long hibernation. I called the few friends I had left in order to say farewell, and then I searched the scorched expanses of my homeland for days, until I found a suitably sheltered cave. My last act was to glue myself to the ceiling - just in case of flooding - and then I cast my mind over my bodily functions, putting them to sleep one by one.

It is said that the urge to explore and expand is too strong for any species to resist. Individuals have long memories, but tragedies rarely register for long on the scale of multitudes. Lessons are learned, promises are made, and things move forward again. While I slept, the aftermath of these events was spurring the rise of Hmmurue, The Agreement, forging the aero-space kingships together, laying out standard procedures and safety protocols; anti-matter research was moved all the way out to the Jewel Ring, and eventually, more superlight experiments were carried out, some using safer but much more limited power sources. To start with, there were short hops to the edge of the system and back; it was not until I had been asleep for twenty-five years that the first Satellians ventured to a nearby star and returned in one piece. Storms came and went on Hmmaiaa, depositing new sediments over irradiated ground and allowing life to bloom once more. There followed another thirty years of slow but exciting developments... After so many false starts over hundreds - thousands - of years, Satellian science and industry were finally moving with real purpose. Or so it seemed.

I fear I have written far too much now; at this point my life is only just beginning, but this segment of my story can now be considered complete. So again, I will leave the reader with my goodwill and gratitude.