Bibor

Doomsday Machine

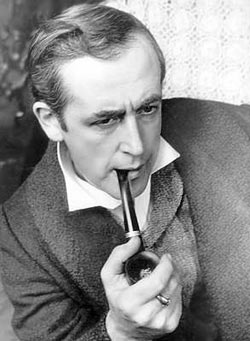

I've read almost all Sherlock books when I was young. In fact, I returned to these books at least once.

What irks me most about screen adaptations of Sherlock Holmes is that they completely misrepresent why he was successful as a detective. They usually portray him as a genius, almost at the level of a savant or mystic seer, often also as an arrogant individual, fully willing to display his alleged intellectual superiority. That's Hercul Poirot, not Sherlock Holmes.

There are in fact three key components to Sherlock's success, all equally represented in the books, and all three fit perfectly with even the most advanced conteporary detective / espionage methods we see today:

1. Using reasoning based on evidence to reach conclusions. This needs to be put into context: this was *not* the norm in Victorian England, but was becoming popular.

2. Dedication to his vocation. He trained, acquired knowledge and proactively sought out whatever he needed to succeed in his task. Even if it meant sacrificing everything else: friendships, private life, health etc. Also, in the books, this was not portrayed as a virtue. He was often criticized and he often self-criticized about this, because sometimes it was effective for the one thing he needed, but proved detrimental for the case as a whole. As with reasoning and evidence, this trait is rare even today, let alone in the Victorian era, when the dominant social structure was based on class. "It doesn't matter who you are, but how capable you are."

3. His extreme sensibility to social context. This is perhaps the thing that most adaptations completely miss. Victorian England was a two-class system: the upper and the lower class. In the books, it's very clearly defined that his demeanor is constantly shifting so that you can never tell to which class he belongs, and he was dipping into both worlds when needed. His use of the lower class: servants, stable boys, beggars, valets, thieves. He had an extensive network of informants the upper class would treat as invisible, unseen people. He infiltrated both the lower and upper class, often using props and disguise . In the modern world, one could say he was a hacker. The way he was able to gather information and infiltrate locations was the reason why he was so successful when cases were in London and why it was such a hit-and-miss when outside of London (for example, Hound of the Baskervilles, playing out in the countryside, strains his other abilities, since he has no network of informants to rely on). It's also very important to say that the exaggeration of his intellectual abilities was in large part to hide and protect his information network. He might claim "I just deduced it!" and give a semi-believeable explanation, when in fact he meticulously gathered real information elsewhere.

Af all the adaptations, I'm afraid to say Elementary by CBS is the one I consider closest to the general idea of who Sherlock Holmes is and what these stories are about. Even if I don't always agree with the screenwriters, at least I can confidently say they read and truly understood the source material.

What irks me most about screen adaptations of Sherlock Holmes is that they completely misrepresent why he was successful as a detective. They usually portray him as a genius, almost at the level of a savant or mystic seer, often also as an arrogant individual, fully willing to display his alleged intellectual superiority. That's Hercul Poirot, not Sherlock Holmes.

There are in fact three key components to Sherlock's success, all equally represented in the books, and all three fit perfectly with even the most advanced conteporary detective / espionage methods we see today:

1. Using reasoning based on evidence to reach conclusions. This needs to be put into context: this was *not* the norm in Victorian England, but was becoming popular.

2. Dedication to his vocation. He trained, acquired knowledge and proactively sought out whatever he needed to succeed in his task. Even if it meant sacrificing everything else: friendships, private life, health etc. Also, in the books, this was not portrayed as a virtue. He was often criticized and he often self-criticized about this, because sometimes it was effective for the one thing he needed, but proved detrimental for the case as a whole. As with reasoning and evidence, this trait is rare even today, let alone in the Victorian era, when the dominant social structure was based on class. "It doesn't matter who you are, but how capable you are."

3. His extreme sensibility to social context. This is perhaps the thing that most adaptations completely miss. Victorian England was a two-class system: the upper and the lower class. In the books, it's very clearly defined that his demeanor is constantly shifting so that you can never tell to which class he belongs, and he was dipping into both worlds when needed. His use of the lower class: servants, stable boys, beggars, valets, thieves. He had an extensive network of informants the upper class would treat as invisible, unseen people. He infiltrated both the lower and upper class, often using props and disguise . In the modern world, one could say he was a hacker. The way he was able to gather information and infiltrate locations was the reason why he was so successful when cases were in London and why it was such a hit-and-miss when outside of London (for example, Hound of the Baskervilles, playing out in the countryside, strains his other abilities, since he has no network of informants to rely on). It's also very important to say that the exaggeration of his intellectual abilities was in large part to hide and protect his information network. He might claim "I just deduced it!" and give a semi-believeable explanation, when in fact he meticulously gathered real information elsewhere.

Af all the adaptations, I'm afraid to say Elementary by CBS is the one I consider closest to the general idea of who Sherlock Holmes is and what these stories are about. Even if I don't always agree with the screenwriters, at least I can confidently say they read and truly understood the source material.