Thorgalaeg

Deity

So better than the Hubble?

Your comment made me think on it and I've come to the conclusion that it's both an overblown problem and also not really a problem to begin with.As for the assignment, a few pages back, Winner lamented our society's appetite for science fiction eye candy rather than real world current space endeavors. I brought up that it was because of our society's instant gratification culture. Perhaps you could bring something up about combating that?

While I touched on this topic tangentially, I can't really go into it in-depth and I don't really need to do so to make my point.

While I touched on this topic tangentially, I can't really go into it in-depth and I don't really need to do so to make my point. I've had him in other classes (and am stuck with him in all of my classes for the next 2 years) and he's uncouth to say the least. He has point blank told professors they are wrong during lecture - not by showing defference of any kind for the professor and gently broaching the inaccuracy, perceive or otherwise. Instead, he just shouts 'YOUR WRONG' during the middle of lecture.

I've had him in other classes (and am stuck with him in all of my classes for the next 2 years) and he's uncouth to say the least. He has point blank told professors they are wrong during lecture - not by showing defference of any kind for the professor and gently broaching the inaccuracy, perceive or otherwise. Instead, he just shouts 'YOUR WRONG' during the middle of lecture. To address the criticism upfront, I do need to go back in and make more explicit references to the programs I'm talking about. This paper was intended to answer a question about one specific program (the asteroid mission) so I wrote it in light of that. My point was that Obama should double-down on that and increase funding and schedule more launches to support that mission instead of changing course drastically. So in essence, I'm advocating that Obama should focus the nations attention on this one program and use it as the focal point of NASA in general, much like Apollo or Shuttle programs were focal points even though other missions were going on concurrently. However, to be a good paper it needs to be readable by a more general audience than one professor, so I will definitely clear things up and I appreciate the advice.You propose to expand NASA's current plans, but in my opinion you stay to vague on where that expansion is supposed to be headed. If you want to excite the public, you need a vision where NASA is headed, something that the people can get behind. If you want NASA's agenda at the forefront of public society, there needs to be a clear NASA agenda first (which is of course difficult to formulate when politicians meddle with NASA all the time).

You can rely on Obama giving rousing speeches, but you have to give him a little more to work with than (forgive me the oversimplification): "We need to do space stuff,because...space!!!" I would add a short description in which direction NASA should be heading in the near future. What do you want to achieve?

Unfortunately, right now it is too late in the night for me to think about what my vision would be.

See above. While I could have (and will) written this to make more explicit references to what I was talking about as far as goals and programs, it was implicit in that I was answering a specific question about a specific program. I suggest that Obama should make that program (the asteroid mission) the main purpose of the program in that it's the biggest and most difficult mission objective they face. I'm not downgrading the rest of their efforts, rather I think that the SLS/asteroid project should be the centerpiece (as it de facto already is) of NASA's reason to exist and Obama should try and raise awareness of that and advocate for increased funding for it.Well, my comments in brief:

1) First and foremost, identify what the purpose of the space programme is. Until that has been boiled down to a few clear points that can be sold to the public through a political process, all other discussion is rather moot. This could be seen as a "strategic" level of analysis, i.e. what is the overall objective. Why we are doing this. What is the benefit? How will this help us in the long term? And are any of these claims firmly based in reality, or have we just conjured them up to keep our jobs safe? Forgive for using the military analogy, but I can think of no better way to express what I mean:

Yes! All this, exactly! What I'm saying is that now NASA needs concrete focus on this major objective, capturing an asteroid. Changing the objectives of the Constellation/SLS program yet again would be a disaster and would cause only more setbacks and overruns. So what I'm saying is that it's time to stop being vague about 'flexible paths' and only half-heartedly funding that path. It's time he set concrete goals, on the order of a decade in timescale, with a firm path to get to those goals. I'm not saying the asteroid mission is the best technical mission to accomplish, I'm saying it's the one that the agency has been working toward and at this point it's the only one they can hope to realistically accomplish in a decent timeframe. Going to the moon and especially setting up a moon base will require major readjustments to the mission architecture and in light of all the other major recent changes, it just isn't feasible to do IMO in the near future. Further, as I stated in the paper, the attempts to make NASA do a moon mission legislatively are completely fiscally impossible. It's not like Congress has authorized and funded their moon plans - rather, they are placing demands on NASA and giving absolutely no funding to do it and this is largely for political gain against Obama.Back to the (human spaceflight part of) space programme - like the German military, it's constantly being redirected to wildly different goals, which in the end assures that nothing at all is accomplished. Fromcapturing Moscowreturning to the Moon toseizing the Caucasusgoing to an asteroid tooccupying Stalingradgoing to Mars. No doubt, ifwinter clothingfunds had been provided along with a firm strategic direction, NASA would have already beenin Moscowback on the Moon, perhaps building a base and learning how to produceoil for the Reich warmachinepropellant for transport to low-Earth orbit. By changing the strategic directionof the invasion of the USSRaway from the Moon,HitlerObama ensured that the program would be completely derailed, with a decade of planning and a stable bipartisan support of that goal squandered in a stroke of a pen. Even worse, he didn't even replace it with another overall strategic plan of his own, just a nebulous "we might do this and that" joke-of-a-plan called the "flexible path"(back to Berlin).

The objective of what to do and why is already settled from my perspective - we're going to capture and asteroid and we should do it for the reasons laid out in my paper (the economic, political and technological gains to be had from an asteroid mission and the commercial ventures). The tactics of how to do it are already largely settled. Now looking at the moon proposal or other various missions, those don't have much of a justification of why to do it. Though I could do that myself, I chose not to because I feel that we're already committed and shouldn't change it up yet again. Also, political considerations weigh very heavily against the moon proposal. It was essentially another tool that the Republicans have used to get at Obama. Not only could they force him to concede the asteroid mission to them, but he would also have to make other major concessions to fund the moon mission such as de-funding Obamacare. I can't emphasize how central that is to the Republican plan, the asteroid mission is already funded (though at suboptimal levels), the Republican plan isn't and will only be funded if Obama agrees to massive cuts elsewhere.2) Only when you identify what you want to do and why, you choose the method of accomplishing the goal. This is the "tactical" level of analysis. I separate the two because they often get mixed up; people endlessly argue about how to do this and that in space, that they forget about why they want to do that in the first place. Whether you go back to the Moon in a two-stage chemical lander or a you lower yourself on a kevlar string from L2 is irrelevant from the strategic point of view.

I think that would be a disaster to be honest. Not because they are above firing and infallible, rather because in the current climate it will be extremely difficult for Obama to appoint another administrator and will involve yet more political fighting and horse-trading at a moment where that's the last thing NASA can afford. You would be facing a NASA without leadership potentially for years if you did that and the last time it happened (after Obama was elected) you winded up with the Constellation program being cancelled, then partially resurrected, and yet more delays. It's also important not to send a scare that could negatively impact NASA other employees. With the sequester, everyone's job is already at stake and the last thing you want is to send a message is that everyone is expendable even more so than the current political machinations would imply.1) Fire Bolden and all the people he brought to NASA, put all current plans on hold, and start with a clean sheet.

They already did that and the result was the plan to go to an asteroid (though capturing the asteroid was a later development). The problem is that you aren't going to get consensus because the various advocacy groups already have their own objectives (which can and often do run contrary to NASA objectives) and everyone who cares about space has their own personal priorities. I just don't see the point in repeating the work of the last panel, to be honest.2) Assemble a panel of leading spaceflight experts, representatives of the relevant committees of Congress from both parties, heads of relevant NASA centres, space entrepreneurs, representatives of space advocacy groups, leaders of other space agencies (ESA, the Russians, Indians, Japanese, even the Chinese), scientists, futurists, economists, and other relevant people, and have them formulate several STRATEGIC approaches for human spaceflight in the coming decades. These might include the well-known Moon first versus Mars first options, the "screw planets, Asteroids!" option, and others.

I completely agree with everything but the kill-switch. This is NASA dude, and if there were such kill-switches in place, nothing would get done.3) Evaluate the proposed options in terms of affordability, pay-offs, impact on the economy and education, and the potential for international cooperation. The best option would be adopted and translated into a binding mandate, hopefully enjoying bipartisan support. A "kill-switch" would be incorporated ensuring that if major changes are made to the programme that would derail it from its strategic objective, the programme would automatically be cancelled.

It's not like our government doesn't already do this in practice for various reasons; look at the Apollo program, or the DC-X to name but two.

It's not like our government doesn't already do this in practice for various reasons; look at the Apollo program, or the DC-X to name but two.[/QUOTE]4) Market the plan. Explain it to the public - why we are doing it, why is it worth your tax money, how will this benefit the nation and mankind at large in the future.

5) Stick to it.

A bit of American space alarmism, for entertainment purposes:

). However, it's part of our national psyche and it isn't altogether a bad thing because it does push us to move, even if by moving we're only reacting. Because if there's one thing we do excel at, it's overreacting. We didn't have to set the lunar landing as a response to USSR's space achievements, it was a bit of overkill. But we did and look what it got us. Similarly, we didn't have even have to create a massive civilian department like NASA to counter the Russians either, the military had it's own space programs that could have been furthered. But we did create NASA in response to Sputnik and it did lead to Apollo and it didn't end with Apollo either. The downside is that naturally, we do tend to lose focus when we've won - we did cancel 3 planned lunar landings after all.

). However, it's part of our national psyche and it isn't altogether a bad thing because it does push us to move, even if by moving we're only reacting. Because if there's one thing we do excel at, it's overreacting. We didn't have to set the lunar landing as a response to USSR's space achievements, it was a bit of overkill. But we did and look what it got us. Similarly, we didn't have even have to create a massive civilian department like NASA to counter the Russians either, the military had it's own space programs that could have been furthered. But we did create NASA in response to Sputnik and it did lead to Apollo and it didn't end with Apollo either. The downside is that naturally, we do tend to lose focus when we've won - we did cancel 3 planned lunar landings after all.

Well, I don't want to quote-ize the post, so I'll just respond with a couple of points

1) I respectfully disagree with you on the asteroid capture plan. I just don't see it working from the strategic point of view, i.e. in terms of a) WHY are we doing it and b) HOW will this help the space programme in the long term. To me it really seems as a dead end - and by that I do not mean it would be a total waste of time and effort (as, for example, using the money for building a pyramid would be), just that it doesn't leave much in terms of capability. The mission ends, and then what?

2) The asteroid mission plan isn't a strategic goal. It is at best an operational goal. I have to ask - what is the US strategy in space? Can anybody really answer that at this point? I doubt it. And therefore, is it really all that smart to commit to a particular mission until you have your strategy figured out? I think the major reason for the US human spaceflight malaise today is that nobody has succeeded in establishing a credible strategy for it. In the absence of an overall strategy, administration after administration, beginning with Nixon, has focused on intermediary, ad hoc goals, hoping that somehow, sometime, things will just fit together and then it would be possible to claim that there was a strategy driving all these efforts all along. Well, that didn't work. In the absence of a strategy, these steps are taken in different directions and so in the end, the programme is just drifting, aimlessly, wasting enormous amounts of money in the process. That ought to cause backlash.

3) So, instead of planning for a mission, we should really just take a break and figure out a strategy. And by that I mean LONG TERM strategy, not a Zubrin's 10-year tactical plan. What do we want to achieve in 50 years? What's our vision? This needs to be formed around a consensus that is maintainable. This is where the Augustine committee failed miserably, and it chose to call the failure a "flexible path". Well, I am sorry, but the lack of a strategy isn't strategy. Obama should have told them "WTH is this crap? Start over and don't come back until you have a 10-page plain language document outlining a multi-decadal, affordable space strategy which is consensual enough for me to be able to sell it."

---

This is a challenge to all people here in this thread, by the way. Try to tell me what is the point of a space programme (any space programme, let's not limit ourselves to NASA). What should be our long term strategy with regard to human spaceflight?

So better than the Hubble?

Hopefully this paper will urge Congress towards adopting these measures and ensuring USA #1 forever.

To address the points in order:Well, I don't want to quote-ize the post, so I'll just respond with a couple of points

1) I respectfully disagree with you on the asteroid capture plan. I just don't see it working from the strategic point of view, i.e. in terms of a) WHY are we doing it and b) HOW will this help the space programme in the long term. To me it really seems as a dead end - and by that I do not mean it would be a total waste of time and effort (as, for example, using the money for building a pyramid would be), just that it doesn't leave much in terms of capability. The mission ends, and then what?

2) The asteroid mission plan isn't a strategic goal. It is at best an operational goal. I have to ask - what is the US strategy in space? Can anybody really answer that at this point? I doubt it. And therefore, is it really all that smart to commit to a particular mission until you have your strategy figured out? I think the major reason for the US human spaceflight malaise today is that nobody has succeeded in establishing a credible strategy for it. In the absence of an overall strategy, administration after administration, beginning with Nixon, has focused on intermediary, ad hoc goals, hoping that somehow, sometime, things will just fit together and then it would be possible to claim that there was a strategy driving all these efforts all along. Well, that didn't work. In the absence of a strategy, these steps are taken in different directions and so in the end, the programme is just drifting, aimlessly, wasting enormous amounts of money in the process. That ought to cause backlash.

3) So, instead of planning for a mission, we should really just take a break and figure out a strategy. And by that I mean LONG TERM strategy, not a Zubrin's 10-year tactical plan. What do we want to achieve in 50 years? What's our vision? This needs to be formed around a consensus that is maintainable. This is where the Augustine committee failed miserably, and it chose to call the failure a "flexible path". Well, I am sorry, but the lack of a strategy isn't strategy. Obama should have told them "WTH is this crap? Start over and don't come back until you have a 10-page plain language document outlining a multi-decadal, affordable space strategy which is consensual enough for me to be able to sell it."

---

This is a challenge to all people here in this thread, by the way. Try to tell me what is the point of a space programme (any space programme, let's not limit ourselves to NASA). What should be our long term strategy with regard to human spaceflight?

The ultimate US goal in space at the moment is to learn about space and to invent the methods and technologies to push the boundaries and rise to the challenges presented by space and the asteroid mission would do just that and is therefore a strategic goal in and of itself. I'll come back to this point in a later answer.

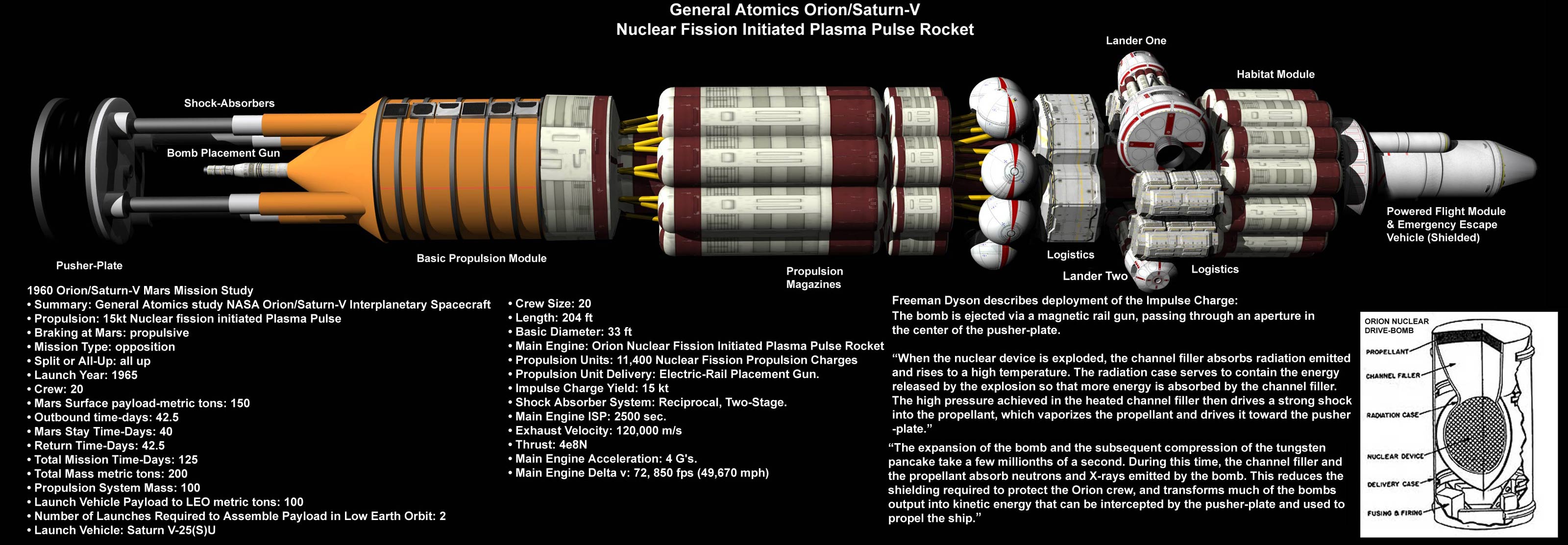

The ultimate US goal in space at the moment is to learn about space and to invent the methods and technologies to push the boundaries and rise to the challenges presented by space and the asteroid mission would do just that and is therefore a strategic goal in and of itself. I'll come back to this point in a later answer.I know, it's nuts! It's one of my favorite 'could have been' programs. BTW, on youtube they have clips of test launches they did to verify the overall approach. They built a scale model of the Orion ship and exploded a series of high explosive charges under it to send it up into the air. It's pretty coolJust seen a documentary about the Project Orion. I've read about it before, but I am simply fascinated by the odd mix of plausibility and utter insanity than it combines in one package

[/SPOILER]

BTW, I was inspired by KSP and PlutonianEmpire's post a few weeks back to think about a hypothetical scenario of Earth having two moons.

In addition to our normal Moon, we also have a much smaller one, say ~1500 km diameter, orbiting near the edge of Earth's Hill's sphere, say, about 900,000 km. This 2nd moon is locked in an orbital resonance with our primary Moon. However, its inclination and appearance suggests it is a foreign body, possibly captured by the Earth during the Late Heavy Bombardment period about 4 billion years ago.

From the Earth, the 2nd moon appears pretty small, about 1/5th the Moon's apparent size in the sky.

Assuming it doesn't butterfly away humanity (as it probably would) and there was a space race as in our timeline's 1960s, which of the two moons would we visit first?

).

).Flying to a further out asteroid isn't going to give us any new propulsive techniques either with the current state of technology. We'd still be using a chemical rocket system to do a longer-range mission to a bigger asteroid. Actually, we'd learn quite a bit less from going to a further away, bigger asteroid than the current mission. The act of capturing and moving an asteroid - even a small(er) one is a major feat itself and will require fine tuning a lot of techniques, it's not like it's a perfectly symmetrical payload itself and moving it in this manner is a novel thing to do that we can learn from. Simply going to an asteroid and returning is not itself a new technique.I'll be brief about my comments concerning the proposed asteroid capture mission (henceforward referred to as ASCAP - let's use an acronym to sound more NASA-ish).

1) I agree with your reasons, but I don't see how they apply to ASCAP. This was discussed with the articles we posted in this thread before, but to recap - travelling to a boulder-size rock in cislunar space is not a proper mission to do any of the things you mentioned. Navigation/propulsion-wise, it's similar to sending an Orion to loiter for a while in L2 or low lunar orbit. Nothing new is learned there. The rock itself is far too small to provide any serious experience with landing on proper asteroids, which are kilometres in size. Bagging the rock and capturing likewise doesn't give us anything that would directly apply to deflection of proper asteroids. It's a stunt, not a part of any credible strategy for dealing with threatening asteroids. Concerning science - as mentioned by Spudis, Orion is not equipped for any in-depth study of the rock, and even less for experimenting with ISRU. The most the astronauts could do would be to chip off a few pieces and carry them back to Earth. Well, that can be done robotically with a much smaller probe/launch vehicle, so no need to waste one super-expensive SLS for such mission. Even if ASCAP goes ahead and the micro-asteroid is indeed bagged, captured, and put in an orbit around the Earth (or the Moon, whatever), give me one unquestionable benefit of sending humans to it in an Orion/SLS ($2-8 billion overall cost) instead of a simple robotic sample return mission which can be developed/launched for a small fraction of the cost.

And what's more ambitious than capturing an asteroid, moving its orbit and going out and studying it? There's no possibility of a Mars mission in this timeframe and with the problems I previously raised about funding, a moon mission is out as well. I'm getting the feeling that a lot of the blowback against the ASCAP mission is simply because it isn't anything that people who've already made up their minds about NASA's future want to do. What I mean is that it doesn't satisfy the Mars Nuts or the Moon Nuts, so they wind up doing weird mental gymnastics (like Spudis's attack on the science capability of the mission) to discredit it - even when a cursory analysis shows they're way off and highly unrealistic.2) As I see it, the ASCAP mission is an excuse not to do attempt something more worthwhile and ambitious. If the only purpose of ASCAP is to provide some rationale for the SLS (currently a rocket without a mission) while fitting in the limited budget, then that is again symptomatic of the lack of overall strategy in the US space programme.

Please explain how this makes sense and how the SLS isn't being put 'to good use' under the current ASCAP plan.3) At the very least, ASCAP should be changed into ASREC - Asteroid Reconnaissance mission, which would include people being sent BEYOND cislunar space to visit one of the larger NEOs in heliocentric orbit. That way, something new about human spaceflight would be learned and the SLS would be put to a good use. The costs should not be that much higher, and if it takes a few more years to prepare for it, so be it.

That's not a fair comparison at all because attacking the USSR is most decidedly not a justified exercise of state resources. Building up our capabilities in outer space from a commercial, economic, technological and political standpoint(s) are. We're building up our technology to go into deep space, we're working with international partners to do so (The ESA is building the Orion service module), we're developing new technologies as well. So all that is actually covered in the current flexible path. The flexible path is a strategy and I've said why, your rebuttal here rests on this flawed analysis from my perspective. How is it not a strategy? It's a strategy without a concrete, singular goal, for sure, but I've already talked about how doing that is not a guarantor of long-term success (see Apollo shut-down).Now for the strategy - the "flexible path" is not a strategy. Sticking with the German military analogy, it would translate into "let's develop all kinds of fancy weapons our guys dream up, with the ultimate goal of attacking the USSR sometime in late 1970s".

How does the flexible path fail to provide this?A credible strategy must include an objective, a set of concrete steps and/or procedures to achieve it, and an analysis of resources needed to pursue it.

I've been specifically playing with a few story ideas. One, say we find a 500 km Kuiper belt object heading toward a collision with Earth in 12 years. The impact of a body so big would eradicate all life on Earth, evaporate all oceans, melt the salt in the empty ocean basins, and heat bedrock in depths measured in kilometres. Nothing except perhaps a few bacteria living very deep underground would survive.

Link to video.

Reread my last post.I still don't see how bagging a boulder and changing its orbit is significant. How does it help? What does it prove? Are we going to need to bag boulders for our return to the Moon, or on our way to Mars? And I am *not* being flippant here, I just don't get it.

And a trip out to the moon doesn't do that? A long (time wise) trip out there can test all of those things with the possible exception of navigation, but even that's debatable.Visiting a larger asteroid in heliocentric orbit on a proper long-duration mission offers several advantages. One, it is a dress rehearsal for the trip to Mars in terms of transit times, navigation, communication, life support, etc. In fact, it would be quite similar in principle to a trip to the Moons of Mars, only shorter. (Meaning we could easily skip it and go for Phobos or Deimos straight away).

---> Implying smaller asteroids can't be rubble piles or even big in their own right.I disagree with the notion that it doesn't matter if we capture a few metres sized boulder or visit and study a 5 km asteroid. The former is likely going to be a piece of a bigger asteroid in the first place (as you said), but more importantly, we know little of the structure of the bigger rocks. Ideally, we should learn how "rubble piles" and other types of asteroids behave, try to drill deep into them, practice touching down on their surface (which might be difficult due to their rotation), find out if perhaps they don't contain water ice below the surface, these sort of things. It will also look better if you can put a flag on something that isn't of the same size as the flag itself.

You say these things but don't justify them nor refute what I already said on it.The payoff in visiting a suitably large asteroid in its natural environment, instead of playing around with a tiny captured one, is bigger both in scientific and spaceflight experience terms, and it will also be easier to sell as 'exploration'.

And why is going to a small asteroid less useful? You've yet to address the issues I raised in the benefits of going to a smaller one versus going to a large one.At this point I'd like to stress that I don't think visiting asteroids of any kind is a vital next step for human spaceflight and that it should have priority over other kinds of things we can do in space. I am just pretty convinced now that IF we want to do something that makes sense and IF we must go to an asteroid, we might just as well go for something that's challenging and useful in terms of future exploration missions, as well as training in case we needed to deflect a large asteroid heading for Earth. The cost-benefit ratio is more favourable, in my opinion.

As for my question, I think it is relevant. I do not see WHY do we even need humans on the ASCAP. It seems NASA could accomplish everything that is of any technical/science value by unmanned automated or even teleoperated spacecraft (it'll be close enough to Earth for that) at a (much) lower cost.

Sheesh, I really did not want to get bogged down in this. To me, it's besides the point. If ASCAP was a part of a clearly defined strategic approach to human spaceflight, I would shut up at once. But in the absence of such strategy, we might just as well spend the money on bigger space telescopes or a robotic Mars sample return mission or any number of unmanned missions which could make a better use of SLS's heavy lift capability. In fact, it'd be better to kill beyond LEO human spaceflight dreams altogether because trying to do it without a strategy is just a waste of time and money.

"Flexible path" is not a strategy precisely because it does not present any kind of a goal or a direction. Apollo programme was based on a strategy. VSE was a strategy. Flexible path could be summed up as "we don't know where we want to go, how, when, what we want to do there, or whether we'll have money for it." You want to call that a strategy? A proper strategy would identify a goal or goals, justify them, offer a provisional timetable for achieving them, and set aside the necessary resources.

A main advantage of having a strategy is that you can measure the merit of a particular mission proposal (such as ASCAP) in terms of its usefulness for achieving the goals of the strategy. Not having a strategy means you don't know whether the proposed mission is useful or not; there is no baseline against which you can evaluate it.

I believe that's the problem here.

What's super-duper cool is that it will be able to communicate with Curiosity and they will be able to tag-team their scientific study of the atmosphere.

What's super-duper cool is that it will be able to communicate with Curiosity and they will be able to tag-team their scientific study of the atmosphere.

Well, I don't think novae are quite that short, especially considering we just had one just last month (Nova Delphinae 2013, I think), and it lasted for a few weeks, and was naked eye for a while, at least with minimal light pollution.If you know what star it was, google it to see if it underwent a nova last night. If not, report what you saw to astronomers. There are any number of tricks your eyes could have played on you (and you mentioned several of them) but none are particularly more or less plausible than the others I think. I wouldn't really know for sure to be honest.