I agree.

The Peak of Seleukid Power

Antiochos Vs long reign was not a particularly expansionist one, but it was far from peaceful all the same.

In the east, the Wusun became serious protagonists in the 90s BC, raiding widely in the Ferghana Valley and Sogdiane. At more or less the same time, the Taxila-based Buddhists of Gandhara and Kaspeireia collapsed in the face of a renewed Sunga military onslaught; in the confusion, a military adventurer from Baktria, one Eupator, seized power, employing the sizable population of Greek colonists and refugees from the collapse of the Euthydemid state. Eupator I Soters Indohellenic kingdom crushed the Sunga armies in a decisive battle on the Akasines River in 87 BC and vouchsafed the states independence. Seleukid eastern resources were simply too taxed to deal with the new Indohellenic threat.

Further west, Seleukid power in Anatolia came under serious threat from Pharnakes III, ruler of the Pontic kingdom on the Black Sea coast. In the late 90s, Pharnakes had the opportunity to intervene in a succession crisis in Pantikapaion, which gave him more or less direct control over the kingdom of the Bosporan Kimmerioi far to the north. Afraid of the threat of a Pontos with the resources of the Crimea and the Galatians at its disposal, Antiochos Vs (third) son Demetrios, in the position of epistrategos of Anatolia, chose to preempt the Pontic king by invading Galatia in 88. The move disastrously backfired; the Seleukids failed to inflict a mortal wound on the Galatian tribes, which, led by the Tolistobogioi, turned to Pontos for alliance and aid, creating the very monster that Demetrios had feared. Pharnakes launched an invasion of Seleukid Kappadokia to try to cut the Royal Road and besieged Mazaka in 87; the Seleukid prince marched to the citys relief, but lost his life and his army in the ensuing battle.

But Pharnakes failed to reduce Mazaka all the same, and retreated back northwards upon the approach of further Seleukid armies. With the Galatians aid, he succeeded in destroying the kingdom of Bithynia, but quickly lost control of his erstwhile allies, who plundered widely in both Seleukid Phrygia and his own territories to the north. This distraction proved vital. By the time Pharnakes had gotten the Galatians under control with a series of costly military victories, Antiochos V had died of old age. His successor, Alexandros I Kallinikos (r. 82-69 BC), was significantly more energetic. After returning from his viceregal post in the East, Alexandros spent a year subduing the Galatians and then moved on to attack Pontos itself. At Komana, the Seleukid king crushed Pharnakes forces; the Pontic ruler was killed in the rout. Pontos brief era of glory petered out; it retained nominal independence, but the new king, Mithridates IV, was virtually powerless, and quickly lost control over the Greek cities of Pontos Paralios in the aftermath of the Battle of Komana.

Pharnakes brief military successes may not have brought the Seleukid rule in Anatolia to an end far from it but they had spawned a massive rebellion in Greece. The satrap of Makedonia was murdered in 83 BC and supplanted by a man claiming to be descended from the line of Antigonos, whose subordinates overran most of the Seleukid possessions west of the Hellespont. He resurrected the Hellenic League of Antigonos Doson, successfully convincing or coercing Sparta and the Aitolians to join him. At the same time, this Philippos VI raised a massive slave revolt in the Aegean littoral, proclaiming that he was the New Dionysos and promising an ill-defined Stoic paradise on Earth. The Seleukids retained little more than Athens, Akrokorinthos, and the aid of the Achaians, who were chiefly opposed to the Aitolians, Spartans, and Philippos quasi-Kleomenean attempts at social revolution.

Yet this Makedonian rebellion could do little against a real field army. Philippos VI turned out to be a cardboard general; when Alexandros I and his battle-hardened veterans landed in Attike in 79, the slave-bolstered Makedonian armies disintegrated. The mostly mercenary Spartan armies came to a sad end in 77 when they collapsed in the face of Alexandros veteran thorakitai and Galatian mercenaries at Pellana; Aitolian regulars and Makedonian rebels tried to rally at Elateia in Lokris, but they, too, were crushed. The long history of the Aitolian League ended in 76 with the (second) destruction of Thermon; Makedonias brief taste of independence ended not long thereafter.

Alexandros I rationalized the administration of Greece, dividing the territory into satrapies and eparchies and reducing the status of many hitherto independent poleis. This administrative work took up some years, during which he spent most of his time west of the Aegean. As such, he was in the perfect position to serve as a neutral arbiter in the widening conflicts in the western Mediterranean. Beginning with a revolt of Qarthadasts Brettian allies in 89, most of southern Italy had been engulfed in war to some extent or other, with Capua desperately attempting to rally some kind of reasonable defense against the vastly more powerful Qarthadast. Before 79, Qarthadastim diplomacy had kept the Samnites out of the struggle, but after the Campanian alliance lost control of Thourioi (again), the Samnites intervened. They, too, were militarily worsted by a Punic army in Lucania near Potentia.

As Qarthadastim armies overran much of southern Italy, Capua requested Seleukid military aid. Alexandros quickly responded, landing in Calabria in 72. Unsurprisingly, Seleukid armies spent much of their time establishing control over the country instead of fighting the Qarthadastim for several months. Only in 70 did Alexandros advance into Lucania, from where he had his pick of targets. One Bomilkar assembled an army to drive him out, but the Seleukids stole a march on the Qarthadastim and attacked the Punic concentrations at Pyxos. In a hard-fought fight, the battle was eventually decided when the Seleukid cavalry managed to pull off a double envelopment, after which the Punic army collapsed. The extent to which the Punic position in Italy collapsed after the Battle of Pyxos was not the result of battlefield defeat alone; political infighting in Africa played a part as well, as did sheer war exhaustion. In 69, the Qarthadastim sued for peace and retreated to Sicily. A few days after accepting the peace, Alexandros died in a hunting accident.

After Alexandros I Kallinikos, few Seleukid emperors felt secure enough to go off campaigning on one frontier or another; they preferred to remain in the imperial heartland and keep control of the territories that mattered most, while retaining the ability to monitor their satraps and generals. Antiochos VI Euergetes, who had been serving as something of a regent in Seleukeia while his father was off on campaign in the west, was easily able to slip into a leadership role. Instead, it became somewhat de rigueur for imperial princes to win their military laurels on the frontier while they were still waiting on the succession, then to return to the homeland once they were next in line. In times of internal stability and good interpersonal relations this worked quite well. Antiochos VI was perhaps the master of this particular skill, and it was during his extremely long reign (69-25 BC) that the Seleukid Empire reached its classical territorial height.

Antiochos VIs sons pursued aggressive territorial expansion, but their dirty secret was that much of the work of fighting had already been done by their predecessor Alexandros I. Pontos was fully absorbed into the empire along with Lesser (Pokr) Hayasdan in the sixties after Mithridates V foolishly took Alexandros death as a catalyst for rebellion; after the Yervanduni kings of Greater Hayasdan supported the rebellion, their own ramshackle armies were crushed, although much of the work was done by Scythian raiding from the north, not Seleukid armies. The puppet Haikaikan kings were then replaced by a Greek satrap in 37 BC after Samus II died childless. While Seleukos, the firstborn son of Antiochos and satrap of Baktria (before his untimely death in 41 BC) failed to extend the empire to the Indos, he campaigned against the Eupatrid Indohellenic kingdom and forced Straton II, the king, to render tribute.

It has long been a trope that the Seleukid state reached a cultural height under Antiochos VI, whatever thats supposed to mean. Certainly, the literary and artistic output of the period was impressive, in large part due to extensive imperial patronage. But much of what was produced was countercultural, in the case of the flowering of Cynic philosophy, or simply individual for the cult of the individual had been gaining steam throughout the Hellenistic era, and with the ultimate triumph of the monolithic Seleukid state, many men chose to literally carve themselves a place in history. Many of these men were merchants, enriched by the wave of Seleukid conquests and the trade that came with it; others were generals or magistrates plundering the territories of their remit. But while the volume of statues of individuals for public display may have been greater than at any time before in Greek history, the colossal size of imperial constructions dwarfed everything else. The palace complex at Seleukeia, the temple of Olympian Zeus at Athens, the vast stoa at Hekatompylos, and the center for the pan-imperial games at Apameia in Syria what defined these Seleukid constructions, more than anything else, was their colossal size. Wags then and later said that being big made up for their lack of intrinsic architectural merit but size, of course, has a merit all its own.

In terms of literary output, perhaps the most famous piece, other than the histories of Aristonikos and Dioskourides Athenaios, was the Herakleiad, composed by Apollonios Ekbatanikos, which tied the stories of Herakles in Asia together into a coherent story, replete with pointed references to the Seleukid conquests in Iran and Central Asia. As a literary construct, it has its merits, and certainly has inspired its share of imitators and borrowers over the ages (the scene in which Herakles storms the Khyber Pass being the most evocative), but perhaps his most enduring legacy, though, was to enrage generations of classics students who confused him with Apollonios Rhodios, author of the Argonautika. After having been left somewhat by the wayside for a century, heroic poetry experienced a resurgence in the literary circles of Athens, Antiocheia, Alexandreia, and Seleukeia though Anatolian and Median grandees were still quite fond of the idylls and pastoral poems that had always been popular amongst rural aristocracy.

In the wider world, high Seleukid art and architecture had an interesting impact. Already by 100 BC, but even more stridently after it, Qarthadastim merchants and many Italian notables began to experience the artistic life of the Greek East and came away wanting much more; conveniently, around the same time, the technology for reproducing marble via something rather akin to the lost-wax process that permitted the widespread copying of bronzes came into being, so that the well to do of the Seleukid periphery could have their own versions of sculptures by the Old Masters, or whatever was currently in vogue in the oikoumene, in both bronze and the more prestigious marble. While a Punic aristocrat couldnt get his hands on Pentelic marble or Egyptian granite (unless he were very, very lucky or very, very rich), even a slightly cheaper substitute for either would be a quite impressive way to one-up the neighbors. It was around the same time that mosaic art started to show up in Africa and Italy, although it was not as advanced as the stuff further east (for instance, employing roughly-cut stones instead of tesserae).

State and Religious Practice in the Greek Oikoumene

If the late first century saw the Seleukid Empire reach new territorial heights, as had not been seen since the time of Alexander, culturally it has been described as having been in something of a decadent malaise. Like most claims of decadence, this has both true and false elements to it. Indeed, the Hellenistic period was one which saw the emergence of several new religions and their popularization across the oikoumene.

Antiochos Vs declaration in 104 BC that he was a God Manifest, epiphanes, helped to throw the religious and philosophical contradictions of the Hellenistic age into sharp relief. He was not the first dynast to have declared himself a living god. Alexander had tried, but had been ridiculed for his trouble, and even he hadnt taken his godhood particularly seriously. (When in India, he had been wounded, and a nearby soldier had quoted Homer, Ichor, such as flows from the blessed gods. The king had tartly cut him short, growling, Thats not ichor thats blood.)

In Egypt, the Ptolemaioi had also declared themselves gods manifest, not merely to the indigenous Egyptians but to their Greek subjects as well. Ptolemaios II Philadelphos had been the first to institute a Greek ruler-cult, which pulled some ceremonial from the pharaonic tradition, but was chiefly meant for the consumption of the Greek, Syrian, and Galatian colonists along the Nile. Yet the colonists themselves seem not to have particularly believed that the Ptolemaic kings were, in fact, deities but pragmatically worshiped them all the same. In that way, the Ptolemaic ruler-cult was less religious than areligious; its supplications were directed at beings who actually could intervene regularly in ones daily life, not the distant Olympians who were notoriously mercurial, if they showed up at all.

Many of the same elements showed up in the ruler cult that Antiochos established. Its never been particularly clear whether Antiochos himself was megalomaniacal to believe that he actually was divine, but that was almost a red herring. Instead, what mattered most was that he was a patron deserving of supplication, like the gods of Olympos, but who seemed much more likely to actually respond to pleas for aid. The Seleukids had already experimented with this during the reign of Antiochos III, who had made his wife Laodike a goddess in parts of Asia Minor. Antiochos simply extended the idea.

The institution of the formal ruler-cult and its widespread acceptance did not mean that it was universal or even unopposed, far from it. Philosophically, the Cynics, as they were wont to do, opposed the Seleukid divine ruler-cult out of their simple affinity for counter-culture; because of this, several philosophical concepts were increasingly mixed with Olympian worship, with unclear results. But the Olympians found much support in Greece itself provincial gods for a provincial land, no longer the heart of Mediterranean commerce and trade or the heartland of empires. While cities like Athens retained much of their traditional and cultural importance, politically and economically they were being passed by. Even though the Seleukid kings spent many talents in Greece for patronage Seleukos IV had completed the great temple of Olympian Zeus at Athens (which had been started by the Peisistratids in the sixth century) and they were nothing compared to the vast funds spent on the development of the Syrian coast, or the construction of the massive palace complex at Seleukeia on the Tigris.

Antiochos never pushed for exclusive worship of his ruler-cult, nor did he employ it as a flimsy justification for raiding and confiscating his subjects property. There were no pogroms or anything like it under his reign. Indeed, the Jews, famously disinterested in the Greek pantheon (if very interested in Greek philosophy, language, art, and medicine), continued to be crucial to Seleukid rule in Anatolia and Central Asia, where they made up a large proportion of colonists.

The worship of other famous Hellenistic cults also continued unabated, the most popular of which was that of Tyche, Fortune (usually Agathe Tyche, Good Fortune); Dionysos was also popular, especially in Anatolia, where his resurrection and savior aspects were played up. Apollon-worship remained popular within the Seleukid state, unsurprisingly, as Seleukos I had claimed to be descended from the sun god, and continued to be one of the chief coin-types employed by the kings. The worship of Sarapis and Isis continued to spread out of Egypt, where it had been encouraged by the late Ptolemaioi. In Areia and Baktria, the cults of Artemis-Anahita and Zeus-Ahura Mazda were widespread. All over the Seleukid Empire, one could find heroons, shrines to individual heroes, somewhat associated with the worship of Herakles. In short, the diverse pattern of worship that had obtained before the institution of the Seleukid ruler-cult largely continued for the time being.

Eurasia During the Seleukid Apogee

Insofar as the Gallic groupings around the Aeduoi and Auernoi can be referred to as polities, they expanded their reach and intermittently warred with each other during this period; the Auernoi in particular achieved military success under the verrix Cadeyrn. The coalescence of groupings of Belgae (especially the Tongroi and Manapioi) and, across the Rhine, the Somnonoz, were also relevant, although neither group really made much difference to goings-on further south. Of particular interest was the development of basic professional soldiers throughout much of Celtic Gaul, as the monetary economy expanded and soldiers pay became viable; the expanding Massiliot economy may have had something to do with this, as the Massiliots were close partners with the Auernoi kings. Frequently cited in support of this is the growth of the cult of Dionysos-Cernunnos, a syncretic Celtohellenic deity worshiped primarily in Massilia and the growing oppidum of Gergovia.

Although the Qarthadastim spent three decades in an ultimately counterproductive war in south Italy, their efforts in Iberia were much more profitable. After the bloody conquest of Turdetania in the 90s and 80s, Punic diplomats negotiated agreements with several groups in Carpetania and Turdulia and brought more and more into their alliance. The perception of the Qarthadastim as relatively disinterested allies with light hands aided expansion, as many Iberian groups were fearful of the growing power of the Celtiberian tribal alliance headed by Numantia (which included many groups that were not Celtiberi, but that moniker is most convenient). Despite limited attention due to political squabbles back home, the Qarthadastim gave a good accounting of themselves in a dust-up with the Celtiberians in the 30s BC; after the creation of a provincial administration with wide-ranging extrademocratic remit in 33 BC, it appeared as though the Qarthadastim were going to renew the contest in earnest.

The jury-rigged coalition of Insubres didnt last much longer, and soon broke apart, with the Veneti going their own way in the 60s BC. Even though Rome was dead, the Rasna leagues that replaced it in northern Italy could still outmobilize the Gauls of the Po Valley. Etruscan warlords in Umbria took advantage of the collapse of the Insubres hegemony in the 60s to retake and resettle Aemilia. At the same time, the loose Etruscan federation began to slowly metamorphose into something rather similar to the Greek Achaian League, spearheaded by the statesman Silius Vetulonius and spurred by a defeat in a naval war with the Qarthadastim over Alalia (which Qarthadast reclaimed in 47) and Capuas protagonism in Latium, where it dismembered what was left of the local Rasna league. Under Vetulonius successor at the head of the Rasna federation, Numerius Pontidius, the Etruscans successfully established suzerainty over the Ligurians and fought a victorious war with the Insubres to retain their conquest.

Things in Central Asia changed little after the initially furious onslaught of the Wusun. By skillful diplomacy, the satrap of Baktria, the Seleukid prince Demetrios, detached the Haomavarga Saka from the Wusun confederacy in 44; shortly thereafter, he elected to conquer the buffer state of Chach, north of the Iaxartes. Chach, which was fairly urbanized, put up stiff military resistance but was conquered in 39 and inventively refounded as Demetrias. The Wusun responded by raiding widely both north and south of the Iaxartes, but to little effect.

Eupator Is successful hijack of the Gandharan-Kaspeireian Buddhist state was remarkable, but it had been ensured by the large-scale migration of Baktrian Greeks (and Hellenized Baktrians) into India from the west. These men, who had found gainful employment as heavy infantry mercenaries with unequaled staying power, had, along with the guild-warriors common in western India, provided the bulk of the Gandharan professional infantry. Eupator introduced even more migratory Greeks into the country and refounded several cities after the Greek fashion, but continued to play Janus, representing himself as a savior to the native Indian population with Kharosthi-script coinage. Whether astute political calculation or genuine belief (or both), his adoption of Buddhism went a long way towards ensuring the domestic foundations of his regime.

The Eupatrid kings that followed Eupator I were perhaps less able than he; Straton II, in particular, was somewhat feckless and incompetent. They never had enough Greek manpower to seriously consider invading the Sunga Empire, and only cautiously established connections with the peoples of Abiria and the other territories further south on the Indos. That dynamic seemed ready to change as the 30s BC wound down, for the Sunga Empire itself was on its last legs, hemorrhaging manpower and territory after several defeats at the hands of the Satavahanas of Andhra. (Interestingly, state and society were increasingly decoupled in the late Sunga state. Magadhi culture underwent something of a flowering around this time period, with the collation of several literary epics and the emergence of new styles of art based partly on Indohellenic influences.)

The Han hit a low point in 91 BC when Xuandi, the successor to Chongdi, was murdered by his officials after attempting to make his own appointments; the minor rebellion that this kicked off saw the Yuezhi intervene and briefly (for one week) besiege Changan. It didnt take, fortunately, and the reign of Zhaodi (91-76 BC) saw the Han get back a significant measure of their old power and prominence. The rebellions were suppressed, and the Han even launched an invasion of Minyue, which remarkably succeeded. Zhaodis generals, chief among them Zhu He, then successfully beat back the inevitable Yuezhi raids. The regime was immobilized by aristocratic intrigues surrounding the Xu and Huo families in Zhaodis later years, but such was the price of success.

Zhaodis great-grandson, Mingdi, rose to power in 46 BC after a peasant siege of Changan caused the assassination of his unfortunate father Aidi; he conciliated the rebels, and a few weeks later had them all killed (or so the story goes) by one of the frontier armies. The streak of ruthlessness served him well in crushing further dissent; he broke up another plot two years later by having the official Dong Jia boiled alive as a particularly esoteric and gruesome warning. It was under his reign that the conquest of the south was completed. In 40 BC, the emperor launched the invasion of the rebel state of Nanyue, which had been tottering on the brink of collapse for some time under the rulership of the ineffectual Zhao family. The conquest was swift and brutal; after only a few field battles and a successful siege of the capital, Panyu, the last Nanyue emperor was murdered and the state was effectively decapitated. Cleanup lasted significantly longer, as the native Yue population had been in revolt against the Chinese rulers and administrators for quite some time, and werent about to quiet down because a new set of foreigners was in the house. Han rule was still shaky in 25 BC, with several small armies detailed to search-and-destroy missions throughout Lingnan.

The End of the Seleukid Golden Age

In 24 BC, Antiochos VI died of old age. His eldest son, Demetrios, had command of the Baktrian field army and the substantial resources of the further East; he seemed a clear heir presumptive. Personal animosity, though, intervened. With Antiochos alive, the poor relations of the various brothers had been submerged, but with the issue of the succession out in the open, civil war was in the offing. Much of the Syrian and Babylonian government supported the satrap of Armenia, the fourth brother, Attalos. Further west, the youngest brother (of six), Seleukos, had turned Makedonia and Greece into a personal satrapal seat from Athens, and loathed Attalos; he was likely to play on Makedonian and Hellenic secessionism if Attalos were crowned.

Antiochos VIs funeral games would spell the end of the Seleukid Empires hegemony.

The Peak of Seleukid Power

Antiochos Vs long reign was not a particularly expansionist one, but it was far from peaceful all the same.

In the east, the Wusun became serious protagonists in the 90s BC, raiding widely in the Ferghana Valley and Sogdiane. At more or less the same time, the Taxila-based Buddhists of Gandhara and Kaspeireia collapsed in the face of a renewed Sunga military onslaught; in the confusion, a military adventurer from Baktria, one Eupator, seized power, employing the sizable population of Greek colonists and refugees from the collapse of the Euthydemid state. Eupator I Soters Indohellenic kingdom crushed the Sunga armies in a decisive battle on the Akasines River in 87 BC and vouchsafed the states independence. Seleukid eastern resources were simply too taxed to deal with the new Indohellenic threat.

Further west, Seleukid power in Anatolia came under serious threat from Pharnakes III, ruler of the Pontic kingdom on the Black Sea coast. In the late 90s, Pharnakes had the opportunity to intervene in a succession crisis in Pantikapaion, which gave him more or less direct control over the kingdom of the Bosporan Kimmerioi far to the north. Afraid of the threat of a Pontos with the resources of the Crimea and the Galatians at its disposal, Antiochos Vs (third) son Demetrios, in the position of epistrategos of Anatolia, chose to preempt the Pontic king by invading Galatia in 88. The move disastrously backfired; the Seleukids failed to inflict a mortal wound on the Galatian tribes, which, led by the Tolistobogioi, turned to Pontos for alliance and aid, creating the very monster that Demetrios had feared. Pharnakes launched an invasion of Seleukid Kappadokia to try to cut the Royal Road and besieged Mazaka in 87; the Seleukid prince marched to the citys relief, but lost his life and his army in the ensuing battle.

But Pharnakes failed to reduce Mazaka all the same, and retreated back northwards upon the approach of further Seleukid armies. With the Galatians aid, he succeeded in destroying the kingdom of Bithynia, but quickly lost control of his erstwhile allies, who plundered widely in both Seleukid Phrygia and his own territories to the north. This distraction proved vital. By the time Pharnakes had gotten the Galatians under control with a series of costly military victories, Antiochos V had died of old age. His successor, Alexandros I Kallinikos (r. 82-69 BC), was significantly more energetic. After returning from his viceregal post in the East, Alexandros spent a year subduing the Galatians and then moved on to attack Pontos itself. At Komana, the Seleukid king crushed Pharnakes forces; the Pontic ruler was killed in the rout. Pontos brief era of glory petered out; it retained nominal independence, but the new king, Mithridates IV, was virtually powerless, and quickly lost control over the Greek cities of Pontos Paralios in the aftermath of the Battle of Komana.

Pharnakes brief military successes may not have brought the Seleukid rule in Anatolia to an end far from it but they had spawned a massive rebellion in Greece. The satrap of Makedonia was murdered in 83 BC and supplanted by a man claiming to be descended from the line of Antigonos, whose subordinates overran most of the Seleukid possessions west of the Hellespont. He resurrected the Hellenic League of Antigonos Doson, successfully convincing or coercing Sparta and the Aitolians to join him. At the same time, this Philippos VI raised a massive slave revolt in the Aegean littoral, proclaiming that he was the New Dionysos and promising an ill-defined Stoic paradise on Earth. The Seleukids retained little more than Athens, Akrokorinthos, and the aid of the Achaians, who were chiefly opposed to the Aitolians, Spartans, and Philippos quasi-Kleomenean attempts at social revolution.

Yet this Makedonian rebellion could do little against a real field army. Philippos VI turned out to be a cardboard general; when Alexandros I and his battle-hardened veterans landed in Attike in 79, the slave-bolstered Makedonian armies disintegrated. The mostly mercenary Spartan armies came to a sad end in 77 when they collapsed in the face of Alexandros veteran thorakitai and Galatian mercenaries at Pellana; Aitolian regulars and Makedonian rebels tried to rally at Elateia in Lokris, but they, too, were crushed. The long history of the Aitolian League ended in 76 with the (second) destruction of Thermon; Makedonias brief taste of independence ended not long thereafter.

Alexandros I rationalized the administration of Greece, dividing the territory into satrapies and eparchies and reducing the status of many hitherto independent poleis. This administrative work took up some years, during which he spent most of his time west of the Aegean. As such, he was in the perfect position to serve as a neutral arbiter in the widening conflicts in the western Mediterranean. Beginning with a revolt of Qarthadasts Brettian allies in 89, most of southern Italy had been engulfed in war to some extent or other, with Capua desperately attempting to rally some kind of reasonable defense against the vastly more powerful Qarthadast. Before 79, Qarthadastim diplomacy had kept the Samnites out of the struggle, but after the Campanian alliance lost control of Thourioi (again), the Samnites intervened. They, too, were militarily worsted by a Punic army in Lucania near Potentia.

As Qarthadastim armies overran much of southern Italy, Capua requested Seleukid military aid. Alexandros quickly responded, landing in Calabria in 72. Unsurprisingly, Seleukid armies spent much of their time establishing control over the country instead of fighting the Qarthadastim for several months. Only in 70 did Alexandros advance into Lucania, from where he had his pick of targets. One Bomilkar assembled an army to drive him out, but the Seleukids stole a march on the Qarthadastim and attacked the Punic concentrations at Pyxos. In a hard-fought fight, the battle was eventually decided when the Seleukid cavalry managed to pull off a double envelopment, after which the Punic army collapsed. The extent to which the Punic position in Italy collapsed after the Battle of Pyxos was not the result of battlefield defeat alone; political infighting in Africa played a part as well, as did sheer war exhaustion. In 69, the Qarthadastim sued for peace and retreated to Sicily. A few days after accepting the peace, Alexandros died in a hunting accident.

After Alexandros I Kallinikos, few Seleukid emperors felt secure enough to go off campaigning on one frontier or another; they preferred to remain in the imperial heartland and keep control of the territories that mattered most, while retaining the ability to monitor their satraps and generals. Antiochos VI Euergetes, who had been serving as something of a regent in Seleukeia while his father was off on campaign in the west, was easily able to slip into a leadership role. Instead, it became somewhat de rigueur for imperial princes to win their military laurels on the frontier while they were still waiting on the succession, then to return to the homeland once they were next in line. In times of internal stability and good interpersonal relations this worked quite well. Antiochos VI was perhaps the master of this particular skill, and it was during his extremely long reign (69-25 BC) that the Seleukid Empire reached its classical territorial height.

Antiochos VIs sons pursued aggressive territorial expansion, but their dirty secret was that much of the work of fighting had already been done by their predecessor Alexandros I. Pontos was fully absorbed into the empire along with Lesser (Pokr) Hayasdan in the sixties after Mithridates V foolishly took Alexandros death as a catalyst for rebellion; after the Yervanduni kings of Greater Hayasdan supported the rebellion, their own ramshackle armies were crushed, although much of the work was done by Scythian raiding from the north, not Seleukid armies. The puppet Haikaikan kings were then replaced by a Greek satrap in 37 BC after Samus II died childless. While Seleukos, the firstborn son of Antiochos and satrap of Baktria (before his untimely death in 41 BC) failed to extend the empire to the Indos, he campaigned against the Eupatrid Indohellenic kingdom and forced Straton II, the king, to render tribute.

It has long been a trope that the Seleukid state reached a cultural height under Antiochos VI, whatever thats supposed to mean. Certainly, the literary and artistic output of the period was impressive, in large part due to extensive imperial patronage. But much of what was produced was countercultural, in the case of the flowering of Cynic philosophy, or simply individual for the cult of the individual had been gaining steam throughout the Hellenistic era, and with the ultimate triumph of the monolithic Seleukid state, many men chose to literally carve themselves a place in history. Many of these men were merchants, enriched by the wave of Seleukid conquests and the trade that came with it; others were generals or magistrates plundering the territories of their remit. But while the volume of statues of individuals for public display may have been greater than at any time before in Greek history, the colossal size of imperial constructions dwarfed everything else. The palace complex at Seleukeia, the temple of Olympian Zeus at Athens, the vast stoa at Hekatompylos, and the center for the pan-imperial games at Apameia in Syria what defined these Seleukid constructions, more than anything else, was their colossal size. Wags then and later said that being big made up for their lack of intrinsic architectural merit but size, of course, has a merit all its own.

In terms of literary output, perhaps the most famous piece, other than the histories of Aristonikos and Dioskourides Athenaios, was the Herakleiad, composed by Apollonios Ekbatanikos, which tied the stories of Herakles in Asia together into a coherent story, replete with pointed references to the Seleukid conquests in Iran and Central Asia. As a literary construct, it has its merits, and certainly has inspired its share of imitators and borrowers over the ages (the scene in which Herakles storms the Khyber Pass being the most evocative), but perhaps his most enduring legacy, though, was to enrage generations of classics students who confused him with Apollonios Rhodios, author of the Argonautika. After having been left somewhat by the wayside for a century, heroic poetry experienced a resurgence in the literary circles of Athens, Antiocheia, Alexandreia, and Seleukeia though Anatolian and Median grandees were still quite fond of the idylls and pastoral poems that had always been popular amongst rural aristocracy.

In the wider world, high Seleukid art and architecture had an interesting impact. Already by 100 BC, but even more stridently after it, Qarthadastim merchants and many Italian notables began to experience the artistic life of the Greek East and came away wanting much more; conveniently, around the same time, the technology for reproducing marble via something rather akin to the lost-wax process that permitted the widespread copying of bronzes came into being, so that the well to do of the Seleukid periphery could have their own versions of sculptures by the Old Masters, or whatever was currently in vogue in the oikoumene, in both bronze and the more prestigious marble. While a Punic aristocrat couldnt get his hands on Pentelic marble or Egyptian granite (unless he were very, very lucky or very, very rich), even a slightly cheaper substitute for either would be a quite impressive way to one-up the neighbors. It was around the same time that mosaic art started to show up in Africa and Italy, although it was not as advanced as the stuff further east (for instance, employing roughly-cut stones instead of tesserae).

State and Religious Practice in the Greek Oikoumene

If the late first century saw the Seleukid Empire reach new territorial heights, as had not been seen since the time of Alexander, culturally it has been described as having been in something of a decadent malaise. Like most claims of decadence, this has both true and false elements to it. Indeed, the Hellenistic period was one which saw the emergence of several new religions and their popularization across the oikoumene.

Antiochos Vs declaration in 104 BC that he was a God Manifest, epiphanes, helped to throw the religious and philosophical contradictions of the Hellenistic age into sharp relief. He was not the first dynast to have declared himself a living god. Alexander had tried, but had been ridiculed for his trouble, and even he hadnt taken his godhood particularly seriously. (When in India, he had been wounded, and a nearby soldier had quoted Homer, Ichor, such as flows from the blessed gods. The king had tartly cut him short, growling, Thats not ichor thats blood.)

In Egypt, the Ptolemaioi had also declared themselves gods manifest, not merely to the indigenous Egyptians but to their Greek subjects as well. Ptolemaios II Philadelphos had been the first to institute a Greek ruler-cult, which pulled some ceremonial from the pharaonic tradition, but was chiefly meant for the consumption of the Greek, Syrian, and Galatian colonists along the Nile. Yet the colonists themselves seem not to have particularly believed that the Ptolemaic kings were, in fact, deities but pragmatically worshiped them all the same. In that way, the Ptolemaic ruler-cult was less religious than areligious; its supplications were directed at beings who actually could intervene regularly in ones daily life, not the distant Olympians who were notoriously mercurial, if they showed up at all.

Many of the same elements showed up in the ruler cult that Antiochos established. Its never been particularly clear whether Antiochos himself was megalomaniacal to believe that he actually was divine, but that was almost a red herring. Instead, what mattered most was that he was a patron deserving of supplication, like the gods of Olympos, but who seemed much more likely to actually respond to pleas for aid. The Seleukids had already experimented with this during the reign of Antiochos III, who had made his wife Laodike a goddess in parts of Asia Minor. Antiochos simply extended the idea.

The institution of the formal ruler-cult and its widespread acceptance did not mean that it was universal or even unopposed, far from it. Philosophically, the Cynics, as they were wont to do, opposed the Seleukid divine ruler-cult out of their simple affinity for counter-culture; because of this, several philosophical concepts were increasingly mixed with Olympian worship, with unclear results. But the Olympians found much support in Greece itself provincial gods for a provincial land, no longer the heart of Mediterranean commerce and trade or the heartland of empires. While cities like Athens retained much of their traditional and cultural importance, politically and economically they were being passed by. Even though the Seleukid kings spent many talents in Greece for patronage Seleukos IV had completed the great temple of Olympian Zeus at Athens (which had been started by the Peisistratids in the sixth century) and they were nothing compared to the vast funds spent on the development of the Syrian coast, or the construction of the massive palace complex at Seleukeia on the Tigris.

Antiochos never pushed for exclusive worship of his ruler-cult, nor did he employ it as a flimsy justification for raiding and confiscating his subjects property. There were no pogroms or anything like it under his reign. Indeed, the Jews, famously disinterested in the Greek pantheon (if very interested in Greek philosophy, language, art, and medicine), continued to be crucial to Seleukid rule in Anatolia and Central Asia, where they made up a large proportion of colonists.

The worship of other famous Hellenistic cults also continued unabated, the most popular of which was that of Tyche, Fortune (usually Agathe Tyche, Good Fortune); Dionysos was also popular, especially in Anatolia, where his resurrection and savior aspects were played up. Apollon-worship remained popular within the Seleukid state, unsurprisingly, as Seleukos I had claimed to be descended from the sun god, and continued to be one of the chief coin-types employed by the kings. The worship of Sarapis and Isis continued to spread out of Egypt, where it had been encouraged by the late Ptolemaioi. In Areia and Baktria, the cults of Artemis-Anahita and Zeus-Ahura Mazda were widespread. All over the Seleukid Empire, one could find heroons, shrines to individual heroes, somewhat associated with the worship of Herakles. In short, the diverse pattern of worship that had obtained before the institution of the Seleukid ruler-cult largely continued for the time being.

Eurasia During the Seleukid Apogee

Insofar as the Gallic groupings around the Aeduoi and Auernoi can be referred to as polities, they expanded their reach and intermittently warred with each other during this period; the Auernoi in particular achieved military success under the verrix Cadeyrn. The coalescence of groupings of Belgae (especially the Tongroi and Manapioi) and, across the Rhine, the Somnonoz, were also relevant, although neither group really made much difference to goings-on further south. Of particular interest was the development of basic professional soldiers throughout much of Celtic Gaul, as the monetary economy expanded and soldiers pay became viable; the expanding Massiliot economy may have had something to do with this, as the Massiliots were close partners with the Auernoi kings. Frequently cited in support of this is the growth of the cult of Dionysos-Cernunnos, a syncretic Celtohellenic deity worshiped primarily in Massilia and the growing oppidum of Gergovia.

Although the Qarthadastim spent three decades in an ultimately counterproductive war in south Italy, their efforts in Iberia were much more profitable. After the bloody conquest of Turdetania in the 90s and 80s, Punic diplomats negotiated agreements with several groups in Carpetania and Turdulia and brought more and more into their alliance. The perception of the Qarthadastim as relatively disinterested allies with light hands aided expansion, as many Iberian groups were fearful of the growing power of the Celtiberian tribal alliance headed by Numantia (which included many groups that were not Celtiberi, but that moniker is most convenient). Despite limited attention due to political squabbles back home, the Qarthadastim gave a good accounting of themselves in a dust-up with the Celtiberians in the 30s BC; after the creation of a provincial administration with wide-ranging extrademocratic remit in 33 BC, it appeared as though the Qarthadastim were going to renew the contest in earnest.

The jury-rigged coalition of Insubres didnt last much longer, and soon broke apart, with the Veneti going their own way in the 60s BC. Even though Rome was dead, the Rasna leagues that replaced it in northern Italy could still outmobilize the Gauls of the Po Valley. Etruscan warlords in Umbria took advantage of the collapse of the Insubres hegemony in the 60s to retake and resettle Aemilia. At the same time, the loose Etruscan federation began to slowly metamorphose into something rather similar to the Greek Achaian League, spearheaded by the statesman Silius Vetulonius and spurred by a defeat in a naval war with the Qarthadastim over Alalia (which Qarthadast reclaimed in 47) and Capuas protagonism in Latium, where it dismembered what was left of the local Rasna league. Under Vetulonius successor at the head of the Rasna federation, Numerius Pontidius, the Etruscans successfully established suzerainty over the Ligurians and fought a victorious war with the Insubres to retain their conquest.

Things in Central Asia changed little after the initially furious onslaught of the Wusun. By skillful diplomacy, the satrap of Baktria, the Seleukid prince Demetrios, detached the Haomavarga Saka from the Wusun confederacy in 44; shortly thereafter, he elected to conquer the buffer state of Chach, north of the Iaxartes. Chach, which was fairly urbanized, put up stiff military resistance but was conquered in 39 and inventively refounded as Demetrias. The Wusun responded by raiding widely both north and south of the Iaxartes, but to little effect.

Eupator Is successful hijack of the Gandharan-Kaspeireian Buddhist state was remarkable, but it had been ensured by the large-scale migration of Baktrian Greeks (and Hellenized Baktrians) into India from the west. These men, who had found gainful employment as heavy infantry mercenaries with unequaled staying power, had, along with the guild-warriors common in western India, provided the bulk of the Gandharan professional infantry. Eupator introduced even more migratory Greeks into the country and refounded several cities after the Greek fashion, but continued to play Janus, representing himself as a savior to the native Indian population with Kharosthi-script coinage. Whether astute political calculation or genuine belief (or both), his adoption of Buddhism went a long way towards ensuring the domestic foundations of his regime.

The Eupatrid kings that followed Eupator I were perhaps less able than he; Straton II, in particular, was somewhat feckless and incompetent. They never had enough Greek manpower to seriously consider invading the Sunga Empire, and only cautiously established connections with the peoples of Abiria and the other territories further south on the Indos. That dynamic seemed ready to change as the 30s BC wound down, for the Sunga Empire itself was on its last legs, hemorrhaging manpower and territory after several defeats at the hands of the Satavahanas of Andhra. (Interestingly, state and society were increasingly decoupled in the late Sunga state. Magadhi culture underwent something of a flowering around this time period, with the collation of several literary epics and the emergence of new styles of art based partly on Indohellenic influences.)

The Han hit a low point in 91 BC when Xuandi, the successor to Chongdi, was murdered by his officials after attempting to make his own appointments; the minor rebellion that this kicked off saw the Yuezhi intervene and briefly (for one week) besiege Changan. It didnt take, fortunately, and the reign of Zhaodi (91-76 BC) saw the Han get back a significant measure of their old power and prominence. The rebellions were suppressed, and the Han even launched an invasion of Minyue, which remarkably succeeded. Zhaodis generals, chief among them Zhu He, then successfully beat back the inevitable Yuezhi raids. The regime was immobilized by aristocratic intrigues surrounding the Xu and Huo families in Zhaodis later years, but such was the price of success.

Zhaodis great-grandson, Mingdi, rose to power in 46 BC after a peasant siege of Changan caused the assassination of his unfortunate father Aidi; he conciliated the rebels, and a few weeks later had them all killed (or so the story goes) by one of the frontier armies. The streak of ruthlessness served him well in crushing further dissent; he broke up another plot two years later by having the official Dong Jia boiled alive as a particularly esoteric and gruesome warning. It was under his reign that the conquest of the south was completed. In 40 BC, the emperor launched the invasion of the rebel state of Nanyue, which had been tottering on the brink of collapse for some time under the rulership of the ineffectual Zhao family. The conquest was swift and brutal; after only a few field battles and a successful siege of the capital, Panyu, the last Nanyue emperor was murdered and the state was effectively decapitated. Cleanup lasted significantly longer, as the native Yue population had been in revolt against the Chinese rulers and administrators for quite some time, and werent about to quiet down because a new set of foreigners was in the house. Han rule was still shaky in 25 BC, with several small armies detailed to search-and-destroy missions throughout Lingnan.

The End of the Seleukid Golden Age

In 24 BC, Antiochos VI died of old age. His eldest son, Demetrios, had command of the Baktrian field army and the substantial resources of the further East; he seemed a clear heir presumptive. Personal animosity, though, intervened. With Antiochos alive, the poor relations of the various brothers had been submerged, but with the issue of the succession out in the open, civil war was in the offing. Much of the Syrian and Babylonian government supported the satrap of Armenia, the fourth brother, Attalos. Further west, the youngest brother (of six), Seleukos, had turned Makedonia and Greece into a personal satrapal seat from Athens, and loathed Attalos; he was likely to play on Makedonian and Hellenic secessionism if Attalos were crowned.

Antiochos VIs funeral games would spell the end of the Seleukid Empires hegemony.

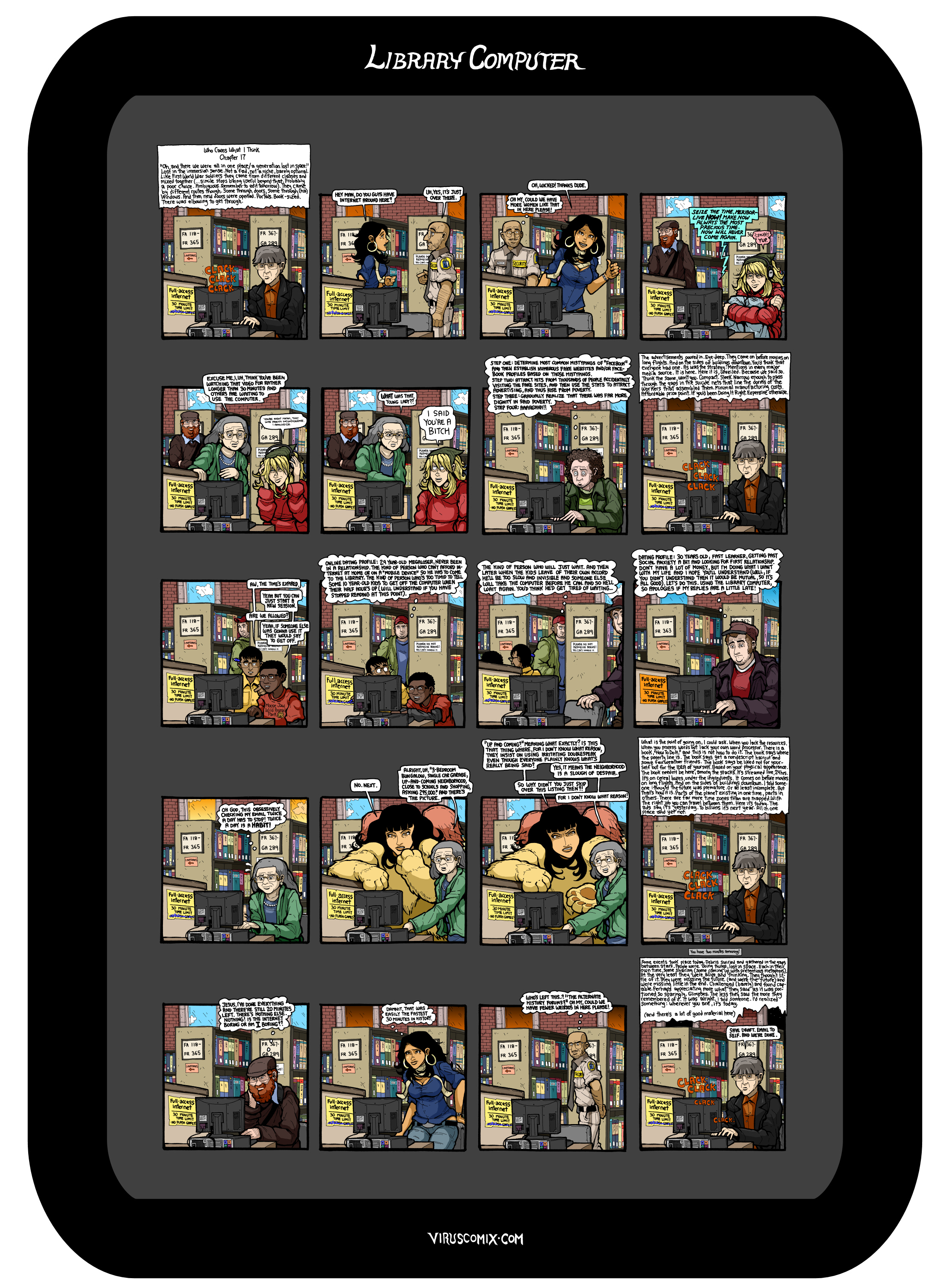

Spoiler World Map 25 BC :