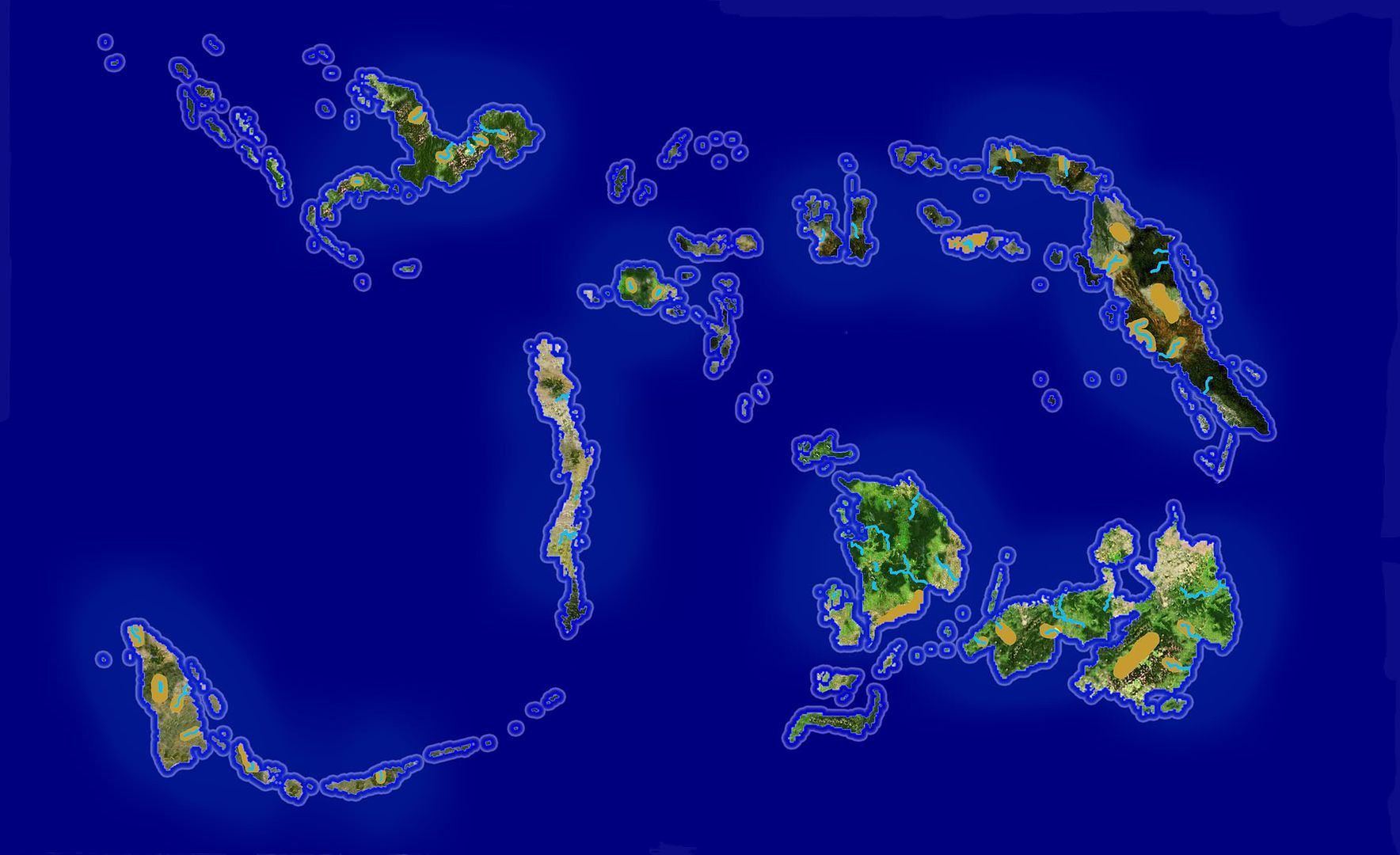

Sisisnc is a region of environmental and societal complexity. It encompasses a collage of sparsely forested highlands, damp lowland jungle, ubiquitous coastal valleys and endless bodies of water. It runs for approximately 5000kms from the most north western island through the equator and onto the south eastern most island. Throughout this region are represented societies of many different socio-economic levels – from hunters and gatherers through to tribal farmers and finally to stratified chiefdoms with knowledge of iron and bronze working and increasingly complex farming techniques. Cutting across these socio-economic levels are cultural differences. These differences reflect geographic isolation, a vast array of bodies of water, bisecting mountain ranges and the flow of human movements, colonisations and invasions.

Sisisnc’s strengths are in three key areas, its skilled farmers, metallurgists and sailors. Its denizens are innovative farmers. This is evidenced by their progression away from dry shifting millet cultivation in the highlands in the core towards wet sedentary rice farming in the rich alluvial plains and its domestication of pigs and chickens. Its metallurgists have already mastered bronze working in all but the most distant areas and have in the core begun to produce small amounts of ferrous iron. Its people, typically measured in boatloads along the coasts, are master sailors, capable of traversing the many water bodies in double outrigger canoes and setting sail for new shores at the slightest pretext.

Cultivation is divided into three distinct types. The oldest method is the farming of millet in the uplands. Famers using this method typically clear a patch of forest then burn it every year. Planting consists of digging holes with pointed sticks followed by the introduction of the seeds. The burn adds nutrients to the soil allowing a limited number of crops to be harvested as the nutrients added wash away. The method has relatively constant yields with little scope for surpluses and population is correspondingly low. These populations are also not confined to any particular geographic feature and tend to move in limited local migration a cycle which tends to militate against the formation of states or other sedentary enterprises. The second oldest method is the cultivation of rice in the highlands. Farmers using this method also engage in the same ‘slash and burn’ and seed introduction practices as millet cultivators. The area under seed however is carefully selected with farmers looking for sloping hills for natural drainage. Yields are somewhat higher than millet, with two crops per season common, with increased scope for surpluses. The limitation placed on the selection of sites introduces a degree of scarcity into the selection of land. It is possible to say that in general that the constraints on production were not due to arable land but to a paucity of labour. The transition from highland rice farming to lowland rice farming can perhaps be attributed to population pressure with competing groups vying for a limited fixed supply of suitable land. Lowland rice farmers rely on the periodic river floods to irrigate their fields and to deposit nutrients in the soil.

Agriculture in the region is not a monoculture system, sugar cane, taro, yams, sago palm, bananas and coconuts are also cultivated. The distribution of the crops is also subject to the same lowland and upland division as cultivation of seed crop. Banana and sago palm plantations are ubiquitous in the low lands, providing a useful compliant to the diets of the population in the advent of rice failures. Taro and yams provide a valuable source of food to upland farmer’s endemic as they are to the forests of the highlands. Sugar cane is maintained sporadically in only the largest groups or settlements, grown separately in small gardens it requires significant investment in terms of labour for even a slight return. Famers also maintain herds of swine and chickens, which they either drive from site to site or keep in pens of bramble or stone. Land animals themselves are not the only animals under the mastery of Sisisnc’s people. Some enterprising souls have taken to trapping fish in small channels or tributaries, feeding them and then draining or allowing the water to evaporate in the dry season. Salting is developing as a means of storing this perishable seasonal bounty, although only in areas with abundant salt.

Sailing in an inhabited archipelago should by the nature of its construction have a long history. Sisisnc is no exception; the coastal dwellers have long referred to themselves not in terms of terrestrial markers but in terms of their position to the sea. One does not say, ‘I live over those hills, and through the deep jungle’ one instead says ‘I live up the coast, past the deep water, and up the river’. Socially they also refer to themselves in maritime terms; they are a ‘boatload’ in number for instance. Social divisions are justified on the basis of which canoe their ancestors travelled on to reach their current abodes. Over time these successive narratives are being strung together, to rationalise the relationships between different islands and groups.

Sailing explains how agriculture and metallurgy spread. The sailors of the archipelago have no written language to record charts or rutters, they only had an oral tradition. What they pass down is the means of navigating not with maps or any other aids but by the swell and wave patterns, cloud formations, winds, birds and sea life. In this way it is possible to sail into the open ocean with no knowledge of what lies ahead and to know just when to turn the double rigger canoe to hit land, tipped off by a flight of birds, or a few strands of weed. For generations upon generations the population of islands would in a bold leap launch themselves across the ocean seeking new lands. Sometimes they would fall off the end of the world, more often than not they would come across islands as yet uncharted.

Metallurgical skill was also widespread, if somewhat geographically concentrated. Bronze, brass, copper, iron and tin are known and used in most islands even if the inhabitants themselves don’t necessarily how to produce them. Metals are yet to be applied to anything other than the generation of ritual and luxury items for which they are prized. Metal working is still a cottage industry. Small temporary forges are constructed in the highlands when occasionally a group strays over rich ores. It is the earliest significant trade item.

)?

)?