Broken_Erika

Play with me.

Canada's cities are losing up to 19 days of winter

Days above 0 C have seen dramatic increase around the world, Climate Central analysis finds

In just the past 10 years, cities around the world, including in Canada, have lost weeks' worth of winter ski, skate and snow days each year due to climate change. They've been replaced by dozens of days of rain, melt and mud, according to a new analysis by Climate Central, a climate research and communications non-profit.In Canada, some cities and regions that have lost more than two weeks of winter weather, including Vancouver (19 days), B.C.'s Greater Nanaimo region (18 days) and Ontario's Niagara region (15 days).

Toronto has lost 13 days, and even Montreal and Calgary — known for being cold — have lost six and five days below zero, respectively, per year.

Kristina Dahl, vice president for science at Climate Central, said these recent changes are very noticeable because snow turns to rain when the temperature rises above freezing at 0 C.

They may also be quite poignant because winter is a time for cozy holidays in many parts of the world, she added. "Those holidays are times that we remember as children and the traditions that come along with them," she said. "Seeing it warm is almost like losing some of the past."

Climate Central looked at the daily minimum temperatures in December, January and February in 901 cities and 123 countries around the world between 2014 and 2023.

It counted the change in the number of days above zero during that time period, a result of human-caused climate change driven mainly by the burning of fossil fuels.

Why some places lost so many winter days

More than a third of the countries analyzed lost at least a week's worth of winter days during the past decade. The hardest hit — Denmark, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — each lost at least three weeks (up to 23 days) of winter days.Dahl said there were two main reasons some countries and cities were affected more than others. Some, such as Europe (and Canada), are warming faster than the global average.

- What does winter have in store for Canadians this year?

- First Person

Canada is winter. With our warming climate, I feel like I'm losing a part of me

"So it doesn't take a whole lot of climate change to kick a bunch of winter days ... above that freezing threshold," Dahl added.

Robert McLeman, director of the RinkWatch project that is tracking outdoor skating rinks in Canada for the 14th season this year, said the biggest change has been in the onset of winter. He thinks the new Climate Central analysis is a "great way for Canadians to recognize that our climate is changing."

The report didn't break down what part of the winter the days were disappearing from. But McLeman, a Wilfrid Laurier University professor who has studied historical records of rink-building, said half a century ago, people were building rinks in Southern Ontario in early December, and ski hills would have plenty of snow to operate before Christmas holidays.

Today, in mid-December, he said, "I'm looking outside at green grass right now, outside my window in Waterloo, [Ont.]."

He added that local skating rinks no longer get started until the first or second week of January.

- Analysis

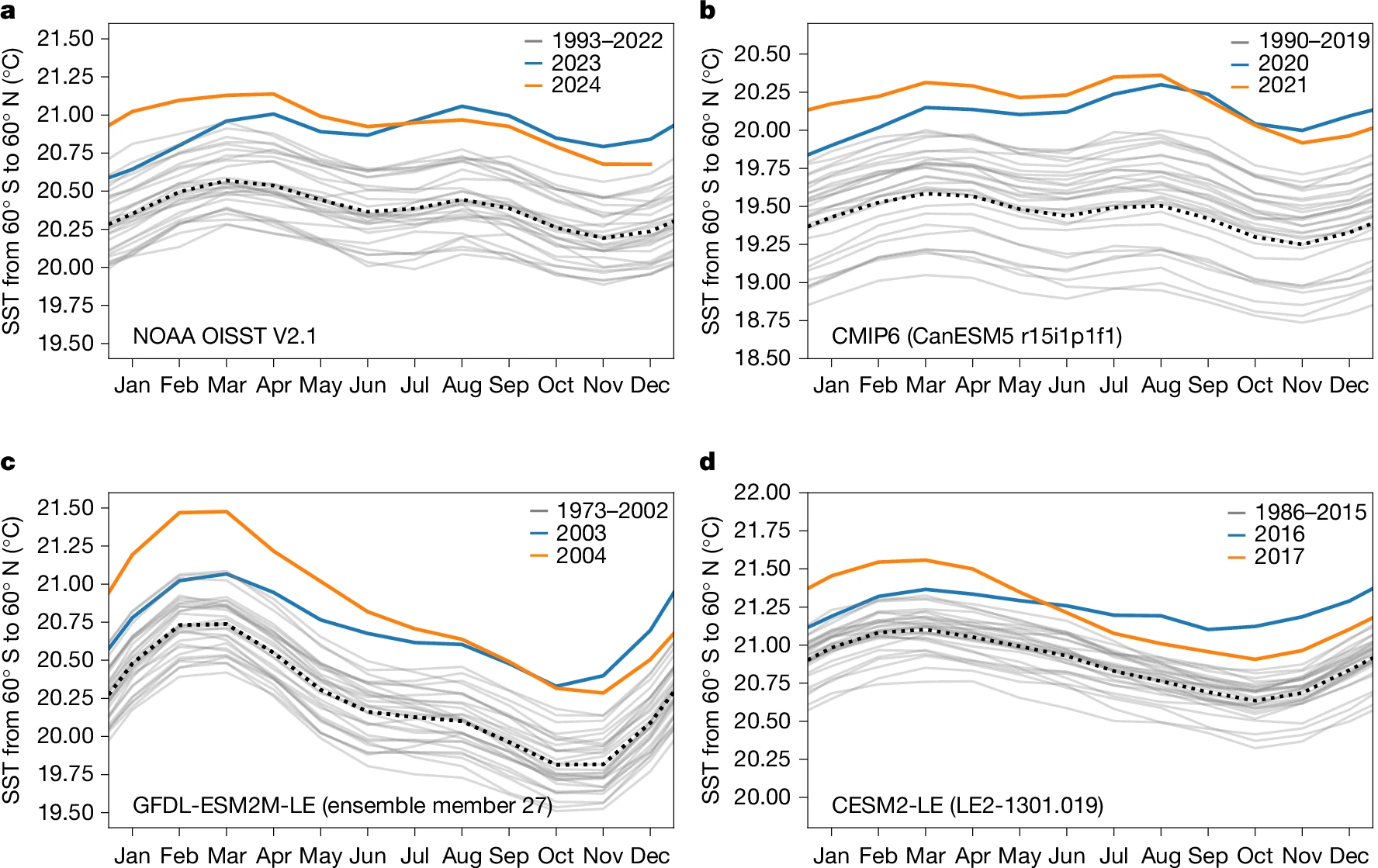

Why has Earth been so unusually hot for the past 2 years? Climate scientists are trying to figure that out - Climate change is bringing earlier springs, but it's wreaking havoc on animals

But aren't warmer winters kind of nice?

Dahl called the loss of cold winter days a "delight-mare.""It's nice to get a break from the freezing cold temperatures for us," she acknowledged. "But when you stop and think about why that's happening, it really does give you that sinking feeling — this is climate change happening."

And it can have many negative impacts, she added: It can cause water shortages in areas that rely on melting snow for both drinking and agriculture; allow the spread of disease-carrying pests such as ticks and mosquitoes into new areas; threaten populations of animals and plants; disrupt farming; and spoil winter recreation activities that are a part of our culture and economy, such as skating and skiing.

Sapna Sharma is a biology professor at York University who studies how ice is changing on lakes around the world.

She's found ice-free years become far more common for many lakes, leading to problems such as toxic algae blooms that follow in the summer.

But the freezing and thawing as the temperature dips above and below zero more often also weakens the ice.

"Weaker ice conditions contribute to more drownings," she said.

Connor Reeve is an ecologist postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University, who looked at the impact of winter and climate change on conservation of animals and plants during his recent PhD at Carleton University in Ottawa.

The lack of ice on the Rideau Canal during that time was a "real bummer," he recalled.

He said Climate Central's analysis "adds perspective to the changes the world is experiencing."

- Europe's cities are turning outdoor ice rinks into roller rinks. How will ours adapt?

- Second Opinion

Why insect-transmitted illnesses are emerging threats in Canada and beyond

While it will affect many human recreational activities such as fishing and hunting, warming winters affect many animals and plants in different ways, he said. For example, they cause less cold tolerant species to move north and push out those adapted to cooler temperatures or lead to a mismatch between co-dependent species that respond to the warming weather in different ways, such as flowers and pollinators.

Temperatures could respond quickly to emissions drop

Dahl said the trend toward warmer temperatures will continue as long as humans continue to burn fossil fuels. Some regions will have to adapt, for example, by finding new ways to manage water supplies through the year to compensate for lost snowpack in winter.But Dahl said the good news is that temperatures are expected to respond quite quickly once we stop emitting greenhouse gases.

"The latest science has us thinking that within about 10 years of reaching zero emissions, temperatures would would stop increasing," she said. "So, you know, even within our lifetimes we could see that change."

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/lost-winter-climate-central-1.7411756