You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Global warming strikes again...

- Thread starter CavLancer

- Start date

Lexicus

Deity

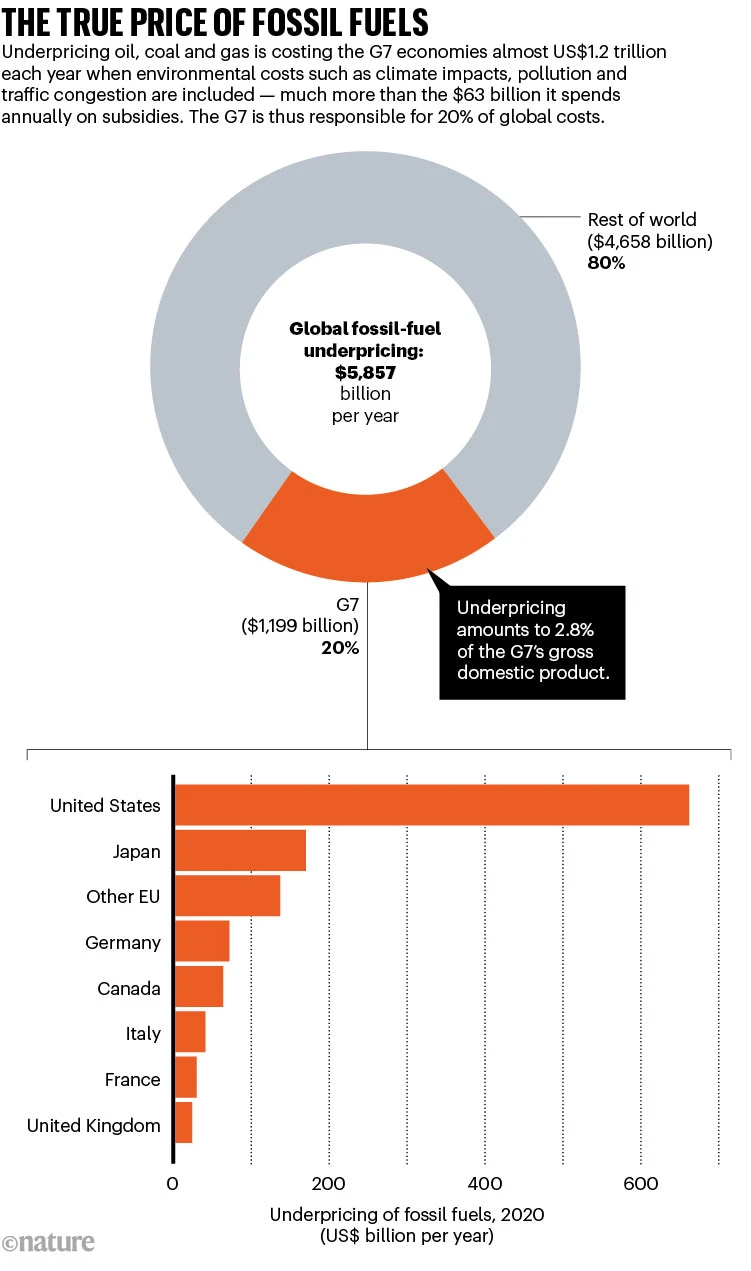

How does the "true" price compare to the market price? I suspect this study is underestimating the true price if they think the underpricing in the G7 economies only amounts to 2% of the G7's GDP.

This is the relevant paragraph from the article:How does the "true" price compare to the market price? I suspect this study is underestimating the true price if they think the underpricing in the G7 economies only amounts to 2% of the G7's GDP.

But at the same time, market distortions favouring fossil fuels remain 4. Across the G7 countries, subsidies — such as incentives for increased production, write-offs and tax deductions and reducing prices paid by consumers — for oil, coal and gas amount to $63 billion per year, or $62 per person, on average 5. Artificially depressed prices deter fast growth of low-carbon energy and have helped to spur a post-pandemic surge in fossil-fuel consumption and greenhouse-gas emissions 6. But the true cost is much greater. Adding in the environmental and health costs of fossil-fuel use, including climate impacts, pollution, traffic congestion and road accidents, as well as forgone tax revenues, underpricing fossil fuels is costing the G7 nations almost $1.2 trillion each year — 2.8% of the G7’s GDP and $1,186 per person 5. For the rest of the world, the cost is $4.7 trillion.

Reference 5 is:

Parry, I. W. H., Black, S. & Vernon, N. Still Not Getting Energy Prices Right: A Global and Country Update of Fossil Fuel Subsidies (International Monetary Fund, 2021).

So that is the IMF number, and it is from a book not a peer reviewed journal. I think some undercounting may be going on.

Judging this would require knowing what current final use expenditure on fossil fuels in those countries is to begin with. If it were 5% of their GDP, then that 2.7% of GDP in under-pricing would still represent a full third of the true value. Need to know the proportion of underspend.How does the "true" price compare to the market price? I suspect this study is underestimating the true price if they think the underpricing in the G7 economies only amounts to 2% of the G7's GDP.

Last edited:

Broken_Erika

Play with me.

What has climate finance paid for? Gelato shops, a coal plant and more

No rules exist about what counts as climate help to developed nations, and some projects may not help

Italy helped a retailer open chocolate and gelato stores across Asia. The United States offered a loan for a coastal hotel expansion in Haiti.Belgium backed the film La Tierra Roja, a love story set in the Argentine rainforest. And Japan is financing a new coal plant in Bangladesh and an airport expansion in Egypt.

These were some of the findings uncovered during a climate finance investigation by reporters from Reuters and Big Local News, a journalism program at Stanford University in California.

Funding for the five projects totalled $2.6 billion US ($3.5 billion), and all four countries counted their backing as so-called climate finance.

What is climate finance?

It includes grants, loans, bonds, equity investments and other contributions meant to help developing nations reduce emissions and adapt to a warming world.Developed nations have pledged to funnel a combined total of $100 billion US ($135 billion Cdn) a year toward this goal, which they affirmed during climate talks in Paris in 2015.

These countries reported more than 40,000 direct contributions toward the finance target, totalling more than $182 billion US ($246 billion), from 2015 to 2020, the last year for which data is available.

- The world is supposed to share the cost of fighting climate change. Here's how that works

- Developed world falls short of $100B commitment to help poorer countries fight climate change: report

What kind of spending counts as climate finance?

There are no official guidelines for what activities count. The UN Climate Change secretariat told Reuters it is up to the countries themselves to decide whether to impose uniform standards.Developed nations have resisted doing so.

Although a coal plant, a hotel, chocolate stores, a movie and an airport expansion don't seem like efforts to combat global warming, nothing prevented the governments that funded them from reporting them as such to the United Nations and counting them toward their giving total.

In doing so, they broke no rules.

Though some organizations have developed their own standards, the lack of a uniform system of accountability has allowed countries to make up their own.

"This is the wild, wild west of finance," said Mark Joven, Philippines Department of Finance undersecretary, who represents the country at UN climate talks. "Essentially, whatever they call climate finance is climate finance."

Why did Italy, Japan, the U.S. and Belgium think their projects counted as climate finance?

When asked, an Italian government official said Italy aims to consider climate in all of its financing, but did not elaborate on how the chocolate stores met that goal.A U.S. official said the Haiti hotel project counts because it includes storm water controls and hurricane protection measures.

A Belgian government spokesman defended counting the grant for the rainforest movie as climate finance because the film touches on deforestation, a driver of climate change.

Japanese officials consider the power and airport projects green because they include cleaner technology or sustainable features.

How did reporters investigate how the money was spent?

In an effort to understand how that money is being spent, reporters from Reuters and Big Local News examined thousands of records that countries submitted to the UN to document contributions.The system's lack of transparency made it impossible to tell how much money is going to efforts that truly help reduce global warming and its impacts.

Countries are not required to report project details. The descriptions they disclose are often vague or non-existent — so much so that in thousands of cases, they don't even identify the country where the money went.

"You cannot really follow the money, track the money, track the impact," said Romain Weikmans, a senior research fellow specializing in climate finance at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

What about Canada?

Some countries, such as the United Kingdom, Canada and the Netherlands, do submit detailed reports, and Reuters tallied tens of billions of dollars in spending from at least 33 countries that aligned with stated climate goals. That included investments in renewable energy and projects that build resilience to natural disasters.Is this greenwashing?

Decisions to claim borderline projects as climate finance often don't reflect a deliberate attempt to mislead, said Gaia Larsen, director of climate finance access at the World Resources Institute, a non-profit research organization that tracks climate finance.But when countries inflate their funding numbers with things like coal-fired power, she said, the result can resemble greenwashing — when companies make exaggerated or misleading claims about their environmental stewardship.

What do developing nations say about mislabelled climate financing?

Some officials from potential recipient countries say that, before more money starts to flow, clearer definitions of what qualifies as climate finance and more transparency in reporting contributions are needed.More than 100 times since 2012, developing nations or groups acting on their behalf have called for such improvements, according to a Reuters review of UN submissions, videos of climate meetings and climate negotiation bulletins.

"If we are telling ourselves we are spending money and investing in our future in a way that we are not, then we are courting disaster," said Matthew Samuda, a minister in Jamaica's Ministry of Economic Growth and Job Creation.

- What on Earth?

What a broken climate finance pledge means for developing countries - As countries and the private sector make climate pledges, this island nation fears for its future

Why do some developed countries oppose stricter rules about climate finance?

Climate negotiators from wealthy countries that oppose stricter rules told Reuters that more restrictions on how funds are spent could limit developing nations' autonomy in tackling climate change, restrict the flow of money and hinder the flexibility needed to keep pace with the fast-evolving crisis and the technologies needed to solve it.Gabriela Blatter, Switzerland's principal policy adviser for international environment finance, said developed nations aren't resisting a definition so they can claim "anything under the sun" as climate finance. Rather, she said, they want to stay true to the Paris Agreement, which aims to respect the right of each country to set its own course in fighting the effects of climate change.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/un-climate-finance-1.6861666

Lexicus

Deity

What has climate finance paid for? Gelato shops, a coal plant and more

No rules exist about what counts as climate help to developed nations, and some projects may not help

Italy helped a retailer open chocolate and gelato stores across Asia. The United States offered a loan for a coastal hotel expansion in Haiti.

Belgium backed the film La Tierra Roja, a love story set in the Argentine rainforest. And Japan is financing a new coal plant in Bangladesh and an airport expansion in Egypt.

These were some of the findings uncovered during a climate finance investigation by reporters from Reuters and Big Local News, a journalism program at Stanford University in California.

Funding for the five projects totalled $2.6 billion US ($3.5 billion), and all four countries counted their backing as so-called climate finance.

What is climate finance?

It includes grants, loans, bonds, equity investments and other contributions meant to help developing nations reduce emissions and adapt to a warming world.

Developed nations have pledged to funnel a combined total of $100 billion US ($135 billion Cdn) a year toward this goal, which they affirmed during climate talks in Paris in 2015.

These countries reported more than 40,000 direct contributions toward the finance target, totalling more than $182 billion US ($246 billion), from 2015 to 2020, the last year for which data is available.

- The world is supposed to share the cost of fighting climate change. Here's how that works

- Developed world falls short of $100B commitment to help poorer countries fight climate change: report

What kind of spending counts as climate finance?

There are no official guidelines for what activities count. The UN Climate Change secretariat told Reuters it is up to the countries themselves to decide whether to impose uniform standards.

Developed nations have resisted doing so.

Although a coal plant, a hotel, chocolate stores, a movie and an airport expansion don't seem like efforts to combat global warming, nothing prevented the governments that funded them from reporting them as such to the United Nations and counting them toward their giving total.

In doing so, they broke no rules.

Though some organizations have developed their own standards, the lack of a uniform system of accountability has allowed countries to make up their own.

"This is the wild, wild west of finance," said Mark Joven, Philippines Department of Finance undersecretary, who represents the country at UN climate talks. "Essentially, whatever they call climate finance is climate finance."

Why did Italy, Japan, the U.S. and Belgium think their projects counted as climate finance?

When asked, an Italian government official said Italy aims to consider climate in all of its financing, but did not elaborate on how the chocolate stores met that goal.

A U.S. official said the Haiti hotel project counts because it includes storm water controls and hurricane protection measures.

A Belgian government spokesman defended counting the grant for the rainforest movie as climate finance because the film touches on deforestation, a driver of climate change.

Japanese officials consider the power and airport projects green because they include cleaner technology or sustainable features.

How did reporters investigate how the money was spent?

In an effort to understand how that money is being spent, reporters from Reuters and Big Local News examined thousands of records that countries submitted to the UN to document contributions.

The system's lack of transparency made it impossible to tell how much money is going to efforts that truly help reduce global warming and its impacts.

Countries are not required to report project details. The descriptions they disclose are often vague or non-existent — so much so that in thousands of cases, they don't even identify the country where the money went.

"You cannot really follow the money, track the money, track the impact," said Romain Weikmans, a senior research fellow specializing in climate finance at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

What about Canada?

Some countries, such as the United Kingdom, Canada and the Netherlands, do submit detailed reports, and Reuters tallied tens of billions of dollars in spending from at least 33 countries that aligned with stated climate goals. That included investments in renewable energy and projects that build resilience to natural disasters.

Is this greenwashing?

Decisions to claim borderline projects as climate finance often don't reflect a deliberate attempt to mislead, said Gaia Larsen, director of climate finance access at the World Resources Institute, a non-profit research organization that tracks climate finance.

But when countries inflate their funding numbers with things like coal-fired power, she said, the result can resemble greenwashing — when companies make exaggerated or misleading claims about their environmental stewardship.

What do developing nations say about mislabelled climate financing?

Some officials from potential recipient countries say that, before more money starts to flow, clearer definitions of what qualifies as climate finance and more transparency in reporting contributions are needed.

More than 100 times since 2012, developing nations or groups acting on their behalf have called for such improvements, according to a Reuters review of UN submissions, videos of climate meetings and climate negotiation bulletins.

"If we are telling ourselves we are spending money and investing in our future in a way that we are not, then we are courting disaster," said Matthew Samuda, a minister in Jamaica's Ministry of Economic Growth and Job Creation.

- What on Earth?

What a broken climate finance pledge means for developing countries- As countries and the private sector make climate pledges, this island nation fears for its future

Why do some developed countries oppose stricter rules about climate finance?

Climate negotiators from wealthy countries that oppose stricter rules told Reuters that more restrictions on how funds are spent could limit developing nations' autonomy in tackling climate change, restrict the flow of money and hinder the flexibility needed to keep pace with the fast-evolving crisis and the technologies needed to solve it.

Gabriela Blatter, Switzerland's principal policy adviser for international environment finance, said developed nations aren't resisting a definition so they can claim "anything under the sun" as climate finance. Rather, she said, they want to stay true to the Paris Agreement, which aims to respect the right of each country to set its own course in fighting the effects of climate change.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/un-climate-finance-1.6861666

Market solutions to climate change are generally scams

Oceans are turning greener probably due to climate change

More than half of the world’s oceans have become greener in the past 20 years, probably because of global warming. The discovery, reported today in Nature1, is surprising because scientists thought they would need many more years of data before they could spot signs of climate change in the colour of the oceans.

“We are affecting the ecosystem in a way that we haven’t seen before,” says lead author B. B. Cael, an ocean and climate scientist at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, UK.

The ocean can change colour for many reasons, such as when nutrients well up from its depths and feed enormous blooms of phytoplankton, which contain the green pigment chlorophyll. By studying the wavelengths of sunlight reflected off the ocean’s surface, scientists can estimate how much chlorophyll there is and thus how many living organisms such as phytoplankton and algae are present. In theory, biological productivity should change as ocean waters become warmer with climate change.

But the amount of chlorophyll in surface waters can vary markedly from year to year, making it hard to differentiate any changes induced by climate change from the big natural swings. Scientists thought it might take up to 40 years of observations to spot any trends2.

Another complicating factor is that numerous satellites have measured ocean colour over time, and each did so in a slightly different way, so the data cannot be combined. Cael’s team decided to analyse data from MODIS, a sensor aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite, which was launched in 2002 and is still orbiting Earth, far surpassing its anticipated six-year lifetime. The researchers looked for trends in seven different wavelengths of light from the ocean, rather than sticking with the single wavelength used to track chlorophyll. “I’ve thought for a long time that we could do better by looking at the full colour spectrum,” Cael says.

With two decades of MODIS data, the scientists were able to see long-term changes in ocean colour. They observed notable shifts in 56% of the world’s ocean surface, mostly in the waters between the latitudes of 40º S and 40º N. These tropical and subtropical waters generally don’t vary much in colour throughout the year, because the regions don’t experience extreme seasons — and so small long-term changes are more apparent there, Cael says.

The intensity of the colour change depends on the wavelength of light measured. In general, the waters are becoming greener over time.

To see if the shifts could be linked to climate change, the researchers compared the observations to the results of a model3 that simulated how marine ecosystems might respond to increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The observed changes matched those in the model.

Shades of green

Now, the question is what is turning the oceans greener. It’s probably not a direct effect of increasing sea surface temperatures, Cael says, because the areas where colour change was observed do not match up with those where temperatures have generally risen. One possibility is that the shift might have something to do with how nutrients are distributed in the ocean. As surface waters warm, the upper layers of the ocean become more stratified, making it harder for nutrients to rise to the surface. When there are fewer nutrients, smaller phytoplankton are better at surviving than larger ones, and so changes in nutrient levels could lead to changes in the ecosystem that are reflected in changes in the water's overall colour.

But this is just one idea; the researchers can’t yet say exactly why the changes are happening. “The reason we care about the colour is because the colour tells us something about what’s happening in the ecosystem,” Cael says.

The discovery ramps up expectations for the next big mission to monitor ocean colour — NASA’s Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite. Set to launch in January 2024, PACE will measure ocean colour in many more wavelengths than any previous satellite, a capability known as being ‘hyperspectral’.

“All of this definitely confirms the need for global hyperspectral missions such as PACE,” says Ivona Cetinić, an oceanographer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who works on PACE. The spacecraft “should allow us to understand the ecological implications of the observed trends in ocean ecosystem structure in years to come”.

Writeup Paper

More than half of the world’s oceans have become greener in the past 20 years, probably because of global warming. The discovery, reported today in Nature1, is surprising because scientists thought they would need many more years of data before they could spot signs of climate change in the colour of the oceans.

“We are affecting the ecosystem in a way that we haven’t seen before,” says lead author B. B. Cael, an ocean and climate scientist at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, UK.

The ocean can change colour for many reasons, such as when nutrients well up from its depths and feed enormous blooms of phytoplankton, which contain the green pigment chlorophyll. By studying the wavelengths of sunlight reflected off the ocean’s surface, scientists can estimate how much chlorophyll there is and thus how many living organisms such as phytoplankton and algae are present. In theory, biological productivity should change as ocean waters become warmer with climate change.

But the amount of chlorophyll in surface waters can vary markedly from year to year, making it hard to differentiate any changes induced by climate change from the big natural swings. Scientists thought it might take up to 40 years of observations to spot any trends2.

Another complicating factor is that numerous satellites have measured ocean colour over time, and each did so in a slightly different way, so the data cannot be combined. Cael’s team decided to analyse data from MODIS, a sensor aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite, which was launched in 2002 and is still orbiting Earth, far surpassing its anticipated six-year lifetime. The researchers looked for trends in seven different wavelengths of light from the ocean, rather than sticking with the single wavelength used to track chlorophyll. “I’ve thought for a long time that we could do better by looking at the full colour spectrum,” Cael says.

With two decades of MODIS data, the scientists were able to see long-term changes in ocean colour. They observed notable shifts in 56% of the world’s ocean surface, mostly in the waters between the latitudes of 40º S and 40º N. These tropical and subtropical waters generally don’t vary much in colour throughout the year, because the regions don’t experience extreme seasons — and so small long-term changes are more apparent there, Cael says.

The intensity of the colour change depends on the wavelength of light measured. In general, the waters are becoming greener over time.

To see if the shifts could be linked to climate change, the researchers compared the observations to the results of a model3 that simulated how marine ecosystems might respond to increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The observed changes matched those in the model.

Shades of green

Now, the question is what is turning the oceans greener. It’s probably not a direct effect of increasing sea surface temperatures, Cael says, because the areas where colour change was observed do not match up with those where temperatures have generally risen. One possibility is that the shift might have something to do with how nutrients are distributed in the ocean. As surface waters warm, the upper layers of the ocean become more stratified, making it harder for nutrients to rise to the surface. When there are fewer nutrients, smaller phytoplankton are better at surviving than larger ones, and so changes in nutrient levels could lead to changes in the ecosystem that are reflected in changes in the water's overall colour.

But this is just one idea; the researchers can’t yet say exactly why the changes are happening. “The reason we care about the colour is because the colour tells us something about what’s happening in the ecosystem,” Cael says.

The discovery ramps up expectations for the next big mission to monitor ocean colour — NASA’s Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite. Set to launch in January 2024, PACE will measure ocean colour in many more wavelengths than any previous satellite, a capability known as being ‘hyperspectral’.

“All of this definitely confirms the need for global hyperspectral missions such as PACE,” says Ivona Cetinić, an oceanographer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who works on PACE. The spacecraft “should allow us to understand the ecological implications of the observed trends in ocean ecosystem structure in years to come”.

Writeup Paper

Spoiler Legend :

Fig. 2 | The modelled R rs ToE of 20 years or less is similar to the location and extent of the observed 20-year data where SNR is higher than 2. a, Cumulative distribution function of the ToE of the ocean-colour trend in the model simulation. The orange point indicates the fraction of the total surface-ocean area with a significant trend in the 20-year MODIS-Aqua time series. Compare this with Fig. 10 in ref. 2, which shows less than 10% of the ocean with an emerged Chl trend after 20 years. b, Map of the ToE in the model simulation (median = 22 years). Grid cells are coloured by percentile, with white at 20 years, such that all white and red grid cells have a ToE of 20 years or less, and all blue grid cells have a ToE of more than 20 years. Grey grid cells do not have significant Rrs trends over the twenty-first century. See ref. 2 for a similar plot for Chl.

Even language is now adapting to account for climate change.

"For deaf children, teachers and scientists, talking about things like "greenhouse gases" or "carbon footprint" used to mean spelling out long, complex scientific terms, letter by letter. Now they are among 200 environmental science terms that have their own new official signs in British Sign Language (BSL). The deaf scientists and sign language experts behind the update hope the new vocabulary will make it possible for deaf people to fully participate in discussions about climate change, whether it's in the science lab or classroom."

(Follow the link for the rest of the article and a short video.)

"For deaf children, teachers and scientists, talking about things like "greenhouse gases" or "carbon footprint" used to mean spelling out long, complex scientific terms, letter by letter. Now they are among 200 environmental science terms that have their own new official signs in British Sign Language (BSL). The deaf scientists and sign language experts behind the update hope the new vocabulary will make it possible for deaf people to fully participate in discussions about climate change, whether it's in the science lab or classroom."

(Follow the link for the rest of the article and a short video.)

Last month was the world's warmest February in modern times, the EU's climate service says, extending the run of monthly records to nine in a row.

Synobun

Deity

- Joined

- Nov 19, 2006

- Messages

- 24,592

Well done, everyone! Let's make it ten!Last month was the world's warmest February in modern times, the EU's climate service says, extending the run of monthly records to nine in a row.

Akka

Moody old mage.

We got a grand total of less than ten days where there were any snow in the garden this year.

Meanwhile, the old people in the village speak of how they would have entire monthes of snow-covered scenery when they were young.

I guess we didn't move at a high enough altitude when moving in, can't catch up.

Meanwhile, the old people in the village speak of how they would have entire monthes of snow-covered scenery when they were young.

I guess we didn't move at a high enough altitude when moving in, can't catch up.

I remember entire months of snow-covered scenery, from the '60s and '70s. It was in the mid-'80s that winters started routinely getting weird.We got a grand total of less than ten days where there were any snow in the garden this year.

Meanwhile, the old people in the village speak of how they would have entire monthes of snow-covered scenery when they were young.

I guess we didn't move at a high enough altitude when moving in, can't catch up.

Altitude does matter, though. Some years they get an early snowfall in August in the mountains.

Lexicus

Deity

stfoskey12

Emperor of Foskania

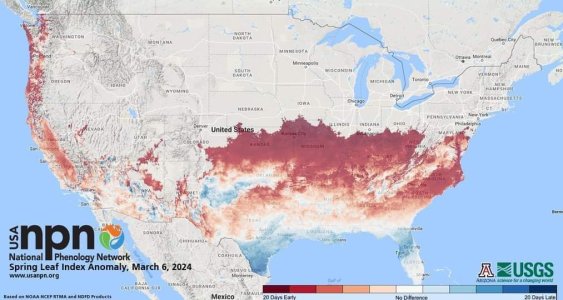

I've been casually checking that index since 2016, and it seems like most years a good portion of the country is 2-3 weeks early.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 328

- Views

- 16K

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 24

- Views

- 1K