Epilogue

January 1, 1912

Paris, France

After five long, brutal years, the Armistice was signed in a railway carriage in the Forest of Compiègne in northern France. Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France signed the armistice on behalf of Le Entente Grande, German Chancellor Matthias Erzberger signed on behalf of the Conference of Nations. At the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1911, the greatest war in the history of humanity came to an end.

Signing the Armistice

The Great War claimed over ten million lives. Every family lost someone. They were young soldiers sacrificed by the vain-glorious empires on battlefields as diverse as the jungles of Mozambique to the frigid mountains of Norway. They rest under the Atlantic in the twisted remains of sunken ships, in the mud of the Russian marshes, and among the smoking ruins of Seoul. But the war also claimed countless civilian victims; men, women and children who were killed in a new kind of war – total war. This was a war without precedent; a war without boundaries, a war in which the entire resources of nations are pitted against each other, and a war in which the distinction between military and civilian, between the bloody horrors of the battlefield and the relative safety of home, had fade away.

The UNA and the Alliance of the Three Kingdoms conspired to bring down the global Franco-Swazi hegemony. Even though the Conference forces together vastly outnumbered what the Entente could muster, the Conference failed to break the Entente in the first year of the war, and so the war dragged on. In the end, the Conference gave up. Some commentators cited the Entente’s excellent spy network for its success; others believed the Entente members’ close cooperation was key to their triumph. Certainly the large, unwieldy, ramshackle Conference of Nations never evolved into a close-knit alliance.

The euphoria of armistice was soon replaced by a feeling of exhaustion and sorrow at the absurdity of it all. It should have been the best of times. Science and technology were supposed to bring deliverance for the common man. People had never lived better, or longer, than at the dawn of the twentieth century. But progress also produced the machine gun, the artillery, the explosives, and the poison gas. Technology brought the world closer together. It also led some to believe that they could own it.

At the time of the armistice, Germany was one of the few countries in the UNA which remained at war; most either collapsed or negotiated a ceasefire. The German military junta capitalized on the French failure to invade Scandinavia to retake Berlin with assistance from UNA allies. However, by this time the country was in ruins and exhausted to breaking point. Faced with imminent defeat, the supreme commander of the Reichswehr decided to take this moment to settle old scores, and purged the communists, who were massacred in the hundreds of thousands. As expected, the frontline collapsed. The military relinquished power to a civilian government, who was left with the unenviable task of negotiating the Armistice. Chancellor Erzberger, who had only been in office for two months when the Armistice was signed, was assassinated on his return to Berlin. Germany descended into short, savage civil war, which ended, violently, with the arrival of the French occupation forces.

French troops occupy Köln

Soviet Russia had resorted to scorched earth tactic in its struggle against the Accord, but it barely delayed the communist state’s destruction. The Caliphate installed its protégé, the Tatar rebel leader Serik Nassar, as Sultan of Russia. The new ruler inherited a wasteland and a people left destitute by decades of war and deprivation.

Famine stricken children in Ukraine

The four North American UNA powers, the CSA, Texas, California and Librulstan, lost millions of men in their attempt to bring down France and Swaziland. With the exception of Chile, their homelands were spared foreign occupation, but the human and economic cost of the war was too high for them to bear. Librulstan and California both experienced revolutions, their governments brought down by angry and disillusioned citizens. Mexico, Alaska and Hawaii immediately declared their independence, though at the moment it is unclear what form they will take, and whether the Entente would even allow their independence. The Australian Republic also collapsed, and though its revolution was more peaceful than most, in some cities it took the arrival of Swazi and Medinan peacekeeping forces to restore order. In Java, an Indonesian independence movement has been gaining strength, setting the scene for a potential clash with the Caliphate, who has claims in the East Indies based on the Caliph’s authority as protector of all Muslims.

The flag of independent Indonesia is raised at Batavia

The People’s Republic of Gran Colombia remained a redoubt of communism, though under the Armistice terms Swaziland has stationed troops in Guiana. With the UNA effectively rendered irrelevant, the PRGC has lost the protection which has shielded it from the Accord’s anti-communism crusade for so long. With the 250,000 Entente troops stationed on its borders ready to pounce, survival is the Colombian leadership’s all-consuming preoccupation. While diplomats shuttle between Paris and Bogota to secure recognition from the Entente, back home the military is preparing for the worst. The aged León de Otilla, who is now so infirm that he could barely stand, defiantly proclaimed that Colombia would fight foreign occupation to the death. It’s unclear whether the country would fight with him.

Villagers in rural Colombia, facing an uncertain future, gathers to hear the local party cadre speak

The Three Kingdoms are no more. The first to fall was Siam, at one time a trusted Accord member. The King must have seen the fall coming; he had betrayed his allies, lied to his people, and sent millions to their deaths. It was all against Buddha’s teachings, and his karma is bound to catch up with him sooner or later. Sure enough, after yet another failed offensive, the Royal Siamese Army mutinied. Swazi and French agents had been active in spreading discontent in the provinces and among ethnic minorities, and soon they revolted too. The fall, when it came, was rapid but somewhat anti-climatic. Bangkok surrendered unopposed and the King fled into exile in Hawaii.

Indians throw out the Siamese

Xi’an was next. The Dragon King was central to the conspiracy, but now his grand operation is falling down like a house of cards. Enemies invade the Kingdom from all directions. Ashamed and dispirited, the King abdicated and then, depending on who you believe, either committed suicide or retreated quietly into a monastery. The Southern Han continued to resist after its allies had collapsed, initially refusing to agree to the Armistice. The imperial ministers, however, had had enough, and threw the Emperor off his throne. China was partitioned between France in the north and Swaziland in the south, though the arrangement has yet to be finalized.

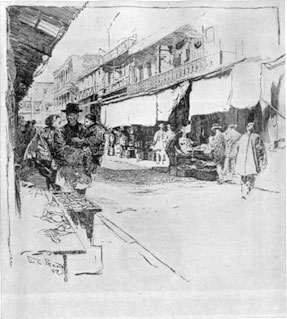

Execution of a captured bandit in Shanghai. Crime is rife in post-war China

Le Entente Grande emerged from the war supreme, but exhausted. Medina, France and Swaziland has weathered by far the most serious threat to their global dominance, and survived. But the cost was high; millions dead, and large areas of their countries, and the countries that they have conquered, in ruins.

France is now in control of all of Western and Central Europe, except for the British Isles, which it agreed to transfer to Canada, and neutral Switzerland. But although they have won the war, they now face trouble keeping the peace. The economy is in tatters, rationing is still in effect, and they still face armed insurgencies in Poland, Hungary and parts of Germany and Scandinavia. Many remain hopeful that a new European Republic can emerge out of the ruins.

Ruins of a town in Spain

Greece joined the war on the right side in time. For their troubles, the Greeks have been rewarded with a protectorate over Korea and Ceylon. Turkey technically fought on the side of the Conference, though their soldiers haven’t seen much action. Its leaders are trying their best to persuade the Entente that it should not suffer the same fate as its ally Libya, which had been annexed by the Swazis. Both Greece and Turkey face a challenge from a new revanchist Bosnia.

The Caliphate’s dream of an empire embracing all Muslims seems close to reality. Medinan forces are being invited into India to keep the peace, and its allies in the Entente have agreed to give the Caliph a free hand over Indonesia and Turkey. Spanish Yakutia fought on the Entente’s side against the Soviet Union and preserves its independence, though its requests for the return of Iberia still fall on deaf ears.

Swaziland remained the world’s single most powerful state. It retained its dominance in Africa, and has sent its famous warriors to South America, Asia and Australia to occupy its spoils of war. But as in France, the cost of victory is enormous.

The slain on the battlefield of Mozambique

Canada was the only country to remain strictly neutral in the war. Its leaders attempted to get the belligerents to negotiate, to no avail. During the conflict it accepted millions of refugees, including many draft dodgers from its neighbours to the south, oversaw the operations of the Red Star humanitarian organization, and delivered famine aid to millions in the war zones.

A Canadian supply relief ship, bound for Spain

Xi’an, Occupied China

The French Vice-President, the Medinan viceroy and the Swazi Crown Price, standing in for their respective heads of state, celebrated the New Year together with their advisors and generals at the Imperial Palace in Xi’an. The Entente flags flew in triumph from the city walls. Fireworks lit up the sky.

Will there finally be peace, or is this merely a false dawn?

The future is now theirs to shape.