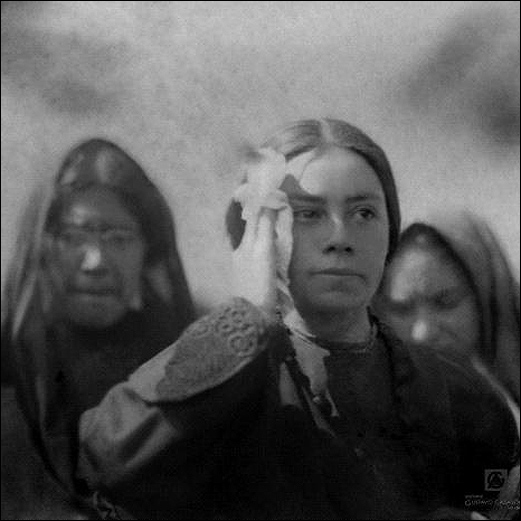

1920-1926: A "Woman's" Era

Though President Bernal had made it clear that she would be far less "traditionally" revolutionary than the cowboy Pancho Villa, progress would still be key to her leadership. This meant that research spending, which had been sinking lower and lower over the years, received a slight boost after Bernal's rise to power.

Progress was also made in appointments, which, like the office of the President itself, had been held exclusively by men until this point. Bernal appointed Juana Belen Gutierrez de Mendoza, a noted feminist, to the Supreme Court all the way from a municipal position she had never escaped due to her gender. Between this and the creation of a new Minister of Women's Issues title, Bernal quickly showed that she looked to empower every woman in Mexico, not just herself.

The still plentiful government funds soon found a use as well; President Bernal proved she was as not as hesitant to spend money on social works as the other members of her party. Many more universities and libraries received extended funding under the new Bernal Education Act, which included a note that any facility looking for such funding must prove itself to be equal-opportunity for both men and women, though such restrictions were only mildly enforced by disinterested bureaucrats.

Like her party members, however, the President was more than happy to expand the global free trade network, signing open borders agreements with the underdeveloped Republic of Ethiopia as an early foothold into the untapped wealth of central Africa.

The Middle East also received Mexican attention. Iran, a crumbling empire filled with outraged revolutionaries, requested Mexican oversight in establishing a new regime and protecting their interests from Soviet and Ottoman aggression, in exchange for near-exclusivity in access to the nation's natural resources. Aware of the region's oil fields, President Bernal happily agreed, continuing to establish Mexican dominance over the valuable black gold. Mexican Petroleum, commonly referred to as MP, was soon established as a government-owned corporation to manage the wells and newly-constructed railways within Iran.

In 1922, the Arango family from Guatemala moved to Mexico City and opened their own small, unassuming general store. Over the next few decades, that shop would grow into a department store and soon a nation-wide chain, bringing cheap goods to the whole country and making the Arangos wealthier than any other Mexican family, as well as cultivating a strong relationship with Christiano Felix.

Since the end of the Third Mexican-American War, use of balloon-like airships for reconnaissance had become common practice for the Mexican military. It was one of these zeppelins, on a typical recon flight over the largely unsettled Pacific Northwest, that noticed American railworkers deep in the Rocky Mountains. A second expedition soon caught site of their new settlement in the far north of Alaska, established to contest Mexico's dominance over both the Pacific Northwest and the world's access to oil.

Under Bernal, the state of Mexico's environment received some urgently needed care, as New Orleans completed the nation's first protected national park deep in the Mississippi wetlands, which hoped to educate and excite Mexicans when it came to the nation's natural wealth.

On the more conservative end of politics, Mexican espionage continued to rise, though Bernal would admit later that its spread had little to do with her influence. The continued increase in the use of telecommunications such as the telegraph had allowed the N.I.B. to develop more effective information networks and spy rings across the globe, giving Mexico a stronger advantage along with a clear picture of their rivals' activities.

Bernal's focus on progress extended to the development of Mexican industry. Factory districts sprung up in every major city, with coal plants powering the new electrical networks. Crowded slums began to spring up in places like the capital and Santa Fe as farmers flocked to the city for the high wages industry work provided, many of them abandoning land that had been given to them by President Villa due to the high amount of effort they needed to maintain them, sacrificing their "dreams of freedom" for convenience. The new slums lacked the infrastructure to accommodate the needs of their residents, and disease found itself rising to levels not seen since the nineteenth century.

By 1924, to deal with the new urban population crisis, Bernal appointed a young architect named Mario Pini as Chief of Urban Development in Mexico City to help develop infrastructure and resolve the issues. Pini would hold the position for many years, working on various projects.

The Colombians continued to aggressively expand through South America, attacking Brazil and launching a war to involve the entire continent. Mexicans were horrified at the attack on a close friend, but few had forgotten the last war, and the recovering nation was hesitant to provide any direct assistance.

President Bernal's focus on education and universities quickly paid off as major medical breakthroughs were accomplished. New understandings of disease, germs and the way they spread, alongside other safe practices, helped curb the pestilence in industrial slums. Government funded hospitals soon sprung up in cities like Los Angeles, Santa Fe and Mexico City, giving the poor somewhere to go besides pricy, private doctors.

Proud of her successes, President Bernal once again announced an increase in research spending for the 1926 budget.

The rush of new doctors soon found more humanitarian work in Vietnam, who had been grappling with disease ever since their independence. Volunteer trips to help the "poor, uneducated people" of the nation soon became a popular activity for youth hoping to see the world.

Mexico soon found itself to not be the only nation relinquishing their control of former territories. In Indonesia, rebellious fervor against their Dutch overseers had been slowly bubbling, now encouraged by funding from the Philippines. In 1926, a massive Muslim uprising forced the Dutch to accept Indonesian independence, creating yet another new major power in Southeast Asia.

The Philippines, however, seemed to have grown tired of completely independent rule. Though Pio del Pilar had been a staunch nationalist, his death in 1917 had been followed with several Presidents who had not empowered the nation as much as some had hoped. The latest leader of the islands, Augusto Martin, saw the benefit closer oversight with Mexico had once wrought. Though agreeing to remain autonomous and distinct, President Martin signed a deal with President Bernal that made the Philippines a satellite of Mexico, similar to the Mali, Iranian, Peruvian and Chinese Republics. The Mexican President herself had agreed due the people of the Philippines themselves accepting the decision, rather than having it thrust upon them.

Urban development continued rapidly as medical developments rushed to keep up with it. A 1926 census recorded 51,234,156 Mexican citizens, an astounding number that few nations could match.

By the end of 1926, Mexico still stood strong. Though their Golden Age of economic growth had slowed to a standstill, President Bernal's leadership had continued to push Mexico to top the world, rivaled only in influence by the Russian Empire.

But it could be the far left is tired of playing second fiddle...

But it could be the far left is tired of playing second fiddle...But it could be the far left is tired of playing second fiddle...