The U.S. Federal Reserve was founded 99 years ago, as a bulwark to the banking system and an antidote to its frequent runs and panics. Strictly speaking, it was Americas third attempt at a central bank. The first, organized by Congress in 1791, was allowed to expire after 20 years, leaving the young republic with only a patchwork system of weaker state banks. During the War of 1812, Congress realized its error (in the absence of a central bank, inflation had run rampant), and in 1816, it chartered a second bank, again for 20 years. The Second Bank of the United States was, in the main, a success. Its notes were circulated as currency, and it astutely managed their supply so as to keep the economy humming. Alas, President Andrew Jackson, a fierce opponent of both paper money and national banks, campaigned in 1832 against renewal of the charter, and indirectly against the banks brilliant but impetuous head, Nicholas Biddle. Resentment against financiers was running high, and the election became a referendum on the genteel Philadelphia banker versus the rough-hewn war heroand a referendum on the bank itself. Jackson won, and the Second Bank was, per his promise, destroyed. The U.S. economy promptly plunged into a severe depression. Biddle died not long after, in semi-disgrace, but the battle between bankers and populists never went away.

...

He studied the Depression as a graduate student at MIT, and as a young academic earned his reputation by expanding on Milton Friedmans classic monetary history. According to Friedman, the Feds failure in the 1930s was a matter of not printing enough money. Bernanke deduced that the real failure was letting the banking system implode. What Bernanke discovered was that it wasnt the quantity of money, it was that the banks stopped lending, says Stanley Fischer, formerly Bernankes thesis adviser at MIT and currently the governor of the Bank of Israel. More than the decline in money, it was the collapse of credit. The implication was that regulating banks in good timesand, if need be, rescuing them in badwas of prime importance, something Bernanke would remember in the 200709 crisis.

...

The particular problem of the 30s was deflation: goods were worth less each yearor, alternatively, dollars were worth more. In a mirror image of inflation, no one would spend, because lower prices were forever just around the corner, and no one would borrow, because they would have to repay their debts with more valuable currency. The central bank cut interest rates to try to induce borrowing and spending, but then it was bereft of tried-and-true methods of stimulating the economy. Production and employment kept spiraling downward; Keynes called this a liquidity trap.

...

But while Bernanke recognized the danger in theory, he did not anticipate the looming crash in home prices. Indeed, he argued that central banks, including the Fed, had tamed the extremes of the economic cycle. In 2005, in a speech in St. Louis, he cogently explained how capital from China and other countries was flowing into the U.S. mortgage market and spurring higher prices in residential real estate. He did not express concern. The following year, as the housing bubble reached its peak, he became Fed chairman.

n 2007, as the subprime-mortgage crisis leached into the financial markets, Bernankes training failed him. As a scholar, he had studied how bank failures worsened the Depression; as the Fed chair, he didnt scrutinize the banks closely enoughthat is, he overlooked the fact that dicey mortgage-backed securities made up a sizable portion of the assets of the biggest banks. Risk was concentrated in key financial intermediaries, he told me. It led to panics and runs. Thats what made it all so bad. Speaking of government officials collectively, he added, Everyone failed to appreciate that our sophisticated, hypermodern, highly hedged, derivatives-based financial systemhow ultimately fragile it really was.

There was, I think, another reason for his blindness: Bernanke had an academics faith in the markets essential rightness. He was so skeptical of the notion of mass-market folly that in his scholarly writings, he referred to bubbles in quotation marks. He was not, like Greenspan, ideologically opposed to government intervention, but he was dubious that anyone could identify, in real time, when markets were off course.

These criticisms aside, if one is assigning blame, it is important to note that the bubble inflated almost entirely on Greenspans watch. The time to avoid a crash was when mortgages were getting written, or when banks could still sell off assets without sparking a panic; by the time Bernanke arrived, a crisis was probably inevitable. In any case, by 2008, Bernanke was confronting the very type of banking meltdown he had spent his academic life studying. No one was better suited to the job; indeed, the Fed adopted the remedies Bernanke had outlined in his 2002 address nearly point for point.

...

Even rightward-leaning economists mostly give Bernanke a pass on his actions during the financial panic itself. The fog of war was pretty intense, and he avoided losing taxpayer money. But in the second stageresurrecting the economy, and potentially tinkering with the inflation ratehe has taken heat from thinkers on both sides of the aisle. Even the Feds Open Market Committee, the group that sets interest-rate policy, is splintered. In the Greenspan era, especially as the chairmans aura grew, this body spoke with one voice, rubber-stamping whatever the chairman wanted. Bernankes committee is a monetary Babelpartly because he is open to hearing contrary opinions, and partly because opinion is so deeply divided. While Greenspan withstood a dissenting vote here or there, Bernanke has suffered 32 nay votes, including three dissents in a single meeting. That hadnt happened in 20 years.

...

The formative experience for the European Central Bank was the hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s, which ever since has steeled central bankers on the Continent against the perils of printing money. In Frankfurt, the idea of lender of last resort wasnt, and isnt, embraced. For the U.S. Federal Reserve, the formative experience was a series of depressions beginning in the 19th century and culminating in the Great Depression. After the demise of Biddles bank in the 1830s, money in the U.S. consisted of whatever notes banks printed and people agreed to take. Even after the Civil War, when money became more uniform, currency was often a scarce commodity, and banking panics were frequent.

Even rightward-leaning economists mostly give Bernanke a pass on his actions during the financial panic itself. The fog of war was pretty intense, and he avoided losing taxpayer money. But in the second stageresurrecting the economy, and potentially tinkering with the inflation ratehe has taken heat from thinkers on both sides of the aisle. Even the Feds Open Market Committee, the group that sets interest-rate policy, is splintered. In the Greenspan era, especially as the chairmans aura grew, this body spoke with one voice, rubber-stamping whatever the chairman wanted. Bernankes committee is a monetary Babelpartly because he is open to hearing contrary opinions, and partly because opinion is so deeply divided. While Greenspan withstood a dissenting vote here or there, Bernanke has suffered 32 nay votes, including three dissents in a single meeting. That hadnt happened in 20 years.

Most of Bernankes dissenters are hawks, but Charles Evans, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, has dissented twice because he thinks the Fed should be willing to tolerate a higher rate of inflation until the job market recovers. Janet Yellen, the Feds vice chair, and William Dudley, president of the New York Fed, also lean toward increased stimulus. No previous Fed chief had to deal with such an internal crossfire.

Bernankes quandary derives from the fact, unusual among the worlds central banks, that the Fed has a dual mandateby law, it is required to promote maximum employment and also stable prices. The European Central Bank, by contrast, is supposed to worry only about inflation. This is why the latter twice raised interest rates in 2011, when Europe was teetering at the edge of recession and possibly default.

The formative experience for the European Central Bank was the hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s, which ever since has steeled central bankers on the Continent against the perils of printing money. In Frankfurt, the idea of lender of last resort wasnt, and isnt, embraced. For the U.S. Federal Reserve, the formative experience was a series of depressions beginning in the 19th century and culminating in the Great Depression. After the demise of Biddles bank in the 1830s, money in the U.S. consisted of whatever notes banks printed and people agreed to take. Even after the Civil War, when money became more uniform, currency was often a scarce commodity, and banking panics were frequent.

The Fed was conceived, in 1913, as a backstop to the financial system. Printing moneythe accusation that Rick Perry leveled against Bernankewas part of the job description from the outset. Currency still consisted of banknotes, only now the bank was the Federal Reserve. The Fed seemed to fulfill its promise during World War I, pumping hundreds of millions of emergency dollars into the financial system. During the Depression, for reasons that are still being debated, it failed. Bernanke clearly has avoided the worst mistakes central banks made in the Depression. Yet unemployment remains high, raising questions from some economists, especially on the left, as to whether the Fed has done enough.

...

Bernanke has given serious thought to the Krugman-Rogoff argument. One obstacle is practical. Fed policy works, in part, by getting the market to do the Feds work (if the Fed is buying bonds, traders who want to be on the same side of the markets as the central bank will buy bonds too). But any policy adopted by less than a 7-to-3 majority by the Feds Open Market Committee would not be viewed by markets as a credible policy, likely to endure, and Bernanke is not guaranteed to get this margin today. No central banker would do it, Mankiw says of raising the inflation target; the political reaction would be too severe. (When Mankiw, a Harvard economist, wrote a column raising the possibility of a higher inflation target, Drew Faust, the universitys president, received letters urging her to fire him.)

...

Still, the Fed has always faced the challenge of tightening credit after a period of ease. The fact that it has been accumulating long-term bonds rather than short-term bills is a relatively benign innovation, less exotic than many observers have claimed. So far, the hawks have seen inflation around every corner. So far, they have been wrong, and Bernanke has been right. The reasons critics so hate quantitative easing, I think, have less to do with the mechanics of bank reserves and more with nostalgia for a more cautious, and more tradition-bound, Federal Reserve. Quantitative easings critics want the Fed to be leaner and less activist. They want consumers to reduce their debts, not to borrow and spend anew, and they fear that quantitative easing will create a new consumption bubble. Bernanke, in fact, has been facile on this point; he told Congress in February, Our nations tax and spending policies should increase incentives to work and save, but his nearly zero percent interest rate clearly discourages saving.

...

Bernankes conception of the central bankers job, Blanchard pointed out, has been fuller, more comprehensive, than that of their fellow bankers in Europe. Indeed, the European Central Bank has lately begun to mimic the Feds approach to its own crisis. By mid-winter, U.S. unemployment had fallen to its lowest level since the end of the recession. Almost certainly, Bernanke will leave office with the United States in better shape than the Continent.

...

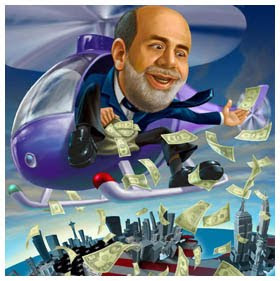

Originalists who are unhappy with quantitative easing are unhappy with elastic currency and with fiat money itself; nothing but gold will do. This has been true, of course, for 40 yearssince the U.S. went off the gold standardbut only Bernanke has had to implement with such vigor the Feds original missions of lender of last resort and coiner of an elastic currency. And he is up there now, in the helicopter, showering us with money, as the Fed didnt do but should have done in 1933. Yet even as this comforts, it elicits in most of us a spasm of wonder, or anxiety, that a single Ph.D. or a building full of them could calibrate such a mystery as the proper quantity of money, particularly in an economy as dynamic as ours is today. Bernanke does not use gold as a measuring stick; he does not count the money in circulation as a basis for determining interest rates, as Volcker did, or tried to do. His mentor, Milton Friedman, thought the business of adjusting interest rates was so tricky, it would be better to yield the job to a computer. But Bernanke thinks a human can do it. He sticks to his notion of what inflation should be, and his prediction of where it is headed, trusting that his judgment will tell him when to add more liquidity, when to subtract. And, to a greater extent than he is credited with now, history may marvel that Bernanke has been a success.

and get some radical lefty democrat the nomination followed by the win. Start a recession

and get some radical lefty democrat the nomination followed by the win. Start a recession