My point is that what does it mean by "time slowing"? When a car goes slower it goes fewer meters divided by how many seconds. What is divided by what to be able to say time is going slower?When we use atomic clocks, we can detect relativistic time differences with only 1 m of altitude difference, and the resulting different velocities. So the time slowing effect of our gravity well would be detectable as well with such a large magnitude.

This is part of the reason why you can write the horror story of watching the universe fall into heat death as you're falling into a black hole

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The thread for space cadets!

- Thread starter hobbsyoyo

- Start date

My point is that what does it mean by "time slowing"? When a car goes slower it goes fewer meters divided by how many seconds. What is divided by what to be able to say time is going slower?

The atomic clock will appear to run faster on the Moon from our perspective. Like, say we had a regular reporting system every time a 1 kg block of Cesium decayed 1% of its remaining radioactivity, the reports from the Moon would report faster decay than the one at our Earth location. But this is because we're in a deeper gravity well. Mars Clock would report the same signal from both clocks to Matt Damon.

But that is because they experience more time, not because the clocks are running faster.The atomic clock will appear to run faster on the Moon from our perspective. Like, say we had a regular reporting system every time a 1 kg block of Cesium decayed 1% of its remaining radioactivity, the reports from the Moon would report faster decay than the one at our Earth location. But this is because we're in a deeper gravity well. Mars Clock would report the same signal from both clocks to Matt Damon.

I actually don't know what your confusion is. "From our perspective". "As reported on Earth". The clocks would look like they're running faster.

Must be spectacular view.This is part of the reason why you can write the horror story of watching the universe fall into heat death as you're falling into a black hole

Though IIRC you won't have enough time to write anything as subjective time of falling would be quite short.

MrCynical

Deity

They have to put "not to scale", in case someone thought we would build giant clocks and obscure the face of the moon? Though I cannot get my head around the meaning of "clocks running faster"

I think this is a reference to relativistic time dilation. The deeper down a gravity well you are the more time is dilated, i.e. the slower a clock runs compared to one outside the gravity well. Since the moon's gravity well is much shallower than the earth's, a clock on the moon is experiencing a tiny bit less time dilation than an identical clock on earth, so will be running a tiny smidge faster.

The effect would be extremely small, but given the GPS system has to take relativity into account, presumably an equivalent system for the moon would also need to do so.

But that is because they experience more time, not because the clocks are running faster.

A clock is simply a process that happens at a known speed. If a clock experiences twice as much time as an observer, by dilation or whatever, then from the observer's perspective that clock is running twice as fast. I'm no expert on relativity, but as I understand it, the only distinction here would be semantics, not physics.

Last edited:

Broken_Erika

Play with me.

Nuclear powered rockets could take us to Mars, but will the public accept them?

Bob McDonald's blog: NASA and DARPA are beginning development of a new fission rocket

NASA has signed an agreement with the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop a nuclear rocket that could shorten travel time to Mars by about one quarter compared to traditional chemical rockets. But before nuclear technology is launched into space, there are risks that need to be addressed to ensure public safety.Nuclear rockets are not a new idea. Experiments were conducted in the 1950s by the U.S. military and later NASA but never put into space. Now, with the prospect of sending humans to Mars in the 2030s, the idea is being revived in an effort to shorten the roughly seven months it takes a conventional rocket to get to Mars. This might be a boon for future astronauts who face a seven-month, one-way journey using current technology.

The idea is to use a small fission reactor to heat up a liquid fuel to very high temperatures, turning it into a hot gas that would shoot out a rocket nozzle at high velocity, providing thrust.

The design of a nuclear rocket means they typically would produce less thrust than a chemical rocket, but nuclear engines could run continuously for weeks, constantly accelerating, ultimately reaching higher velocities in a tortoise-and-hare kind of way.

Nuclear propulsion is expected to be twice as fuel-efficient as chemical rockets, largely because they can heat the gas they use for thrust to a higher temperature than chemical combustion, and hotter gas means more energy.

A quicker trip to Mars provides huge benefits. Astronauts would be exposed to less cosmic radiation during the journey. The psychological pressures of living in a confined space far from home would be reduced. Supplies and a rescue mission could be delivered more quickly. These rockets could also open up the outer solar system so trips to Jupiter and its large family of icy moons could eventually be within reach.

While the technology of nuclear propulsion is certainly feasible, it may not be readily embraced by the public. The accidents at Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and Fukushima have left many people skeptical about nuclear safety. And there will be risk.

A nuclear rocket wouldn't be used to launch a spacecraft from the Earth's surface — it would be designed to run in space only. It would have to launch into orbit on a large chemical rocket — so the public would have to accept the risk of launching a nuclear reactor on a standard rocket filled with explosive fuel.

And rockets have and will malfunction catastrophically, in what with black humour rocket scientists sometimes call RUD — "rapid unscheduled disassembly."

No one wants to see nuclear debris raining down on the Florida coast or Disneyland, and that's not the only possible scenario. An accident in orbit could potentially drop radioactive material into the atmosphere.

These safety concerns need to be addressed before any nuclear rocket leaves the ground.

We've used nuclear, just not a reactor

Nuclear technology in another form has been used since the very beginning of the space program, just not for propulsion. Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) have provided power to deep space probes for instruments, radios and cameras on a range of missions.They're particularly useful for missions into deep space, like Voyager, Cassini and New Horizons which ventured too far from the sun for solar panels to be effective. They are also powering two rovers currently driving around on Mars: Perseverance and Curiosity.

RTGs are much simpler and lower-powered devices — and, crucially, are not nuclear reactors. Instead they convert the heat generated by the radioactive decay of a small amount of nuclear material (often plutonium) into electricity. These devices can run for decades. They twin Voyager spacecraft are still powered by RTGs that were launched in 1977 and are now outside our solar system.

Though there have been objections to their use since the 1980s, RTGs have proven relatively safe. The U.S. has seen several accidents, including one in 1968 when a launch failure of a Nimbus-1 weather satellite threw its RTG into the ocean. It was recovered intact and the fuel was reused on a later mission.

But there have been more serious accidents. Canadians may remember an incident from 1978, when a Soviet reconnaissance satellite scattered 50 kg of uranium from its nuclear thermal generator over 124,000 square kilometres of Canada's North.

But a fission reactor is a much more complicated device involving higher temperatures, coolants and more nuclear fuel.

Nuclear rockets hold great potential for the next generation of spacecraft that could enable humans to explore deeper into space.

However, the engineers face a challenge to ensure that all checks and balances have been made to reassure the astronauts who will fly these machines — and people on the ground — that they can be operated safely before the technology is adopted.

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/quirks/nuc...ars-but-will-the-public-accept-them-1.6727217

But that is because they experience more time, not because the clocks are running faster.

Yes, that is the physical reason. But the debate is about definition. If you are on the moon and ask "what time is it?", what should be the answer? You could base the answer on earth time, so the answer could be a time in UTC and expect the answer to be the same as if the answer was asked on earth. But then a clock on the moon would be running to fast relative to the time standard you chose.

Or you could introduce a moon time, according to the definition of a second and your clocks would be accurate. But this moon time would deviate from earth time in some way. It would either need regular, moon-only leap (micro-) seconds, or it would get an ever increasing offset to earth time.

Broken_Erika

Play with me.

Jupiter now has 92 moons — more than any other planet in our solar system

Giant planet breaks Saturn's record after astronomers spot 12 new moons in orbit

Astronomers have discovered 12 new moons around Jupiter, putting the total count at a record-breaking 92. That's more than any other planet in our solar system.Saturn, the one-time leader, comes in a close second with 83 confirmed moons.

The Jupiter moons were added recently to a list kept by the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center, said Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution, who was part of the team.

They were discovered using telescopes in Hawaii and Chile in 2021 and 2022, and their orbits were confirmed with follow-up observations. These newest moons range in size from 1 kilometre to 3 kilometres, according to Sheppard.

"I hope we can image one of these outer moons close-up in the near future to better determine their origins," he said in an email Friday.

In April, the European Space Agency is sending a spacecraft to Jupiter to study the planet and some of its biggest, icy moons. And next year, NASA will launch the Europa Clipper to explore Jupiter's moon of the same name, which could harbour an ocean beneath its frozen crust.

Sheppard — who discovered a slew of moons around Saturn a few years ago and has taken part in 70 moon discoveries so far around Jupiter — expects to keep adding to the lunar tally of both gas giants.

Jupiter and Saturn are loaded with small moons, believed to be fragments of once bigger moons that collided with one another or with comets or asteroids, Sheppard said.

- NASA's Juno spacecraft makes closest flyby in more than 20 years of Jupiter's moon Europa

- Goodbye, dark sky. The stars are rapidly disappearing from our night sky

Jupiter's newly discovered moons have yet to be named. Sheppard said only half of them are big enough — at least 1.5 kilometres or so — to warrant a name.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/space-jupiter-most-moons-1.6737087

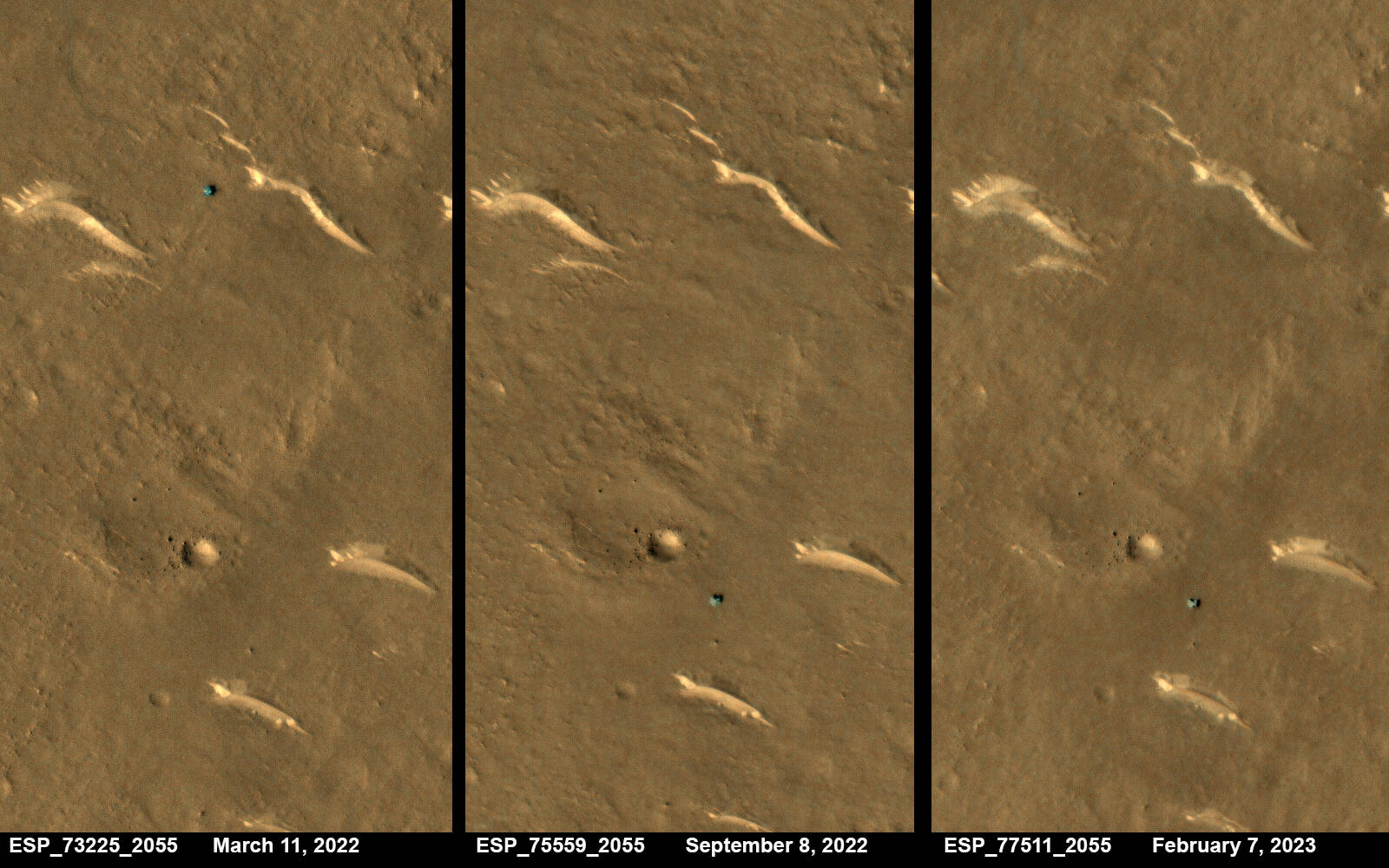

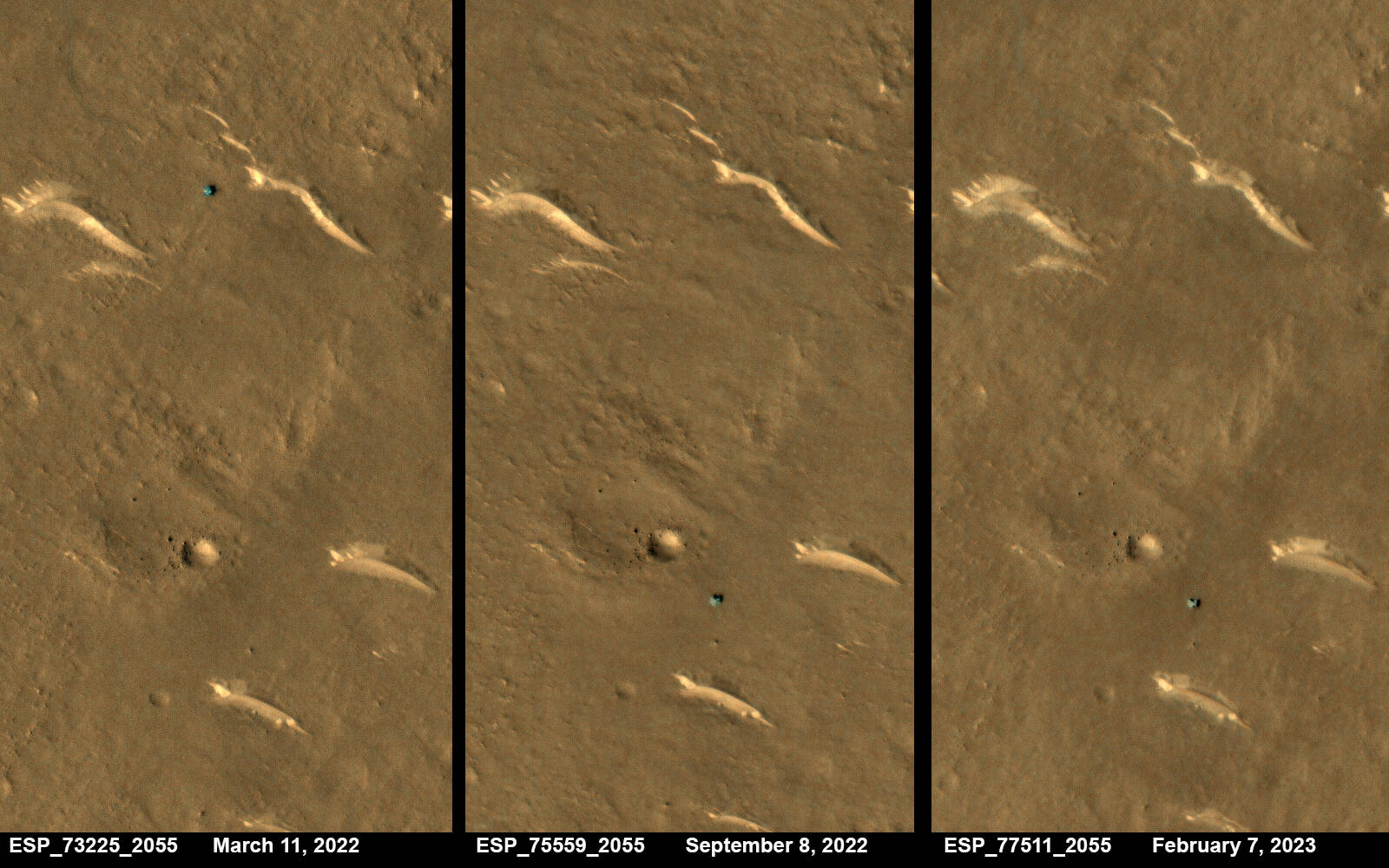

China's Zhurong rover may be dead: NASA images show no sign of life

Or maybe it's just resting and pining for the fjords

The Chinese Zhurong rover has been on Mars since May 2021, and HiRISE has imaged the region of Mars several times to monitor the surface for changes.

HiRISE is often used to observe changes to dust-covered areas near Mars surface missions. The blast zones around landings or tracks left by rovers can help scientists infer what the properties of surface materials are like.

This cutout is from three images acquired in 2022 and 2023. The rover is the dark and relatively bluish feature visible in the upper middle of the first (left) image and lower middle of the other two images. This time series shows that the rover has not changed its position between 8 September 2022 and 7 February 2023.

Or maybe it's just resting and pining for the fjords

The Chinese Zhurong rover has been on Mars since May 2021, and HiRISE has imaged the region of Mars several times to monitor the surface for changes.

HiRISE is often used to observe changes to dust-covered areas near Mars surface missions. The blast zones around landings or tracks left by rovers can help scientists infer what the properties of surface materials are like.

This cutout is from three images acquired in 2022 and 2023. The rover is the dark and relatively bluish feature visible in the upper middle of the first (left) image and lower middle of the other two images. This time series shows that the rover has not changed its position between 8 September 2022 and 7 February 2023.

Last edited:

Thorgalaeg

Deity

Ksp2 has been launched and it is terrible. Logically a game about disastrous launches had to be a disaster at launch.

India tests reusable spaceship

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on Sunday successfully flew and landed an autonomous reusable spaceplane.

The agency hoisted the Reusable Launch Vehicle Autonomous Landing Mission (RLV LEX) to an altitude of 4.5km beneath a helicopter, then watched as it navigated a steep approach to land 4.6km downrange.

The vehicle is designed to launch atop a rocket, enter orbit, deploy payloads, then return to Earth and land on a runway.

Readers will not be surprised to learn that the craft looks a lot like the US's retired Space Shuttle, and Russia's Buran reusable vehicle.

RLV LEX is, however, purely experimental at this stage and is yet to reach orbit. A 2016 test saw the vehicle released at an altitude of 65km and successfully demonstrate hypersonic flight capabilities. The Sunday test did not achieve similar speeds but did manage a hot landing at 350km/h.

ISRO hopes the vehicle one day makes it possible to launch payloads to orbit for just $4,000/kg – well below the cost of competing launch services.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on Sunday successfully flew and landed an autonomous reusable spaceplane.

The agency hoisted the Reusable Launch Vehicle Autonomous Landing Mission (RLV LEX) to an altitude of 4.5km beneath a helicopter, then watched as it navigated a steep approach to land 4.6km downrange.

The vehicle is designed to launch atop a rocket, enter orbit, deploy payloads, then return to Earth and land on a runway.

Readers will not be surprised to learn that the craft looks a lot like the US's retired Space Shuttle, and Russia's Buran reusable vehicle.

RLV LEX is, however, purely experimental at this stage and is yet to reach orbit. A 2016 test saw the vehicle released at an altitude of 65km and successfully demonstrate hypersonic flight capabilities. The Sunday test did not achieve similar speeds but did manage a hot landing at 350km/h.

ISRO hopes the vehicle one day makes it possible to launch payloads to orbit for just $4,000/kg – well below the cost of competing launch services.

r16

not deity

- Joined

- Nov 10, 2008

- Messages

- 12,375

was going to rant how journalists know nothing about anything but it came to me that it would have been a somewhat pointless exercise . To say it is an X-37 analogue would have resulted in a lot of angry letters to the editor , half of it quite justified in view of the prevalent racism in the world , considering like we are quite lighter skinned than the Indian stereotypes and stuff that happens to us . But everybody would understand how it works when the Rockwell Shuttle or Russian Buran were to be mentioned .

stfoskey12

Emperor of Foskania

NASA announced the crew of astronauts they hope to launch around the Moon with the Artemis 2 mission.

https://www.space.com/nasa-names-artemis-2-moon-crew

https://www.space.com/nasa-names-artemis-2-moon-crew

HOUSTON — NASA has named its first astronaut crew bound for the moon in more than 50 years.

The space agency on Monday (April 3) announced the four astronauts who will launch on its Artemis 2 mission (opens in new tab) to fly around the moon. The crew is expected to become the first moon voyagers since the Apollo program.

The Artemis 2 crew includes commander Reid Wiseman, pilot Victor Glover and mission specialists Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen. Hansen is a Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut flying under an agreement between the U.S. and Canada. He will be the first non-American to leave Earth orbit and fly to the moon.

GreatLordofPie

Prince

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2009

- Messages

- 386

HUBBLE SEES POSSIBLE RUNAWAY BLACK HOLE CREATING A TRAIL OF STARS

Broken_Erika

Play with me.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 779

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 2K