amadeus

rad thibodeaux-xs

Yay. I like food. A lot, most, is produced thanks to our modern industrial beast. Hail the Beast!The fact is modern angst and despair is painful but we're dependent on the modern industrial beast for our survival.

Yay. I like food. A lot, most, is produced thanks to our modern industrial beast. Hail the Beast!The fact is modern angst and despair is painful but we're dependent on the modern industrial beast for our survival.

Food industry likes you tooYay. I like food.

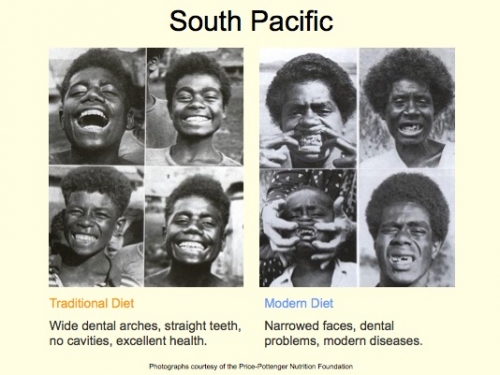

God bless bad teeth, obesity and diabetes. Agri to pharma to mortuary pipelineA lot, most, is produced thanks to our modern industrial beast. Hail the Beast!

This is incredibly funny because the health service in the UK basically tells you to get lost if you're fat. So "pharma" ain't doing much thereGod bless bad teeth, obesity and diabetes. Agri to pharma to mortuary pipeline

yeah we can go back to the preindustrial age when nobody got sick and everyone had great teethGod bless bad teeth, obesity and diabetes. Agri to pharma to mortuary pipeline

Usual lack of nuance as per my expectations.yeah we can go back to the preindustrial age when nobody got sick and everyone had great teeth

Free enterprise is a beautiful thing but when the playing field is tilted it hurts everyone but the very top, leading to some economic growth but low morale, rising inequality & an ever more dependent population.

(congratulations! you are not on my ignore list!)

![Party [party] [party]](/images/smilies/partytime.gif)

A book review that seems relevant:

The great rewiring: is social media really behind an epidemic of teenage mental illness?

The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness Jonathan Haidt Allen Lane (2024)

Two things need to be said after reading The Anxious Generation. First, this book is going to sell a lot of copies, because Jonathan Haidt is telling a scary story about children’s development that many parents are primed to believe. Second, the book’s repeated suggestion that digital technologies are rewiring our children’s brains and causing an epidemic of mental illness is not supported by science. Worse, the bold proposal that social media is to blame might distract us from effectively responding to the real causes of the current mental-health crisis in young people.

Spoiler Rest of article :Haidt asserts that the great rewiring of children’s brains has taken place by “designing a firehose of addictive content that entered through kids’ eyes and ears”. And that “by displacing physical play and in-person socializing, these companies have rewired childhood and changed human development on an almost unimaginable scale”. Such serious claims require serious evidence.

Haidt supplies graphs throughout the book showing that digital-technology use and adolescent mental-health problems are rising together. On the first day of the graduate statistics class I teach, I draw similar lines on a board that seem to connect two disparate phenomena, and ask the students what they think is happening. Within minutes, the students usually begin telling elaborate stories about how the two phenomena are related, even describing how one could cause the other. The plots presented throughout this book will be useful in teaching my students the fundamentals of causal inference, and how to avoid making up stories by simply looking at trend lines.

Hundreds of researchers, myself included, have searched for the kind of large effects suggested by Haidt. Our efforts have produced a mix of no, small and mixed associations. Most data are correlative. When associations over time are found, they suggest not that social-media use predicts or causes depression, but that young people who already have mental-health problems use such platforms more often or in different ways from their healthy peers1.

These are not just our data or my opinion. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews converge on the same message2–5. An analysis done in 72 countries shows no consistent or measurable associations between well-being and the roll-out of social media globally6. Moreover, findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, the largest long-term study of adolescent brain development in the United States, has found no evidence of drastic changes associated with digital-technology use7. Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University, is a gifted storyteller, but his tale is currently one searching for evidence.

Of course, our current understanding is incomplete, and more research is always needed. As a psychologist who has studied children’s and adolescents’ mental health for the past 20 years and tracked their well-being and digital-technology use, I appreciate the frustration and desire for simple answers. As a parent of adolescents, I would also like to identify a simple source for the sadness and pain that this generation is reporting.

A complex problem

There are, unfortunately, no simple answers. The onset and development of mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are driven by a complex set of genetic and environmental factors. Suicide rates among people in most age groups have been increasing steadily for the past 20 years in the United States. Researchers cite access to guns, exposure to violence, structural discrimination and racism, sexism and sexual abuse, the opioid epidemic, economic hardship and social isolation as leading contributors.

The current generation of adolescents was raised in the aftermath of the great recession of 2008. Haidt suggests that the resulting deprivation cannot be a factor, because unemployment has gone down. But analyses of the differential impacts of economic shocks have shown that families in the bottom 20% of the income distribution continue to experience harm9. In the United States, close to one in six children live below the poverty line while also growing up at the time of an opioid crisis, school shootings and increasing unrest because of racial and sexual discrimination and violence.

The good news is that more young people are talking openly about their symptoms and mental-health struggles than ever before. The bad news is that insufficient services are available to address their needs. In the United States, there is, on average, one school psychologist for every 1,119 students.

Haidt’s work on emotion, culture and morality has been influential; and, in fairness, he admits that he is no specialist in clinical psychology, child development or media studies. In previous books, he has used the analogy of an elephant and its rider to argue how our gut reactions (the elephant) can drag along our rational minds (the rider). Subsequent research has shown how easy it is to pick out evidence to support our initial gut reactions to an issue. That we should question assumptions that we think are true carefully is a lesson from Haidt’s own work. Everyone used to ‘know’ that the world was flat. The falsification of previous assumptions by testing them against data can prevent us from being the rider dragged along by the elephant.

A generation in crisis

Two things can be independently true about social media. First, that there is no evidence that using these platforms is rewiring children’s brains or driving an epidemic of mental illness. Second, that considerable reforms to these platforms are required, given how much time young people spend on them. Many of Haidt’s solutions for parents, adolescents, educators and big technology firms are reasonable, including stricter content-moderation policies and requiring companies to take user age into account when designing platforms and algorithms. Others, such as age-based restrictions and bans on mobile devices, are unlikely to be effective in practice — or worse, could backfire given what we know about adolescent behaviour.

A third truth is that we have a generation in crisis and in desperate need of the best of what science and evidence-based solutions can offer. Unfortunately, our time is being spent telling stories that are unsupported by research and that do little to support young people who need, and deserve, more.

Speaking of research and evidence what evidence is there that increased access to mental health services universally improves outcomes?The good news is that more young people are talking openly about their symptoms and mental-health struggles than ever before. The bad news is that insufficient services are available to address their needs. In the United States, there is, on average, one school psychologist for every 1,119 students.

Can't seem to access the study, first reference link doesn't work & final link is truncatedIs the Internet bad for you? Huge study reveals surprise effect on well-being

A global, 16-year study of 2.4 million people has found that Internet use might boost measures of well-being, such as life satisfaction and sense of purpose — challenging the commonly held idea that Internet use has negative effects on people’s welfare.

“It’s an important piece of the puzzle on digital-media use and mental health,” says psychologist Markus Appel at the University of Würzburg in Germany. “If social media and Internet and mobile-phone use is really such a devastating force in our society, we should see it on this bird’s-eye view [study] — but we don’t.” Such concerns are typically related to behaviours linked to social-media use, such as cyberbullying, social-media addiction and body-image issues. But the best studies have so far shown small negative effects, if any, of Internet use on well-being, says Appel.

The authors of the latest study, published on 13 May in Technology, Mind and Behaviour, sought to capture a more global picture of the Internet’s effects than did previous research. “While the Internet is global, the study of it is not,” said Andrew Przybylski, a researcher at the University of Oxford, UK, who studies how technology affects well-being, in a press briefing on 9 May. “More than 90% of data sets come from a handful of English-speaking countries” that are mostly in the global north, he said. Previous studies have also focused on young people, he added.

To address this research gap, Pryzbylski and his colleagues analysed data on how Internet access was related to eight measures of well-being from the Gallup World Poll, conducted by analytics company Gallup, based in Washington DC. The data were collected annually from 2006 to 2021 from 1,000 people, aged 15 and above, in 168 countries, through phone or in-person interviews. The researchers controlled for factors that might affect Internet use and welfare, including income level, employment status, education level and health problems.

Like a walk in nature

The team found that, on average, people who had access to the Internet scored 8% higher on measures of life satisfaction, positive experiences and contentment with their social life, compared with people who lacked web access. Online activities can help people to learn new things and make friends, and this could contribute to the beneficial effects, suggests Appel.

However, women aged 15–24 who reported having used the Internet in the past week were, on average, less happy with the place they live, compared with people who didn’t use the web. This could be because people who do not feel welcome in their community spend more time online, said Przybylski. Further studies are needed to determine whether links between Internet use and well-being are causal or merely associations, he added.

The study comes at a time of discussion around the regulation of Internet and social-media use, especially among young people. “The study cannot contribute to the recent debate on whether or not social-media use is harmful, or whether or not smartphones should be banned at schools,” because the study was not designed to answer these questions, says Tobias Dienlin, who studies how social media affects well-being at the University of Vienna. “Different channels and uses of the Internet have vastly different effects on well-being outcomes,” he says.

typically related to behaviours linked to social-media use, such

as cyberbullying, social-media addiction and body-image issues.

However, women aged 15–24 who reported having used the Internet in the past week were,

on average, less happy with the place they live, compared with people who didn’t use the web.

This could be because people who do not feel welcome in their community spend more time online, ...

I am not sure how the links are failing so much. This is the paper, but the DOI on that page failsCan't seem to access the study, first reference link doesn't work & final link is truncated

It seems there is a significant percentage who do not.I find this odd, as I doubt that there are enough women aged 15-24 in the west

who have not used the internet in the past week to be statistically significant.